Berenice Núñez-López a, Francisco Alberto Rivera-Ortíz b, *, Carlos Alberto Soberanes-González a, María del Coro Arizmendi a

a Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala, Unidad de Biotecnología y Prototipos, Laboratorio de Ecología, Avenida de los Barrios Núm. 1, Los Reyes Ixtacala, 54090 Tlalnepantla, Estado de México, Mexico

b Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala, Unidad de Biotecnología y Prototipos, Laboratorio de Ecología Molecular y Evolución, Avenida de los Barrios Núm. 1, Los Reyes Ixtacala, 54090 Tlalnepantla, Estado de México, Mexico

*Corresponding author: francisco.rivera@iztacala.unam.mx (F.A. Rivera-Ortíz)

Received: 23 December 2019; accepted: 16 December 2020

Abstract

The Military Macaw (Ara militaris) is an endangered species with scarce available information on its natural history. One of the main problems regarding its study has been the identification of individuals, which rapidly reach adult size and lack sexual dimorphism. Traditional marking techniques used to identify individuals require their capture; however, there is a high risk of injury. Also, marking can influence behavior, reproduction, and survival, so there is a high probability of disturbing the population. To minimize such disturbances, it is advisable to use natural markings to identify individuals. Photo-identification is one marking technique that can help to identify individuals without disturbing populations. In the case of the Military Macaw, the face lines (feather patterns) present natural marks that can be used for the photo-identification of individuals using specialized software. In this study, we tested the utility (effectiveness) of photo-identification in 24 Military Macaw individuals in captivity. Significant differences were found between the feather patterns on the right and left sides of the face of the same individual and also between the feather patterns on the right and left sides among individuals. We propose here that photo-identification is a reliable technique for distinguishing Military Macaws individuals within a population, opening the door to more specific ecological studies.

Keywords: Feather patterns; Photo-identification; Military Macaw, Natural markings

Diferenciación de guacamayas verdes (Ara militaris) en cautiverio usando la foto-identificación

Resumen

La guacamaya verde (Ara militaris) es una especie en peligro de extinción con escasa información disponible sobre su historia natural. Uno de los principales problemas con respecto a su estudio ha sido la identificación de individuos, que alcanzan rápidamente el tamaño adulto y carecen de dimorfismo sexual. Las técnicas de marcado tradicionales utilizadas para identificar individuos requieren su captura; sin embargo, existe un alto riesgo de lesiones. Además, el marcado puede influir en el comportamiento, la reproducción y la supervivencia, por lo que hay una alta probabilidad de perturbar a la población. Para minimizar tales perturbaciones, es aconsejable utilizar marcas naturales para identificar a los individuos. La fotoidentificación es una técnica de marcado que puede ayudar sin perturbar a las poblaciones. En el caso de la guacamaya verde, las líneas de la cara (patrones de plumas) presentan marcas naturales que pueden usarse para la fotoidentificación de individuos, utilizando software especializado. En el presente estudio probamos la utilidad (efectividad) de la fotoidentificación en 24 individuos en cautiverio. Se encontraron diferencias significativas entre los patrones de plumas en los lados derecho e izquierdo de la cara del mismo individuo y también entre los patrones de plumas en los lados derecho e izquierdo entre los individuos. Proponemos que la fotoidentificación para las guacamayas verdes es una técnica confiable para distinguir a los individuos dentro de una población, abriendo la puerta a estudios ecológicos más específicos.

Palabras clave: Patrones de plumas; Fotoidentificación; Guacamaya verde; Marcas naturales

© 2021 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. Este es un artículo Open Access bajo la licencia CC BY-NC-ND

Introduction

Estimates of population size and life history are critical to effectively manage wildlife (Caughley, 1994). A basic requirement for many ecological and conservation studies is the identification of the individuals within a population (Bradshaw et al., 2007; Lusseau et al., 2006; McMahon et al., 2007; Schofield et al., 2008). Most studies on animal populations depend on different marking techniques to identify individuals. Highly utilized methods include permanent marks (tattoos and scissions), semi-permanent marks (tags, rings, necklaces, and belts), and temporary marks (fluorescent powders, paint marks, etc.) (McMahon et al., 2007; Sélem et al., 2004; Schofield et al., 2008).

Most of these marking techniques require the capture of organisms. However, capture involves risk of injury, and marking may influence the behavior, reproduction, or survival of the individuals in a population (Dugger et al., 2006; Nichols & Seminoff, 1998; Sélem et al., 2004). Furthermore, identification marks can fall off or disappear, which can interrupt the continuity of long-term studies (Limpus et al., 1992; Sibly et al., 2005; Schofield et al., 2008).

To minimize these disturbances, it is recommended to use automatic marking devices or natural markings for identification of individuals, especially when individuals are difficult to capture or mark (Beck & Osborn, 1995; Renton, 2004). Many individuals can be naturally identified by their markings or color patterns, scars, and lack or presence of a flight feather, among others (Best et al., 1993; Renton, 2004; Sélem et al., 2004). Together, these characteristics in each individual may form a unique pattern, known as a fingerprint, which allows individuals to be recognized on subsequent occasions. This identification technique represents one alternative to the capture-recapture method (Gamble et al., 2008).

The photo-identification by visual interpretation method consists in photographing individuals and identifying them according to individual natural markings. Individuals may be subsequently re-identified based on the visual correspondence of natural markings and patterns in the photographs. This method is capable of capturing the necessary details for distinguishing individuals (Gamble et al., 2008), and it has been already proven to be a useful tool in the long-term monitoring of several wildlife populations (Beck & Reid, 1995; Bradshaw et al., 2007; Thompson et al., 2000), such as in the study of marine mammals, in which identification is based on patterns of spots on their bodies (Acevedo et al., 2006; Calambokidis et al., 2009; Cañadas & Sagarminaga, 1995; Constantine et al., 2007; Glockner & Venus, 1983; Martínez-Aguilar, 2008; Valdes-Arellanes et al., 2011; Vigness-Raposa et al., 2010). In some terrestrial mammals, the identification is based on patterns of spots, lines, scars, and even behavior (Caro, 1994; Foster, 1996; Goodall, 1986; Kelly, 2001; Masclans, 2010; Reynolds et al., 2005).

Photo-identification based on specialized software has been little used for bird identification (Arroyo & Bretagnolle, 1999; Bretagnolle et al., 1994; Munn, 2012; Renton, 2004), therefore relying on visual interpretation for individual recognition. In these cases, identification has been based on distinguishing marks, such as plumage patterns, and specific individual coloration (e.g., eye rings, crown, eyebrows, tail feathers, primary and secondary feathers). In a couple of cases, Renton (2004) and Munn (2012) identified individuals of the Blue-Yellow Macaw (Ara ararauna) and Green-Winged Macaw (Ara chloroptera), respectively, in the field based on facial feather lines and the auricular area.

Although photo-identification by visual interpretation has been explored in a few bird species, the usefulness of this method using specialized software for the bio-monitoring of bird species lacking sexual dimorphism has not yet been explored; moreover, these bird species generally have a lengthy longevity, and young individuals reach their adult size quickly therefore hindering the determination of different ecological and biological aspects, as is the case for macaws (genus Ara).

The Military Macaw (Ara militaris) is included in the Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES, 1998), and is considered as globally vulnerable by International Union for Conservation of Nature (BirdLife International, 2020). In Mexico, the species is enlisted as endangered (Norma Oficial Mexicana, NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010) (Semarnat, 2010), due to the destruction of its habitat and its capture for illegal trade (Íñigo-Elías, 2000). The Military Macaw has a disjunct distribution ranging from Mexico to northern Bolivia (Forshaw, 1989; Íñigo-Elías, 1999; Peterson & Chaliff, 1989). In Mexico, its historic distribution included the Pacific and Gulf slopes (Peterson & Chaliff, 1989; Ridgway, 1915; Rivera-Ortíz et al., 2013), inhabiting tropical deciduous, semi-deciduous, and pine-oak forests in lowland areas (Arizmendi & Márquez-Valdelamar, 2000; Carreón, 1997; Collar, 1997; Forshaw, 1989; Juniper & Parr, 1998).

Studies on Military Macaw populations in Mexico have mainly addressed natural history and aspects related to food preferences, reproduction, distribution, and population genetics (Carreón, 1997; Contreras-González et al., 2009; Gaucin et al., 1999; Loza, 1997; Rubio et al., 2007; Rivera-Ortiz et al., 2008, 2013, 2016). Although recent studies have provided valuable information, it is necessary to carry out more detailed studies on the behavior, reproductive biology, birth and mortality rates, and temporary spatial movements, among other aspects, which would require the identification of individuals. Therefore, we here tested the effectiveness of photo-identification based on specialized software as a technique for differentiating and recognizing captive Military Macaw individuals. We hope that our results provide a basis for the future recognition of Military Macaw individuals in wild populations.

Materials and methods

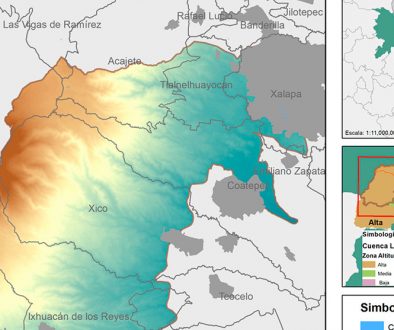

We consulted the database of Management Units for the Conservation of Wildlife (UMAs for its initials in Spanish) of the Mexican government to identify which UMA had a fair and manageable number of individuals of Military Macaws, and we selected the captive population at the Africam Safari Zoo in Puebla, Mexico. Military Macaws at this site are trained by specialized personnel, who helped in taking photographs. Also, the population at this site is likely heterogeneous, comprising more than 100 individuals of unknown geographical origin that have been recovered from illegal trafficking activities in the country (Núñez-López, 2014).

Twenty-four trained and highly manageable macaws were selected, which facilitated taking the photographs. Two photography sessions were held for each individual: one for each side of the face. Ten lateral pictures of each side were taken with a Nikon D60 camera using an 18-55 mm focal length lens, a F of 5.6, and an ISO of 200. The photographs were taken at a distance of 2 meters using a tripod (Fig. 1A). During the sessions, the following data were also recorded for each individual: i) number of rings (individual metal rings with a unique number for bird identification), ii) sex, iii) age, iv) number of photographs, and v) side of the face (Supplementary material, Appendix 1). The number of rings identified the individual during photoshoots.

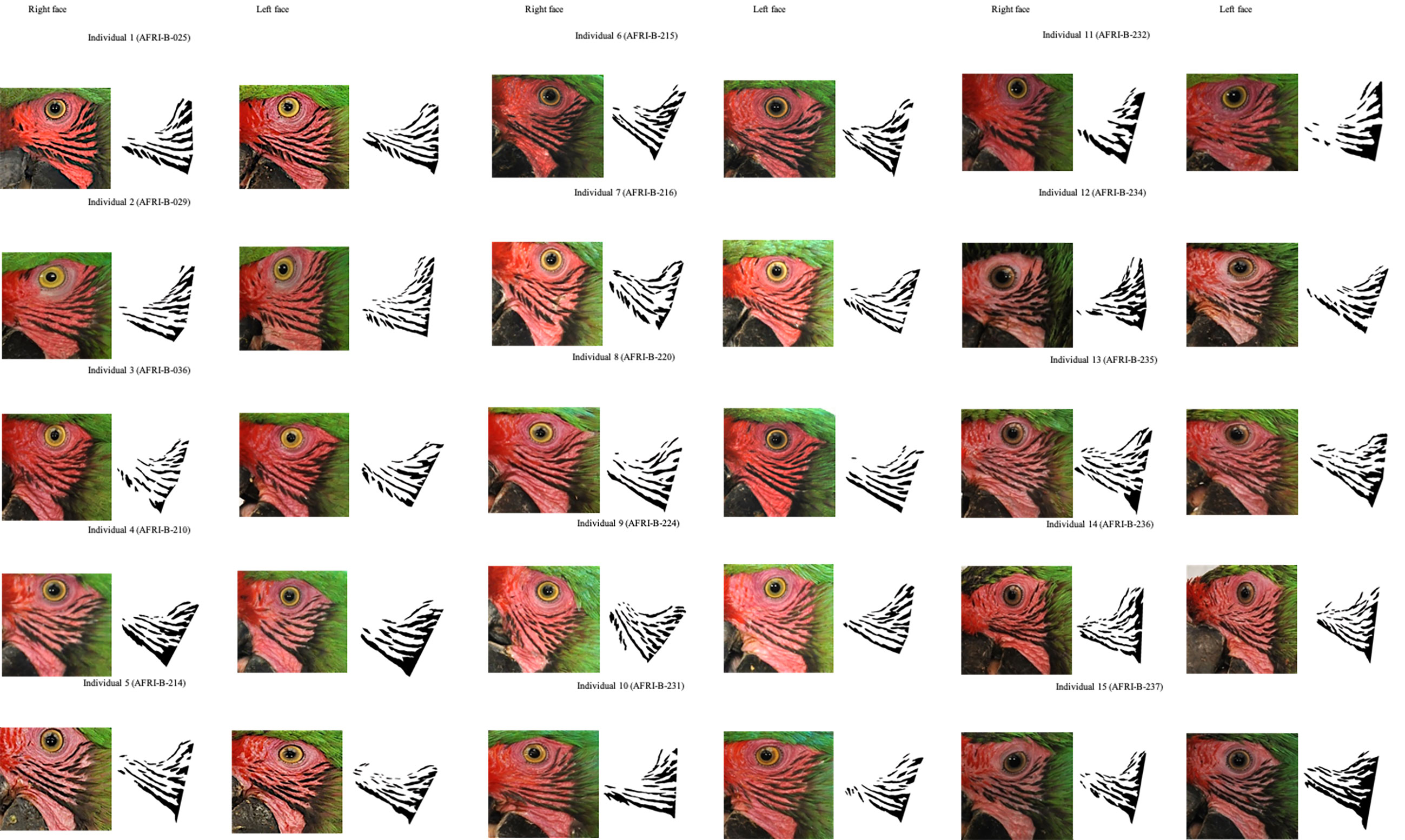

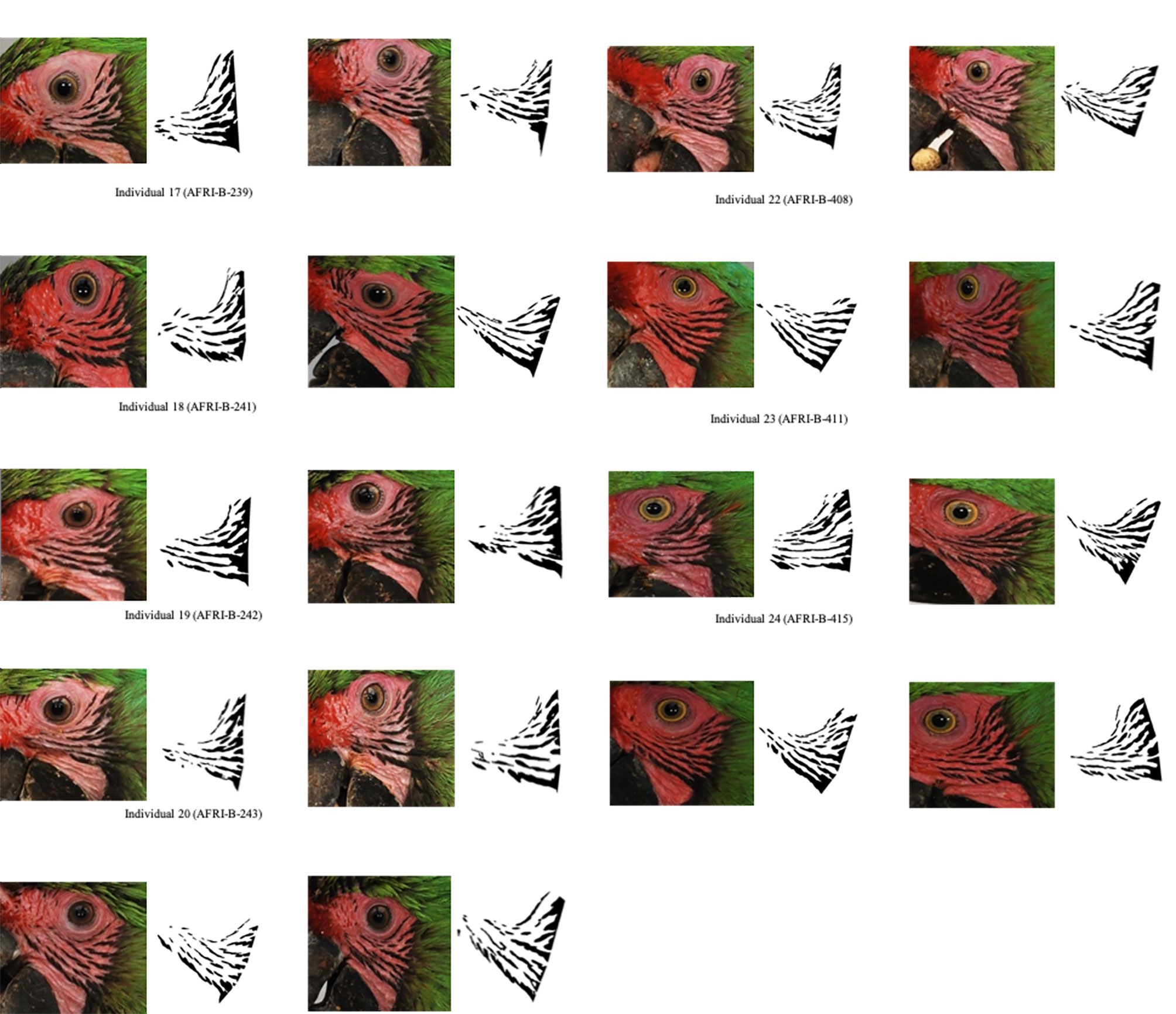

To have a complete and defined view of the face feathers, we reframed all photographs to include only the face area of each of the macaws (Fig. 1B), in which the natural markings formed by the feathers in the cheeks form a unique pattern of black lines (hereafter feather pattern), which was isolated for further analysis (Fig. 1C). The size of the photographs was 750 × 750 pixels, which is required to input the photographs into SISREC 1.0 for the automatic recognition of images (Padilla-Ramírez, 2012).

Using ADOBE PHOTOSHOP CS6, we recovered these feather patterns as follows: i) for each individual, feather patterns on the right and left sides of the face were selected from the original photograph using the magic wand tool (Fig. 1B); ii) based on the orientation and size, feather patterns of all individuals were homogenized by cutting to show only feathers patterns; iii) then, the investment color tool was used to fill the background (as white), leaving only the black feather patterns of the face (Fig. 1C), and iv) final images were saved in .bmp format.

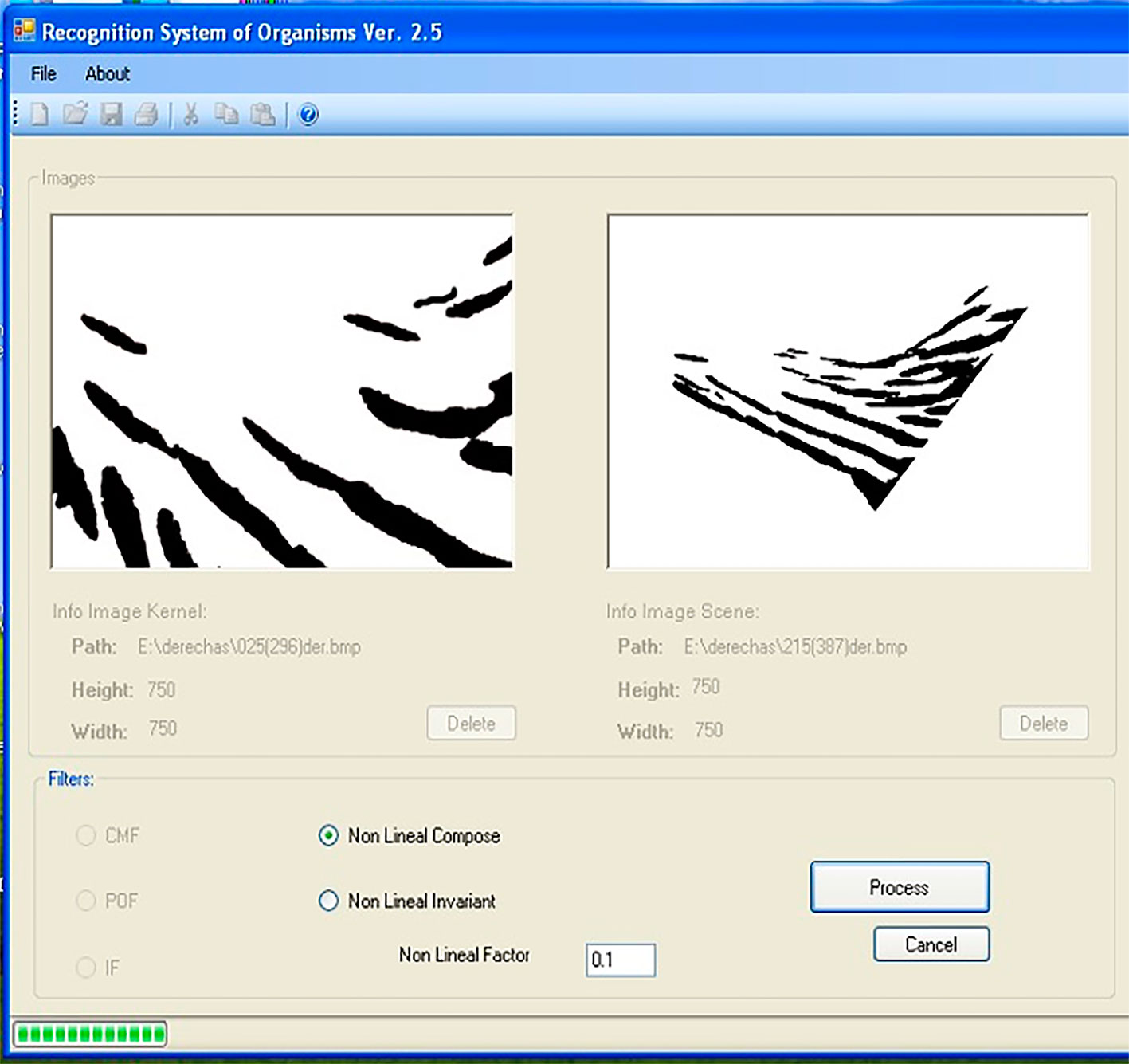

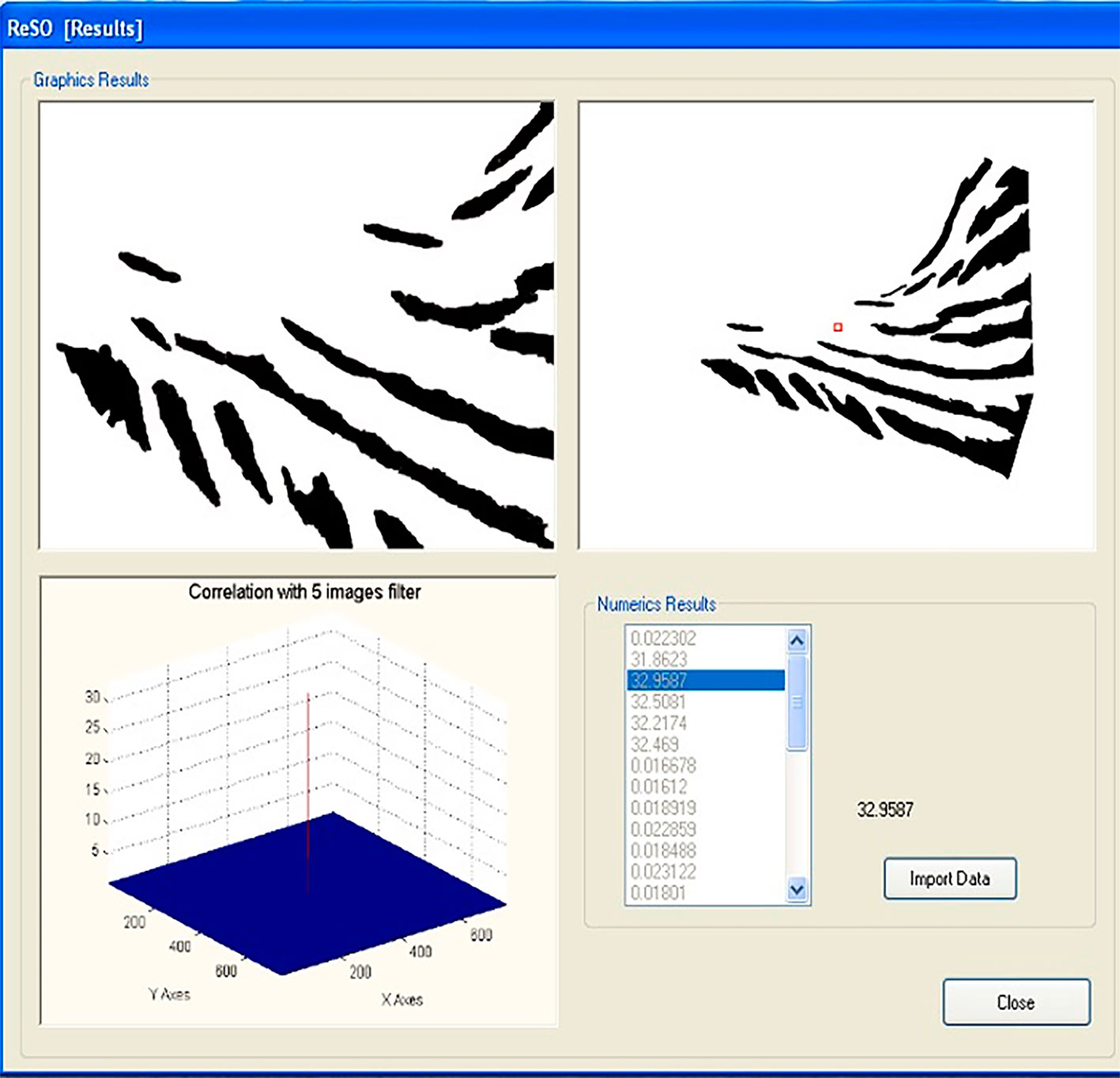

We used SISREC 1.0 to perform the automatic recognition of macaw individuals based on an automatic correlation procedure that minimizes the time required for manual recognition at a high reliability (> 90%). SISREC 1.0 manages a compact and simple interface, making identification easy and simple (Padilla-Ramírez, 2012). Figure 2 shows the main screen of the program, where the user loads the filter image (kernel), problem images (scene) and the type of filter to use. In particular, this software uses a filter image for the comparison created from a minimum of 5 different images of the same side of the face of the same individual (Padilla-Ramírez, 2012). The filter image is placed in the window on the left side; in the right window are placed scene images of all individuals to be compared, including those used as filter images (Fig. 2). Images are then processed by the program using a non-linear filter with a level of k = 0.1. A non-linear filter was used because several images were combined to generate the control image. Also, it can be optimized to achieve lower sensitivity to scale, rotation, and lighting of all images used (Guerrero-Moreno & Álvarez-Borrego, 2009). The resultant screen (Fig. 3), shows the correlation between images in the form of a three-dimensional graph where the location of the maximum peak of the correlation of each image is observed, with the option to import for calculations statistics (Padilla-Ramírez, 2012).

The obtained data were analyzed using non-parametric tests, since these were not normal distributed. First, for all 24 individuals, we compared the images of the feather patterns of the right side of the face with those of the left side of the face of the same individual. We used a Wilcoxon-T test adjusted with a Bonferroni correction to identify whether the right and left feather patterns of the face of the same individual were identical or different. This test evaluates the probability that the differences found between 2 related samples are due solely to the sampling error from the comparison of pairs and has the advantage that it gives more weight to the larger differences (Zar, 1999). Then, the images of both sides of the face were compared to those of the remaining 23 individuals. This same procedure was performed for all individuals. We then used a Friedman Q test adjusted to a Bonferroni correction to determine whether there were differences in the facial feather patterns (on the right and left sides of the face) among the 24 individuals. This test compares 3 or more related samples and determines that the differences found are not due to randomness (Zar, 1999). All statistical tests were carried out in Statistica 6 (www.statsoftiberica.com; StatSoft Inc., 1984).

Results

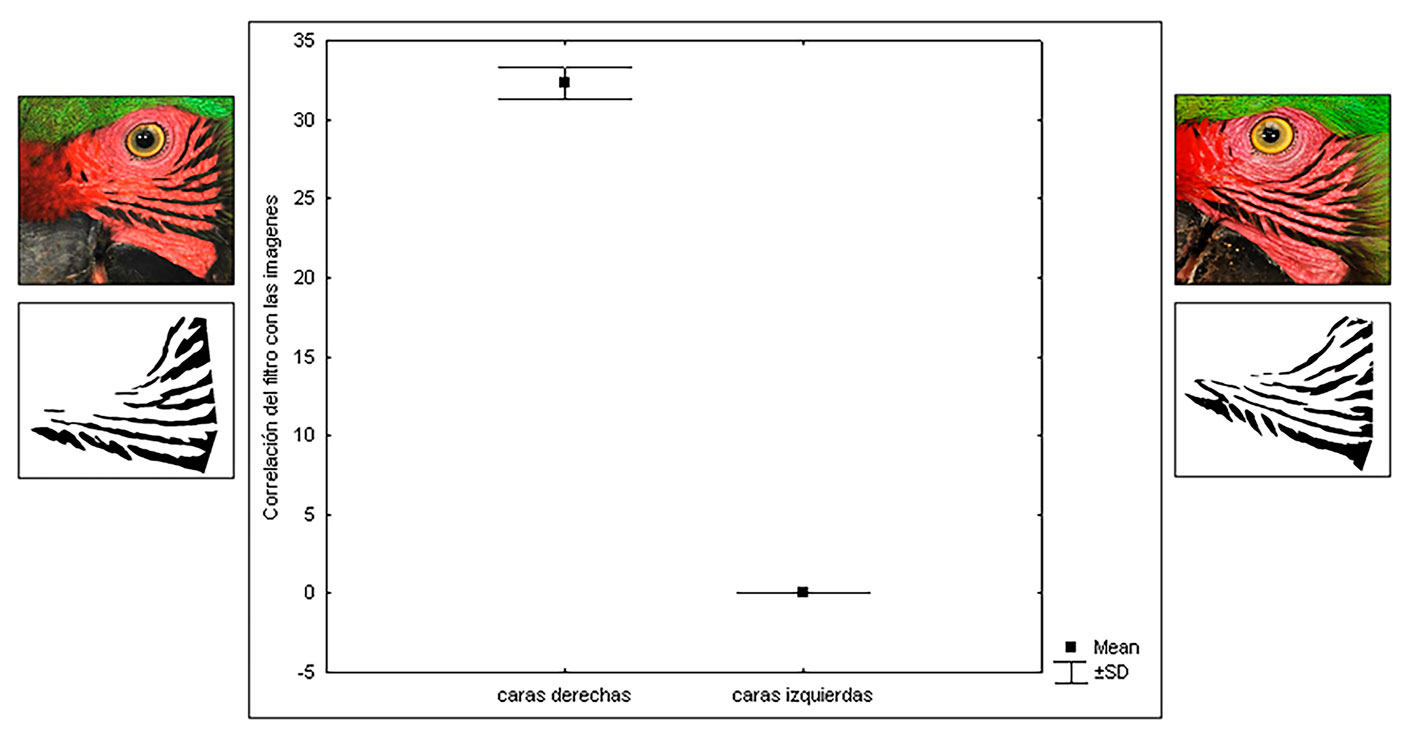

A total of 240 photographs (10 photographs per individual, 5 photographs of each side of the face) of the facial feather patterns of 24 Military Macaw individuals were taken. We found that the patterns of the feathers on the right side of the face (32 ± 1.5 maximum correlation) are significantly different from these on the left side of the face (0.5 ± 0.03 maximum correlation), in each individual (Fig. 4). These differences were consistent in all 24 analyzed individuals (Table 1).

Significant differences were also found in the feather pattern of the right side of the face of each individual with respect to that of all other macaws, as well as in the feather pattern of the left side of the face of each individual with respect to that of all other macaws. These findings indicate that the facial feather patterns of Military Macaws are not identical among individuals (Table 2). Differences in the right and left side of the face are shown for all individual Military Macaws (Supplementary material, Appendix 2).

Table 1

Significant differences in the feather’s patterns of the right side versus the left side of the face in each Military Macaw individual based on the Wilcoxon T test with the Bonferroni correction. T = Wilcoxon T test; * Bonferroni correction (PBC) p < 0.05.

| Number of individuals | Band number | Right side vs. left side | |

| T | PBC | ||

| 1 | AFRI-B-025 | 9.5061 | 0.0002* |

| 2 | AFRI-B-O29 | 2.0041 | 0.0001* |

| 3 | AFRI-B-036 | 7.5268 | 0.0004* |

| 4 | AFRI-B-210 | 9.5301 | 0.0002* |

| 5 | AFRI-B-214 | 5.2035 | 0.0003* |

| 6 | AFRI-B-215 | 8.5960 | 0.0001* |

| 7 | AFRI-B-216 | 4.0069 | 0.0002* |

| 8 | AFRI-B-220 | 7.2640 | 0.0002* |

| 9 | AFRI-B-224 | 4.5061 | 0.0006* |

| 10 | AFRI-B-231 | 5.4480 | 0.0004* |

| 11 | AFRI-B-232 | 4.5920 | 0.0001* |

| 12 | AFRI-B-234 | 9.0023 | 0.0009* |

| 13 | AFRI-B-235 | 9.5061 | 0.0007* |

| 14 | AFRI-B-236 | 6.5040 | 0.0002* |

| 15 | AFRI-B-237 | 8.0580 | 0.0001* |

| 16 | AFRI-B-238 | 9.4640 | 0.0005* |

| 17 | AFRI-B-239 | 5.2416 | 0.0002* |

| 18 | AFRI-B-241 | 6.8032 | 0.0008* |

| 19 | AFRI-B-242 | 7.6069 | 0.0010* |

| 20 | AFRI-B-243 | 5.4750 | 0.0009* |

| 21 | AFRI-B-244 | 6.7261 | 0.0003* |

| 22 | AFRI-B-408 | 6.1556 | 0.0002* |

| 23 | AFRI-B-411 | 8.0368 | 0.0001* |

| 24 | AFRI-B-415 | 9.0865 | 0.0002* |

Discussion

Several studies have shown that photo-identification based on natural markings is useful for identifying individuals of species with similar phenotypic characteristics, which allows generating more accurate demographic or migratory information (Bretagnolle et al., 1994; Connolly et al., 2002; De Oliveira & Rosso, 2008; Forcada & Aguilar, 2000; Foster, 1966; Foster et al., 2006; Gamble et al., 2008; Mizroch et al., 2004; Peterson, 1972; Reynolds et al., 2005; Valdes-Arellanes et al., 2011). In addition, this technique represents an alternative to traditional marking methods, because it does not require the physical capture of animals, thereby preventing stress. It is non-invasive, inexpensive, and as our study shows, it may be reliable, and might potentially be used in long-term studies or monitoring. Photo-identification could be particularly suitable for species of conservation concern, both in captivity and wildlife (Buonantony, 2008). In the case of species in wildlife, to generate the photographic catalogue and use this technique, the first thing to take into account is to have information on the ecology of the species, locate feeding, rest or sleeping areas, know the daily activity, etc. Second, identify areas where more individuals congregate, and that the photographic sample can be taken without disturbances. Third, have the professional help of a photographer and photographic equipment that allows taking the details of the natural marks (Dixon, 2003; Masclans, 2010; Trujillo-González, 1994).

Although photo-identification of natural markings is a promising technique, it still relies on visual interpretation, and processing of large amounts of data can be labor intensive and highly subject to human error. Also, the accuracy and reliability of photographic comparisons can be hampered by low image quality (light intensity and clarity), and the size of the database (Schofield et al., 2008). On the other hand, a higher number of photographs per individual would also increase the reliability in photo-identification results by visual interpretation. However, this technique is useful for the identification of Military Macaws only if the photographs are of good quality and clearly show the feathers patterns of the face. One alternative to reduce human error in photo-identification by visual interpretation is the use of specialized software for pattern recognition, as in our study. An additional benefit of software use is that it provides different tools for more effective, automatic, or fast identification (Kelly, 2001; Padilla-Ramírez, 2012).

In the case of birds, natural markings have previously been used to visually differentiate individuals (Munn, 2012; Renton, 2004). In this study with Military Macaw, we considered the feather patterns on its face. Our findings showed that facial lines form unique feather patterns allowing for individual recognition, moreover, these differences can be observed visually and statistically characterized. These findings underscore photo-identification as a useful technique for identifying gregarious species such as the Military Macaw, where it may be nearly impossible to identify individuals, especially considering that there are no noticeable visible differences between males and females, or between young and adult individuals (Íñigo-Elías, 1999). Demographic studies of such species would be more accurate and reliable if their life histories could be closely tracked, including individual seasonal movements and habitat use (Foote et al., 2009; Mackey et al., 2007).

Table 2

Significant differences in the feather patterns of the right side and left side of the face in 24 Military Macaws based on the Friedman Q test with the Bonferroni correction. *Bonferroni correction (PBC) p < 0.05. Q = Friedman Q test.

| Number of Individuals | Band number | Right faces | Left faces | ||

| Q 5,23 | PCB | Q 5,23 | PCB | ||

| 1 | AFRI-B-025 | 52.9680 | 1.6E-05* | 50.1680 | 0.0000* |

| 2 | AFRI-B-O29 | 35.0400 | 0.0023* | 63.2800 | 4.5E-07* |

| 3 | AFRI-B-036 | 44.2658 | 0.0002* | 52.7600 | 1.8E-05* |

| 4 | AFRI-B-210 | 53.3520 | 0.0001* | 52.4025 | 0.0002* |

| 5 | AFRI-B-214 | 47.2480 | 0.0009* | 50.3120 | 3.8E-05* |

| 6 | AFRI-B-215 | 34.9600 | 0.0023* | 44.6000 | 0.0002* |

| 7 | AFRI-B-216 | 48.5920 | 6.4E-05* | 54.9360 | 9.0E-06* |

| 8 | AFRI-B-220 | 41.4480 | 0.0004* | 50.4640 | 3.6E-05* |

| 9 | AFRI-B-224 | 55.2640 | 8.1E-06* | 57.5200 | 4.0E-06* |

| 10 | AFRI-B-231 | 40.7520 | 0.0005* | 59.8400 | 1.8E-06* |

| 11 | AFRI-B-232 | 42.9920 | 0.0003* | 53.5920 | 1.3E-05* |

| 12 | AFRI-B-234 | 49.8863 | 4.3E-05* | 47.0000 | 0.0001* |

| 13 | AFRI-B-235 | 41.9040 | 0.0004* | 60.4880 | 1.3E-06* |

| 14 | AFRI-B-236 | 56.8080 | 0.0005* | 54.1120 | 1.1E-05* |

| 15 | AFRI-B-237 | 48.8880 | 5.8E-05* | 54.0640 | 1.1E-05* |

| 16 | AFRI-B-238 | 59.3920 | 2.2E-06* | 62.4640 | 9.0E-07* |

| 17 | AFRI-B-239 | 45.1600 | 0.0001* | 51.2480 | 2.8E-05* |

| 18 | AFRI-B-241 | 62.2400 | 9.0E-07* | 51.3280 | 2.8E-05* |

| 19 | AFRI-B-242 | 70.5920 | 0.0000* | 62.8960 | 4.5E-07* |

| 20 | AFRI-B-243 | 53.4720 | 1.4E-05* | 50.2320 | 3.9E-05* |

| 21 | AFRI-B-244 | 56.7360 | 0.0005* | 62.4954 | 9.0E-07* |

| 22 | AFRI-B-408 | 56.4720 | 5.4E-06* | 45.1440 | 0.0001* |

| 23 | AFRI-B-411 | 47.3680 | 9.1E-05* | 58.1200 | 3.1E-06* |

| 24 | AFRI-B-415 | 31.6560 | 0.0048* | 61.0800 | 1.3E-06* |

In conclusion, the utility of the photo-identification technique for identifying Military Macaws opens the door to more specific and reliable studies in wild populations that require individuals to be distinguished. This information will help to implement this technique in wild populations. It must also be taken into account that when implementing this technique in wild populations, determining the time of the molt is essential, since the results may vary. It has been documented that Psittaciformes have complete annual (small species) or biannual (larger species) molts and usually before the reproductive season (Durán, 2003), so the photo shoot must be made in the reproductive season, when the macaws have completed their molting cycle. Other limitations of photo-identification should also be taken into consideration. It cannot be used for detailed biological descriptions such as the characterization of populations, since differentiation between juveniles and adults is not possible. Also, if the feather pattern of the face of individuals in the field is not clearly seen after photographed, the technique could not be reliably applied (Williams & Thomson, 2015). Another further potential limitation is that not all individuals have equal probability for face feather patterns obtention. Unequal capture probability is a potential problem in all photo-identification techniques (Williams & Thomson, 2015).

Photo-identification is a potentially useful tool for understanding the demographic patterns, as well as movements of individuals of the species to other populations, with this information one could identify the natural corridors, conserve the habitat and the species itself (Langtimm et al., 2004; Patiño-Valencia et al., 2008; Pompa-Mansilla, 2007; Reyes et al., 2002; Reynolds et al., 2005). The Military Macaw is an umbrella species, meaning that the protection of this species could indirectly result in the protection of other species (Íñigo-Elías, 1999, 2000; Jiménez-Arcos et al., 2012). It is important to build a catalog of photographs of wild populations of Military Macaws for both sides of the face, because these are good predictors of individuality that can facilitate the continued evaluation of individuals over time in complex studies.

Acknowledgements

Francisco A. Rivera-Ortíz is grateful for the support provided by the Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico (DGAPA), UNAM. We thank the African Safari Zoo for allowing us to take photographs. Ariel Padilla-Ramírez provided technical assistance in the management of the SISREC software. We also thank the journal reviewers for their suggestions and comments on the manuscript, especially the Associate Editor Luis Antonio Sánchez González. Financial support was provided by Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (Conacyt) project DT006 (María del Coro Arizmendi). There were no conflicts of interest. Berenice Núñez-López and Carlos A. Soberanes-González planned and carried out fieldwork; Francisco A. Rivera-Ortíz, Berenice Núñez-López and María del Coro Arizmendi led the analyses; Francisco A. Rivera-Ortíz wrote the first draft of the manuscript; all authors contributed to analysis interpretation and to the writing of the final version of the manuscript.

Appendix 1. Identifying information for the macaws photographed in the African Safari Zoo. Contact the corresponding author if all photographs are required.

Appendix 2. Unprocessed photographs and processed images of the right and left side of the face of each Military Macaw.

References

Acevedo, A., Aguayo, A., & Pastene, N. (2006). Filopatría de la ballena jorobada (Megaptera novaeangliae Borowski, 1781), al área de alimentación del estrecho de Magallanes. Revista de Biología Mararina y Oceanografía, 41, 11–19. http://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-19572006000100004

Arizmendi, M. C., & Márquez-Valdelamar, L. (2000). Áreas de importancia para la conservación de las aves en México. México D.F: CIPAMEX.

Arroyo, B., & Bretagnolle, V. (1999). Field identification of individual Little bustard Tetrax tetrax males using plumage patterns. Ardeola, 46, 53–60.

Beck, C. A., & Osborn, R. J. (1995). Manatee individual photo-identification system. Sirenia Project, US Geological Survey. Recovered March, 2019 from: https://dspace.mote.org/bitstream/handle/2075/3453/barton-mtr.pdf?sequence=1

Beck, C. A., & Reid, J. P. (1995). An automated photo-identification catalog for studies of the life history of the Florida manatee. In T. J. O’Shea, B. B. Ackerman, & H. F. Percival (Eds.), Population biology of the Florida manatee US (pp. 135–160). Washington DC: National Biological Service.

Best, P. B., Payne, R., Rowntree, V., Truda P. J., & Do Carmo B. M. (1993). Amplio rango de movimientos de las ballenas francas del Atlántico Sur Eubalaena australis. Marine Mammal Science, 9, 227–234. http://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-19572008000300024

BirdLife International. (2020). Ara militaris, Red List of Threatened Species. UICN 2019, Recovered March, 2019 from: www.birdlife.org

Bradshaw, C. J. A., Mollet, H. F., & Meekan, M. G. (2007). Inferring population trends for the world’s largest fish from mark–recapture estimates of survival. Journal of Animal Ecology, 76, 480–489. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2006.01201.x

Bretagnolle, V., Thibault, J. C., & Dominici, J. M. (1994). Field identification of individual ospreys using head marking pattern. Journal of Wildlife Management, 58, 175–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/3809565

Buonantony, D. (2008). An analysis of utilizing the Leatherback´s Pineal Spot for photo-identification (Master Thesis in Environmental Management). Nicholas School of the Environment and Earth Sciences, Duke University. North Carolina, USA.

Calambokidis, J., Barlow, J., Ford, J. K. B., Chandler, T. E., & Douglas, A. B. (2009). Insights into the population structure of blue whales in the Eastern North Pacific from recent sightings and photographic identification. Marine Mammal Science, 25, 816–832. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2009.00298.x

Cañadas, A. M., & Sagarminaga, R. (1995). Estudio de distribución y dinámica de las poblaciones de cetáceos en las aguas del sudeste Español. Boletín del Instiuto de Estudios Almerienses, 13, 7–24.

Caro, T. M. (1994). Cheetahs of the Serengeti Plains: group living in an asocial species. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Carreón, A. G. (1997). Estimación poblacional, biología reproductiva y ecología de la nidificación de la Guacamaya verde (Ara militaris) en una selva estacional del oeste del estado de Jalisco (Tesis). Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. México, D.F.

Caughley, G. (1994). Directions in conservation biology. Journal of Animal Ecology, 63, 215– 244. https://doi.org/10.2307/5542

CITES. (1998). Appendices I, II and III to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Fora. Washington D.C.: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Department of the Interior.

Collar, N. J. (1997). Family Psittacidae (parrots). In J. Del Hoyo, A. Elliott, & J. Sargatal (Eds.), Handbook of the birds of the world (pp. 280–477). Barcelona: Lynx Eds.

Connolly, R. M., Melville, A. J., & Keesing, J. K. (2002). Abundance, movement and individual identification of leafy seadragons, Phycodurus eques (Pisces: Syngnathidae). Marine and Freshwater Research, 53, 777–780. http://doi.org/10.1071/MF01168

Constantine, R., Russell, K., Gibbs, N., Childerhouse, S., & Baker, C. S. (2007). Photo-identification of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in New Zeland waters and their migratory connections to breeding grounds of Oceania. Marine Mammal Science, 23, 715–720. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2007.00124.x

Contreras-González, A. N., Rivera-Ortíz, F. A., Soberanes-González, C., Valiente-Banuet, A., & Arizmendi, C. (2009). Feeding Ecology of Military Macaws (Ara militaris) in a semi-arid region of central México. The Wilson Journal of Ornitology, 121, 384–391. https://doi.org/10.1676/08-034.1

De Oliveira, M. C., & Rosso, S. (2008). Social organization of marine tucuxi dolphins, Sotalia guianensis, in the Cananéia Estuary of Southeastern Brazil. Journal of Mammalogy, 89, 347–355. https://doi.org/10.1644/07-MAMM-A-090R2.1

Dixon, D. R. (2003). A non-invasive technique for identifying individual badgers Meles meles. Mammal Review, 33, 92–94. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2907.2003.00001.x

Dugger, K. M., Ballard, G., Ainley, D. G., & Barton, K. J. (2006). Effects of Flipper Bands on Foraging Behavior and Survival of Adélie Penguins (Pygoscelis adeliae). The Auk, 123, 858–869. https://doi.org/10.1093/auk/123.3.858

Durán, M. A. M. R. (2003). Efecto del complejo B y vitaminas, sobre el crecimiento de las plumas remeras, en loros cariamarillos (Amazona autumnalis) en cautiverio en el centro de rescate de vida silvestre ARCAS, Petén (Tesis). Facultad de Ciencias Químicas y Farmacia, Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, Guatemala.

Foote, A. D., Similä, T., Víkingsson, G. A., & Stevick, P. T. (2009). Movement, site fidelity and connectivity in a top marine predator, the killer whale. Evolutionary Ecology, 24, 803–814. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10682-009-9337-x

Forcada, K. J., & Aguilar, A. (2000). Use of photographic identification in capture-recapture studies of Mediterranean monk seals. Marine Mammal Science, 16, 767–793. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2000.tb00971.x

Forshaw, J. M. (1989). Parrots of the world. Melbourne: Lansdowne.

Foster, J. B. (1966). The giraffe of Nairobi National Park: home range, sex ratios, the herd, and food. East African Wildlife Journal, 4, 139–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-

2028.1966.tb00889.x

Foster, G., Krijger, H., & Bangay, S. (2006). Zebra fingerprints: towards a computer-aided identification system for individual zebra. African Journal of Ecology, 45, 225–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2028.2006.00716.x

Gamble, L., Ravela, S., & McGarigal, K. (2008). Multi-scale features for identifying individuals in large biological databases: an application of pattern recognition technology to the marbled salamander Ambystoma opacum. Journal of Applied Ecology, 45, 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2007.01368.x

Gaucín, R. N., Íñigo, E. E., Treviño, C. J. Zúñiga, T. B., Sifuentes, H. G., Carmona, G. L. et al. (1999). Biología de conservación de la Guacamaya Verde (Ara militaris) en el Sótano del Barro, Querétaro. Informe final Facultad de Ciencias Naturales. Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro. Querétaro, México.

Glockner, D. A., & Venus, S. C. (1983). Identification, growth rate, and behavior of humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) cows and calves in the waters off Maui, Hawaii. In R. Payne (Eds.), Communication and behavior of whales (pp. 321–340). Denver: Westview.

Goodall, J. (1986). The chimpanzees of Gombe: patterns of behavior. Cambridge, USA: Harvard University.

Guerrero-Moreno R. E., & Álvarez-Borrego, J. (2009). Nonlinear composite filter performance. Optical Engineering, 48, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11265-020-01543-0

Íñigo-Elías, E. (1999). Las guacamayas verde y escarlata en México. Biodiversitas, 25, 7–11.

Íñigo-Elías, E. E. (2000). Guacamaya verde (Ara militaris). In G. Ceballos, & V. L. Márquez (Eds.), Las aves de México en peligro de extinción (pp. 213–215). México D.F.: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Jiménez-Arcos, V. H., Santa Cruz-Padilla, S. A., Escalona-López, A., Arizmendi, M. C., & Vázquez, L. (2012). Ampliación de la distribución y presencia de una colonia reproductiva de la guacamaya verde (Ara militaris) en el alto Balsas de Guerrero, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 83, 864–867. https://doi.org/10.7550/rmb.27460

Juniper, T., & Parr, M. (1998). Parrots. A guide to parrots of the world. London: Yale University Press.

Kelly, M. J. (2001). Computer-aided photograph matching in studies using individual identification: an example from Serengeti Cheetahs. Journal of Mammalogy, 82, 440–449. https://doi.org/10.1644/1545-1542(2001)082<0440:CAPMIS>2.0.CO;2

Langtimm, C. A., Beck, C. A., Edwards, H. H., Fick, K. J., Ackerman, B. B., Barton, S. L. et al. (2004). Survival estimates for Florida manatees from the photo-identification of individuals. Marine Mammal Science, 20, 438–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2004.tb01171.x

Limpus, C. J., Miller, J. D., Paramenter, C. J., Reimer, D., McLachlan, N., & Webb, R. (1992). Migration of green (Chelonia mydas) and loggerhead (caretta caretta) turtles to and from eastern Australian rookeries. Wildlife Research, 19, 347–357. https://doi.org/10.1071/WR9920347

Loza, S. C. (1997). Patrones de abundancia, uso de hábitat y alimentación de la Guacamaya verde (Ara militaris) en la Presa Cajón de Peña, Jalisco, México (Tesis). Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. México D.F.

Lusseau, D., Wilson, B., Hammond, P. S., Grellier, K., Durban, J. W., Parsons, K. M. et al. (2006). Quantifying the influence of sociality on population structure in bottlenose dolphins. Journal of Animal Ecology, 75, 14–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2005.01013.x

Mackey, B., Durban, J. Middlemas, S., & Thompson, P. (2007). A Bayesian estimate of harbour seal survival using sparse photo-identification data. Journal of Zoology, 274, 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.2007.00352.x

Martínez-Aguilar, S. (2008). Un modelo de abundancia absoluta de la ballena jorobada Megaptera novaeangliae, en aguas adyacentes a las islas del Archipiélago de Revillagigedo, México (Tesis). Facultad de Ciencias. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. México D.F.

Masclans, M. (2010). La fotoidentificación de carnívoros, un método de estudio científico. España, Barcelona. Recuperado en marzo, 2014 de: www.fotonatura.org/revista/articulos

Mizroch, S. A., Herman, L. M., Straley, J. M., Glockner-Ferrari, D. A., Jurasz, C., Darling, J. et al. (2004). Estimating the adult survival rate of Central North Pacific humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae). Journal of Mammalogy, 85, 963–972. https://doi.org/10.1644/BOS-123

Munn, C. (2012). Macaw biology and ecotourism, or “When a bird in the bush is worth two in the hand”. In S. Beissinger, & N. F. R. Snyder (Eds.), New World parrots in crisis: solutions from Conservation Biology (pp. 47–63). Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

McMahon, C. R., Bradshaw, A., & Hays, G. C. (2007). Applying the heat to research techniques for species conservation. Conseravtion Biology, 21, 271–273.

Nichols, W. J. & Seminoff, J. A. (1998). Plastic “Rototags” may be linked to sea turtle bycatch. Marine Turtle Newsletter, 79, 20–21.

Núñez-López, B. (2014). Diferenciación de individuos en cautiverio de la guacamaya verde (Ara militaris) por medio de la foto-identificación (Tesis). Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México D.F.

Padilla-Ramírez, A. (2012). Desarrollo de una aplicación de correlación digital. Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, México: Editorial Académica Española.

Patiño-Valencia, J. L., Vargas-Molina, A. G., & Díaz-Avalos, C. (2008). Estimación poblacional de toninas Tursiops truncatus, en la bahía de Agiabampo Sonora-Sinaloa, México en verano y otoño de 1995 al 2001. Acta Zoológica Mexicana, 19, 15–21.

Peterson, J. C. B. (1972). An identification system for zebra (Equus burchelli Gray). East African Wildlife Journal, 10, 59–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2028.1972.tb00858.x

Peterson, R. T., & Chaliff, L. E. (1989). Guía de aves de México. México D.F.: Diana.

Pompa-Mansilla, S. (2007). Distribución y abundancia de los géneros Kogia y Steno en la Bahía Banderas y aguas adyacentes (Tesis de Maestría en Ciencias Biológicas). Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. México D.F.

Renton, K. (2004). Agonistic interactions of nesting and nonbreeding macaws. The Condor, 106, 354–362. https://doi.org/10.1093/condor/106.2.354

Reyes, J., Echegaray, M., & De Paz, N. (2002). Distribución, comportamiento y conservación de cetáceos en el área Pisco-Paracas. Memorias de la Jornada Científica Reserva Nacional Paracas, 1, 136–144.

Reynolds, III, J. E., Kessenich, T. J., & Scolardi, K. M. (2005). Photo-identification and aerial surveys of manatees in Sarasota County Waters. Mote Marine Laboratory, Florida. Recovered March, 2019 from: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/a817/b3e88ee7dc70994b5e2c77ea95cf83f2d240.pdf

Ridgway, R. (1915). Ara militaris mexicanus. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington, 28,106.

Rivera-Ortíz, F. A., Contreras-González, A. M., Soberanes-González, C. A., Valiente-Banuet, A., & Arizmendi-Arriaga, M. C. (2008). Seasonal abundance and breeding chronology of the military macaw (Ara militaris) in a semi-arid region of central Mexico. Ornitología Neotropical, 19, 255–263. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmb.2016.02.002

Rivera-Ortíz, F. A., Oyama, K., Ríos-Muñoz, C. A., Solórzano, S., Navarro-Sigüenza, A. G., & Arizmendi, M. C. (2013). Habitat characterization and modeling the potential distribution of the Military Macaw (Ara militaris) in Mexico. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 84, 1210–1216. https://doi.org/10.7550/rmb.34953

Rivera-Ortíz, F. A., Solórzano, S., Arizmendi, M. C., Dávila-Aranda, P., & Oyama, K. (2016). Genetic diversity and structure of the Military Macaw (Ara militaris) in Mexico: Implications for conservation. Tropical Conservation Science, 10, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940082916684346

Rubio, Y., Beltrán, A. F., Aviléz, B. S., & Ibarra, M. (2007). Conservación de la Guacamaya Verde (Ara militaris) y otros Psitácidos en una reserva ecológica universitaria, Cosalá, Sinaloa, México. Mesoamericana, 11, 62–69.

Sélem, C., Sosa, J., & Hernández, S. (2004). Aves y mamíferos. In F. B. Zúñiga, H. D. González, J. L. Prieto, & M. C. Carranza (Eds), Técnicas de muestreo por manejadores de recursos naturales (pp. 294–300). México D.F.: Centro de Investigaciones en Geografía Ambiental, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Este es el correcto.

Semarnat. (2010). Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-059- SEMARNAT-2010, Protección ambiental – Especies nativas de México de flora y fauna silvestres – Categorías de riesgo y especificaciones para su inclusión, exclusión o cambio – Lista de especies en riesgo. Diario Oficial de la Federación. 30 de diciembre de 2010, Segunda Sección, México. http:// www.conabio.gob.mx/informacion/catalogo_autoridades/NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2001 / NOM-059-SEMARNAT2001.pdf

Sibly, R. M., Barker, D., Denham, M. C., Hone, J., & Pagel, M. (2005). On the regulation of populations of mammals, birds, fish, and insects. Science, 309, 607–610. http://doi.org/10.1126/science.1110760

Schofield, G., Katselidis, K. A., Dimopoulus, P., & Pantis, J. D. (2008). Investigating the viability of photo-identification as an objective tool to study endangered sea turtle populations. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 360, 103–108. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2008.04.005

Statsoft Inc. (1984). Statistica 6.0. Oklahoma: Statsoft Inc.

Thompson, P. M., Wilson, B., Grellier, K., & Hammond, P. S. (2000). Combining power analysis and population viability analysis to compare traditional and precautionary approaches to conservation of coastal cetaceans. Conservation Biology, 14, 1253–1263. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.00099-410.x

Trujillo-González, F. (1994). The use of photoidentification to study the Amazon River Dolphin, Inia geoffrensis, in the Colombian Amazon. Marine Mammal Science, 10, 348–353. http://doi.org/10.1111 / j.1748-7692.1994.tb00489.x

Valdes-Arellanes, M. P., Serrano, A., Heckel, G., Schramm, Y., & Martínez-Serrano, I. (2011). Abundancia de dos poblaciones de toninas (Tursiops truncatus) en el norte de Veracruz, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 82, 227–285. http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2011.1.367

Vigness-Raposa, K. J., Kenney, R. D., González, M. L., & August, P. V. (2010). Spatial patterns of humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) sightings and survey effort: Insight into North Atlantic population structure. Marine Mammal Science, 26, 161–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2009.00336.x

Williams, E. R., & Thomson, B. (2015). Improving population estimates of Glossy Black-Cockatoos (Calyptorhynchus lathami) using photoidentification. Emu, 115, 360–367. https://doi.org/10.1071/MU15041

Zar, J. (1999). Biostatistical analysis. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.