Angélica Martínez-Bernal a, Beatriz Vasquez-Velasco a, Elia Ramírez-Arriaga b, *, María del Rocío Zárate-Hernández a, Enrique Martínez-Hernández b, Oswaldo Téllez-Valdés c

a Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa, División de Ciencias Biológicas y de la Salud, Av. San Rafael Atlixco Núm. 186, Iztapalapa, 09340 Ciudad de México, Mexico

b Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Geología, Ciudad Universitaria, Av. Universidad 3000, Coyoacán, 04510 Ciudad de México, Mexico

c Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala, Av. de Los Barrios 1, Los Reyes Iztacala, 54090 Tlanepantla de Baz, Estado de México, Mexico

*Corresponding author: elia@unam.mx (E. Ramírez-Arriaga)

Received: 14 August 2020; accepted: 16 November 2020

Abstract

An analysis of the floristic composition, structure and diversity of the tree and shrub strata was carried out at the tropical deciduous forest of El Picante hill, located in San José Tilapa, Puebla. Five transects (T1-T5) were located along the elevation range of 1,055 to 1,095 m asl and the “point-centred quarter” sampling method was used. A total of 53 taxa belonging to 47 genera and 28 families were recorded. The best-represented families were Fabaceae, Cactaceae, Asteraceae and Burseraceae. The main indicators in the tropical deciduous forest were those taxa with the highest importance value indexes (IVI), in the tree stratum were Ceiba aesculifolia, Bursera morelensis and B. aptera, while in the shrub stratum were Lippia graveolens, Parthenium fruticosum and Acaciella angustissima. T4 recorded the highest richness, on the other hand, T5 stood out by the presence of the greatest abundance of trees and shrubs. This study complements the structure and diversity knowledge of this ecosystem in Tehuacán Valley, México.

Keywords: Floristic composition; Tropical dry deciduous forest; Vertical and horizontal structure; Semiarid ecosystem; Tehuacán Valley

Composición, estructura y diversidad de los estratos arbóreo y arbustivo en un bosque tropical caducifolio en el valle de Tehuacán, México

Resumen

Se llevó a cabo un análisis de la composición florística, estructura y diversidad de los estratos arbóreo y arbustivo en el bosque tropical caducifolio del cerro El Picante, ubicado en San José Tilapa, Puebla. Se estudiaron 5 transectos (T1-T5) a lo largo de un rango de elevación de 1,055 a 1,095 m snm y se utilizó el método de muestreo de cuadrantes centrados en un punto. Un total de 53 taxones pertenecientes a 47 géneros y 28 familias fueron registrados. Las familias mejor representadas fueron Fabaceae, Cactaceae, Asteraceae y Burseraceae. Los taxones con el mayor índice de valor de importancia (IVI) en el estrato arbóreo fueron Ceiba aesculifolia, Bursera morelensis y B. aptera, mientras que en el estrato arbustivo fueron Lippia graveolens, Parthenium. fruticosum y Acaciella angustissima. El transecto T4 registró la mayor riqueza y en T5 se cuantificó la mayor abundancia de árboles y arbustos. Este estudio complementa el conocimiento sobre la estructura y diversidad este ecosistema en el valle de Tehuacán, México.

Palabras clave: Composición florística; Selva baja caducifolia; Estructura vertical y horizontal; Ecosistema semiárido; Valle de Tehuacán

© 2021 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. Este es un artículo Open Access bajo la licencia CC BY-NC-ND

Introduction

The tropical deciduous forest (TDF) occurs in 25 of the 32 Mexican states. It represents 80% of the vegetation cover on the Pacific slope, part of central Mexico, the Balsas Depression and the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Valley. Besides, the remaining 20% of the TDF occurs on the slope of the Gulf of Mexico (Banda et al., 2016; Challenger & Soberón, 2008; Dirzo, 1994; Meave et al., 2012; Miranda & Hernández, 1963; Pennington & Sarukhán, 2005; Rzedowski, 1978; Rzedowski & Calderón-de Rzedowski, 1987, 2013; Trejo, 1998, 1999).

Research related to the dynamics, functioning and ecology of TDFs has allowed us to generate knowledge about this plant community, which grows on mountains, hillsides and gradients with moderate to strong slopes (Challenger & Soberón, 2008; Rzedowski, 1978; Trejo, 1996, 2010). Climate is mainly warm subhumid (Awo) according to the Köppen classification, modified by García (2004). The Burseraceae and Fabaceae families are well-represented in the TDF, along with Anacardiaceae, Cactaceae, Asteraceae, Euphorbiaceae, Malpighiaceae and Rubiaceae, among others (Miranda & Hernández, 1963; Rzedowski, 1978; Trejo, 1996, 2005, 2010).

A total of 749 genera and 2,500 species have been recorded, included in the primary and secondary vegetation of this ecosystem. The distinctive feature of the TDF is its marked seasonality reflected in the phenology of the plants, with the presence of a long dry season lasting 3 to 8 months (over 75%), while the rainy season lasts 4 to 6 months. The physiognomy of the TDF is characterised by trees that vary in height from 8 to 12 m on average (Banda et al., 2016; Challenger & Soberón, 2008; Miranda & Hernández, 1963; Pennington & Sarukhán, 2005; Rzedowski, 1978; Rzedowski & Calderón-de Rzedowski, 2013; Trejo, 1996, 2005, 2010).

It should be noted that in the last 2 decades, there has been an increasing number of regional- or state-level studies on the functioning of the TDF in the context of physiognomy, structure, floristic composition and diversity. Some notable studies, grouped by their geographical distribution, are as follows: 1) Pacific Slope: in Sonora (Sánchez-Mejía et al., 2007); Banderas Bay, Nayarit (Bravo-Bolaños et al., 2016); Baja California Peninsula (León-de la Luz et al., 2012); Oaxaca (Gallardo-Cruz et al., 2005) and the Central Depression of Chiapas (Rocha-Loredo et al., 2010); 2) Central Mexico: at the Balsas Depression (Méndez-Toribio et al., 2014; Pineda-García et al., 2007); Puebla (Rodríguez-Acosta et al., 2014); Sierra de Huautla Biosphere Reserve, Morelos (Beltrán-Rodríguez et al., 2018) and 3) Gulf Slope: at the Dzilam Reserve, Yucatán (Leirana-Alcocer et al., 2009), Campeche (Dzib-Castillo et al., 2014), and Veracruz (Williams-Linera & Lorea, 2009).

The analysis of the area and percentage of the tropical deciduous forest (TDF) in the country shows a clear decrease in its distribution area. The first estimate was calculated at 31,521,290 ha (15.98%) by Flores et al. (1971). Other reports are those of Rzedowski and Calderón-de Rzedowski (2013) with 28,000,000 ha (14%); INEGI (1980) with 15,980,000 ha (8.2%); Trejo (2010) ca. 6,850,000 ha (30%); Conafor-Semarnat (2012) with 12% (15,869,741.80 ha). Trejo and Dirzo (2000) reported that 3.7% (72,900 km2) corresponds to primary vegetation. Finally, the data provided by INEGI (2003) is 33.5 million hectares, while Challenger and Soberón (2008) reported an estimate of 11.26% (7.93 and 14.19 million hectares as primary and secondary vegetation, respectively) of the surface area of the entire Mexican territory. Recently, INEGI (2014) reported that the TDF occupies 11.9% of Mexico’s vegetation cover.

Among the processes that have impacted the functioning and fragility of this ecosystem are exploitation of forest resources, land-use changes, habitat fragmentation, introduction of exotic species, forest fires, urban, industrial and tourism development and communication routes, among others (Dirzo et al., 2011; Hansen et al., 2013; Maass et al., 2010; Ramírez-Bravo & Hernández-Santin, 2016; Rzedowski, 1978; Rzedowski & Calderón-de Rzedowski, 2013). It is also important to highlight the limited resilience of the secondary community of the TDF compared to a climax community (Rzedowski & Calderón-de Rzedowski, 2013). Therefore, it is considered the most threatened tropical ecosystem worldwide (Banda et al., 2016; Beltrán-Rodríguez et al., 2018; Ceballos & García, 1995; Janzen, 1988; Masera et al., 1997; Miles et al., 2006; Trejo, 2005; Trejo & Dirzo, 2000).

In the state of Puebla, TDF occupies 15.7% (536,851 ha) (Rodríguez-Acosta et al., 2014) and represents 29% of the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Valley area, where there are also various types of vegetation and a high levels of endemism, including TDF (Arriaga et al., 2000; Dávila et al., 1993, 2002; Osorio Beristain et al., 1996). Previous studies have been conducted in this region throughout the past seventy years, including floristic and phytogeographic ones (Jaramillo-Luque & González-Medrano, 1983; Miranda, 1948; Smith, 1965; Valiente-Banuet et al., 2000, 2009; Villaseñor et al., 1990; Zavala-Hurtado, 1982).

The objective of this study was to determine, the structure, diversity and floristic composition of the tree and shrub strata in the tropical deciduous forest of El Picante hill, located in the town of San José Tilapa, Puebla, in the south-eastern Tehuacán Valley, Mexico. This knowledge will not only complement the understanding of the dynamics and functioning of this ecosystem in relation to other regions of Mexico, but it will also be useful for decision-making regarding its conservation.

Material and methods

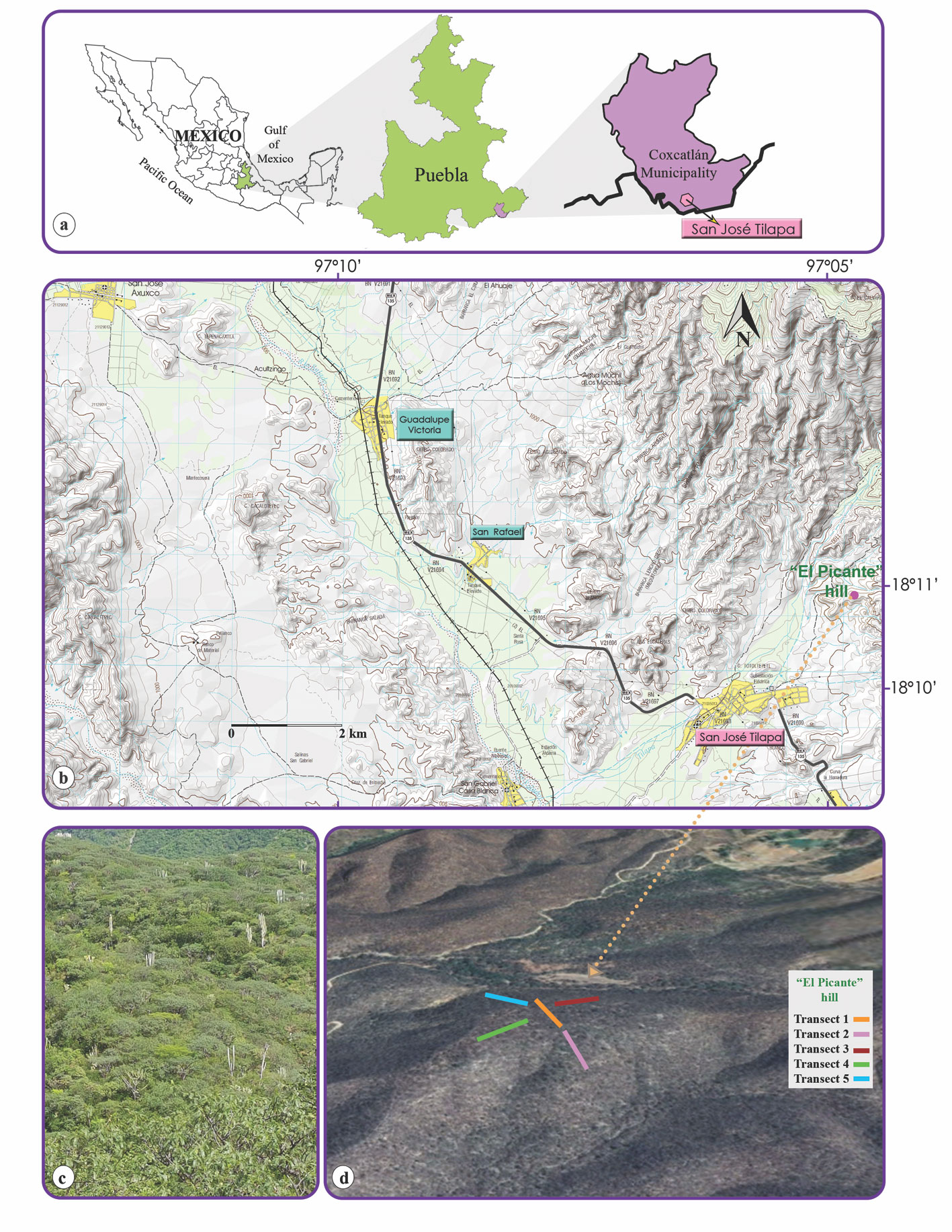

The study was conducted in the tropical deciduous forest (TDF) of El Picante hill, located 3 km northwest of the dirt road to San Antonio Barranca Vigas, between coordinates 18°10’49” and 18°10’59” N, 97°04’44.8” and 97°04’50.9” W, with an altitude range between 1,033 and 1,099 m asl, in the town of San José Tilapa, municipality of Coxcatlán, Puebla, Mexico, in the south-eastern Tehuacán Valley (Fig. 1a-d). The municipality of Coxcatlán is located in the province of the Sierra Madre del Sur, which includes the subprovinces of the eastern and central Sierras of Oaxaca. The temperature ranges from 14 to 26 °C, and the annual rainfall fluctuates from 300 to 1,100 mm. The climate can be very warm arid and warm arid (48% of surface area), semi-warm semi-arid (28%), temperate subhumid with summer rains (14%) and semi-warm sub-humid with summer rains (10%). The dominant soil type is Regosol, but Leptosol and Cambisol are also found. The types of vegetation present are tropical deciduous forest (32%), scrub (20%), forest (9%) and grasslands (3%) (Conabio, 2011; INEGI, 2009).

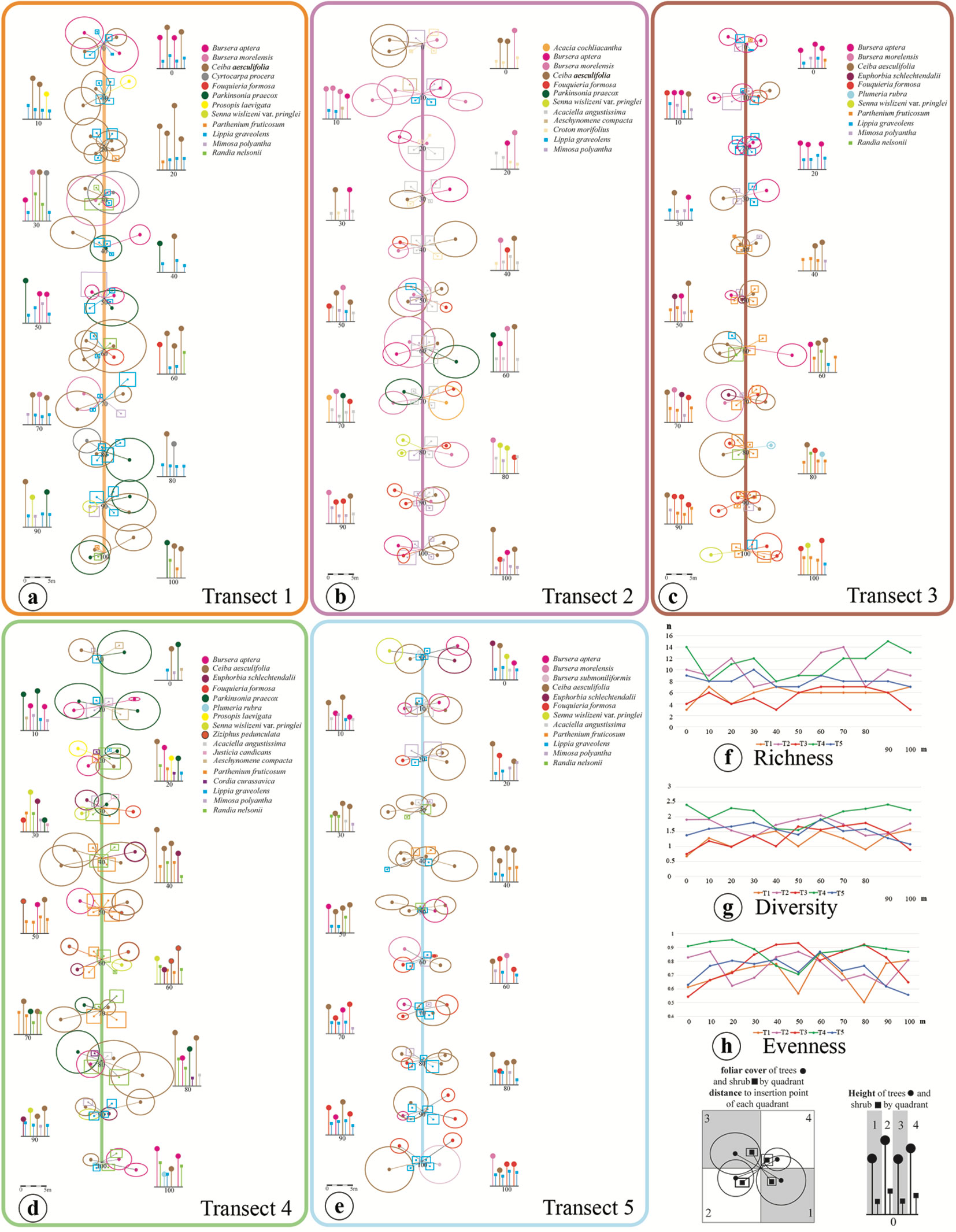

Trees and shrubs were recorded during an annual cycle. Botanical samples were collected for latter identification. Since transects and plots have generally been used for studies of TDF vegetation in Mexico (Dzib-Castillo et al., 2014; León-de la Luz et al., 2012; Méndez-Toribio et al., 2014; Pineda-García et al., 2007; Rocha-Loredo et al., 2010), in the present work, a total of 5 transects (100 m long each) were established in different positions; at the summit (T1), in the north-eastern (T3), north-western (T5), western (T4) and south-eastern (T2) slopes of the hill (Fig. 1d), following the “point-centred quarter” sampling method, according to Matteucci and Colma (1982) and Mueller-Dombois and Ellenberg (1974). According to the method all transects (T1-T5) were divided every 10 meters and a total of 11 points per transect were considered. At each division, 4 quadrats were formed by one imaginary line crossed perpendicularly. In each quadrant, a tree and a shrub closest to the central point were located and the distance of them to the central point was recorded. For each tree and shrub (8 in total) the following measurements were taken: height, small (c) and large (C) diameters of canopy cover. Also, diameter at breast height (DBH at 1.30 m) for trees was obtained (Matteucci & Colma, 1982). To others short trees, shrubs, arborescent and rosette plants only density was recorded.

In addition, geographical coordinates, elevation and slope were recorded for each of the 10 central points of the transects. Collection of botanical samples was performed as completely as possible, with flowers and/or fruits and their respective duplicates, which were dried and pressed according to the methods proposed by Lot and Chiang (1986) for subsequent taxonomic determination, mounting and labelling. It should be noted that the floristic inventory was extended because of additional botanical collection performed in the transects studied. Plant identification was performed using various taxonomic keys included in several regional floras and in specialised literature. Once identified, the specimens were mounted and registered for incorporation into the Herbario Metropolitano (UAMIZ) from the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa (UAM-I).

Vertical structure was analysed using the data from the height measurements of the trees and shrubs and the location of this vegetation in the strata. Tree strata were classified by height as follows: short: 2–4 m, medium: 4–6 m, and tall: ≥ 6 m. Shrub strata were similarly grouped: short: ≤ 1 m, medium: > 1-2 m, and tall: 2–4 m according to the González-Medrano (2003) classification. Horizontal structure was calculated using the following parameters: density, dominance and frequency, along with their respective relative values, in order to obtain the importance value index (IVI) of each of the species present at each sampling site. The following equations modified from Gaillard-de Benítez and Pece (2011) were used in order to calculate density.

For the calculation of the mean distance (D) of the trees and shrubs per hectare, the distances of each individual of each species from the central point were used; the sum of these distances was divided by the total number of individuals, as follows: the mean distance (D) of the trees and shrubs was calculated as follows:

(D): Σdi…n /N,

where: di = the distance from i species to the centre of the transect; N = the total number of individuals.

The mean distance (D) values obtained were used to calculate the total tree and shrub density per hectare (DenTha) as follows:

DenTha= 10000 m2 /D2

Schematic diagrams were made for each of the transects using Adobe Illustrator software.

Richness (N) along with the Shannon-Wiener diversity index (H’), Pielou’s evenness index (J’), and the Jaccard similarity index (Magurran, 1988, 2004) were calculated using Multi-Variate Statistical Package (MVSP) software v. 3.2.

Results

General floristic composition

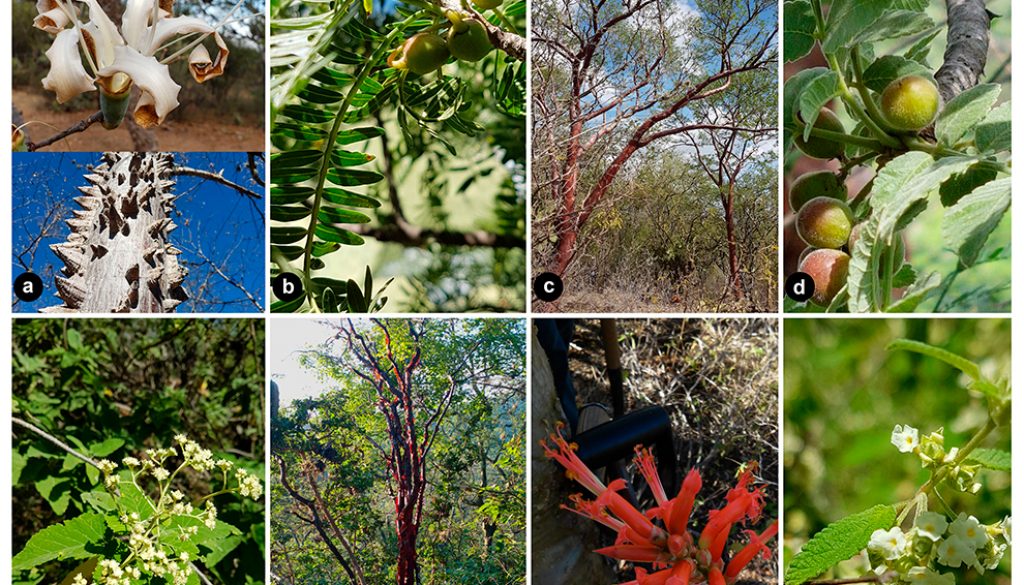

The plant composition of the tropical deciduous forest (TDF) on El Picante hill is made up of 53 taxa belonging to 47 genera and 28 families organized according to the APG III system (APG 2009; Table 1, Fig. 2). The Fabaceae family was the best represented with 10 taxa, contributing 18.9% of the flora, followed by Cactaceae (7.5%) with 4 taxa, Asteraceae (5.6%), and Burseraceae (5.6%), with 3 taxa each, followed by 9 families with 2 taxa each (Σ = 34%), and finally 15 families with a single taxon each (Σ = 28.3%). It is important to mention that 14 species endemic to the country were recorded in this study. They belong to 9 families: Cactaceae and Fabaceae were represented by 3 species each, Burseraceae with 2 species and 6 other families contributed 1 species each (Table 1).

Our survey showed that the abundance of life forms included 1,740 individuals (trees, shrubs, arborescent and rosette plants) recorded in the 220 quadrants of the 55 points marked in the 5 transects (Table 2).

Exclusively considering the trees (190 individuals) and the shrubs (210 individuals) in all transects (T1-T5), a total of 22 species was recorded. In addition, transects T4 on the W slope showed the highest richness values (Table 2). Although the total abundance values showed a slight variation, transect T5 on the NW slope exhibited the highest total abundance, followed by transects T2 and T4 (Table 2).

The floristic composition of the TDF on El Picante hill comprised the tree species Bursera aptera, B. morelensis, Ceiba aesculifolia, Fouquieria formosa and Senna wislizeni var. pringlei. With the exception of B. morelensis, which was recorded in T1-T3 and T5, all of the other 4 species occurred in all 5 studied transects (T1-T5). The shrub stratum was made up of Mimosa polyantha, Lippia graveolens, Randia nelsonii and Parthenium fruticosum (T1, T3, T4 and T5). The first 2 species listed occurred in all 5 transects. It is also important to note that there were species unique to 4 of the 5 transects, as follows: Cyrtocarpa procera (T1), Acacia cochliacantha (T2), Ziziphus pedunculata (T4) and Bursera submoniliformis (T5). Similarly, the shrub stratum included Croton morifolius (T2), Cordia curassavica and Justicia candicans (T4), as taxa that exclusively occurred in these transects.

Table 1

Floristic composition of the tropical deciduous forest (TDF) on El Picante hill in San José Tilapa, Puebla, Mexico. The inventory includes families, genera, species, common name and biological form. Species endemic to Mexico are indicated with an asterisk (*) and taxa for the analysis of vegetation structure are marked with a black dot (•) and in bold type.

| Families/species | Common name | Biological form |

| Acanthaceae

• Justicia candicans (Nees) L.D. Benson |

shrub | |

| ANACARDIACEAE

*• Cyrtocarpa procera Kunth |

“chupandillo” | tree |

| Apocynaceae

Asclepias curassavica L. • Plumeria rubra L. |

“flor de mayo” | suffrutex

tree |

| Asparagaceae

Agave sp. Echeandia sp. |

rosette

herb |

|

| Asteraceae

*• Parthenium fruticosum Less. Sanvitalia fruticosa Hemsl. Zinnia peruviana (L.) L. |

shrub

herb herb |

|

| Bignoniaceae

Astianthus viminalis Baill. |

tree | |

| Bromeliaceae

*Tillandsia circinnatioides Matuda Tillandsia recurvata (L.) L. |

epiphyte

epiphyte |

|

| Burseraceae

*• Bursera aptera Ramírez • Bursera morelensis Ramírez *• Bursera submoniliformis Engl. |

“cuajiote amarillo” | tree

tree tree |

| Cactaceae

*Coryphantha pallida Britton & Rose *Myrtillocactus geometrizans (Mart. ex Pfeiff.) Console Opuntia sp. *Pachycereus weberi (J.M.Coult.) Backeb. |

globular

columnar- branched arborescent columnar- branched |

|

| Capparaceae

Quadrella incana (Kunth) Iltis & Cornejo |

“mata gallina” | tree |

| Table 1. Continued | ||

| Families/species | Common name | Biological form |

| Commelinaceae

Commelina sp. Tradescantia sp. |

herb

herb |

|

| Convolvulaceae

Jacquemontia smithii B.L.Rob., & Greenm. |

shrub | |

| Cordiaceae

• Cordia curassavica (Jacq.) Roem., & Schult. Cordia stellata Greenm. |

shrub

shrub |

|

| Ehretiaceae

Bourreria obovata Eastw. |

shrub | |

| Euphorbiaceae

• Croton morifolius Willd. • Euphorbia schlechtendalii Boiss. |

shrub

tree |

|

| Fouquieriaceae

*• Fouquieria formosa Kunth |

tree | |

| Fabaceae

• Acacia cochliacantha Humb., & Bonpl. ex Willd. • Acaciella angustissima var. filicioides (Cav.) L.Rico • Aeschynomene compacta Rose * Mimosa brevispicata Britton * Mimosa luisana Brandegee *• Mimosa polyantha Benth. • Parkinsonia praecox (Ruiz & Pav. ex. Hook.) Hawkins • Prosopis laevigata (Humb., & Bonpl. ex Willd.) M.C.Johnst. • Senna wislizeni var. pringlei (Rose) H.S.Irwin & Barneby Zapoteca formosa (Kunth) H.M.Hern. |

“uña de gato”

“mantecoso” “mezquite” “tecuahue” |

tree

shrub shrub shrub shrub shrub tree tree tree shrub |

| Heliotropiaceae

Heliotropium angiospermum Murray |

suffrutex | |

| Malpighiaceae

Calcicola parvifolia (A.Juss.) W.R.Anderson & C.Davis |

shrub | |

| Table 1. Continued | ||

| Families/species | Common name | Biological form |

| Malvaceae

• Ceiba aesculifolia (Kunth) Britten & Baker f. Melochia tomentosa L. |

“pochote” | tree

shrub |

| Onagraceae

Ludwigia octovalvis (Jacq.) P.H.Raven |

herb | |

| Polygonaceae

Podopterus mexicanus Bonpl. |

tree | |

| Rhamnaceae

*• Ziziphus pedunculata (Brandegee) Standl. |

“cholulo” | shrub |

| Rubiaceae

Hintonia latiflora (DC.) Bullock • Randia nelsonii Greenm. |

“zapotillo” | tree

shrub |

| Sapindaceae

Cardiospermum microcarpum Kunth |

liana | |

| Solanaceae

* Solanum tridynamum Dunal |

shrub | |

| Talinaceae

Talinum paniculatum (Jacq.) Gaertn. |

herb | |

| Verbenaceae

Lantana camara L. • Lippia graveolens Kunth |

“orégano” | shrub

shrub |

Estimating the vertical and horizontal structure

The analysis of the vegetation structure included 13 families, 20 genera and 22 species, all of them are marked with a symbol (•) in table 1. The vertical data showed that species with the highest number of individuals in the tree stratum were Ceiba aesculifolia, followed by Bursera aptera and Fouquieria formosa; with respect to height, the medium group was the best represented (Fig. 3a-e). The most abundant taxa in the shrub stratum were Lippia graveolens, followed by Parthenium fruticosum and Mimosa polyantha. Most shrubs exhibited medium height (Fig. 3a-e).

About the horizontal structure, the total tree density (DenTha) of transects T1 and T3 recorded the highest values, while the largest basal area was found in transect T1. The species that showed the highest density were Bursera aptera, B. morelensis, Ceiba aesculifolia, Fouquieria formosa and Parkinsonia praecox. These species also showed the most significant IVI values. C. aesculifolia and B. aptera were recorded in 4 transects, F. formosa in 3, P. praecox in 2 and B. morelensis was only recorded in 1 transect (Table 3). As for the total density of the shrubs (DenTha), transects T3 and T5 (Fig. 3c, e) recorded the highest values, while the highest cover value was found in transect T4 (Fig. 3d). The shrubs with the highest densities were Lippia graveolens, Acaciella angustisima, Mimosa polyantha, Randia nelsonii, Croton morifolius and Parthenium fruticosum. These same taxa showed the higher IVI values (Table 4).

In the TDF on El Picante hill, most of the trees exhibited a height in the range of 4 to 6 metres, placing them in the medium group. Both the short and the tall trees followed in importance. The shrub stratum showed dense canopy, more than 50% of the individuals were of medium height (Fig. 3b, c).

The analysis of the height and canopy cover data for the species present in the tree and shrub strata in the 5 transects (Fig. 3a-e) showed that Ceiba aesculifolia was the tallest tree (2.60-12.0 m) and it also exhibited the largest canopy cover (small canopy cover or c = 1.6-11.0; large canopy cover or C = 2.4-12.8 m). Randia nelsonii, present in transects T1, T3 and T4 (Fig. 3a, c, d), was the tallest shrub (0.9-7.0 m) and it also had the greatest canopy cover (c = 0.64-4.2; C = 0.7-4.3 m). Another species that is important to mention for transects T1, T3 and T5 (Fig. 3a, c, e) is Mimosa polyantha which exhibited high canopy cover values (c = 0.67-4.84; C = 0.7-5.05 m). Acaciella angustissima was significant in T2 (Fig. 3b) as it showed the greatest foliar cover (c = 0.65-6.7; C = 0.74-6.9 m).

Moreover, the results of this study allowed us to draw some interesting deductions; transects T1 (at the top of the hill) and T4 (to the western) exhibited the largest canopy cover, within the tree stratum highlighted B. morelensis, C. aesculifolia, C. procera and P. praecox, all of them were also the tallest trees. Meanwhile, in the shrub stratum M. polyantha, R. nelsonni and Z. pedunculata recorded the most important and the tallest shrubs. All transect showed very similar richness values of trees and shrubs with exception of T4 which recorded the highest richness value (Table 2, Fig. 3). On the other hand, T5 stood out by the presence of the greatest abundance of trees and shrubs (Table 2).

Table 2

Richness (N), total counts in bold type and abundances of trees and shrubs, in parentheses abundances of these biological forms near to the center point in the 5 transects (in bold types).

| Transects | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | Total |

| N trees | 8 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 7 | N = 13 |

| N shrubs | 4 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 5 | N = 9 |

| N arborescents | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | N = 4 |

| N rosettes | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | N = 4 |

| Total richness of trees and shrubs | 12 | 12 | 11 | 17 | 12 | N = 22 |

| Abundance of trees | 58

(37) |

73

(38) |

49

(34) |

75

(39) |

125

(42) |

380

(190) |

| Abundance of shrubs | 172

(40) |

329

(43) |

139

(44) |

243

(42) |

339

(41) |

1,222

(210) |

| Abundance of arborescents | 0 | 13 | 1 | 20 | 33 | 67 |

| Abundance of rosettes | 21 | 0 | 11 | 2 | 37 | 71 |

| Total abundance of trees and shrubs | 230

(77) |

402

(81) |

188

(78) |

318

(81) |

464

(83) |

1,602

(400) |

| Total abundance of all biological forms | 251 | 415 | 200 | 340 | 534 | 1,740 |

Ecological parameters

The highest diversity values were observed in T4 (Fig. 3d). The former transect recorded the highest number of species and it is where the abundance of organisms was most equitably distributed among the species, while the latter also showed a high richness value but not in terms of evenness (Fig. 3f, h).

The Jaccard index showed that transects T3 and T5 had the highest percentages of similarity (Table 5). The species shared between these transects were Bursera aptera, B. morelensis, Ceiba aesculifolia, Euphorbia schlechtendalii, Fouquieria formosa, Senna wislizeni var. pringlei, L. graveolens, Mimosa polyantha, Parthenium fruticosum, and Randia nelsonii. On the other hand, Plumeria rubra was exclusive to the transect T3, and both Acaciella angustissima and Bursera submoniliformis were unique to the transect T5.

Discussion

This study focused exclusively on tree and shrub strata in the TDF on El Picante hill in San José Tilapa (Coxcatlán), Puebla, within the Tehuacán Valley. Although collection was performed among the transects in order to supplement the floristic inventory, the total richness observed was low compared with those studies performed within plots (Table 6). However, it should be mentioned that in another research conducted in the same municipality of Coxcatlán, in the town of Calipan, Trejo (2005) whom did not explain the methods of sampling, also reported low species richness (29 spp.), which she justified by the study area proximity to other types of vegetation with an affinity towards xeric environments, such as xerophilous scrub (Table 6).

Table 3

Structural parameters of the species present in the tree stratum on the 5 transects in the TDF on El Picante hill, San José Tilapa, Mexico. Total density of individuals per hectare (DenTha), mean basal area (Ab), absolute density (DenA), relative density (DenR), absolute dominance (DomA), relative dominance (DomR), absolute frequency (FA), relative frequency (FR) and the importance value index (IVI). The 3 species with the highest IVI are indicated in bold type.

| N° | Species | DenTha | Ab | DenA | DenR | DomA | DomR | FA | FR | IVI

(%) |

| 1 | Ceiba aesculifolia

Parkinsonia praecox Bursera aptera Bursera morelensis Cyrtocarpa procera Prosopis laevigata Fouquieria formosa Senna wislizeni var. pringlei Total |

423.11

111.34 133.61 44.54 44.54 22.27 22.27 22.27 823.94 |

91.47

27.87 23.66 24.20 15.13 2.66 1.57 0.69 187.28 |

0.51

0.14 0.16 0.05 0.05 0.03 0.03 0.03 1 |

51.35

13.51 16.21 5.40 5.40 2.70 2.70 2.70 100 |

0.48

0.14 0.12 0.12 0.08 0.014 0.008 0.003 1 |

48.84

14.88 12.63 12.91 8.08 1.42 0.84 0.37 100 |

0.38

0.19 0.15 0.07 0.07 0.03 0.03 0.03 1 |

38.46

19.23 15.38 7.69 7.69 3.84 3.84 3.84 100 |

46.21

15.87 14.74 8.67 7.05 2.65 2.46 2.30 100 |

| 2 | Bursera morelensis

Ceiba aesculifolia Fouquieria formosa Bursera aptera Parkinsonia praecox Senna wislizeni var. pringlei Acacia cochliacantha Total |

150.04

136.4 95.48 68.2 27.28 27.28 13.64 518.32 |

50.08

22.62 1.95 9.86 9.82 0.49 0.56 95.40 |

0.28

0.26 0.18 0.13 0.05 0.05 0.02 1 |

28.94

26.31 18.42 13.15 5.26 5.26 2.63 100 |

0.52

0.23 0.02 0.103 0.102 0.005 0.0059 1 |

52.5

23.71 2.048 10.33 10.3 0.51 0.6 100 |

0.29

0.22 0.19 0.16 0.06 0.03 0.03 1 |

29.03

22.58 19.35 16.12 6.45 3.22 3.22 100 |

36.82

24.2 13.27 13.2 7.33 3.001 2.15 100 |

| 3 | Ceiba aesculifolia

Bursera aptera Fouquieria formosa Bursera morelensis Euphorbia schlechtendalii Plumeria rubra Senna wislizeni var. pringlei Total |

247.11

271.82 197.68 24.71 49.42 24.71 24.71 840.16 |

31.32

30.66 10.71 10.34 2.76 0.78 0.78 87.36 |

0.29

0.32 0.23 0.02 0.05 0.02 0.02 1 |

29.41

32.35 23.53 2.94 5.88 2.94 2.94 100 |

0.36

0.35 0.12 0.12 0.03 0.01 0.01 1 |

35.86

35.10 12.26 11.84 3.16 0.89 0.89 100 |

0.33

0.25 0.21 0.04 0.08 0.04 0.04 1 |

33.33

25 20.83 4.17 8.33 4.17 4.17 100 |

32.87

30.82 18.87 6.32 5.79 2.67 2.67 100 |

| 4 | Ceiba aesculifolia

Parkinsonia praecox Bursera aptera Euphorbia schlechtendalii Senna wislizeni var. pringlei Ziziphus pedunculata Fouquieria formosa Prosopis laevigata Plumeria rubra Total |

153.69

82.75 82.75 35.47 35.47 35.47 11.82 11.82 11.82 461.06 |

28.36

16.00 10.19 0.95 0.79 0.86 3.34 0.27 0.06 60.81 |

0.33

0.17 0.17 0.07 0.07 0.07 0.02 0.02 0.02 1 |

33.33

17.95 17.95 7.69 7.69 7.69 2.56 2.56 2.56 100 |

0.47

0.26 0.17 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.05 0.00 0.00 1 |

46.63

26.30 16.75 1.57 1.30 1.41 5.50 0.44 0.10 100 |

0.27

0.20 0.17 0.10 0.10 0.07 0.03 0.03 0.03 1 |

26.67

20.00 16.67 10.00 10.00 6.67 3.33 3.33 3.33 100 |

35.54

21.42 17.12 6.42 6.33 5.26 3.80 2.11 2.00 100 |

| 5 | Ceiba aesculifolia

Fouquieria formosa Bursera aptera Bursera submoniliformis Bursera morelensis Euphorbia schlechtendalii Senna wislizeni var. pringlei Total |

290.13

131.88 79.13 13.19 13.19 13.19 13.19 553.88 |

33.68

5.45 7.88 3.73 1.66 1.27 0.34 54.00 |

0.52

0.23 0.14 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.02 1 |

52.38

23.81 14.29 2.38 2.38 2.38 2.38 100 |

0.62

0.10 0.15 0.07 0.03 0.02 0.01 1 |

62.36

10.10 14.59 6.91 3.07 2.35 0.62 100 |

0.42

0.23 0.19 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 1 |

42.31

23.08 19.23 3.85 3.85 3.85 3.85 100 |

52.35

19.00 16.04 4.38 3.10 2.86 2.28 100 |

Table 4

Structural parameters of the species present in the shrub stratum, on the 5 transects in the TDF on El Picante hill, San José Tilapa, Mexico. Density of individuals per hectare (DenTha), mean foliar cover (Cob), absolute density (DenA), relative density (DenR), dominance (DomA), relative dominance (DomR), absolute frequency (FA), relative frequency (FR) and the importance value index (IVI). The 3 species with the highest IVI are indicated in bold type.

| N° | Species | DenTha | Cob | DenA | DenR | DomA | DomR | FA | FR | IVI

(100%) |

| 1 | Lippia graveolens

Mimosa polyantha Randia nelsonii Parthenium fruticosum Total |

1,176.53

305.03 174.30 87.15 1,743 |

1,837.95

1,589.39 675.37 65.40 4,168.14 |

0.67

0.17 0.1 0.05 1 |

67.5

17.5 10 5 100 |

0.44

0.38 0.16 0.02 1 |

44.10

38.13 16.20 1.57 100 |

0.53

0.21 0.16 0.11 1 |

52.63

21.05 15.79 10.53 100 |

54.74

25.56 14 5.70 100 |

| 2 | Acaciella angustissima

Mimosa polyantha Croton morifolius Lippia graveolens Aeschynomene compacta Total |

914.67

625.83 336.99 144.42 48.14 2,070.05 |

2,507.88

2,069.50 290.69 230.26 234.80 5,333.13 |

0.44

0.30 0.16 0.06 0.02 1 |

44.19

30.23 16.28 6.98 2.33 100 |

0.47

0.39 0.05 0.04 0.04 1 |

47.02

38.80 5.45 4.32 4.40 100 |

0.33

0.33 0.19 0.10 0.05 1 |

33.33

33.33 19.05 9.52 4.76 100 |

41.51

34.12 13.59 6.94 3.83 100 |

| 3 | Parthenium fruticosum

Lippia graveolens Mimosa polyantha Randia nelsonii Total |

1,293.46

739.12 554.34 123.19 2,710.11 |

2,223.29

1,240.36 1,158.68 591.38 5,213.72 |

0.47

0.27 0.20 0.04 1 |

47.73

27.27 20.45 4.55 100 |

0.43

0.24 0.22 0.11 1 |

42.64

23.79 22.22 11.34 100 |

0.36

0.27 0.27 0.09 1 |

36.36

27.27 27.27 9.09 100 |

42.24

26.11 23.32 8.33 100 |

| 4 | Randia nelsonii

Parthenium fruticosum Lippia graveolens Mimosa polyantha Aeschynomene compacta Cordia curassavica Acaciella angustissima Justicia candicans Total |

583.48

583.48 340.36 243.12 97.25 97.25 48.62 48.62 2,042.18 |

2,924.99

2,916.76 536.55 587.88 325.37 90.68 89.29 46.74 7,518.25 |

0.28

0.28 0.16 0.11 0.04 0.04 0.02 0.02 1 |

28.57

28.57 16.67 11.90 4.76 4.76 2.38 2.38 100 |

0.389

0.388 0.071 0.078 0.043 0.012 0.012 0.006 1 |

38.91

38.80 7.14 7.82 4.33 1.21 1.19 0.62 100 |

0.26

0.19 0.19 0.15 0.07 0.07 0.04 0.04 1 |

25.93

18.52 18.52 14.81 7.41 7.41 3.70 3.70 100 |

31.13

28.63 14.11 11.51 5.50 4.46 2.42 2.24 100 |

| 5 | Lippia graveolens

Mimosa polyantha Acaciella angustissima Randia nelsonii Parthenium fruticosum Total |

2,130.68

573.64 327.80 245.85 163.90 3,441.87 |

3,177.43

1,763.05 419.76 418.62 298.44 6,077.29 |

0.61

0.16 0.09 0.07 0.04 1 |

61.90

16.67 9.52 7.14 4.76 100 |

0.52

0.29 0.07 0.07 0.05 1 |

52.28

29.01 6.91 6.89 4.91 100 |

0.45

0.27 0.14 0.09 0.05 1 |

45.45

27.27 13.64 9.09 4.55 100 |

53.21

24.32 10.02 7.71 4.74 100 |

Although the tropical deciduous forest we studied in San José Tilapa did not exhibit a high level of species richness, our physiognomic analysis revealed the presence of taxa that are characteristic of this plant community, such as neotropical plant families and some genera such as Apocynaceae (Plumeria), Cordiaceae (Cordia), Burseraceae (Bursera), Cactaceae (Myrtillocactus, Pachycereus, and Opuntia), Euphorbiaceae (Euphorbia and Croton), Fabaceae (Acacia, Mimosa, Parkinsonia, Senna), and Malvaceae (Ceiba), which coincides with previous research conducted in other tropical deciduous forests of Mexico (Bravo-Bolaños et al., 2016; Gallardo-Cruz et al., 2005; León-de la Luz et al., 2012; Lott & Atkinson, 2010; Méndez-Toribio et al., 2014; Pineda-García et al., 2007; Rzedowski, 1978; Sánchez-Mejía et al., 2007; Sánchez-Velásquez et al., 2002; Sousa, 2010; Trejo, 2010). These families have also been important in the secondary communities of the TDF (Beltrán-Rodríguez et al., 2018).

The Fabaceae family has not only been classified as one of the most diverse families, but it also was abundantly represented in these plant communities. A high number of individuals were recorded in this study (n = 90), which is in agreement with reports published by Gallardo-Cruz et al. (2005) and Méndez-Toribio et al. (2014). Although these authors conducted their studies using different methods (Table 6), they recorded a high number of individuals from the Fabaceae family. According to Rzedowski and Calderón-de Rzedowski (2013), species of the genus Acacia and Mimosa that occur in San José Tilapa are exclusive or preferent of the TDF. Other taxa that are distinctive to the TDF studied were Cordia (Cordiaceae), Euphorbia (Euphorbiaceae), and Randia (Rubiaceae), which are genera reported by Rzedowski and Calderón-de Rzedowski (2013).

Table 5

Jaccard similarity indices among the transects (T1-T5): in parentheses, the total number of species compared and the shared species are indicated, the highest value is in bold type.

| Transects | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 |

| T1 | – | ||||

| T2 | 50.0% (16/8) | – | |||

| T3 | 64.3% (14/9) | 43.8% (16/7) | – | ||

| T4 | 52.6% (19/10) | 45.0% (20/9) | 55.6% (18/10) | – | |

| T5 | 60% (15/9) | 50.0% (16/8) | 76.9% (13/10) | 52.6% (19/10) | – |

Table 6. Comparative table including richness (N) and the Shannon-Wiener (H’) and Pielou (J’) indices recorded in studies of structure and floristic composition of the Mexican tropical deciduous forest. Values recorded in this study are in bold type.

| N

range |

H’

range |

H’

average |

J’

range |

J’

average |

|

| Gallardo-Cruz et al. (2005) (plots) | 21 – 39 | 2.12 – 3.16 | – | 0.67 – 0.89 | – |

| Rocha-Loredo et al. (2010) (plots) | 13 -14 | –

– |

2.1 ± 0.07

2.3 ± 0.017 |

–

– |

0.83 ± 0.02

0.86 ± 0.05 |

| Dzib-Castillo et al. (2014) (plots) | 6 – 15 | 0.94 – 2.24 | 1.91 | 0.43 – 0.84 | 0.63 |

| Méndez-Toribio et al. (2014) (plots) | 7 – 56 | 0.41 – 2.69 | 1.98 | – | – |

| Trejo (2005) | 29 | – | 2.96 | – | 0.88 |

| This study

(transects) |

12 – 22 | 0.67 – 2.42 | 2.07 | 0.71 – 0.87 | 0.74 |

It is well-documented that the Cactaceae family, which occurs in Mexico’s tropical deciduous forests, places its characteristic seal on the dry season with its various biological forms (Rzedowski, 1978; Trejo, 1999, 2005), and the physiognomy of the TDF on El Picante hill is no exception: there were arborescent life forms (Opuntia) quantified in 4 transects, along with branched columnar cacti (Myrtillocactus geometrizans and Pachycereus weberi) and globular cacti (Coryphantha pallida) present in the vicinity of the sampling sites. This coincides with the research of Bravo-Bolaños et al. (2016) in the TDF of the coastal region of Banderas Bay in Nayarit, who reported the presence of cacti of the genera Pachycereus and Opuntia. Another life form that enriched the physiognomy we observed were the rosettes, represented by the genus Agave (Asparagaceae) and absent only in the T2 transect.

The physiognomy of the TDF was characterised by trees that varied in height from 4 to 15 m. However, their mean height ranges from 8 to 12 m, and some exceptional isolated life forms that reach heights of ca. 15 m are present in this community (Challenger & Soberón, 2008; Miranda & Hernández, 1963; Pennington & Sarukhán, 2005; Rzedowski, 1978; Trejo, 1998). With regard to height and canopy cover, among the trees and shrubs of the TDF under study, Ceiba aesculifolia, Mimosa polyantha and Randia nelsonii, respectively, were the

most notable.

Analysis of the horizontal structure of the tree stratum in the tropical deciduous forest revealed 5 species that showed relatively high importance indices (IVIs): Ceiba aesculifolia, Bursera morelensis, B. aptera, Parkinsonia praecox, and Fouquieria formosa. The results of this study coincide with 7 species reported by Méndez-Toribio et al. (2014), whose research was conducted in Tziritzícuaro, Balsas Depression, Michoacán. However, there are differences in the IVI, since Méndez-Toribio et al. (2014) reported low values for C. aesculifolia, while Acacia cochliacantha, Cyrtocarpa procera, Euphorbia schlechtendalii, Plumeria rubra (4.33%), and Randia nelsonii recorded higher IVI values than those obtained in the TDF of San José Tilapa.

Bravo-Bolaños et al. (2016) reported various tree and shrub genera with high IVI values such as Acacia, Bursera, Enterolobium, Eysenhardtia, Ficus and Plumeria from the tree stratum, while for the shrub stratum Bauhinia, Celtis, Mimosa, Opuntia, Randia and Ziziphus are mentioned; unfortunately, the values were not specified. Furthermore, Beltrán-Rodríguez et al. (2018) reported a lower value for Euphorbia schlechtendalii (4.8%) and a higher value for Acacia cochliacantha (4.7%) than those recorded in this study.

Upon comparison of the diversity and evenness indices reported in other studies of Mexican tropical deciduous forests (Dzib-Castillo et al., 2014; Gallardo-Cruz et al., 2005; Méndez-Toribio et al., 2014; Rocha-Loredo et al., 2010), with the values found in San José Tilapa, Puebla, in this study (Table 6), it is clear that the values reported are very similar, with the exception of the research performed in Oaxaca by Gallardo-Cruz et al. (2005), which found a higher diversity index is shown (H’ = 3.16).

Severe climate changes have been affected plant communities (Barnosky et al., 2011; Ceballos, García et al., 2010; Ceballos, Martínez et al., 2010; Ceballos et al., 2015). This alteration has caused such an impact in the distribution and phenology of terrestrial ecosystems (Chmura et al., 2019; Donnelly & O’Neill, 2013; Gordo & Sanz, 2010; Richardson et al., 2013; Workie & Debella, 2018). The tropical deciduous forest (TDF) is one of the most significant ecological components at the national level that has been severely altered. Moreover, TDF is well represented at Tehuacán Valley, today considered a megadiverse region with a high level of endemism (Dávila et al., 1993, 2002; Téllez-Valdés et al., 2008; Valiente-Banuet et al., 2000, 2009). Overall, our study documents a low floristic richness of trees and shrubs, probably of an early secondary TDF at the Tehuacán Valley (Mesa-Sierra et al., 2020).

Among the most relevant signs of this study, that must be applied not only in this locality, but also throughout all Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Valley, are the dramatic changes in land use and the effects of climate change on the plant communities. On one hand, this research at El Picante hill provides additional knowledge about TDF distribution, its composition and structure in this valley, and on the other hand, it shows us the need to protect this ecosystem wherever it is less diverse and perhaps more exposed due to human activities that take place in San José Tilapa. We believe that this contribution will enable the community to issue recommendations on the protection of this vulnerable type of vegetation and in the future, it will be important to evaluate the most vulnerable native plant species to human activities and climate change that unfortunately could trigger on habitat fragmentations.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica PAPIIT-DGAPA project IN-108517 “Diversidad palinoflorística y reconstrucción de la vegetación en el Paleógeno y Neógeno de Oaxaca, México”, and project IN-109920 of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, as well as the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa. We are grateful to Thomas F. Daniel for helping us in the Acanthaceae identification to species level. The authors would like to thank the authorities of the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Valley Reserve, and the kindness shown by the community of San José Tilapa, Puebla, in their assistance in the fieldwork carried out on El Picante hill. This paper was translated from the original Spanish by Patrick Weill. Finally, we wish to thank both reviewers and editor Neptalí Ramírez-Marcial, for their valuable comments and suggestions that improve this paper.

References

APG III. (2009). An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG III. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 161, 105–121. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8339.2009.00996.x

Arriaga, L., Espinoza, J. M., Aguilar, C., Martínez, E., Gómez, L., & Loa, E. (Coordinadores) (2000). Regiones terrestres prioritarias de México. Ciudad de México: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad.

Banda, R. K., Delgado-Salinas, A., Dexter, K. G., Linares-Palomino, R., Oliveira-Filho, A., Prado, D. et al. (2016). Plant diversity patterns in neotropical dry forests and their conservation implications. Science, 353, 1383–1387. http://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf5080

Barnosky, A. D., Matzke, N., Tomiya, S., Wogan, G. O. U., Swartz, B., & Quental, T. B. et al. (2011). Has the Earth’s sixth mass extinction already arrived? Nature, 471, 51–57. http://doi.org/10.1038/nature09678

Beltrán-Rodríguez, L., Valdez-Hernández, J. I., Luna-Cavazos, M., Romero-Manzanares, A., Pineda-Herrera, E., Maldonado-Almanza, B. et al. (2018). Estructura y diversidad arbórea de bosques tropicales caducifolios secundarios en la Reserva de la Biósfera Sierra de Huautla, Morelos. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 89, 108–122. http://doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2018.1.2004

Bravo-Bolaños, O., Sánchez-González, A., De Nova-Vázquez, J. A., & Pavón Hernández, N. P. (2016). Composición y estructura arbórea y arbustiva de la vegetación de la zona costera de Bahía de Bandera, Nayarit, México. Botanical Sciences, 94, 603–623. http://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.461

Ceballos, G., Ehrlich, P. R., & Barnosky, A. D., & García, A. (2015). Accelerated modern human-induced species losses: entering the Sixth Mass Extinction. Science Advances, 1, 1–5. e1400253. http://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1400253

Ceballos, G., & García, A. (1995). Conserving Neotropical Biodiversity: The Role of Dry Forest in Western México. Conservation Biology, 9, 1349–1353. http://doi.org/10.1046/J.1523-1739.1995.09061349.x

Ceballos, G., García, A., & Ehrlich, P. R. (2010a). The Sixth Extinction Crisis Loss of Animal Populations and Species. Journal of Cosmology, 8, 1821–1831.

Ceballos, G., Martínez, L., García, A., Espinoza, E., Bezaury Creel, J, & Dirzo, R. (Eds.), (2010b). Diversidad, amenazas y áreas prioritarias para la conservación de las selvas secas del Pacífico de México. Ciudad de México: Fondo de Cultura Económica/ Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad.

Challenger, A., & Soberón, J. (2008). Los ecosistemas terrestres. In J. Sarukhán (Coordinador General), Capital Natural de México, vol I. Conocimiento actual de la biodiversidad. México D.F.: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad.

Chmura, H. E., Kharouba, H. M., Ashander, J., Ehlman, A. M., Rivest, E. B., & Yang L. H. (2019). The mechanisms of phenology: the patterns and processes of phenological phenological shifts. Ecological Monographs, 89, e01337. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecm.1337

Conabio (Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad). (2011). La Biodiversidad en Puebla: Estudio de Estado. México. Ciudad de México: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, Gobierno del Estado de Puebla, Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla.

Conafor (Comisión Nacional Forestal)-Semarnat (Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales). (2012). Inventario nacional forestal y de suelos. Informe 2004-2009. Jalisco, México. Recuperado el 06 de junio, 2019 de: https://www.conafor.gob.mx/biblioteca/Inventario-Nacional-Forestal-y-de-Suelos.pdf

Dávila-Aranda, P., Villaseñor-Ríos, J. L., Medina-Lemos, R., Ramírez-Roa, A., Salinas-Tovar, A., Sánchez-Ken, J. et al. (1993). Listados Florístico de México. X. Flora del Valle de Tehuacán-Cuicatlán. Ciudad de México: Instituto de Biología. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Dávila, P., Arizmendi, M. C., Valiente-Banuet, A., Villaseñor, J. L., Casas, A., & Lira, R. (2002). Biological diversity in the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Valley, México. Biodiversity and Conservation, 11, 421–442. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014888822920

Dirzo, R. (1994). Diversidad de flora mexicana. Ciudad de México: Agrupación Sierra Madre, S.C.

Dirzo, R., Young, H. S., Mooney, H. A., & Ceballos, G. (Eds,), (2011). Seasonally dry tropical forest: ecology and conservation. Washington D.C.: Island Press.

Donnelly, A., & O’Neill, B. (Eds.), (2013). Climate change impacts on phenology implications for terrestrial ecosystems: environmental protection agency. Co. Wexford: Environmental Protection Agency.

Dzib-Castillo, B., Chanatásig-Vaca, C., & González-Valdivia, N. A. (2014). Estructura y composición en dos comunidades arbóreas de la selva baja caducifolia y mediana subcaducifolia en Campeche, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 85, 167–178. http://doi.org/10.7550/rmb.38706

Flores, M. G., Jiménez, L. J., Madrigal, S. X., Moncayo, R. F., & Takaki, T. F. (1971). Memoria del mapa de tipos de vegetación de la República Mexicana. Ciudad de México: Secretaría de Recursos Hidráulicos (SRH).

Gaillard-de Benítez, C., & Pece, M. G. (2011). Muestreo de técnicas de evaluación de vegetación y fauna. Santiago del Estero, Argentina: Universidad Nacional de Santiago del Estero.

Gallardo-Cruz, J. A., Meave, J. A., & Pérez-García, E. A. (2005). Estructura, composición y diversidad de la selva baja caducifolia del Cerro Verde, Nizanda (Oaxaca), México. Boletín de la Sociedad Botánica de México, 76, 19–35. http://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.1701

García, E. (2004). Modificaciones al sistema de clasificación climática de Köppen. Ciudad de México: Instituto de Geografía, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

González-Medrano, F. (2003). Las comunidades vegetales de México. Ciudad de México: Instituto Nacional de Ecología (INE-Semarnat).

Gordo, O., & Sanz, J. J. (2010). Impact of climate change on plant phenology in Mediterranean ecosystems. Global Change Biology, 16, 1082–1106. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.02084.x

Hansen, M. C., Potapov, P. V., Moore, R., Hancher, M., Turubanova, S. A., & Tyukavina, A. et al. (2013). High-resolution global maps of 21st-Century forest cover change. Science, 342, 850–853. http://doi.org/10.1126/science.1244693

INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía). (1980). Carta de uso del suelo y vegetación, clima, temperatura, precipitación, geología, edafología. Atlas Nacional del Medio Físico. Secretaría de Programación y Presupuesto, esc. 1:1 000 000.

INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía). (2003). Conjunto de datos vectoriales de la carta de vegetación primaria 1:1 000 000. Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática, Aguascalientes.

INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía). (2009). Prontuario de información geográfica municipal de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Coxcatlán, Puebla. Clave geoestadística 21035. Recuperado el 07 de junio, 2019 de: http://www3.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/app/mexicocifras/datos_geograficos/21/21035.pdf

INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía). (2014). Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Recuperado el 07 de junio, 2019 de: http://cuentame.inegi.org.mx/territorio/vegetacion/ss.aspx?tema=T

Janzen, D. H. (1988). Management of habitat fragments in a tropical dry forest: growth. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 75, 105–116. http://doi.org/10.2307/2399468

Jaramillo-Luque, V., & González-Medrano, F. (1983). Análisis de la vegetación arbórea en la provincia florística de Tehuacán-Cuicatlán. Boletín de la Sociedad Botánica de México, 45, 49–64. http://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.1298

Leirana-Alcocer, J. L., Hernández-Betancourt, S., Salinas-Peba, L., & Guerrero-Gónzalez, L. (2009). Cambios en la estructura y composición de la vegetación relacionados con los años de abandono de tierras agropecuarias en la selva baja caducifolia espinosa de la reserva de Dzilam, Yucatán. Polibotánica, 27, 53–70.

León-de la Luz, J. L., Domínguez-Cadena, R., & Medel-Narváez, A. (2012). Florística de la selva baja caducifolia de la Península de Baja California, México. Botanical Sciences, 90, 143–162. http://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.480

Lott, E. J., & Atkinson, T. H. (2010). Diversidad florística. In G. Ceballos, L. Martínez, A. García, E. Espinoza, J. Bezaury Creel, & R. Dirzo (Eds.), Diversidad, amenazas y áreas prioritarias para la conservación de las selvas secas del Pacífico de México (pp. 63–76). Ciudad de México: Fondo de Cultura Económica/ Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad.

Lot, A., & Chiang, F. (1986). Manual de herbario (Administración y manejo de colecciones, técnicas de recolección y preparación de ejemplares botánicos). Ciudad de México: Consejo Nacional de la Flora de México, A.C.

Maass, M., Búrquez, A., Trejo, I., Valenzuela, D., González, M. A., Rodríguez, M. et al. (2010). Amenazas. In G. Ceballos, L. Martínez, A. García, E. Espinoza, J. Bezaury-Creel, & R. Dirzo (Eds.), Diversidad, amenazas y áreas prioritarias para la conservación de las selvas secas del Pacífico de México (pp. 321–348). Ciudad de México: Fondo de Cultura Económica/ Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad.

Magurran, A. E. (1988). Ecological diversity and its measurement. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Magurran, A. E. (2004). Measuring biological diversity. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing.

Masera, O. R., Ordoñez, M. J., & Dirzo, R. (1997). Carbon emissions from Mexican forests: current situation and long-term scenarios. Climatic–Change, 35, 265–295. http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005309908420

Matteucci, S. D., & Colma, A. (1982). Metodología para el estudio de la vegetación. Washington D.C.: Secretaría General de la Organización de los Estados Americanos, Programa Regional de Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico. Serie de Biología. Monografía No. 22.

Meave, J. A., Romero-Romero, M. A., & Salas-Morales, S. H. (2012). Diversidad, amenazas y oportunidades para la conservación del bosque tropical caducifolio en el estado de Oaxaca, México. Ecosistemas, 21, 85–100.

Méndez-Toribio, M., Martínez-Cruz, J., Cortés-Flores, J., Rendón-Sandoval, F. J., & Ibarra-Manríquez, G. (2014). Composición, estructura y diversidad de la comunidad arbórea del bosque tropical caducifolio en Tziritzícuaro, Depresión del Balsas, Michoacán, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 85, 1117–1128. http://doi.org/10.7550/rmb.43457

Mesa-Sierra, N., Escobar, F., & Laborde, J. (2020). Appraising forest diversity in the seasonally dry tropical region of the Gulf of Mexico. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 91, e913175. https://doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2020.91.3175

Miles, L., Newton, A. C., DeFries, R. S., Ravilious, C., May, I., Blyth, S. et al. (2006). A global overview of the conservation status of tropical dry forests. Journal of Biogeography, 33, 491–505. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01424.x

Miranda, F. (1948). Datos sobre la vegetación en la Cuenca Alta del Papaloapan. Anales del Instituto de Biología, 19, 333–64.

Miranda, F., & Hernández, X. E. (1963). Los tipos de vegetación de México y su clasificación. Boletín de la Sociedad Botánica de México, 28, 29–176. http://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.1084

Mueller-Dombois, D., & Ellenberg, H. (1974). Aims and methods of vegetation ecology. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Osorio Beristain, O., Valiente-Banuet, A., Dávila, P., & Medina, R. (1996). Tipos de vegetación y diversidad β en el Valle de Zapotitlán de las Salinas, Puebla, México. Boletín de la Sociedad Botánica de México, 59, 35–58. http://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.1504

Pennington, T. D., & Sarukhán, J. (2005). Árboles tropicales de México. Manual para la identificación de las principales especies. México D.F.: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/ Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Pineda-García, F., Arredondo-Amezcua, L., & Ibarra-Manríquez, G. (2007). Riqueza y diversidad de especies leñosas del bosque tropical caducifolio El Tarimo, Cuenca del Balsas, Guerrero. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 78, 129–139. http://doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2007.001.396

Ramírez Bravo, O. E., & Hernández-Santin, L. (2016). Plan diversity along a disturbance gradient in a semi-arid ecosystem in Central México. Acta Botanica Mexicana, 117, 11–25. http://doi.org/10.21829/abm117.2016.1164

Richardson, A. D., Keenan, T. F., Migliavacca, M., Ryu, Y., Sonnentag, O., & Toomey, M. (2013). Climate change, phenology, and phenological control of vegetation feedbacks to the climate system. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 169, 156–173. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2012.09.012

Rocha-Loredo, A. G., Ramírez-Marcial, N., & González-Espinosa, M. (2010). Riqueza y diversidad de árboles del bosque tropical caducifolio en la Depresión Central de Chiapas. Boletín de la Sociedad Botánica de México, 87, 89–103. http://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.313

Rodríguez-Acosta, M., Villaseñor, J. L., Coombes, A. J., & Cerón-Carpio, A. B. (2014). Flora del estado de Puebla. Puebla: Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla/ Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Rzedowski, J. (1978). Vegetación de México. Ciudad de México: Limusa.

Rzedowski, J., & Calderón-de Rzedowski, G. (1987). El bosque tropical caducifolio en la región mexicana del Bajío. Trace, 12, 12–21.

Rzedowski, J., & Calderón-de Rzedowski, G. (2013). Datos para la apreciación de la flora fanerogámica del bosque tropical caducifolio de México. Acta Botanica Mexicana, 102, 1–23. http://doi.org/10.21829/abm102.2013.229

Sánchez-Mejía, Z. M., Serrano-Grijalva, L., Peñuelas-Rubio, O., Pérez-Ruiz, E. R., Sequeiros-Ruvalcaba, E., & García Calleja, M. T. (2007). Composición florística y estructura de la comunidad vegetal del límite del desierto de Sonora y la selva baja caducifolia (Noroeste de México). Revista Latinoamericana de Recursos Naturales, 3, 74–83.

Sánchez-Velásquez, L. R., Hernández-Vargas, G., Carranza, M.A., Pineda-López. M. R., Cuevas, R., & Aragón, F. (2002). Estructura arbórea del bosque tropical caducifolio usado para la ganadería extensiva en el norte de la sierra de Manantlán, México. Antagonismo de Usos. Polibotánica, 13, 25–46.

Smith, C. E. (1965). Flora Tehuacán Valley. Fieldiana Botany, 31,101–143.

Sousa, S. M. (2010). Centros de endemismo: las leguminosas. In G. Ceballos, L. Martínez, A. García, E. Espinoza, J. Bezaury-Creel, & R. Dirzo (Eds.), Diversidad, amenazas y áreas prioritarias para la conservación de las selvas secas del Pacífico de México (pp. 77–92). Ciudad de México: Fondo de Cultura Económica/ Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad.

Téllez-Valdés, O., Reyes-Castillo, M., & Dávila-Aranda, P. (2008). Guía ecoturística: las plantas del Valle de Tehuacán-Cuicatlán. Ciudad de México: VolksWagen/ Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/ Millennium Seed Bank Project KEW.

Trejo, I. (1996). Características del medio físico de la selva baja caducifolia en México. Investigaciones Geográficas Boletín, Número Especial, 4, 95–110.

Trejo, I. (1998). Distribución y diversidad de selvas bajas de México: relaciones con el clima y el suelo (Tesis doctoral). Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México D.F.

Trejo, I. (1999). El clima de la selva baja caducifolia en México. Investigaciones Geográficas Boletín, 39, 40–52. http://doi.org/10.14350/rig.59082

Trejo, I. (2005). Análisis de la diversidad de la selva baja caducifolia en México. In G. Halffter, J. Soberón, P. Koleff, & A. Melic (Eds.), Sobre diversidad biológica: el significado de las diversidades alfa, beta y gamma (pp. 111–122). Zaragoza, España: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad/ Sociedad Entomológica Aragonesa/ Grupo Diversitas-México/ Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, m3m-Monografías 3ercer Milenio.

Trejo, I. (2010). Las selvas secas del Pacífico mexicano. In G. Ceballos, L. Martínez, A. García, E. Espinoza, J. Bezaury-Creel, & R. Dirzo (Eds.), Diversidad, amenazas y áreas prioritarias para la conservación de las selvas secas del Pacífico de México (pp. 41–51). Ciudad de México: Fondo de Cultura Económica/ Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad.

Trejo, I., & Dirzo, R. (2000). Deforestation of seasonally dry tropical forest: a national and local analysis in Mexico. Biological Conservation, 94, 133–142. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(99)00188-3

Valiente-Banuet, A., Casas, A., Alcántara, A., Dávila, P., del Coro Arizmendi, M., Villaseñor, J. L. et al. (2000). La vegetación del valle de Tehuacán-Cuicatlán. Boletín de la Sociedad Botánica de México, 67, 25–74. http://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.1625

Valiente-Banuet, A., Solís, L., Dávila, P., Arizmendi, M. C., Silva-Pereyra, C., Ortega-Ramírez, J. et al. (2009). Guía de la vegetación del valle de Tehuacán-Cuicatlán. Ciudad de México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/ Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad/ Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia/ Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas, Fundación para la Reserva de la Biosfera Cuicatlán.

Villaseñor, J. L., Dávila, P., & Chiang, F. (1990). Fitogeografía del valle de Tehuacán-Cuicatlán. Boletín de la Sociedad Botánica de México, 50, 135–149. http://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.1381

Williams-Linera, G., & Lorea, F. (2009). Tree species diversity by environmental and anthropogenic factors in tropical dry forest fragments of central Veracruz, Mexico. Biodiversity and Conservation, 18, 3269–3293. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-009-9641-3

Workie, T. G., & Debella, H. J. (2018). Climate change and its effects on vegetation phenology across ecoregions of Ethipia. Global Ecology and Conservation, 13, e00366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2017.e00366

Zavala-Hurtado, J. A. (1982). Estudios ecológicos en el valle semiárido de Zapotitlán, Puebla I. Clasificación numérica de la vegetación basada en atributos binarios de presencia o ausencia de las especies. Biotica, 7, 99–120.