José Antonio González-Oreja a, *, Iñigo Zuberogoitia b

a Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Edificio 112-A, Ciudad Universitaria, 72570 Puebla, Puebla, Mexico

b Estudios Medioambientales Icarus S.L., C/ San Vicente 8. 6 ª Planta, Dpto. 8, Edificio Albia I. 48001 Bilbao, Spain

*Corresponding author: jgonzorj@hotmail.com (J.A. González-Oreja)

Received: 2 December 2019; accepted: 5 June 2020

Abstract

After conducting replicated counts of migratory waterbirds at a given wetland, some authors choose to compute the mean abundance throughout the study period, whereas others report the peak value or the cumulative total. Here, we use fictitious and real examples to illustrate how some of these procedures can lead to distorted conclusions. For species with skewed abundance distributions, the mean does not summarize the central tendency in the data, and the median should be used; however, for many migratory waterbirds, median abundances at a given site can be null. Also, the probability of double-counting the same individuals increases when replicated surveys cover a long time. Moreover, since the cumulative abundance of a species/assemblage increases with the number of surveys, misleading results can be obtained if researchers apply different sampling efforts. Finally, the ranking and selection of wetlands for waterbird conservation can be misguided if cumulative totals are compared against standard criteria (i.e., Ramsar sites, IBAs). To avoid the above mentioned problems, we propose to use the maximum, peak abundance of a given waterbird species during the course of the study, or the sum of maxima, peak values across all the species in the same waterbird assemblage.

Keywords: Wetlands; Migratory birds; Number of individuals; Peak abundance; Cumulative total; Ecology; Conservation

© 2020 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license

Resumiendo los cambios en abundancia de las aves acuáticas: algunos problemas y una posible solución

Resumen

Después de censar en repetidas ocasiones a las aves migratorias de un humedal, algunos autores optan por calcular la abundancia media a lo largo del tiempo estudiado, mientras que otros consideran el valor máximo, o el total acumulado. Mediante ejemplos reales y ficticios, ilustramos aquí cómo algunos de estos procedimientos pueden inducir a errores no intencionados en materia de ecología y conservación de aves acuáticas. En especies con distribuciones de abundancia sesgadas, la media no resume la tendencia central de los datos, por lo que debería usarse la mediana; pero para muchas aves acuáticas migratorias, la mediana de sus abundancias en un humedal determinado puede ser cero. Además, la probabilidad de contar por duplicado a los mismos individuos aumenta cuando el tiempo estudiado es largo. Es más, se pueden obtener resultados erróneos si se utilizan diferentes esfuerzos de muestreo, ya que la abundancia acumulada de una especie o de una comunidad aumenta con el número de censos. En fin, la priorización y selección de humedales para la conservación de las aves acuáticas puede realizarse de modo equivocado si las abundancias totales acumuladas se comparan con los criterios estandarizados del programa Ramsar o de los sitios IBA. De cara a evitar estos problemas, sugerimos utilizar la abundancia máxima de una especie de ave acuática registrada a lo largo del tiempo estudiado, o la suma de los máximos para todas las especies de aves acuáticas en la misma comunidad.

Palabras clave: Humedales; Aves migratorias; Número de individuos; Abundancia máxima; Abundancia acumulada; Ecología; Conservación

© 2020 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. Este es un artículo Open Access bajo la licencia CC BY-NC-ND

Introduction

Many bird species complete seasonal migration movements between their breeding range and non-breeding areas, such as stopover and wintering range, which allows them to exploit different environments with contrasting importance for survival and reproduction (Newton, 2010; Rappole, 2013). A number of migratory birds depend on wetlands and can be considered as waterbirds (van der Valk, 2012). There is abundant evidence that during the 20th Century, in many parts of the world, wetlands have been strongly degraded (Millenium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005). In fact, the conservation status of wetland wildlife, waterbirds included, is deteriorating faster than that of terrestrial species (Millenium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005; Rosenberg et al., 2019, for a recent survey in North America; Shuter et al., 2011). Therefore, it is important to track temporal changes in the abundance of migratory waterbirds (Gray et al., 2013; Wetlands International, 2010).

Many migratory waterbirds congregate their populations in a small number of sites during certain periods of the year, which could render their counting easier to perform (Henderson, 2003; Weller, 2004). By correctly undertaking repeated counts at the same study site at different points through time, one can study temporal changes in bird numbers (Greenwood & Gibbons, 2008; Gregory et al., 2004). The study of temporal trends in populations can be applied to assess the carrying capacity at a given environment (Alonso et al., 1994), or to evaluate progress toward a management goal (Elzinga et al., 2001), which is usually part of a larger monitoring program (Greenwood & Robinson, 2006). Although monitoring wetland wildlife is difficult, and diverse techniques are usually needed to obtain robust population estimates (Gray et al., 2013), waterbirds are among the best monitored animals throughout the world (van der Valk, 2012; Wetlands International, 2010), and many authors have studied seasonal and/or inter-annual changes in the abundance of waterbirds. For instance, Russell et al. (2014) examined how the distribution and abundance of 54 waterbird species changed between 1992 and 2010 in a rare wetland type in South Africa. To update our knowledge of a critically endangered species, the Spoon-billed Sandpiper (Calidris pygmaea), Zӧckler et al. (2016) described field surveys undertaken between 2005 and 2013 in several countries along the East Asian-Australasian flyway. And Molina et al. (2018) documented how the distribution, density and population structure of American Avocets (Recurvirostra americana) wintering in a biosphere reserve in Mexico changed between 2010 and 2013.

In ecology, a census is the result of counting all the individuals within a group of interest in a well-defined area and time interval (Southwood & Henderson, 2016; Thompson et al., 1998). Without correcting for detectability (Buckland et al., 2008; MacKenzie et al., 2018), field-based census methods can work for relatively few bird species, and only at small spatial or temporal scales, where all individuals could be counted. Nevertheless, the complete enumeration of all the individuals in a given population can be costly, time-consuming and inefficient (Greenwood & Robinson, 2006; McComb et al., 2010). More likely, total counts result unattainable, and samples must be taken to statistically estimate the size of the population (Fasham & Mustoe, 2005; Jones, 2000). Actually, a large number of factors can lead to estimates of population size that are unacceptably above or below the true value, including a poor sampling strategy, an inappropriate field method, or the unintentional double counting of the same birds during a given census or sampling (Buckland et al., 2008; Gibbons & Gregory, 2006; Gregory et al., 2004; Thompson et al., 1998). Under these circumstances, replicated surveys can not be considered independent, true replicates, and the researcher could incur in a problem of temporal pseudoreplication (for instance, Hurlbert, 1984).

Numbers of birds recorded during fieldwork are often used to infer change over time in waterbird abundance, or to monitor differences in bird numbers amongst habitats or regions (Buckland et al., 2008). After conducting replicated counts of waterbirds at different time intervals, some authors choose to summarize obtained data by computing one of the following simple statistics (Nur et al., 1999): the total (cumulative) abundance of the studied species throughout the study period; the mean (average) value, or the maximum (peak) one. This should be decided in advance, and only after taking into account the goals of the study (Greenwood & Robinson, 2006). In this paper, we 1) analyze some procedures researchers usually apply in summarizing their studies of temporal changes in the abundance of waterbird populations or assemblages; 2) illustrate how these practices can inadvertently lead to distorted conclusions if obtained results are applied in ecological studies, or to rank wetlands for waterbird conservation purposes, and 3) suggest a simple solution to standardize approaches and avoid these problems.

Materials and methods

To illustrate some of the problems researchers face when using mean (average) abundance values to document the importance of a given wetland for waterbirds, we will use a fictitious scenario. Let us assume that the total world population of an endangered migratory waterbird ―from now on, Rarita rarita― is estimated at 1,000 individuals (Table 1). Let us assume, also, that the entire population of this species can be found at a given wetland 1 for only 1 month, whereas half the population, always the same 500 individuals, inhabit wetland 2 during the rest of the year. Then, following Greenwood & Robinson (2006), wetland 1 might be considered more important for our focal species than wetland 2. For this result, we simply computed the mean abundance of the species at both wetlands. An observant reader could realize that our fictitious values were highly skewed (Table 1). When distributions are strongly skewed, the median is often preferred over the mean because it summarizes best what is typical in the data (Agresti & Franklin, 2013). In fact, several authors used median abundances in their waterbird studies (for instance, Martínez-Curci et al., 2015; Wilson et al., 2014). Therefore, we also computed the median abundance of R. rarita at both wetlands.

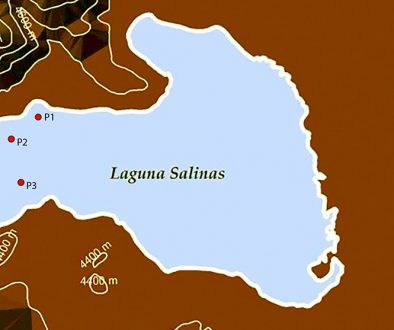

We also use an ecological, real dataset to illustrate the same point. For this end, we used our own dataset describing seasonal changes in the waterbird assemblage at “Presa de Valsequillo,” a Ramsar site in Puebla, Mexico (Berumen-Solórzano et al., 2017). From February 2014 to January 2015, monthly surveys were completed, except for April and July, and 30 waterbird species were retained for study. For all the waterbird species in the Valsequillo dataset (Table 1), we used PAST vers. 3.22 to compute the sample skewness (G1); G1 = 0 for normally distributed data, G1 > 0 for a long tail to the right, and G1 < 0 for a tail to the left (Hammer, 2018). Computer intensive methods could be used to obtain confidence intervals for skewness measures; yet, even the “best,” bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrap confidence intervals give “suspect” results for samples under size 30 (Good, 2005); then, we report here only point estimates for G1.

Instead of reporting the mean (average) or the maximum (peak) abundance, researchers can also compute the total (cumulative) abundance of the species throughout the study period (Nur et al., 1999). Although, this practice can also yield ecologically misleading results. We illustrate some problems researchers can face when using total (cumulative) abundance values to document the ornithological importance of a given wetland by using our fictitious example previously explained.

Results

Regarding our fictitious scenario, if 10 censuses were regularly taken throughout the year at both wetlands 1 and 2, the mean abundance of R. rarita at wetland 1 would be 100 individuals (Table 1). However, this value was never observed in the field, and can hardly be deemed a valid measure of the central tendency of the abundance of the species at wetland 1. Moreover, the median abundance of R. rarita at wetland 1 also results ecologically irrelevant since it is zero (Table 1).

Regarding our real dataset from “presa de Valsequillo,” some waterbird species were registered only twice, like the Franklin’s Gull (Leucophaeus pipixcan: 1 bird was observed in October, and 3 in November), or even once, like the Black-bellied Whistling-duck (Dendrocygna autumnalis: 33 birds were observed in December). Indeed, for exceedingly rare species inhabiting wetlands, detection can be near zero (Gray et al., 2013). Had we computed mean abundances from those 10 samples, the average values for Franklin’s Gulls (0.4 birds/survey) and Black-bellied Whistling-ducks (3.3 birds/survey) would have been ecologically irrelevant. Our analyses with the Valsequillo dataset reveal that skewness values in abundance data suggested asymmetric, positively skewed distributions for 13 out of the 30 species retained for study (Table 1). Therefore, the median (but not the mean) should theoretically be used as a measure of the central tendency of the corresponding distributions. Nevertheless, the median was 0 for 12 out of the 30 species in our dataset, and the frequency of this result increased with the measure of skewness (Table 1). This suggests that, at least for species with a low frequency of occurrence, the median is not a good measure summarizing abundance values.

Table 1

Temporal changes in the abundance of an endangered migratory waterbird, Rarita rarita, at 2 wetlands (fictitious values). Temporal changes in the abundance of 30 waterbird species at “presa de Valsequillo,” a Ramsar site in Puebla, Mexico (Berumen-Solórzano et al. 2017). For each species (row): Sum = the total, cumulative abundance throughout the sampled months; Max = the maximum (peak) abundance; Skew = the sample skewness (G1); Mean = the (arithmetic) average, and Med = the median abundance. Those species with Med = 0 have been marked with an asterisk (*).

| Month | Summary | |||||||||||||||

| F | M | My | J | A | S | O | N | D | Jn | Sum | Max | Skew | Mean | Median | ||

| Rarita rarita at wetland 1 | 1,000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 3.5 | 100 | 0.0 | * |

| Rarita rarita at wetland 2 | 0 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 4,500 | 500 | -6.9 | 450 | 500 | |

| Dendrocygna autumnalis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 0 | 33 | 33 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 0.0 | * |

| Aix sponsa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | * |

| Spatula discors | 72 | 159 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 189 | 65 | 101 | 12 | 609 | 189 | 0.9 | 60.9 | 38.5 | |

| Spatula clypeata | 124 | 9 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 580 | 104 | 12 | 378 | 1,211 | 580 | 1.8 | 121.1 | 10.5 | |

| Mareca strepera | 13 | 79 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 34 | 145 | 179 | 450 | 179 | 1.4 | 45 | 6.5 | |

| Mareca americana | 81 | 59 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 103 | 32 | 60 | 335 | 103 | 0.7 | 33.5 | 16 | |

| Anas platyrrhynchos diazi | 62 | 69 | 97 | 74 | 92 | 62 | 10 | 76 | 84 | 22 | 648 | 97 | -1.1 | 64.8 | 71.5 | |

| Anas acuta | 85 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 40 | 133 | 85 | 2.3 | 13.3 | 0.0 | * |

| Anas crecca | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 21 | 0 | 40 | 21 | 2.1 | 4 | 0.0 | * |

| Aythya americana | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 3.1 | 1 | 0.0 | * |

| Aythya affinis | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 27 | 2.9 | 3.3 | 0.0 | * |

| Oxyura jamaicensis | 69 | 312 | 26 | 60 | 3 | 4 | 43 | 358 | 140 | 46 | 1,061 | 358 | 1.4 | 106.1 | 53 | |

| Podilymbus podiceps | 2 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 22 | 1 | 2 | 11 | 8 | 2 | 56 | 22 | 1.9 | 5.6 | 2 | |

| Podiceps nigricollis | 6 | 151 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 53 | 63 | 14 | 5 | 301 | 151 | 2.1 | 30.1 | 6 | |

| Gallinula galeata | 41 | 5 | 9 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 30 | 48 | 147 | 48 | 1.2 | 14.7 | 4.5 | |

| Fulica americana | 1,113 | 931 | 343 | 130 | 254 | 265 | 1,853 | 2,341 | 2,998 | 1,910 | 12,138 | 2,998 | 0.5 | 1,213.8 | 1,022 | |

| Leucophaeus pipixcan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 2.7 | 0.4 | 0.0 | * |

| Phalacrocorax auritus | 0 | 2 | 9 | 14 | 19 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 57 | 19 | 1 | 5.7 | 2 | |

| Pelecanus erythrorhynchos | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 7 | 12 | 34 | 15 | 1.4 | 3.4 | 0.0 | * |

| Tigrisoma mexicanum | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 8 | 6 | 2.9 | 0.8 | 0.0 | * |

| Ardea herodias | 11 | 15 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 15 | 35 | 45 | 43 | 176 | 45 | 0.8 | 17.6 | 13 | |

| Ardea alba | 83 | 12 | 30 | 77 | 133 | 530 | 262 | 380 | 33 | 66 | 1,606 | 530 | 1.4 | 160.6 | 80 | |

| Egretta thula | 1 | 9 | 10 | 5 | 67 | 131 | 67 | 323 | 9 | 5 | 627 | 323 | 2.3 | 62.7 | 9.5 | |

| Egretta caerulea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 12 | 8 | 2.8 | 1.2 | 0.0 | * |

| Egretta tricolor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 18 | 8 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 0.5 | |

| Bubulcus ibis | 2 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 149 | 31 | 5 | 294 | 149 | 1.9 | 29.4 | 3.5 | |

| Butorides virescens | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 5 | 2 | 0.9 | 0.0 | * |

| Nycticorax nycticorax | 4 | 0 | 15 | 18 | 10 | 41 | 156 | 104 | 10 | 9 | 367 | 156 | 1.8 | 36.7 | 12.5 | |

| Eudocimus albus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1.8 | 0.2 | 0.0 | * |

| Plegadis chihi | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 19 | 39 | 237 | 26 | 4 | 350 | 237 | 3 | 35 | 12 | |

| Totals | 1,784 | 1,832 | 568 | 384 | 628 | 1,080 | 3,386 | 4,457 | 3,792 | 2,859 | 20,770 | 6,406 | 2,077 |

Remember the world population of our fictitious endangered waterbird, R. rarita, was estimated at 1,000 individuals. If one computes the total, cumulative abundance of this species for both wetlands in our example (Table 1), this value is 1,000 for wetland 1, which is ecologically correct, but it is 4,500 (i.e., 9 months × 500 birds/month) for wetland 2. An inattentive reader could interpret the last value as if 4,500 “different birds” were registered in the study area, all at the same time; however, the peak, maximum abundance per survey was only 500, and the whole population was only 1,000. On the other hand, 4,500 “different birds” could have also been observed if their identity completely changed over time, i.e., if the turnover among individual waterbirds was complete. However, this was not the case in our fabricated example, since the individuals in wetland 2 were always the same and, again, the whole population was only 1,000. Finally, it should be noted that, if wetland 2 were regularly surveyed throughout the year once-a-month, the total, cumulative abundance of R. rarita would be 5,500 (i.e., 11 months × 500 birds/month).

Discussion

As our fictitional and real data expose, both mean abundances and total, cumulative values through time can be ecologically misleading. On the one hand, mean abundances can be markedly skewed, and median values should be used; but median values can also be ecologically meaningless, if never registered in the field. Therefore, reporting the maximum (peak) abundance could be the best option for our data, and this might also be true for real datasets, since biological variables frequently are positively skewed (Quinn & Keough, 2002). On the other hand, total, cumulative values can inadvertently count the same individuals multiple times. In fact, the total, cumulative abundance of a given species at a given site unavoidably increases with the actual number of samples/surveys taken.

Actually, we have found this procedure of reporting the total, cumulative abundance of a population, or a whole assemblage, several times in the recent literature on temporal changes of migratory waterbirds in Mexico. The following references should only be taken as a small (n = 15) and surely biased sample, included here just to illustrate our point: Guzmán et al. (1994); Cupul-Magaña (1997, 2000); Hernández-Vázquez (2000, 2005); Mellink and De la Riva (2005); Munguía et al. (2005); Amador et al. (2006); Zárate-Ovando et al. (2006); Gerardo-Tercero et al. (2010); Sánchez-Bon et al. (2010); Fonseca et al. (2012); Mera-Ortiz et al. (2016); Hernández-Colina et al. (2018), and Molina et al. (2018). The interested reader can also see this procedure in Arizaga et al. (2014) or Isotti et al. (2015), for instance. Interestingly, several of these authors reported the total, cumulative abundance but also other measures of the central tendency in the abundance of their study species or assemblages.

Because of their contrasting objectives and survey protocols during field work, the number of samples/surveys also varied dramatically amongst the abovementioned studies reporting total, cumulative abundance. For example, to document spatio-temporal changes in the distribution and abundance of waterbirds wintering in “ciénega de Tláhuac,” a lacustrine wetland in Mexico, Ayala-Pérez et al. (2013) completed only 4 surveys, 1 per month. On the other hand, to study if the formation of an artificial lagoon affected waterbird diversity in Urdaibai, a biosphere reserve in Spain, Arizaga et al. (2014) surveyed waterbirds 24 times, 1 survey per 15-d interval. Without doubt, total, cumulative abundance data for species or assemblages obtained from studies with so dissimilar sampling efforts cannot be directly compared.

Furthermore, 86.7% of the studies in our abovementioned sample of references reported the total, cumulative abundance of the studied waterbirds in the corresponding ‘Abstract/Summary’ sections of their publications. In this way, those numbers received a wider audience, since this is the most read part of a published article (Gladon et al., 2011), and it can be freely available via abstracting services and/or search engines (British Ecological Society, 2015). Therefore, after reading the ‘Abstract/Summary’ section of the abovementioned papers, an unobservant reader might obtain an ecologically misleading idea about the abundance of waterbirds in the study wetlands.

Among the potential confusions that could be caused by reporting the total (cumulative) abundance of waterbirds is the fact that it allows for improper comparisons between study sites. For instance, Mera-Ortiz et al. (2016) studied temporal changes in the composition and abundance of waterbirds at “mar Muerto,” a coastal lagoon in Oaxaca-Chiapas, Mexico. After visiting, once per month, 3 different landscapes in this lagoon during March, April, May and September 2011, they registered 40 species of aquatic and semi-aquatic birds and reported a total, cumulative abundance of 1,577 individuals. Then, Mera-Ortiz et al. (2016) compared these values with those previously reported for similar wetlands along the tropical, Mexican Pacific coast, and concluded that waterbird assemblages inhabiting “mar Muerto” exhibited low richness and abundance (Gerardo-Tercero et al., 2010; Hernández-Vázquez, 2005; Sánchez-Bon et al., 2010). Moreover, authors proposed putative ecological explanations to support their conclusion, taking into account vegetation differences among the study sites.

And yet, the conclusion by Mera-Ortiz et al. (2016) might be biased, since the studies they used in their comparisons had followed the same procedure we are criticizing here. First, from December 1997 to November 1998, Hernández-Vázquez (2005) completed monthly surveys in 2 natural water pools in Jalisco, Mexico, and reported a total, cumulative abundance of 66,976 individuals (78 species) for one site, and 112,832 individuals (73 species) for the other site. Also, from October 1996 to May 1997, Gerardo-Tercero et al. (2010) completed 8 surveys in total at 3 different environmental units in a coastal lagoon in Chiapas, Mexico, and reported a total, cumulative abundance of 89,413 individuals (39 species). Finally, after completing 1 census per month from July 2006 to June 2007 at several sampling sites in a coastal lagoon complex in Sinaloa, Mexico, Sánchez-Bon et al. (2010) reported a total, cumulative abundance of 55,849 individuals (71 species). It is impossible for us to know the real survey effort employed in these studies, but undoubtedly it was heterogeneous enough to make direct comparisons of abundance values not feasible. Many authors have observed that, when sampling effort varies between study sites, direct comparisons of richness values are not possible (Gotelli & Colwell, 2011; Gotelli & Ellison, 2013; and references therein).

We think the same is true for total, cumulative abundance values, but it seems to us that this significant point has been frequently forgotten. Fortunately, several authors have developed standardized protocols for surveying waterbirds of conservation concern, like marsh-dependent birds in North America or marine birds in Alaska, which allow researchers to obtain consistent results among locations and gain a better knowledge of the status, distribution and population trends of selected species (Conway, 2011; Smith et al., 2014).

At least 2 global biodiversity conservation schemes consider data on waterbird abundance to ascribe conservation status to wetlands all through the world: the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance, also known as the Ramsar Convention (https://www.ramsar.org/), and the BirdLife International, Important Bird Areas (IBA) program (https://www.birdlife.org/). In summary, a given site could be included onto the List of Wetlands of International Importance (at the time of the writing, 2,341 Ramsar sites), or considered as IBA (at the time of the writing, more than 12,000 IBAs; sic), if it is known or thought to support, on a regular basis, at least 20,000 waterbirds of 1 or more species (Ramsar Criterion 5, IBA Criterion A4iii), or at least 1% of the individuals in a biogeographic population of a congregatory species or subspecies (Ramsar Criterion 6, IBA Criterion A4i).

Note that, as previously stated, these criteria do not clarify what type of abundance values should be considered when applying both thresholds to infer the conservation importance of wetlands for waterbirds (Ramsar Convention Secretariat, 2010). And this is significant since, otherwise, resources for conservation might be misapplied if the inferences about trends or differences in waterbird abundance are inaccurate (Buckland et al., 2008). For instance, Valle et al. (2014) studied seasonal changes in the abundance of waterbirds at a key stopover site on the West Asian-East African flyway, and used peak counts to assess the importance of the Sabaki River Mouth, Kenya, for a number of migratory waterbirds, including the Saunders’s Tern (Sterna saundersi). The maximum abundance of this species (750 individuals) exceeded 1% threshold of its global population, which confirmed the international rank of that estuary. However, we could not determine if other researchers considered total, mean, or peak abundances when evaluating the importance of the studied wetlands for waterbirds (Eiserman & Avendaño, 2009; Vega et al., 2006). This lack of a common approach in assessing the degree of compliance with standard criteria might help to recognize, or to exclude, a given wetland as a Ramsar site or IBA. By ignoring the abovementioned, positive relationship between sampling effort and cumulative abundance, a researcher could complete a large number of surveys at a given study site and unconsciously inflate abundance data, which might exceed the threshold values in the corresponding criteria, and artificially increase the conservation importance of the studied wetland for waterbirds.

Since birds are highly-mobile organisms, determining how many individual birds use a site from counts alone is not an easy task, and many authors advise those who count birds of the importance of not registering multiple times the same individuals (Frost et al., 2019; Lloyd et al., 2000; McComb et al., 2010; Mustoe et al., 2005). To avoid double-counting the same birds at a given time, Gregory et al. (2004) simply recommended using careful observation and common sense, and similar measures have been considered by some researchers studying waterbirds (Cui et al., 2014; Prosser et al., 2017). Nevertheless, when replicated samples/surveys are spread out over time, these simple measures are difficult to apply, if not impossible. In this paper we maintain that, if a simple measure summarizing the abundance of waterbirds is needed, then computing the mean (average) abundance over time of a given species or assemblage, or the total (cumulative) abundance throughout a long study period, could both be ecologically misleading. In the former case, because abundance values could be skewed; in the latter case, because of the non-zero probability of counting the same individual birds multiple times. Therefore, how can we capture with a single number the importance over time of a waterbird species or assemblage?

Following Johnson (2008), we propose to use the maximum, peak abundance of a given species during the course of the study as a simple but ecologically relevant measure of its numerical importance. Actually, this approach has been previously applied by Ayala-Pérez et al. (2013) to study spatio-temporal changes in the distribution of wintering waterbirds in “ciénega de Tláhuac”, a lacustrine plain in Mexico; by Valle et al. (2014) to highlight the importance of the Sabaki River Mouth for a number of waterbirds on the West Asian-East African flyway, and (partially) by Zӧckler et al. (2016) to study the world winter distribution of the critically endangered Spoon-billed Sandpiper. For example, using the Valsequillo dataset (Table 1), the total, cumulative abundance of American Coots (Fulica americana) was ca. 12,150; however, the maximum, peak abundance was registered in December, when ca. 3,000 birds were counted. Also, the cumulative abundance of the endemic Mexican Duck (Anas platyrhynchos diazi) was ca. 650, but the peak was only ca. 100 ducks. These peak abundance values likely underestimate the real number of individuals throughout the study period, since the identity of the birds inhabiting the study site might have changed with time; therefore, we think they ought to be regarded as lower bounds for their corresponding total abundance (Ayala-Pérez et al., 2013).

Moreover, to obtain a reasonable measure of the total number of individuals for whole assemblages, we propose to sum the peak abundance values across all the species during the course of the study. This approach has been successfully applied by the British Trust for Ornithology in their Wetland Bird Survey (Frost et al., 2019; https://app.bto.org/webs-reporting/), which reports site totals for many wetlands in the United Kingdom as the sum of each species maxima from the appropriate time period. Note that, if this time period is short enough (e.g., only 1 year), then the peak abundance could also be misleading, since it could be unrepresentative of the general trend of the population in time. For reasons like this, organizations as the British Trust for Ornithology are using a 5-year mean of peaks to infer site importance (Ramsar Convention Secretariat, 2010). For the Valsequillo dataset (Table 1), the total, cumulative abundance of the 30 studied waterbird species was ca. 20,800 individuals; nevertheless, after adding the peak values across all the species, we obtained an estimate of ca. 6,400 individuals. Note that this number of “different birds” was never registered at the same point in time in our study area, since the highest monthly abundance was ca. 4,450, registered in November (Table 1). Note, finally, that additional, replicated information is required to account for inconsistencies in data and to properly judge the regular basis of peak abundance values in a given wetland; otherwise, we could be confusing sites that regularly hold wintering waterbird populations of national or international importance with those which might happen to exceed the abovementioned thresholds only in occasional winters.

Total, cumulative abundance might offer the most credible (i.e., exact) results for those sites over which migratory birds produce spectacular concentrations and must pass, like well-known narrow migration bottlenecks, where temporal turnover is very high; or for irruptive species (Devenish et al., 2009; Newton, 2010). For the rest of sites and species, common sense tells us that the probability of counting multiple times the same bird increases as individuals repeatedly use the same sites on successive journeys and the turnover rate decreases. By systematically reporting cumulative counts as a reliable measure of waterbird abundance, ecological studies and conservation efforts might be misguided. We think that these problems could be prevented, or at least alleviated, by using species/assemblage maximum (peak) abundance data for the appropriate time periods.

Acknowledgements

To the company and help of our friends A. Berumen Solórzano, M. R. Maimone Celorio, C. I. Olivera Ávila and, specially, J. A. Villordo Galván during field work. The comments by 3 anonymous reviewers greatly helped to improve a previous version of our manuscript.

References

References

Agresti, A., & Franklin, C. (2013). Statistics. The art and science of learning from data. Boston: Pearson.

Alonso, J. C., Alonso, J. A., & Bautista, L. M. (1994). Carrying capacity of staging areas and facultative migration extension in common cranes. Journal of Applied Ecology, 31, 212–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/2404537

Amador, E., Mendoza-Salgado, R., & De Anda-Montañez, J. A. (2006). Estructura de la avifauna durante el período invierno-primavera en el estero Rancho Bueno, Baja California Sur, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 77, 251–259. https://10.22201/ib.20078706e.2006.002.340

Arizaga, J., Cepeda, X., Maguregi, J., Unamuno, E., Ajuriagogeaskoa, A., Borregón, L. et al. (2014). The influence of the creation of a lagoon on waterbird diversity in Urdaibai, Spain. Waterbirds, 37, 111–118. https://doi.org/10.1675/063.037.0115

Ayala-Pérez, V., Arce, N., & Carmona, R. (2013). Distribución espacio-temporal de aves acuáticas invernantes en la ciénega de Tláhuac, planicie lacustre de Chalco, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 84, 327–337. https://doi.org/10.7550/rmb.28632

Berumen-Solórzano, A., Maimone-Celorio, M. R., Villordo-Galván, J. A., Olivera-Ávila, C. I., & González-Oreja, J. A. (2017). Cambios temporales de la avifauna acuática en el sitio Ramsar “Presa de Valsequillo”, Puebla, México. Huitzil, 18, 202–211. https://doi.org/10.28947/hrmo.2017.18.2.278

British Ecological Society. (2015). A guide to getting published in ecology and evolution. London: British Ecological Society.

Buckland, S. T., Marsden, S. J., & Green, R. E. (2008). Estimating bird abundance: making methods work. Bird Conservation International, 18, S91–S108. https://10.1017/S0959270908000294

Conway, C. J. (2011). Standardized North American marsh bird monitoring protocol. Waterbirds, 34, 319–346. https://doi.org/10.1675/063.034.0307

Cui, P., Wu, Y., Ding, H., Cao, M., Chen, L., Chen, B. et al. (2014). Status of wintering waterbirds at selected locations in China. Waterbirds, 37, 402–409. https://10.1675/063.037.0407

Cupul-Magaña, F. B. (1997). La laguna El Quelele, Nayarit, México, como hábitat de aves acuáticas. Ciencia y Mar, 3, 21–28.

Cupul-Magaña, F. B. (2000). Aves acuáticas del estero El Salado, Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco. Huitzil, 1, 3–8. https://doi.org/10.28947/hrmo.2000.1.1.1

Devenish, C., Díaz-Fernández, D. F., Clay, R. P., Davidson, I., & Yépez-Zabala, I. (2009) (Eds.). Important bird areas: Americas – priority sites for biodiversity conservation (BirdLife Conservation Series No. 16). Quito: BirdLife International.

Eisermann, K., & Avendaño, C. (2009). Conservation priority-setting in Guatemala through the identification of important bird areas. In T. D. Rich, C. Arizmendi, D. W. Demarest, & C. Thompson (Eds.), Tundra to Tropics: connecting birds, habitats and people (pp. 315–327). Proceedings of the Fourth International Partners in Flight Conference. Partners in Flight, McAllen.

Elzinga, C. L., Salzer, D. W., Willoughby, J. W., & Gibbs, J. P. (2001). Monitoring plant and animal populations. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Science.

Fasham, M., & Mustoe, S. (2005). General principles and methods for species. In D. Hill, M. Fasham, G. Tucker, M. Shewry, & P. Shaw (Eds.), Handbook of biodiversity methods. Survey, evaluation and monitoring (pp. 255–270). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fonseca, J., Pérez-Crespo, M. J., Cruz, M., Porras, B., Hernández-Rodríguez, E., Martínez y Pérez, J. L. et al. (2012). Aves acuáticas de la laguna de Acuitlapilco, Tlaxcala, México. Huitzil, 13, 104–109. https://doi.org/10.28947/hrmo.2012.13.2.156

Frost, T. M., Austin, G. E., Calbrade, N. A., Mellan, H. J., Hearn, R. D., Robinson, A. E. et al. (2019). Waterbirds in the UK 2017/18: The Wetland Bird Survey. BTO/RSPB/JNCC. Thetford.

Gerardo-Tercero, C. M., Enríquez, P. L., & Rangel-Salazar, J. L. (2010). Diversidad de aves acuáticas en la laguna Pampa El Cabildo, Chiapas México. El canto del Cenzontle, 1, 33–48.

Gibbons, W. D., & Gregory, R. D. (2006). Birds. In W. J. Sutherland (Ed.), Ecological census techniques. 2nd Ed. (pp. 308–350) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gladon, R. J., Graves, W. R., & Kelly, J. M. (2011). Getting published in the Life Sciences. New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell. https://10.1002/9781118041673

Good, P. (2005). Permutation, parametric, and bootstrap tests of hypotheses. 3rd Ed. New York: Springer.

Gotelli, N. J., & Colwell, R. K. (2011). Estimating species richness. In A. E.Magurran, & B. J. McGill (Eds.), Biological diversity. Frontiers in measurement and analysis (pp. 39–54). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gotelli, N. J., & Ellison, A. M. (2013). A primer of ecological statistics. 2nd Ed. Sunderland: Sinauer.

Gray, M. J., Chamberlain, M. J., Buehler, D. A., & Sutton, W. B. (2013). Wetland wildlife monitoring and assessment. In J. T. Anderson, & C. A. Davis (Eds.), Wetland techniques. Vol. 2, Organisms (pp.265–318). New York: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6931-1_7

Greenwood, J. J. D., & Gibbons, D. (2008). Why counting is so important and where to start. In P. Voříšek, A. Klvaňová, S. Wotton, & R. D. Gregory (Eds.), A best practice guide for wild bird monitoring schemes (pp. 10–20). Třeboň: CSO/RSPB.

Greenwood, J. J. D., & Robinson, R. A. (2006). Principles of sampling. In W. J. Sutherland (Ed.), Ecological census techniques. 2nd Ed. (pp. 11–86). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gregory, R. D., Gibbons, D. W., & Donald, P. F. (2004). Bird census and survey techniques. In W. J. Sutherland, I. Newton, & R. E. Green (Eds.), Bird ecology and conservation. A handbook of techniques (pp.17–55). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Guzmán, J., Carmona, R., Bojórquez, M., & Palacios, E. (1994). Distribución temporal de aves acuáticas en el estero de San José del Cabo, B.C.S, México. Ciencias Marinas, 20, 93–103.

Hammer, Ø. (2018). PAST Vers. 3.22 Reference manual. Oslo: Natural History Museum.

Henderson, P. A. (2003). Practical methods in ecology. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Science.

Hernández-Colina, A., Yadeun, M., & García-Espinosa, G. (2018). Waterfowl community from a protected artificial wetland in Mexico State, Mexico. Huitzil, 19, 85–95. https://doi.org/10.28947/hrmo.2018.19.1.310

Hernández-Vázquez, S. (2000). Aves acuáticas del estero La Manzanilla, Jalisco, México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (nueva serie), 80, 143–153.

Hernández-Vázquez, S. (2005). Aves acuáticas de la Laguna de Agua Dulce y el Estero El Ermitaño, Jalisco, México. Revista de Biología Tropical, 53, 229–238. https://10.15517/rbt.v53i3-4.33118

Hurlbert, S. H. (1984). Pseudoreplication and the design of ecological field experiments. Ecological Monographs, 54, 187–211. https://doi.org/10.2307/1942661

Isotti, R., Battisti, C., & Luiselli, L. (2015). Seasonal and habitat-related changes in bird assemblage structure: applying a diversity/dominance approach to Mediterranean forests and wetlands. Israel Journal of Ecology, & Evolution, 61, 28–36. https://10.1080/15659801.2015.1031463

Johnson, D. H. (2008). In defense of indices: the case of bird surveys. Journal of Wildlife Management, 72, 857–868. https://doi.org/10.2193/2007-294

Jones, M. (2000). Study design. In C. Bibby, M. Jones, & S. Marsden (Eds.), Expedition field techniques. Bird Surveys (pp. 14–34). Cambridge: BirdLife International.

Lloyd, H., Cahill, A., Jones, M., & Marsden, S. (2000). Estimating bird densities using distance sampling. . In C. Bibby, M. Jones, & S. Marsden (Eds.), Expedition field techniques. Bird Surveys (pp. 34–51). Cambridge: BirdLife International.

MacKenzie, D. I., Nichols, J. D., Royle, J. A., Pollock, K. H., Bailey, L. L., & Hines, J. E. (2018). Occupancy estimation and modeling: inferring patterns and dynamics of species occurrence. 2nd Ed. London: Academic Press.

Martínez-Curci, N. S., Isacch, J. P., & Azpiroz, A. B. (2015). Shorebird seasonal abundance and habitat-use patterns in Punta Rasa, Samborombón Bay, Argentina. Waterbirds, 38, 68–76. https://doi.org/10.1675/063.038.0109

McComb, B., Zuckergerg, B., Vesely, D., & Jordan, C. (2010). Monitoring animal populations and their habitats. A practitioner’s guide. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Mellink, E., & De la Riva, G. (2005). Non-breeding waterbirds at Laguna de Cuyutlán and its associated wetlands, Colima, Mexico. Journal of Field Ornithology, 76, 158–167. https://doi.org/10.1648/0273-8570-76.2.158

Mera-Ortiz, G., Ruiz-Campos, G., Gómez-González, A. E., & Velázquez-Velázquez, E. (2016). Composición y abundancia estacional de aves acuáticas en tres paisajes de la laguna Mar Muerto, Oaxaca-Chiapas. Huitzil, 17, 251–261. https://doi.org/10.28947/hrmo.2016.17.2.255

Millenium Ecosystem Assessment (2005). Ecosystems and human well-being: wetlands and water synthesis. Washington D.C.: World Resources Institute.

Molina, D., Cavitt, J., Carmona, R., & Cruz-Nieto, M. (2018). Non-breeding distribution, density and population structure of American Avocet (Recurvirostra americana, Gmelin 1789) in Marismas Nacionales, Nayarit, Mexico. Huitzil, 19, 22–32. https://doi.org/10.28947/hrmo.2018.19.1.308

Munguía, P., López, P., & Fortes, I. (2005). Seasonal changes in waterbird habitat and occurrence in Laguna de Sayula, Western Mexico. The Southwestern Naturalist, 50, 318–322. https://10.1894/0038-4909(2005)050[0318:SCIWHA]2.0.CO;2

Mustoe, S., Hill, D., Frost, D., & Tucker, G. (2005). Birds. In D. Hill, M. Fasham, G. Tucker, M. Shewry, & P. Shaw (Eds.), Handbook of biodiversity methods. Survey, evaluation and monitoring (pp. 412–432). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Newton, I. (2010). The migration ecology of birds. London: Academic Press.

Nur, N., Jones, S. L., & Geupel, G. R. (1999). Statistical guide to data analysis of avian monitoring programs. Biol. Tech. Pub. BTP-R6001-1999. Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service.

Prosser, D. J., Nagel, J. L., Marbán, P. R., Ze, L., Day, D. D., & Erwin, R. M. (2017). Standardization and application of an index of community integrity for waterbirds in the Chesapeake Bay, USA. Waterbirds, 40, 233–251. https://doi.org/10.1675/063.040.0305

Quinn, G. P., & Keough, M. J. (2002). Experimental design and data analysis for biologists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ramsar Convention Secretariat. (2010). Designating Ramsar sites. Strategic framework and guidelines for the future development of the List of Wetlands of International Importance. 4th Ed. Gland, Switzerland: Ramsar Convention Secretariat.

Rappole, J. H. (2013). The avian migrant. The biology of bird migration. New York: Columbia University Press.

Rosemberg, K. V., Dokter, A. M., Blancher, P. J., Sauer, J. R., Smith, A. C., Smith, P. A. et al. (2019). Decline of the North America avifauna. Science, 366, 120–124. https://10.1126/science.aaw1313

Russell, I. A., Randall, R. M., & Hanekom, N. (2014). Spatial and temporal patterns of waterbird assemblages in the Wilderness Lakes Complex, South Africa. Waterbirds, 37, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1675/063.037.0104

Sánchez-Bon, G., Fernández, G., Escobedo-Urías, D., Torres-Torner, J., & Cid-Becerra, J. A. (2010). Spatial and temporal composition of the avifauna from the barrier islands of the San Ignacio-Navachiste-Macapule lagoon complex, Sinaloa, Mexico. Ciencias Marinas, 36, 355–370. https://10.7773/cm.v36i4.1683

Shuter, J. L., Broderick, A. C., Agnew, D. J., Jonzen, N., Godley, B. J., Milner-Gulland, E. J. et al. (2011). Conservation and management of migratory species. In E. J. Milner-Gulland, J. M. Fryxell, & A. R. E. Sinclair (Eds.), Animal migration. A synthesis (pp. 172–206). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Smith, M. A., Walker, N. J., Free, C. M., Kirchoff, M. J., Drew, G. S., Warnock, N. et al. (2014). Identifying marine important bird areas using at-sea survey data. Biological Conservation, 172, 180–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.02.039

Southwood, T. R. E., & Henderson, P. A. (2016). Ecological methods. 4th Ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science.

Thompson, W. L., White, G. C., & Gowan, C. (1998). Monitoring vertebrate populations. San Diego: Academic Press.

Valle, S., Boitani, L., & Maclean, I. M. D. (2014). Seasonal changes in abundances of waterbirds at Sabaki River Mouth (Malindi, Kenya), a key stopover site on the West Asian-East African Flyway. Ostrich, 83, 19–26. https://doi.org/10.2989/00306525.2012.680262

Van der Valk, A. G. (2012). The biology of freshwater wetlands. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vega, X., González, M. A., & Muñoz-del Viejo, A. (2006). Potential new Ramsar sites in northwest Mexico: strategic importance for migratory waterbirds and threats to conservation. In G. C. Boere, C. A. Galbraith, & D. A. Stroud (Eds.), Waterbirds around the World. (pp. 158–160). Edinburgh: The Stationery Office.

Weller, M. W. (2004). Wetland birds. Habitat resources and conservation implications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wetlands International. (2010). State of the World’s waterbirds 2010. Ede, The Netherlands: Wetlands International.

Wilson, S., Bazin, R., Calvert, W., Doyle, T. J., Earsonm, S. D., Oswald, S. A. et al. (2014). Abundance and trends of colonial waterbirds on the Large Lakes of Southern Manitoba. Waterbirds, 37, 233–247. https://doi.org/10.1675/063.037.0302

Zárate-Ovando, B., Palacios, E., Reyes-Bonilia, H., Amador, E., & Saad, G. (2006). Waterbirds of the lagoon complex Magdalena Bay-Almejas, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Waterbirds, 29, 350–364. https://doi.org/10.1675/1524-4695(2006)29[350:WOTLCM]2.0.CO;2

Zӧckler, C., Beresford, A. E., Bunting, G., Chowdhury, S. U., Clark, N. A., Kan Fu, V. W. et al. (2016). The winter distribution of the Spoon-billed Sandpiper Calidris pygmaeus. Bird Conservation International, 26, 476–489. https://10.1017/S0959270915000295