Track analysis of the funnel-web spiders (Araneae: Agelenidae) of Mexico

Julieta Maya-Morales a, María Luisa Jiménez a, Juan J. Morrone b, *

a Laboratorio de Aracnología y Entomología, Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste, Av. Instituto Politécnico Nacional 195, Playa Palo de Santa Rita Sur, 23096 La Paz, Baja California Sur, Mexico

b Museo de Zoología “Alfonso L. Herrera”, Departamento de Biología Evolutiva, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Apartado postal 70-399, 04510 México City, Mexico

*Corresponding author: juanmorrone2001@yahoo.com.mx (J. J. Morrone)

Abstract

We analyzed distributional data of 59 species of funnel-web spiders (Araneae: Agelenidae) of Mexico. We constructed individual tracks for the species analyzed, based on published and unpublished records, and based on their overlap we obtained 9 generalized tracks. Three generalized tracks belong to the Californian Nearctic dominion (Nearctic region) and 6 generalized tracks extend along the Mexican transition zone. Seven generalized tracks are defined by species of the same genus or closely related genera and 2 generalized tracks are supported by species of distantly related genera, which shows that both spatial relationships and phylogenetic evidence support the existence of ancestral biotas including unrelated taxa.

Keywords:

Biogeography; Mexican transition zone; Ageleninae

© 2018 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. Este es un artículo Open Access bajo la licencia CC BY-NC-ND

Análisis de trazos de las arañas tejedoras de red de embudo (Araneae: Agelenidae) de México

Resumen

Se analizaron los datos de distribución de 59 especies de arañas tejedoras de red de embudo (Araneae: Agelenidae) de México. Construimos los trazos individuales de las especies analizadas utilizando registros publicados y sin publicar y, con base en su superposición, obtuvimos 9 trazos generalizados. Tres trazos generalizados pertenecen al dominio Neártico Californiano (región Neártica) y 6 trazos generalizados se extienden a lo largo de la Zona de Transición Mexicana. Por otro lado, 7 trazos generalizados están definidos por especies del mismo género o géneros relacionados cercanamente y 2 trazos generalizados están apoyados por especies de géneros relacionados lejanamente, lo cual muestra que las relaciones espaciales y la evidencia filogenética sustentan la existencia de biotas ancestrales conteniendo taxones no relacionados.

Palabras clave:

Biogeografía; Zona de Transición Mexicana; Ageleninae

Introduction

The distribution of taxa represented by recorded localities in space, their relative position with respect to each other, and the links between them are the bases for biogeographical analyses (Craw et al., 1999). Track analysis is aimed to identify biotas, which are sets of spatiotemporally integrated taxa that characterize biogeographic areas and are the basic units of evolutionary biogeography (Morrone, 2004, 2010). By searching for repetitive distributional patterns, track analysis identifies biogeographically homologous distributions, allowing the correlation of distributional pattern of unrelated taxa and leading to the recognition of ancestral biotas (Morrone & Márquez, 2001).

Mexico belongs to both the Nearctic and Neotropical regions, which overlap in the Mexican transition zone, where the mixture of biotic elements is strongly favored (Morrone, 2015a; Morrone & Márquez, 2008). Additionally, smaller units are recognized, and characterized by different plant and animal taxa (Morrone, 2005). Although these taxa include several groups of arthropods (Mariño-Pérez et al., 2007; Morrone & Gutiérrez, 2005; Morrone & Márquez, 2001; Ochoa et al., 2003), there are still many terrestrial arthropods in Mexico with poor knowledge that have not been studied formally from a biogeographic perspective (Morrone & Márquez, 2008).

Agelenidae are the tenth most diverse spider family in the world, with 1,279 species (World Spider Catalog, 2017). They show restricted dispersal ability because they are not known to disperse aerially through ballooning, a typical dispersal method in spiders (Ayoub et al., 2005). Taxonomic studies of Agelenidae in Mexico have been scarce until recent years. In 1898, the first Mexican species were described from the states of Baja California Sur, Veracruz (Banks, 1898), and Morelos (Pickard-Cambridge, 1898). Gertsch described 10 more species (Gertsch, 1934, 1971; Gertsch & Davis, 1940; Gertsch & Ivie, 1936) and Roth (1968) revised the Tegenaria from Mexico. Additional species were described by Pickard-Cambridge (1902), Brignoli (1974), and García-Villafuerte (2009). Recent studies (Bolzern & Hänggi, 2016; Maya-Morales & Jiménez 2013, 2016, 2017a, b; Maya-Morales et al., 2017) have contributed to a total of 15 genera (Agelenopsis, Bajacalilena, Cabolena, Calilena, Callidalena, Eratigena, Hoffmannilena, Hololena, Lagunella, Melpomene, Novalena, Rothilena, Rualena, Tegenaria, and Tortolena) and 107 species recorded for the country, with 4 genera (Bajacalilena, Cabolena, Lagunella, and Rothilena) and 87 endemic species (Appendix 1). The family is widely distributed in Mexico in both arid and temperate habitats although some of the genera have a very limited distribution, especially in the Baja California peninsula. From biogeographic and historical perspectives Agelenopsis is the most studied genus of the family in the Western Hemisphere (Ayoub & Riechert, 2004; Ayoub et al., 2005). However, its greatest diversity is present in USA and Canada (Whitman-Zai et al., 2015). Given the high diversity, distribution, and restricted dispersal, the family may be useful in biogeographic studies. Our aim was to find distributional patterns of agelenid spiders in Mexico, using track analysis.

Material and methods

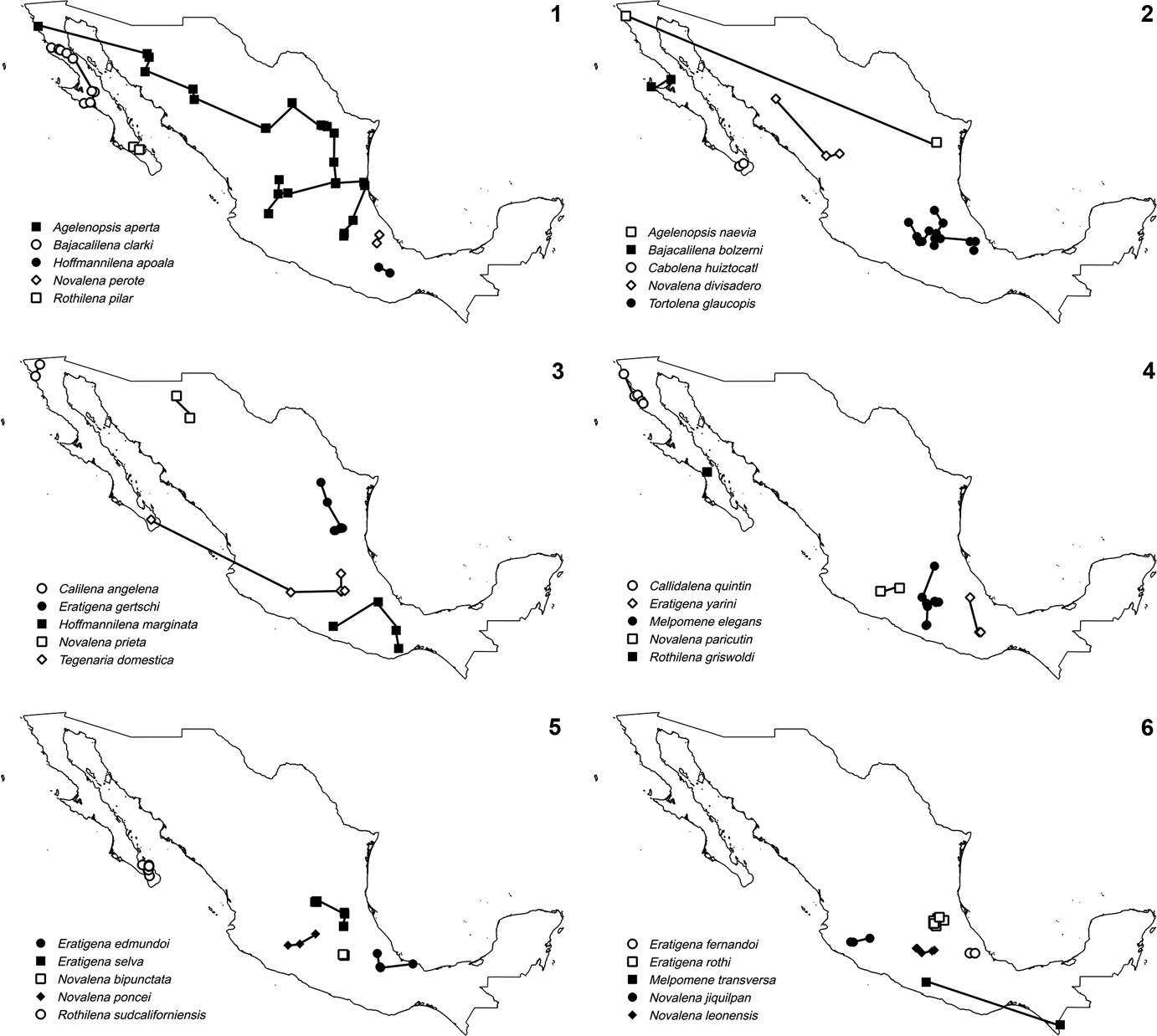

The area analyzed corresponds to Mexico. Records of agelenids were compiled from published and unpublished data. From the 107 species recorded in Mexico, we excluded those with a single record (46) or without precise localities (2). The selected species (numbers of records between brackets) are Agelenopsis aperta (26), A. naevia (2), Bajacalilena bolzerni (2), B. clarki (9), Cabolena huiztocatl (2), Calilena angelena (2), Callidalena quintin (5), Eratigena edmundoi (4), E. fernandoi (2), E. flexuosa (5), E. florea (5), E. gertschi (7), E. guanato (10), E. mexicana (10), E. queretaro (3), E. rothi (8), E. selva (12), E. tlaxcala (8), E. xilitla (10), E. yarini (3), Hoffmannilena apoala (2), H. cumbre (2), H. marginata (4), H. mitla (2), H. tizayuca (18), Hololena septata (2), Melpomene chamela (2), M. coahuilana (4), M. elegans (9), M. rita (2), M. solisi (4), M. transversa (2), Novalena annamae (5), N. approximata (48), N. atzimbo (2), N. bipunctata (2), N. chamberlini (3), N. divisadero (4), N. jiquilpan (3), N. leonensis (3), N. mexiquensis (4), N. paricutin (2), N. perote (2), N. poncei (4), N. prieta (2), N. puebla (3), N. punta (2), N. simplex (2), N. volcanes (2), Rothilena cochimi (3), R. griswoldi (2), R. pilar (2), R. sudcaliforniensis (11), Rualena cedros (4), R. magnacava (2), R. parritas (5), Tegenaria domestica (6), T. pagana (2), and Tortolena glaucopis (14).

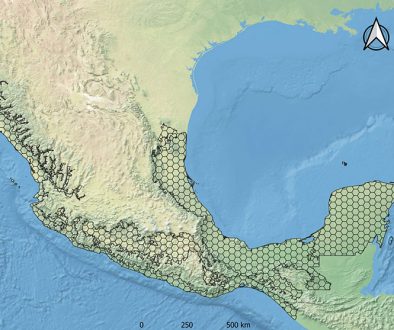

Distribution points for each species were connected with a line representing the minimum distance between them, known as individual tracks. When individual tracks match, they delimit a generalized track, which allows inferring the existence of an ancestral biota widely distributed and fragmented by vicariance events, suggesting a shared history within a biota. When 2 or more generalized tracks overlap in an area, a node is identified (Craw et al., 1999; Torres-Miranda & Luna-Vega, 2006). All maps were generated using QGIS 2.8.2 and edited with Adobe Photoshop CS6.

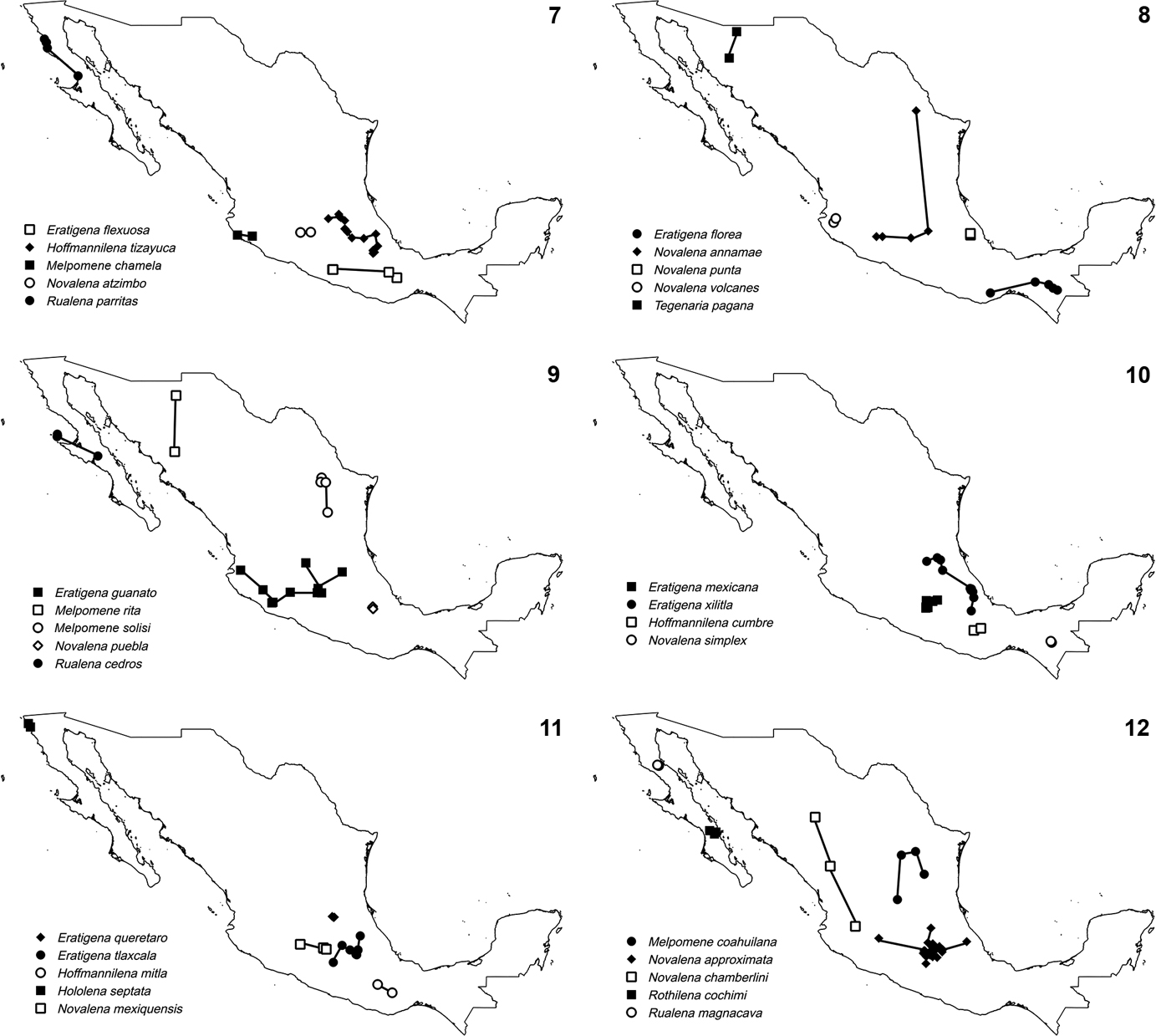

Results

Fifty-nine individual tracks were constructed. Distribution of most of the species is relatively restricted and many species are found in central Mexico (Figs 1-12). Nine generalized tracks were obtained based on 24 individual tracks (Table 1), whereas 35 individual tracks did not contribute to any of the generalized tracks found. Four generalized tracks are supported by species of the same genus: Eratigena (G), Hoffmannilena (I) and Novalena (E and H). Three generalized tracks are supported by species of closely related genera: Calilena and Hololena (A) and Bajacalilena and Rualena (B and C). Two are supported by distantly related genera: Melpomene and Novalena (D), and Eratigena and Melpomene (F) (Table 1).

Table 1

Description of generalized tracks in terms of agelenid species.

|

Generalized track |

Species |

|

A |

Calilena angelena and Hololena septata |

|

B |

Bajacalilena clarki, Rualena magnacava, and R. parritas |

|

C |

Bajacalilena bolzerni and Rualena cedros |

|

D |

Melpomene rita and Novalena prieta |

|

E |

Novalena chamberlini and N. divisadero |

|

F |

Eratigena gertchi, Melpomene coahuilana, and M. solisi |

|

G |

Eratigena queretaro, E. rothi, E. selva, and E. xilitla |

|

H |

Novalena atzimbo, N. mexiquensis, N. paricutin, and N. poncei |

|

I |

Hoffmannilena cumbre and H. mitla |

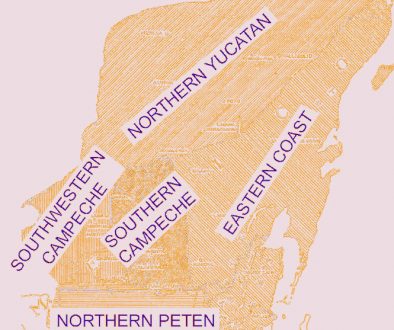

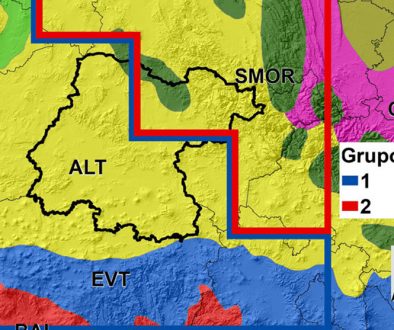

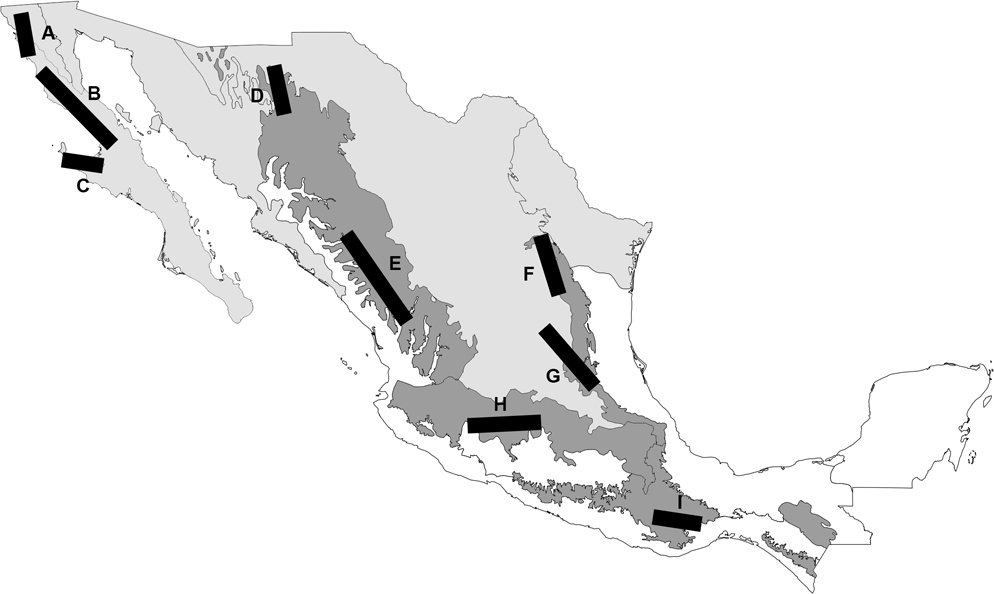

The first group of generalized tracks belongs to the Californian Nearctic dominion, of the Nearctic region (Morrone & Márquez, 2003). One generalized track runs parallel to the California and Baja California provinces (A) and 2 in the Baja California province (B and C). The second group belongs to the Mexican transition zone (Morrone, 2010, 2015a). Two generalized tracks run parallel to the Sierra Madre Occidental province (D and E), 2 across the Chihuahuan Desert and the Sierra Madre Oriental provinces (F and G), one runs parallel to the Transmexican Volcanic Belt province (H), and another runs parallel to the Sierra Madre del Sur province (I) (Fig. 13).

No nodes were found in the track analysis.

Discussion

The distributional patterns of the species analyzed show congruence with the biogeographic patterns and complexity of the country. The generalized tracks from northwestern Mexico (A, B, and C) are supported by genera that are found in arid ecosystems. The Baja California peninsula has undergone latitudinal and longitudinal displacements along the northwest to southeast peninsula starting approximately 15 million years ago (Gillespie, 2013). The region presents a highly distinctive Agelenid fauna with 10 genera and 24 species, of which 4 (40%) and 17 (70.8%) are endemic, respectively. This rate of endemism is very high compared to other families of arthropods like Formicidae (27.6% of the species; Johnson & Ward, 2002). The richness is highest in both the base of the peninsula and its southern part, which refutes the peninsula effect hypothesis (species richness declines form the base to the tip of the peninsula; Simpson, 1964). Bajacalilena is endemic to the peninsula and Callidalena is restricted to the northern part of the peninsula and southern California (Maya-Morales et al., 2017). In spiders, deep divergence has been found between Homalonychus selenopoides (Homalonychidae) on the east side of the Colorado River and its congener H. theologus on the west side including the peninsula (Crews & Hedin, 2006). Although the southern part of the peninsula presents 11 species, no generalized tracks were found. Cabolena, Lagunella, and Rothilena are restricted to this region (Maya-Morales et al., 2017), which may be related to the hypothesized vicariance event of a midpeninsular seaway during the Pleistocene (Riddle et al., 2000). Along with Bajacalilena, the generalized tracks in the peninsula are defined by species of Calilena, Hololena, and Rualena, which are Nearctic genera that have a larger distribution in western USA (Chamberlin & Ivie, 1941, 1942; Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2016). The Californian Nearctic pattern has been detected also in bird taxa (Rojas-Soto et al., 2003) and land mammals (Escalante et al., 2004).

In the Mexican transition zone, we found 4 generalized tracks defined by species of the same genus. Species of Novalena, the most diverse Agelenid genus in Mexico and the Western Hemisphere (Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b), define the generalized tracks located in the Sierra Madre Occidental province (E) and the Transmexican Volcanic Belt province (H), which presents the highest species diversity of the genus. Species of Eratigena define the generalized track across the Chihuahuan Desert and Sierra Madre Oriental provinces (G), the last one presents most of the species of the genus. Bolzern and Hänggi (2016) recognized 2 morphological groups within Nearctic and Neotropical Eratigena: the mexicana-group in central and northeastern Mexico and the flexuosa-group in southeastern Mexico. This pattern is like the spider genus Physocyclus (Pholcidae), which is distributed according to 2 phylogenetic groups, one in the Continental Nearctic and Mesoamerican dominions (north of the Transmexican Volcanic Belt province) and the second in Mexican transition zone and the Mesoamerican dominion (south of the Transmexican Volcanic Belt province) (Valdez-Mondragón, 2013). The mexicana-group of Eratigena includes 12 of the 16 endemic species from Mexico (Bolzern & Hänggi, 2016) and the species that define generalized tracks belong to the mexicana-group. Species of Hoffmannilena define the generalized track in the Sierra Madre del Sur province (I), which presents most of the species of the genus. Two generalized tracks are defined by pairs of distantly related genera (Bolzern & Hänggi, 2016): Melpomene and Novalena (D), and Eratigena and Melpomene (F). These spatial relationships shared by unrelated taxa in the form of generalized tracks may indicate that geographic constraints are not limited to the effects of local ecology on the fitness of individual populations but imply a more general process of biotic evolution (Craw et al., 1999). Generalized tracks are not only recognized when there is phylogenetic evidence supporting them but, in a more general sense, they should reflect the existence of ancestral biotas (Morrone, 2015b). Similar patterns in the Mexican transition zone have been found in Coleoptera (Liebherr, 1991; Morrone & Márquez, 2001; Toledo et al., 2007).

The absence of generalized tracks in the Continental Nearctic dominion and in the Neotropics may be the result of lack of sampling since most of the Western Hemisphere genera of Agelenidae have a Nearctic distribution and Hoffmannilena, Novalena, and Melpomene are also distributed in Central America (Chamberlin & Ivie, 1942; Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b). New systematic collects should improve the accuracy of the generalized tracks and allow finding biogeographical nodes.

We conclude that the current distribution of the Agelenid spiders of Mexico show 2 basic patterns, which correspond to the Nearctic region and the Mexican transition zone.

Appendix 1. Agelenid species recorded from Mexico. * = Mexican endemic. Provinces: BC = Baja California; BB = Balsas Basin; C = California; Ch = Chiapas; CD = Chihuahuan Desert; MG = Mexican Gulf; MPC = Mexican Pacific Coast; SMS = Sierra Madre del Sur; SMOc = Sierra Madre Occidental; SMOr = Sierra Madre Oriental; S = Sonora; T = Tamaulipas; TVB = Transmexican Volcanic Belt. aIncludes unpublished records.

|

Species |

Provinces |

Literature references |

|

Agelenopsis aperta |

BC, CD, MGa, SMOc, SMOr, S, Ta, TVB |

Ayoub & Riechert, 2004; Cruz, 2014; Gertsch & Davis, 1940; Gómez-Rodríguez & Salazar-Olivo, 2012; Lucio-Palacio, 2012; Maya-Morales, 2015; Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2013; Roth & Brown, 1986 |

|

A. naevia |

C, T |

Chamberlin, 1924; Chickering, 1937 |

|

A. potteri |

Roth & Brown, 1986 (unknown locality) |

|

|

*Bajacalilena bolzerni |

BC |

Maya-Morales et al., 2017 |

|

*B. clarki |

BC |

Maya-Morales et al., 2017 |

|

*Cabolena huiztocatl |

BC |

Maya-Morales et al., 2017 |

|

*C. kosatli |

BC |

Maya-Morales et al., 2017 |

|

*C. sotol |

BC |

Maya-Morales et al., 2017 |

|

Calilena angelena |

BC, C |

Maya-Morales et al., 2017 |

|

*C. peninsulana |

BC |

Banks, 1898 |

|

*Callidalena quintin |

BC, C |

Maya-Morales et al., 2017 |

|

C. tijuana |

C |

Maya-Morales et al., 2017 |

|

*Eratigena blanda |

SMOr |

Bolzern & Hänggi, 2016 |

|

*E. caverna |

SMOr |

Bolzern & Hänggi, 2016 |

|

*E. decora |

SMOr |

Bolzern & Hänggi, 2016 |

|

*E. edmundoi |

MG, SMS, TVB |

Bolzern & Hänggi, 2016 |

|

*E. fernandoi |

SMOr, TVB |

Bolzern & Hänggi, 2016 |

|

*E. flexuosa |

SMSa |

Bolzern & Hänggi, 2016 |

|

*E. florea |

Ch, MG, SMS |

Bolzern & Hänggi, 2016 |

|

*E. gertschi |

CD, SMOr |

Bolzern & Hänggi, 2016 |

|

*E. guanato |

BB, CD, SMS, TVBa |

Bolzern & Hänggi, 2016 |

|

*E. mexicana |

BB, TVB |

Bolzern & Hänggi, 2016 |

|

*E. queretaro |

SMOr |

Bolzern & Hänggi, 2016 |

|

*E. rothi |

MG, SMOr |

Bolzern & Hänggi, 2016 |

|

*E. selva |

CD, SMOr |

Bolzern & Hänggi, 2016 |

|

*E. tlaxcala |

SMOr, TVB |

Bolzern & Hänggi, 2016 |

|

*E. xilitla |

MG, SMS, SMOr, TVBa |

Bolzern & Hänggi, 2016 |

|

*E. yarini |

SMS, TVB |

Bolzern & Hänggi, 2016 |

|

*Hoffmannilena apoala |

SMS |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2016 |

|

*H. cumbre |

SMS |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2016 |

|

*H. huajuapan |

SMS |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2016 |

|

*H. lobata |

SMS |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2016 |

|

*H. marginata |

SMS |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2016 |

|

*H. mitla |

SMS |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2016 |

|

*H. tizayuca |

CD, SMS, TVB |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2016 |

|

*H. variabilis |

SMS |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2016 |

|

Hololena hola |

Roth & Brown, 1986 (unknown locality) |

|

|

H. septata |

C |

Maya-Morales et al., 2017 |

|

*Lagunella guaycura |

BC |

Maya-Morales et al., 2017 |

|

Melpomene bicavata |

SMS |

Pickard-Cambridge, 1902 |

|

*M. chamela |

MPC |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017a |

|

*M. coahuilana |

CD, SMOra |

Chamberlin & Ivie, 1942; Gertsch & Davis, 1940; Gómez-Rodríguez & Salazar-Olivo, 2012 |

|

*M. elegans |

BBa, SMS, SMOr, TVB |

Guerrero-Fuentes, 2014; Maya-Morales, 2015; Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017a; Pickard-Cambridge, 1898 |

|

M. rita |

CD, SMOc |

Roth & Brown, 1986 |

|

*M. singula |

SMS |

Gertsch & Ivie, 1936 |

|

*M. solisi |

SMOr, T |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017a |

|

M. transversa |

Ch, SMS |

Ibarra-Núñez et al., 2011; Pickard-Cambridge, 1902 |

|

*Novalena ajusco |

TVB |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. alamo |

SMOc |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. alvarezi |

TVB |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. annamae |

BB, T, TVB |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

N. approximata |

BB, CD, SMOr, TVB |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

N. attenuata |

SMS |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. atzimbo |

TVB |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

N. bipunctata |

TVB |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. bosencheve |

TVB |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. chamberlini |

SMOc, TVB |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. cieneguilla |

SMOr |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. cintalapa |

Ch |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. clara |

SMOc |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. comaltepec |

SMS |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. creel |

SMOc |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. dentata |

TVB |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. divisadero |

SMOc |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. durango |

SMOc |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. franckei |

TVB |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. garnica |

TVB |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. gibarrai |

Ch |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. iviei |

MPC |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. ixtlan |

SMS |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. jiquilpan |

MPC, TVB |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. leonensis |

TVB |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. mexiquensis |

TVB |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. oaxaca |

SMS |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. orizaba |

SMS |

Banks, 1898 |

|

*N. paricutin |

TVB |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. perote |

SMOr |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. poncei |

TVB |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. popoca |

TVB |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. prieta |

CD, SMOc |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. puebla |

TVB |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. punta |

SMOr, TVB |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. saltoensis |

SMOc |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. shlomitae |

Ch |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

N. simplex |

Ch |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. sinaloa |

MPC |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

N. tacana |

Ch |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. triunfo |

Ch |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. valdezi |

SMS |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. victoria |

TVB |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*N. volcanes |

TVB |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2017b |

|

*Rothilena cochimi |

BC |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2013; Maya-Morales et al., 2017 |

|

*R. golondrina |

BC |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2013 |

|

*R. griswoldi |

BC |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2013 |

|

*R. naranjensis |

BC |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2013 |

|

*R. pilar |

BC |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2013; Maya-Morales et al., 2017 |

|

*R. sudcaliforniensis |

BC |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2013; Maya-Morales et al., 2017 |

|

*Rualena cavata |

SMS |

Pickard-Cambridge, 1902 |

|

*R. cedros |

BCa |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2016 |

|

R. magnacava |

BC |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2016 |

|

*R. parritas |

BC |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2016 |

|

*R. pasquinii |

Ch |

Brignoli, 1974 |

|

*R. ubicki |

BC |

Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2016 |

|

Tegenaria domestica |

BC, CD, TVB |

Banks, 1898; Durán-Barrón et al., 2009; Roth, 1952, 1968 |

|

T. pagana |

CDa, S |

Banks, 1898 |

|

Tortolena dela |

T |

First record in Mexico (T. glaucopis in Chickering, 1937) |

|

T. glaucopis |

BB, CD, SMSa, SMOra, TVBa |

Álvarez-Padilla Laboratory, 2017; Chamberlin & Ivie, 1941; Cruz, 2014; Durán-Barrón et al., 2009; Jiménez, 1989; Maya-Morales, 2015; Maya-Morales & Jiménez, 2013; Medina, 2002; Pickard-Cambridge, 1902 |

Acknowledgments

We thank to César G. Durán Barrón, Alejandro Valdez Mondragón, and the anonymous reviewers, who provided useful suggestions that helped improve the manuscript.

References

Álvarez-Padilla Laboratory. (2017). Cyberdiversity of Araneomorphae from Mexico. Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Retrieved on June 25, 2017 from: http://unamfcaracnolab.com

Ayoub, N. A., & Riechert, S. E. (2004). Molecular evidence for Pleistocene glacial cycles driving diversification of a North American desert spider, Agelenopsis aperta. Molecular Ecology, 13, 3453–3465.

Ayoub, N. A., Riechert, S. E., & Small, R. L. (2005). Speciation history of the North American funnel web spiders, Agelenopsis (Araneae: Agelenidae): phylogenetic inferences at the population-species interface. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 36, 42–57.

Banks, N. (1898). Arachnida from Baja California and other parts of Mexico. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences, 1, 205–308.

Bolzern, A., & Hänggi, A. (2016). Revision of the Nearctic Eratigena and Tegenaria species (Araneae: Agelenidae). Journal of Arachnology, 44, 105–141.

Brignoli, P. M. (1974). Notes on spiders, mainly cave-dwelling, of southern Mexico and Guatemala (Araneae). Quaderna Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, 171, 195–238.

Chamberlin, R. V. (1924). The spider fauna of the shores and islands of the Golf of California. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences, 12, 562–694.

Chamberlin, R. V., & Ivie, W. (1941). North American Agelenidae of the genera Agelenopsis, Calilena, Ritalena, and Tortolena. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 34, 585–628.

Chamberlin, R. V., & Ivie, W. (1942). Agelenidae of the genera Hololena, Novalena, Rualena, and Melpomene. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 35, 203–241.

Chickering, A. M. (1937). Notes and studies on Arachinida. III. Arachnida from the San Carlos mountains. In H. H. Bartlett, E. S. Bastin, L. R. Dice, R. W. Imlay, L. B. Kellum, G. W. Rust et al. (Eds.), The geology and biology of the San Carlos mountains, Tamaulipas, Mexico (pp. 271–283). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Craw, R. C., Grehan, J. R., & Heads, M. J. (1999). Panbiogeography: tracking the history of life. New York: Oxford University Press.

Crews, S. C., & Hedin, M. (2006). Studies of morphological and molecular phylogenetic divergence in spiders (Araneae: Homalonychus) from the American southwest, including divergence along the Baja California Peninsula. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 38, 470–487.

Cruz, D. A. (2014). Biodiversidad de arañas (Arachnida: Araneae) del Parque Estatal Sierra de Guadalupe (Bachelor’s degree Thesis). México City: Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas, Instituto Politécnico Nacional.

Durán-Barrón, C. G., Francke, O. F., & Pérez-Ortiz, T. M. (2009). Diversidad de arañas (Arachnida: Araneae) asociadas con viviendas de la ciudad de México (Zona Metropolitana). Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 80, 55–69.

Escalante, T., Rodríguez, G., & Morrone, J. J. (2004). The diversification of Nearctic mammals in the Mexican transition zone. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 83, 327–339.

García-Villafuerte, M. A. (2009). A new species of Rualena (Araneae, Agelenidae) from Chiapas, Mexico. Revista Ibérica de Aracnología, 17, 7–11.

Gertsch, W. J. (1934). Further notes on American spiders. American Museum Novitates, 726, 1–26.

Gertsch, W. J. (1971). A report on some Mexican cave spiders. Association for Mexican Cave Studies Bulletin, 4, 47–111.

Gertsch, W. J., & Davis, L. I. (1940). Report on a collection of spiders from Mexico. II. American Museum Novitates, 1059, 1–18.

Gertsch, W. J., & Ivie, W. (1936). Descriptions of new American spiders. American Museum Novitates, 858, 1–25.

Gillespie, R. G. (2013). Biogeography. From testing patterns to understanding processes in spiders and related arachnids, Chapter 4. In D. Penney (Ed.), Spider research in the 21st Century: trends & perspectives (pp. 154–185). Manchester: Siri Scientific Press.

Gómez-Rodríguez, J. R., & Salazar-Olivo, C. A. (2012). Arañas de la región montañosa de Miquihuana, Tamaulipas: listado faunístico y registros nuevos. Dugesiana, 19, 1–7.

Guerrero-Fuentes, D. R. (2014). Diversidad de arañas del clado RTA (Arachnida: Araneae) de Tonatico, Estado de México (Bachelor Thesis). Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México. Toluca, Estado de México, Mexico.

Ibarra-Núñez, G., Maya-Morales, J., & Chamé-Vázquez, D. (2011). Las arañas del bosque mesófilo de montaña de la Reserva de la Biosfera Volcán Tacaná, Chiapas, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 82, 1183–1193.

Jiménez, M. L. (1989). Las arañas Araneomorphae de San Francisco Oxtilpan, Estado de México (Doctoral Thesis). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. México City, Mexico.

Johnson, R. A., & Ward, P. S. (2002). Biogeography and endemism of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Baja California, Mexico: a first overview. Journal of Biogeography, 29, 1009–1026.

Liebherr, J. K. (1991). A general area cladogram for montane Mexico based on distributions in the Platynine genera Elliptoleus and Calathus (Coleoptera: Carabidae). Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington, 93, 390–406.

Lucio-Palacio, C. R. (2012). Nuevos registros de arañas errantes para el estado de Aguascalientes, México. Dugesiana, 19, 35–36.

Mariño-Pérez, R., Brailovsky, H., & Morrone, J. J. (2007). Análisis panbiogeográfico de las especies mexicanas de Pselliopus Bergroth (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Reduviidae: Harpactorinae). Acta Zoológica Mexicana, 23, 77–88.

Maya-Morales, J. (2015). Sistemática de las arañas de la familia Agelenidae (Araneae: Araneomorphae) de México (Doctoral Thesis). Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas de Noroeste. La Paz, Baja California Sur, Mexico.

Maya-Morales, J., & Jiménez, M. L. (2013). Rothilena (Araneae: Agelenidae), a new genus of funnel-web spiders endemic to the Baja California Peninsula. Zootaxa, 3718, 441–466.

Maya-Morales, J., & Jiménez, M. L. (2016). Taxonomic revision of the spider genus Rualena Chamberlin & Ivie 1942 and description of Hoffmannilena, a new genus from Mexico (Araneae: Agelenidae). Zootaxa, 4084, 1–49.

Maya-Morales, J. & Jiménez, M. L. (2017a). Dos especies nuevas de Melpomene de México y descripción de la hembra de Melpomene elegans (Araneae: Agelenidae). Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 88, 579–586.

Maya-Morales, J., & Jiménez, M. L. (2017b). Revision of the funnel-web spider genus Novalena (Araneae: Agelenidae). Zootaxa, 4262, 1–88.

Maya-Morales, J., Jiménez, M. L., Murugan, G., & Palacios-Cardiel, C. (2017). Four new genera of funnel-web spiders (Araneae: Agelenidae) from the Baja California Peninsula in Mexico. Journal of Arachnology, 45, 30–66.

Medina, F. J. (2002). Las arañas y su distribución temporal en un bosque de San Martín Cachihuapan, Municipio de Villa del Carbón, Estado de México (Bachelor’s degree Thesis). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México City, Mexico.

Morrone, J. J. (2004). Panbiogeografía, componentes bióticos y zonas de transición. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia, 48, 149–162.

Morrone, J. J. (2005). Hacia una síntesis biogeográfica de México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 76, 207–252.

Morrone, J. J. (2010). Fundamental biogeographic pattern across the Mexican Transition Zone: an evolutionary approach. Ecography, 33, 355–361.

Morrone, J. J. (2015a). Halffter’s Mexican transition zone (1962–2014), cenocrons and evolutionary biogeography. Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research, 53, 249–257.

Morrone, J. J. (2015b). Track analysis beyond panbiogeography. Journal of Biogeography, 42, 413–425.

Morrone, J. J., & Gutiérrez, A. (2005). Do fleas (Insecta: Siphonaptera) parallel their mammal host diversification in the Mexican transition zone? Journal of Biogeography, 32, 1315–1325.

Morrone, J. J., & Márquez, J. (2001). Halffter’s Mexican Transition Zone, beetle generalized tracks, and geographical homology. Journal of Biogeography, 28, 635–650.

Morrone, J. J., & Márquez, J. (2003). Aproximación a un atlas biogeográfico mexicano: componentes bióticos principales y provincias biogeográficas. In J. J. Morrone, & J. Llorente-Bousquets (Eds.), Una perspectiva latinoamericana de la biogeografía (pp. 217–220). Las Prensas de Ciencias, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México City, Mexico.

Morrone, J. J., & Márquez, J. (2008). Biodiversity of Mexican terrestrial arthropods (Arachnida and Hexapoda): a biogeographical puzzle. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (nueva serie), 24, 15–41.

Ochoa, L., Cruz, B., García, G., & Luis-Martínez, A. (2003). Contribución al atlas panbiogeográfico de México: los géneros Adelpha y Hamadryas (Nymphalidae), y Dismorphia, Enantia, Lienix y Pseudopieris (Pieridae) (Papilionoidae; Lepidoptera). Folia Entomológica Mexicana, 42, 65–77.

Pickard-Cambridge, F. O. (1898). Arachnida – Araneidea, Volume I. In Biologia Centrali-Americana, Zoology. London: R. H. Porter.

Pickard-Cambridge, F. O. (1902). Arachnida – Araneidea and Opiliones, Volume II. In Biologia Centrali-Americana, Zoology. London: R. H. Porter.

Riddle, B. R., Hafner, D. J., Alexander, L. F., & Jaeger, J. F. (2000). Cryptic vicariance in the historical assembly of a Baja California Peninsular Desert biota. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 97, 14438–14443.

Rojas-Soto, O. R., Alcántara-Ayala, O., & Navarro, A. (2003). Regionalization of the avifauna of the Baja California Peninsula, Mexico: a parsimony analysis of endemicity and distributional modeling approach. Journal of Biogeography, 30, 449–461.

Roth, V. D. (1952). A review of the genus Tegenaria in North America (Arachnida: Agelenidae). Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences, 42, 238–288.

Roth, V. D. (1968). The spider genus Tegenaria in the Western Hemisphere (Agelenidae). American Museum Novitates, 2323, 1–33.

Roth, V. D., & Brown, W. L. (1986). Catalog of Nearctic Agelenidae. Occasional Papers of the Museum Texas Tech University, 99, 1–21.

Simpson, G. G. (1964). Species density of North American recent mammals. Systematic Zoology, 13, 57–73.

Toledo, V. H., Corona, A. M., & Morrone, J. J. (2007). Track analysis of the Mexican species of Cerambycidae (Insecta,

Coleoptera). Revista Brasileira de Entomologia, 51, 131–137.

Torres-Miranda, A., & Luna-Vega, I. (2006). Análisis de trazos para establecer áreas de conservación en la Faja Volcánica Transmexicana. Interciencia, 31, 849–855.

Valdez-Mondragón, A. (2013). Morphological phylogenetic analysis of the spider genus Physocyclus (Araneae: Pholcidae). Journal of Arachnology, 41, 184–196.

Whitman-Zai, J., Francis, M., Geick, M., & Cushing, P. E. (2015). Revision and morphological phylogenetic analysis of the funnel web spider genus Agelenopsis (Araneae: Agelenidae). Journal of Arachnology, 43, 1–25.

World Spider Catalog (2017). World Spider Catalog. Natural History Museum, Bern. Retrieved on October 9, 2017 from: http://wsc.nmbe.ch/