Saprophytic synnematous microfungi. New records and known species for Mexico

Gabriela Heredia a, *, Rosa María Arias-Mota a, Julio Mena-Portales b, Rafael F. Castañeda-Ruiz c

a Instituto de Ecología A.C., Carretera Antigua a Coatepec Núm. 351, Congregación El Haya, 91070 Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico

b Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática, Carretera de Varona Km 3.5 A.P. 8029, Capdevila, Boyeros, La Habana, Cuba

c Instituto de Investigaciones Fundamentales en Agricultura Tropical “Alejandro de Humboldt”, Calle 1 Esq. 2, Santiago de Las Vegas, C. Habana, Cuba

* Corresponding author: gabriela.heredia@inecol.mx (G. Heredia)

Abstract

In this contribution, 18 species of synnematous microfungi associated with plant debris are registered for the first time to the Mexican mycobiota. In addition, an account of the current state of knowledge of the synnematous species registered to date is presented. The taxonomic determination was carried out by morphological analysis of the specimens growing in natural substrate incubated in damp chambers. Arthrobotryum stilboideum, Blastocatena pulneyensis, Coremiella cubispora, Menisporopsis multisetula and Phaeoisaria clavulata are new records for the Neotropical region. Blastocatena pulneyensis, Menisporopsis anisospora and Roigiella lignicola, which have not been recorded since their original descriptions were also determined. Including the records of this study, a total of 40 species belonging to 28 genera of synnematous microfungi have been registered for Mexico. No information was found for most of the states in the country. For the 18 species recorded in the present study, descriptions, illustrations and information about their substrates and geographical distribution are provided. Reference material was deposited in the Herbarium of the Instituto de Ecología A.C. (XAL) in Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico.

Keywords:

Conidial fungi; Taxonomy; Hyphomycetes; Mycobiota

© 2018 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. Este es un artículo Open Access bajo la licencia CC BY-NC-ND

Micromicetos sinematosos saprobios. Registros nuevos y especies descritas para México

Resumen

Se registran para México 18 especies de micromicetos sinematosos asociados a restos vegetales y se expone el estado actual del conocimiento de las especies con sinemas descritas para la micobiota mexicana. La determinación taxonómica se llevó a cabo mediante el análisis morfológico de sus estructuras reproductoras desarrolladas en substratos naturales incubados en cámaras húmedas. Arthrobotryum stilboideum, Blastocatena pulneyensis, Coremiella cubispora, Menisporopsis multisetula y Phaeoisaria clavulata son registros nuevos para la región Neotropical. Así mismo, Blastocatena pulneyensis, Menisporopsis anisospora y Roigiella lignicola no habían sido recolectadas desde que fueron descritas como especies nuevas. Con la presente colaboración y la información recabada, un total de 40 especies y 28 géneros de micromicetos conidiales sinematosos han sido registrados para México. Para la mayoría de los estados no se cuenta con información de estos hongos. Para todos los registros, junto con la descripción morfológica, se incluye información sobre los substratos en que proliferan, su distribución geográfica e ilustraciones. El material de referencia está depositado en el Herbario del Instituto de Ecología A.C. (XAL), en Xalapa, Veracruz, México.

© 2018 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license

Palabras clave:

Hongos conidiales; Taxonomía; Hyphomycetes; Micobiota

Introduction

Los ambientes subaéreos son aquellos que cuentan con una cantidad de agua intermitente, ya sea por la lluvia, goteo, niebla o por un flujo de agua corriente (Komárek y Anagnostidis, 1998). Dependiendo del sustrato (rocas, suelos, cortezas de árboles, plantas) en estos hábitats se desarrollan principalmente cianoprocariontes, clorofitas, diatomeas, rodofitas, que forman crecimientos de muchos tipos (biopelículas, tapetes, fieltros, etcétera).

Los objetos del patrimonio cultural también son colonizados por microorganismos, lo que impacta sobre su aspecto estético y su estado de conservación para las futuras generaciones (Allsopp et al., 2004). Como consecuencia, existe un interés por conocer las especies que integran los crecimientos de microorganismos que habitan sobre los bienes culturales, así como sus ciclos de vida y su fisiología, de modo que se puedan planificar estrategias que ayuden a conservar los objetos de valor artístico o histórico.

En México, el interés por la conservación del patrimonio cultural material y por el conocimiento de la ficoflora, originó que se realizaran estudios en las zonas arqueológicas de la cultura maya de Palenque, Yaxchilán y Bonampak, Chiapas (Herbert-Pesquera, 2008; Loyo, 2009, 2015; Mireles, 2012; Pedraza, 2014; Ramírez, 2006, 2012; Ramírez et al., 2009, 2010, 2011; Torres, 1993), registrando 159 especies para estos sitios, de las cuales el 63.2% corresponde a Chroococcales, 29.2% a Nostocales, 5.6% a Oscillatoriales, 0.9% a Trentepohliales y 0.9% a Fragilariales.

El objetivo de este trabajo fue documentar la riqueza de especies de algas y cianoprocariontes que conforman los crecimientos epilíticos que se desarrollan sobre los monumentos de la Zona Arqueológica (ZA) de Yaxchilán, Chiapas, México.

Conidial microfungi contain a large diversity of species that are widely distributed across most ecological niches. The majority of conidial microfungi correspond with the asexual states of ascomycetes or, rarely, of basidiomycetes (Kendrick, 2001). Reproduction in these fungi occurs mainly through the production of mitotic spores called conidia, which are borne from conidiogenous cells supported on differentiated cells named conidiophores. Conidiophores are usually solitary although sometimes form aggregations called conidiomata. Acervuli, pycnidia, sporodochia, and synnemata are characteristic conidiomata. In the synnematous microfungi, the conidia are supported by a more or less compacted group of long, erect and sometimes fused conidiophores, which can form conspicuous stipes or fascicules. In the taxonomic system developed by Saccardo, synnematous species were placed in the family Stilbellaceae (or Stilbaceae). This classification system was followed for a long time, yet has currently been abandoned, since it is well documented that it does not represent phylogenetically natural groups (Seifert et al., 2011). However, for identification purposes, grouping the synnematous species is still a common practice that has been the subject of many studies and treaties as those of Gusmão and Grandi (1997), Jong and Morris (1968), Morris (1963; 1966; 1967), Rong and Botha (1993) and Seifert (1990).

Records of synnematous microfungi from Mexico are scattered in the literature. Considering the variety of natural environments in Mexico, a significant diversity of synnematous species likely remains to be discovered. So, in the present paper, the objectives are to describe and record 18 species of saprobic synnematous microfungi previously unknown in Mexico, and to present an account of the synnematous microfungi registered for the Mexican mycobiota up to date. For the latter objective, only species published in refereed journals and documented with herbarium material deposited in registered collections are considered.

Materials and methods

Samples of plant debris consisting of leaf litter, dead branches, palm rachides and petioles, were collected in different tropical and semitropical localities of the state of Veracruz. In the laboratory, plant material was treated following Castañeda-Ruiz et al. (2016). Plant debris was regularly examined under a stereomicroscope to detect fungal sporulation. Permanent slides were prepared with polyvinyl alcohol-glycerol as a mounting medium. The material was examined and photographed using a Nikon 80i phase microscope. Photomicrographs and measurements were captured using a Nikon DS-L3 camera adapted to a Nikon 80i microscope. Fungal species were determined through their conidial ontogeny, conidiogenous events and morphological features. All specimens consisting of permanent slides were deposited in the fungal collection of the Instituto de Ecología A. C. Herbarium (XAL). For the geographical distribution research, the following databases were consulted:

Cybernome (http://www.cybertruffle.org.uk/cybernome/eng), Cybertruffle’s Robigalia (http://www.cybertruffle.org.uk/robigalia/eng/), Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF: http://www.gbif.org/), Landcare Research Manaaki Whenua, Virtual Fungal Dried Reference Collection of New York Botanic Garden and USDA Fungal Databases.

Descriptions

Arthrobotryum stilboideum Ces., 1854. Hedwigia 1: tab. 4, fig. 1.

Plate 1. Fig. 1, 1a

Synnemata scattered or in small groups, cylindrical, dark brown, up to 1,000 μm long × 40-65 μm wide, with a globose or subglobose pale orange head composed of spores embedded in mucilage. Conidiophores threads adhering closely to each other along their length, dark brown, paler above. Conidiogenous cells holoblastic, integrated and terminal, pale brown. Conidia ellipsoidal or cylindrical, rounded at the apex, pale brown, smooth, 1-3 transverse septa, 11-13 × 2.5-3.5 μm.

Taxonomic summary

Veracruz, Texolo, Mpio. Xicochimalco, E. Hernández, 2/12/1995, CB659-2, on dead branches.

Geographical distribution and substrate known: Arthrobotryum stilboideum is a lignicolous fungus, registered in several countries of Europe (Ellis, 1971), India (Chavan & Bhambure, 1975; Kapoor & Munjal, 1966), Taiwan (Chang, 1989), South Africa (GBIF: http://www.gbif.org/) and Iran (Gharizadeh et al., 2007). The present collection is the first record for this species in the Neotropical region.

Bactrodesmium longisporum M.B. Ellis, 1976. More dematiaceous Hyphomycetes: 68. Plate 1. Fig. 2

≡ Stigmina longispora var. stilboidea (R.F. Castañeda & G.R.W. Arnold) J. Mena & Mercado, 1987. Rep. de Investigación del Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática, Academia de Ciencias de Cuba, Ser. Bot. 17: 10.

≡ Bactrodesmium stilboideum R.F. Castañeda & G.R.W. Arnold, 1985. Revta. Jardín Bot. Nac., Univ. Habana 6(1): 48.

≡ Stigmina longispora (M.B. Ellis) S. Hughes, 1978. N.Z. Jl Bot. 16(3): 353.

Synnemata or sporodochia scattered, superficial, up to 167 μm long, brown to pale brown Conidiophores fasciculate, straight or flexuous, smooth, pale brown up to 90 μm long. Conidiogenous cells holoblastic, integrated and terminal, pale brown. Conidia subulate, truncate at the base, up to 17 transverse septa, pale brown, smooth, 50-80 × 7-8 μm, with the apex often enveloped by a thin spherical sheath.

Taxonomic summary

Veracruz, Las Cañadas, Mpio. Huatusco, M. Reyes, G. Heredia, 21/7/1999, CB806, on dead branches. Veracruz, Agüita Fría, Mpio. San Andrés Tlalnehuayocan, G. Heredia, 07/02/10, CB1705; CB1706; CB1707, on dead wood. Veracruz, San Martín Tuxtla, Mpio. San Andrés Tuxtla, G. Heredia, 05/01/11, CB2016, on dead wood.

Comments: except for the CB806 specimen, which has a typical synnemata, the rest of the material studied have sporodochia. The presence of both conidiomata is common in this species.

Distribution and substrate known: Bactrodesmium longisporum has been widely collected mainly in tropical areas, including Cuba (Castañeda-Ruiz & Günter, 1985; Cybernome: http://www.cybertruffle.org.uk/cybernome/eng), India (Rao & de Hoog, 1986), Peru (Matsushima, 1993), Hong Kong (Wong & Hyde, 2001), Filipinas (Cai et al., 2003), Australia, (Vijaykrishna & Hyde, 2006), Venezuela (Castañeda-Ruiz et al., 2009), Brazil (Barbosa & Gusmão, 2011; Santa Izabel & Gusmão, 2016) and Guatemala (Figueroa et al., 2016). There is also information from Bulgaria (Huseyin et al., 2011), Taiwan (GBIF, http://www.gbif.org/), South Africa and Great Britain (Ellis, 1976). This species has been collected mainly on decaying lignified substrates.

Blastocatena pulneyensis Subram. & Bhat, 1987. Kavaka 15(1-2): 44.

Plate 1. Fig. 3, 3a

Synnemata scattered, singly or in groups, fertile from the lower middle to the apical region, up to 710 long × 45-70 μm wide at the base. Conidiophores septate, simple, straight or flexuous smooth, hyaline to subhyaline. Conidiogenous cells holoblastic, hood-like, hyaline. Conidia, developing in acropetal chains, obovoid to cylindrical, sometimes curved in the middle, thick-walled, smooth, 3-5-distoseptate, subhyaline, 21-36 × 6-7 μm.

Taxonomic summary

Veracruz, Comapa, Mpio. Comapa, J. Mena-Portales, 16/06/1995, CB434, on a dead branches of palm leaf.

Geographical distribution and substrate known: this species had not been registered since Subramanian and Bhat described the type specimen, collected in South India on dead twigs (Subramaniam & Bhat, 1987). Thereby this is the first record for the Neotropical region.

Cephalotrichum microsporum (Sacc.) P.M. Kirk, 1984. Kew Bull. 38(4): 578.

Plate 1. Fig. 4, 4a

≡ Doratomyces microsporus (Sacc.) F.J. Morton & G. Sm., 1963. Mycol. Pap. 86: 77.

≡ Graphium graminum Cooke, 1887. Grevillea 16, p. 11.

≡ Stysanus microsporus Sacc., 1878. Michelia 1: 274.

Synnemata thin, straight or flexuous, with long cylindrical fertile heads, brown to dark brown, up to 982 μm long × 23-30 μm wide at the base. Conidiophores septate, straight or flexuous, smooth, dark brown, branched towards the apex. Conidiogenous cells monoblastic, integrated, ampulliform, pale brown. Conidia obovoid with truncate base and rounded or acutely pointed apex, smooth, subhyaline and pale brown, 0-septate, 3-5 × 2-3μm.

Taxonomic summary

Veracruz, Botanical garden F. J. Clavijero, Mpio. Xalapa, G. Heredia, 30/11/2001, CB811, on dead branches.

Geographical distribution and substrate known: Cephalotrichum microsporum has a worldwide distribution, it has been found on a wide variety of substrates as seeds, dung, soil, rot wood, dead leaves and compost (Domsch et al., 1980; Ellis, 1971).

Cephalotrichum purpureofuscum (S. Hughes) S. Hughes, 1958. Can. J. Bot. 36: 744.

Plate 1. Fig. 5, 5a

≡ Doratomyces purpureofuscus (Fr.) F.J. Morton & G. Sm., 1963. Mycol. Pap. 86: 74.

≡ Stysanus purpureofuscus (Fr.) Hughes, 1953. Can. J. Bot. 31: 615.

≡ Aspergillus purpureofuscus Schwein, 1832. Trans. Am.

Phil. Soc., New Series 4(2): 282.

Synnemata thin, straight or flexuous, with spherical or subspherical fertile heads, dark grey to blackish brown, up to 350 μm long × 8-16 μm wide at the base. Conidiophores septate, straight or flexuous, smooth, dark grey, branched towards the apex. Conidiogenous cells monoblastic, integrated, ampulliform, dark to pale grey. Conidia ovoid to oblong, round at the apex, smooth, pale grey, 0-septate, 5-7 × 3.5-5 μm.

Taxonomic summary

Veracruz, Botanical garden F. J. Clavijero, Mpio. Xalapa, R.M. Arias, 30/11/2001, CB808, CB809, on dead branches.

Geographical distribution and substrate known: Cephalotrichum purpureofuscum is a cosmopolitan species, common on plant debris, also isolated from dung and soil (Domsch et al., 1980; Ellis, 1971; Morton & Smith, 1963).

Coremiella cubispora (Berk. & M.A. Curtis) M.B. Ellis, 1971. Dematiaceous Hyphomycetes: 33.

Plate 2. Fig. 7, 7a

≡ Cladosporium cubisporum Berk. & M.A. Curtis, 1875, apud Berk. In Grevillea 3: 107.

≡ Coremiella ulmariae (McWeeney) E.W. Mason, Hughes, 1953. Can. J. Bot. 31: 640.

Synnemata scattered, forming a loose coremia, arising singly or in groups, fertile in the upper half, pale gray to mid olivaceous brown, 500-790 μm long, and up to 340 μm wide at the base. Conidiophores septate, simple, straight or flexuous smooth, hyaline to pale gray. Conidiogenous cells fragmenting, hyaline. Conidia, catenate, oblong or cubical, 0-septate, smooth, hyaline, subhyaline, pale mid olivaceous brown together, 4.5-8 × 4-8 μm.

Taxonomic summary

Veracruz, Botanical garden, F. J. Clavijero, Mpio. Xalapa, S. Gómez, 02/ 03/2006, CB902, on rotten wood.

Geographical distribution and substrate known: Coremiella cubispora has been collected in Great Britain, USA (Ellis, 1971), Russia (Tikhomirova, 1989), Kenya (Sutton, 1993), India (Prasher & Singh, 2013) and Malawi (Cybernome, 2017), on submerged and terrestrial vegetable remains. The present collection is the first record for this species in the Neotropical region.

Didymostilbe capsici (Pat.) Seifert, 1985. Stud. Mycol. 27: 135.

Plate 1. Fig. 6, 6a

≡ Stilbum capsici Pat. 1893. Bull. Soc. Mycol. Fr. 9: 163.

Synnemata scattered, gregarious, or caespitose, cylindrical-capitate, fertile in the upper, white, up to 1,619 μm long × 88-195 μm wide at the base. Conidiophores threads adhering closely to each other along their length, subhyaline. Conidiogenous cells phialidic, cylindrical to clavate, hyaline. Conidia, ellipsoidal to oblong-ellipsoidal, with a truncate or nipple-like base, 0-septate, 15-23 × 5-10 μm, with granular cytoplasm.

Taxonomic summary

Veracruz, Ranch Guadalupe, Mpio. Xalapa. G. Rosas, 13/06/1995, CB403-1; G. Heredia, 30/ 03/2001, CB807, on dead branches.

Geographical distribution and substrate known: Didymostilbe capsici have been collected in Ecuador, Gold Coast (Seifert, 1985), Peru (Matsushima, 1993) and Cuba (Mena-Portales et al., 2017), on dead leaves, petioles and branches.

Drumopama girisa Subram., 1957. Proceedings of the Indian National Science Academy, Part B. Biol. Sciences 46: 333.

Plate 2. Fig. 10, 10a

Synnemata scattered, erect, dark brown to pale brown, subhyaline towards the tip, up to 910 μm long × 15-42 μm wide at the base. Conidiophores septate, simple, straight, curved, bent or flexuous, smooth, become free above, markedly geniculate, varying lengths. Conidiogenous cells polyblastic, integrated, geniculate, denticulate. Conidia, singly and acrogenously, ovoid to subglobose, with a basal papilla, hyaline, smooth, 0-septate, 10-12 μm diam.

Taxonomic summary

Veracruz, Botanical garden F. J. Clavijero, Mpio. Xalapa, R. M. Arias, 30/ 03/2001, CB776-1, on decaying leaves.

Geographical distribution and substrate known: the type material of Drumopama girisa comes from India (Subramanian, 1957), latter was collected in Taiwan (Chang, 1989), Japan (Chang, 1989) and Cuba (Castañeda & Kendrick, 1990; Mena-Portales et al., 1995), always associated with decaying leaves.

Gangliostilbe costaricensis Mercado, Gené & Guarro, 1997. Nova Hedwigia 64 (3-4): 456.

Plate 2. Fig. 8, 8a

Synnemata scattered, erect, composed of closely aggregated parallel conidiophores, blackish brown to pale brown towards the tip, up to 850 μm long, and up to 160 μm wide at the base. Conidiophores septate, simple, straight, bent or flexuous, smooth, divergent in the apical region. Conidiogenous cells monoblastic, integrated, terminal. Conidia, singly and acrogenously, broadly obovoid, truncate at the base, smooth, 3-septate, pale brown to brown, 41-48 × 20-25 μm, and 4-6 μm wide at the base.

Taxonomic summary

Veracruz, San Martín Tuxtla Volcano, Mpio. San Andrés Tuxtla, G. Heredia, 5/01/11, CB1940, CB2013, on dead branches.

Comments: synnemata in the Mexican material are longer and wider than those reported by Mercado-Sierra et al. (1997) from Costa Rica (250-450 × 60 μm).

Geographical distribution and substrate known: Gangliostilbe costaricensis has been registered only for the Neotropical region, the type specimen was collected on rotten wood from Costa Rica (Mercado-Sierra et al., 1997), later was found in Brazil (Marques et al., 2008; Santa-Izabel & Gusmão, 2016) also on rotten wood and decaying leaves.

Hyalosynnema multiseptatum Matsush., 1975. Icon. microfung. Matsush. lect. (Kobe): 85.

Plate 3. Fig. 12, 12a

Synnemata scattered, erect, straw-colored to hyaline, up to 280 μm long, and up to 35 μm wide at the base. Conidiophores septate, simple, straight, bent or flexuous, smooth, hyaline. Conidiogenous cells monoblastic, integrated, terminal. Conidia, singly and acrogenously, cylindrical, ellipsoidal, truncate at the base, 5-septate, hyaline, 21-28 × 5-6 μm.

Taxonomic summary

Veracruz, Biol. Station “Los Tuxtlas”, Mpio. San Andrés Tuxtla, J. Mena-Portales, 23/11/93, CB137, on dead branches.

Geographical distribution and substrate known: the type material of Hyalosynnema multiseptatum was collected in Iriomote Island, Okinawa (Matsushima, 1975), later it was registered from Peru (Matsushima, 1993) and Taiwan on bark of dead branches (Kirschner et al., 2001).

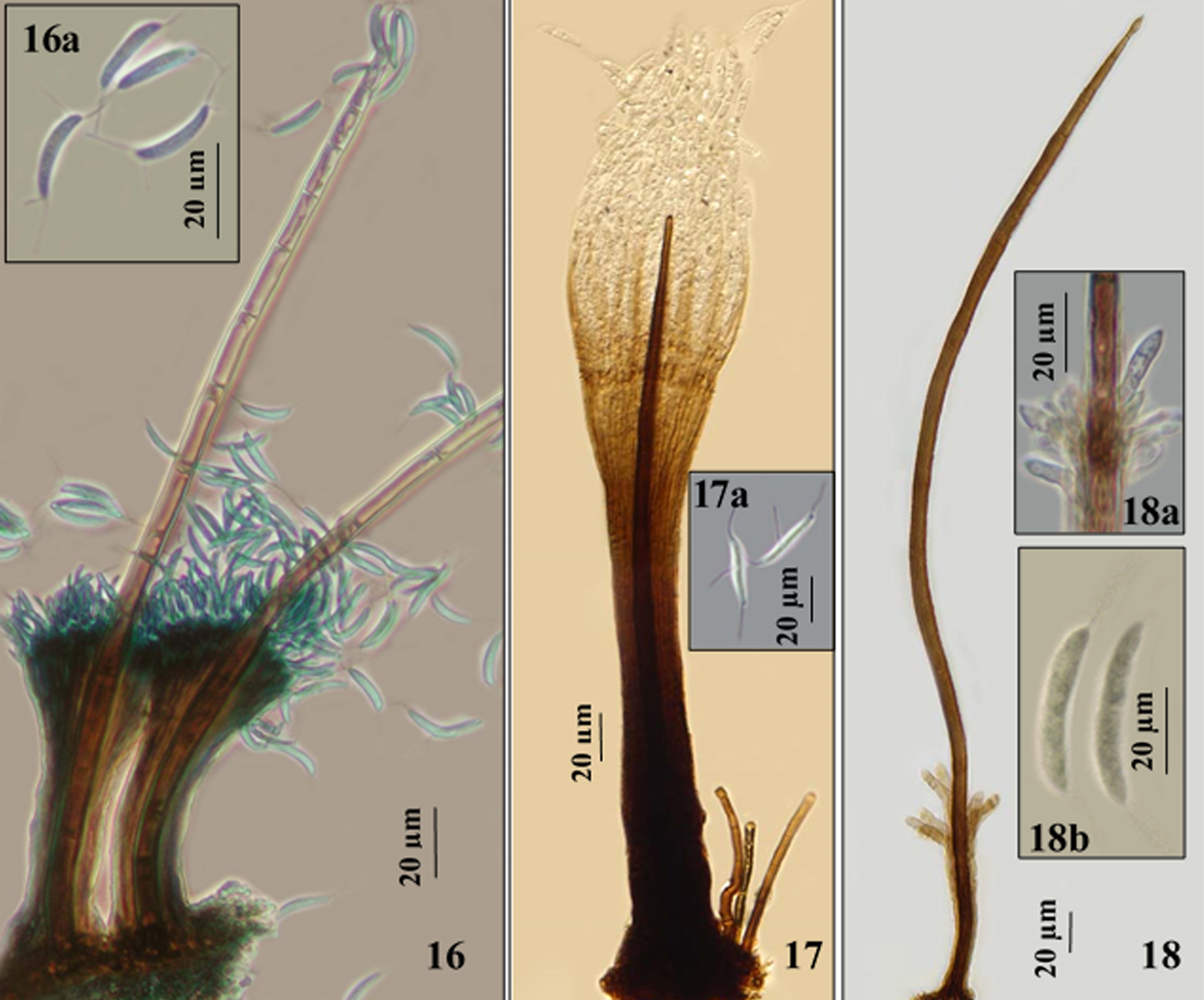

Menisporopsis anisospora R.F. Castañeda & Iturr., 2001. Cryptog. Mycol. 22 (4): 260.

Plate 4. Fig. 16, 16a

Synnemata erect, composed of closely aggregated parallel conidiophores surrounding a single seta, dark brown to blackish brown, up to 355 (whithout considering the seta lenght) and, up to 64 wide at the base. Conidiophores simple, straight, dark brown at the base, brown to pale brown towards the apex. Seta simple erect, straight, rounded at the apex, 300-386 × 8.5-9.5 μm. Conidiogenous cells phialidic, integrated, terminal. Conidia, aggregated in slimy masses, allantoid, fusiform, vermiform to irregular, 0-septate, hyaline, smooth, 18-30 × 2-6 μm, with 1-3 setulae, apical, eccentric and basal.

Taxonomic summary

Veracruz, San Martín Tuxtla Volcano, Mpio. San Andrés Tuxtla, G. Heredia, 05/01/11, CB1957, CB2015, on rachis of palm.

Geographical distribution and substrate known: this is the first report of M. anisospora since the species was described by Castañeda and Iturriaga from a petiole of decaying leaves collected on Venezuela (Castañeda-Ruiz et al., 2001).

Menisporopsis multisetulata K.M. Tsui, Goh, K.D. Hyde & Hodgkiss, 1999. Mycol. Res. 103 (2): 150.

Plate 4. Fig. 17, 17a

Synnemata erect, composed of closely aggregated parallel conidiophores surrounding a single seta, dark brown to blackish brown, up to 110 μm long (whithout considering the seta lenght) and, up to 30 μm wide at the base. Conidiophores septate, simple, straight, dark brown at the base, brown to pale brown towards the apex. Seta simple erect, straight, rounded at the apex, up to 300 × 7-8 μm. Conidiogenous cells phialidic, integrated, terminal. Conidia, aggregated in slimy masses, allantoid, 0-septate, hyaline, 12-19 × 2.5-4 μm, with 5-6 setulae on each end.

Taxonomic summary

Veracruz, Biol. Station “Los Tuxtlas”, Mpio. San Andrés Tuxtla, G. Heredia, 08/02/06, CB812, on decaying leaves.

Comments: synnemata and setae in the Mexican material are shorter than those reported by Tsui et al. (1999) from the type material (180-220 μm × 22-40 μm and 500 μm × 6-10 μm respectively).

Geographical distribution and substrate known: this is a scarcely reported species, besides the type specimen collected on submerged wood from Lam Tsuen River from Hong Kong (Tsui et al., 1999), García-García et al. (2013) listed as part of the mycobiota of decomposing fallen leaves of Rinorea guatemalensis, from a rainforest in Tabasco state, Mexico. Since there was not back-up description with herbarium material from the species, the formal registration of Menisporopsis multisetula from Mexico is presented in this contribution. The present collection is the first record for this species in the Neotropical region.

Menisporopsis profusa Piroz. & Hodges, 1973. Can. J. Bot. 51(1): 164.

Plate 4. Fig. 18, 18a, b

Synnemata erect, composed of closely aggregated parallel conidiophores surrounding a single seta, dark brown to blackish brown, up to 120 μm long × 13-30 μm wide at the base (without considering the seta length). Conidiophores septate, simple, straight, dark brown at the base, brown to pale brown towards the apex. Seta simple erect, straight, rounded at the apex, up to 356 μm long × 7-9 μm wide. Conidiogenous cells phialidic, integrated, terminal. Conidia, aggregated in slimy masses, cylindrical, curved, aseptate, hyaline, smooth, 10-15 × 2-2.5, bearing at each end a single setula.

Taxonomic summary

Veracruz, San Martín Tuxtla Volcano, Mpio. San Andrés Tuxtla, G. Heredia, 05/01/11, CB1996, on dead branches.

Comments: as in the Brazilian material studied by Cruz et al. (2014), our specimens have longer and wider setae than those reported by Pirozynski and Hodges (150-250 × 4.6-6 μm) for the type material (Pirozynski & Hodges, 1973).

Geographical distribution and substrate known: the type specimen of Menisporopsis profusa was detected on fallen leaves of Persea borbonia from South Carolina, USA (Pirozynski & Hodges, 1973). It has been collected in Malasya (Cybernome, 2017) and Brazil (Marques et al. 2007; Cruz et al., 2014) on decaying leaves, stems and petioles.

Phaeoisaria clavulata (Grove) E.W. Mason & S. Hughes, 1953. Mycol. Pap. 56: 42.

Plate 3: Fig. 14, 14a

≡ Pachnocybe clavulata Grove, 1885, J. Bot. Lond, 30: 168.

≡ Graphium grovi Sacc., 1886, Syll. Fung. 4: 613.

Synnemata erect, straight or flexuous, dark brown to pale brown, up to 790 μm long × 20-36 μm wide at the base. Conidiophores, straight, splaying out at the apex and along the sides of the upper half or two thirds of each synnema, dark brown at the base, brown to pale brown towards the apex. Conidiogenous cells polyblastic, integrated, terminal, denticles, hyaline. Conidia spherical, hyaline, smooth, 0-septate, 1-2 μm diam.

Taxonomic summary

Veracruz, Tlaltetela, Mpio. Huatusco, G. Heredia, 16/ 06/1995, CB426-5, on dead branches. Veracruz, Agüita Fría, Mpio. San Andrés Tlalnehuayocan, G. Heredia, 07/02/2010, CB1864, CB1865, CB1869, on dead branches.

Geographical distribution and substrate known: Phaeoisaria clavulata has been widely collected in different European localities (Ellis, 1971; Révay, 1986). There are also reports from Malawi (Sutton, 1993), India (Rao & De Hoog, 1986; Sridhar & Sudheep, 2011), Malasya (Cybernome, 2017) and Pakistan (Abbas et al., 2013). It is considered a lignicolous species. The present collection is the first record for this species in the Neotropical region.

Phaeoisaria infrafertilis B. Sutton & Hodges, 1976. Nova Hedwigia 27 (1-2): 219.

Plate 3: Fig. 13, 13a, b

≡ Chryseidea africana Onofri, 1981. Mycotaxon 31(2): 333

Synnemata erect, straight, dark brown, up to 815 μm long × 20-40 μm wide at the base. Conidiophores, straight, brown to pale brown towards the apex. Conidiogenous cells polyblastic, integrated, terminal, with cylindrical truncate denticles, pale brown to hyaline. Conidia solitary, falcate, apex and base finally obtuse, hyaline to pale brown, smooth, 0-septate, 12.5-18 × 1.5-2 μm.

Taxonomic summary

Veracruz, Tlaltetela, Mpio. Tlaltetela, G. Rosas, 16/ 06/1995, CB459, CB471-1, on fallen leaves. Veracruz, Mesa de Yerba, Mpio. Acajete, G. Heredia, 05/12/2010 CB1912, on dead herbaceous stems. Veracruz, San Martín Tuxtla Volcano, Mpio. San Andrés Tuxtla, G. Heredia, 05/01/11, CB1968, CB1992, on dead leaves.

Comments: synnemata in studied material are longer and wider, and conidia smaller than those reported by Sutton and Hodges (1976) (setae up to 200 × 10 μm; conidia 19.5-22 × 2-3 μm).

Geographical distribution and substrate known: the type specimen was collected in Brazil on Eucalyptus sp. dead leaves (Sutton & Hodges, 1976). There are reports from Ivory Coast (Onofri et al. 1981), Brazil (Conceição & Marques, 2015; Cruz et al., 2007; Grandi, 1996), Mauritius (Dulymamode et al., 2001), Cuba and Venezuela (Castañeda-Ruiz et al., 2002). This species has been frequently found on decaying leaves.

Phaeoisaria sparsa B. Sutton, 1973. Mycol. Pap. 132: 87.

Plate 3. Fig. 15

Synnemata erect, straight, dark brown to pale brown, up to 895 μm long × 84 μm wide at the base. Conidiophores, straight, splaying out at the apex, branched towards the apices, brown to pale brown towards the apex. Conidiogenous cells polyblastic, integrated, terminal, with cylindrical truncate denticles, hyaline. Conidia solitary, fusiform, hyaline to pale brown, smooth, 0-septate and 1-septate, 10-16 × 2-3.5 μm.

Taxonomic summary

Veracruz, Biol. Station “Los Tuxtlas”, Mpio. San Andrés Tuxtla, A. Mercado, 20/05/94, CB271-1, on dead branches. Veracruz, Park “El Haya”, Mpio. Xalapa, E. Hernández, 26/03/95, CB328-2, on bark of Quercus. Veracruz, Tlaltetela, Mpio. Tlaltetela, G. Rosas, 16/ 06/1995, CB423-5, on dead branches. Veracruz, Ixhuacán de los Reyes, Mpio. Ixhuacán de los Reyes, A. Mercado, 04/03/1996, CB596-1, on dead branches.

Geographical distribution and substrate known: the type specimen was collected on bark from Canada (Sutton, 1973). There are reports from New Zealand (Hughes, 1978), Malaysia (Ho et al., 2001), Cuba (Cybernome, 2017) and Nepal (GBIF: http://www.gbif.org/). It is mainly a lignic species of terrestrial and aquatic environments.

Phragmocephala elliptica (Berk. & Broome) S. Hughes, 1979. N.Z. Jl. Bot. 17 (2): 164.

Plate 3. Fig. 11

≡ Monotospora elliptica Berkeley et Broome, Ann. & Mag., 1881. Nat. Hist. Ser. 5, 7: 130. (Notices of British Fungi No. 1909).

≡ Brachysporium ellipticum (Berk, et Br.) Massee, 1893. British Fungus Flora 3: 414.

≡ Endophragmia elliptica (Berk, et Br.) Ellis, 1959. Mycol. Papers 72: 20.

≡ Phragmocephala cookei Mason et Hughes, 1951. Naturalist, Leeds 838: 98.

Synnemata fasciculate, straight, dark brown to pale brown, up to 165 μm long × 40-61 μm μm wide at the base. Conidiophores, straight, splaying out at the apex, brown to pale brown towards the apex. Conidiogenous cells monoblastic, integrated, terminal, pale brown. Conidia solitary, acrogenous, ellipsoidal, smooth, unequally colored, 5-septate, cells at each end subhyaline or pale brown, central cells brown to dark brown, 32–43 μm × 18–25 μm wide in the broadest part, 9–11 μm wide at the truncate base.

Taxonomic summary

Veracruz, Mesa de Yerba, Mpio. Acajete, G. Heredia, 05/ 12/2010, CB1883, CB1883-1, CB1883-2, on decaying leaves.

Geographical distribution and substrate known: this species have been collected in several European localities from Great Britain, Belgium, Switzerland (Ellis, 1959), Czechoslovakia (Holubová-Jechová, 1986), Hungary (Révay, 1986) and Russia (Davydkina & Mel’nik, 1989). There are also registers from Japan (Matshushima, 1985), Puerto Rico (Mel’nik, 1998) and Bolivia (Arias et al., 2007). Common on dead stems and leaves.

Roigiella lignicola R.F. Castañeda. 1984. Rev. Jardín Bot. Nac. Univ. Habana 5(1): 64.

Plate 2. Fig. 9, 9a

Synnemata erect, straight, hyaline, up to 270 μm long × 12-21 μm wide at the base. Conidiophores, straight, flexuous, splaying out at the apex, hyaline. Conidiogenous cells polyblastic, integrated, terminal, with cylindrical truncate denticles, hyaline. Conidia solitary, obovoid, clavate, allantoid, hyaline, smooth, 1-septate, 11-17 × 2-3 μm.

Taxonomic summary

Veracruz, Agüita Fría, Mpio. San Andrés Tlalnehuayocán, G. Heredia, 07/02/10, CB1874, CB1875, on dead branches. Veracruz, San Martín Tuxtla Volcano, Mpio. San Andrés Tuxtla, G. Heredia, Veracruz, 05/01/11, CB1980, on dead branches.

Geographical distribution and substrate known: this is the first record of Roigiella lignicola since it was described from dead branches of Cecropia peltata collected in Cuba (Castañeda-Ruiz, 1984).

Account of the synnematous species recorded for Mexico: 22 species of synnematous hyphomycetes belonging to 18 genera have been previously recorded for Mexico (Table 1). We found information only for the states of Chiapas (1), Tabasco (6), Tamaulipas (1) and Veracruz (17), and almost in all the cases, the records are scarce. Most materials have been collected from rain forest and cloud forest localities. In total, combined with the present contribution, to date 40 species belonging to 28 genera of synnematous microfungi have been documented for Mexico.

Discussion

All material analyzed in this contribution corresponded to asexual morphs. A limited number of studies have linked synnematous microfungi with their sexual morphs, based on either on direct evidence or by phylogenetic inferences from molecular data (i.e., Lombard et al., 2016; Rossman et al., 2001). Molecular studies of some synnematous species of the genera Vamsapriya Gawas & Bhat, Myrothecium Tode, Pseudocercospora Speg. and Graphium Corda, have led to their association with Xylariales, Hypocreales, Capnodiales and Microascales, respectively (Crous et al., 2006; Dai et al., 2014; Lombard et al., 2016; Okada et al., 1998).

In recent decades, molecular tools have allowed the phylogenetic relationships of many hyphomycetes to be inferred. Even so, in many cases, such as that of the present study, the lack of sufficient biological material from the natural substrates or the inability to obtain strains in artificial cultures, complicate the application of such tools. Thus, in view of the huge diversity and economical importance of hyphomycetes, the use of morphological characters for their identification remains necessary.

Approximately 135 genera of conidial microfungi with synnematous conidiomata have been described (Seifert et al., 2011), from these, 28 have been documented in the Mexican mycobiota. As well as the rest of the saprobic conidial microfungi, synnematous species are still essentially unexplored in Mexico. In the face of the extensive human impact and rapid habitat loss of tropical and semitropical Mexican regions, where it is assumed that there is the greatest fungal diversity (Rossman, 1997), it is urgent to promote studies to explore the diversity of these important microorganisms.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Biol. Magda Gómez Columna and M. Sc. Yamel Perea Rojas for their efficient help in searching bibliographic information and technical assist. Funding for this research was provided by the National Commission for Knowledge and Used of Biodiversity (Conabio) of Mexico through the financial support of the projects P030, B139 & IE004. RFCR is grateful to OSDE, Grupo Agrícola from Cuban Ministry of Agriculture for facilities.

Table 1

Synnematous species registered from Mexico.

|

Species |

Vegetation substrate |

State |

References |

|

Species |

Vegetation substrate |

State |

References |

|

Atractilina biseptata R.F. Castañeda |

RF/fallen leaves |

Ch |

Heredia et al., 2000a |

|

Arthrobotryum stilboideum Ces. |

CF/dead branches |

V |

This contribution |

|

Bactrodesmium longisporum M.B. Ellis |

CF/dead branches |

V |

This contribution |

|

Blastocatena pulneyensis Subram. & Bhat |

RF/dead rachis of palm |

V |

This contribution |

|

Cephalotrichum microsporum (Sacc.) P.M. Kirk |

CF/dead branches |

V |

This contribution |

|

Cephalotrichum purpureofuscum (S. Hughes) S. Hughes |

CF/dead branches |

V |

This contribution |

|

Coremiella cubispora (Berk. & M.A. Curtis) M.B. Ellis |

CF/rot wood |

V |

This contribution |

|

Dendrographium atrum Massee |

RF/dead branches |

V |

Heredia et al., 1997a |

|

Didymostilbe capsici (Pat.) Seifert |

CF/dead branches |

V |

This contribution |

|

Didymobotryum verrucosum I. Hino & Katum. |

RF/dead bamboo stalk |

Tb |

Becerra et al., 2008 |

|

Drumopama girisa Subram. |

CF/decaying leaves |

V |

This contribution |

|

Exophiala calicioides (Fr.) G. Okada & Seifert |

RF/dead branches & rotten wood |

V |

Heredia et al., 1997b |

|

Exosporium monanthotaxis Piroz. |

RF/dead branches |

V |

Heredia et al., 1997b |

|

Gangliostilbe costaricensis Mercado, Gené & Guarro |

CF/dead branches |

V |

This contribution |

|

Graphium penicillioides Corda |

RF/fallen leaves |

Tb |

Heredia et al., 2006 |

|

Hyalosynnema multiseptatum Matsush. |

RF/dead branches |

V |

This contribution |

|

Melanographium cookei M.B. Ellis |

RF/dead branches |

V |

Heredia et al., 1997a |

|

Melanographium selenioides (Sacc. & Paol.) M.B. Ellis |

CF/dead stems |

V |

Delgado-Rodríguez et al., 2006 |

|

Menisporopsis anisospora R.F. Castañeda & Iturr. |

CF/dead rachis of palm |

V |

This contribution |

|

Menisporopsis novae-zelandiae S. Hughes & W.B. Kendr. |

CF/fallen leaves |

V |

Arias et al., 2010 |

|

Menisporopsis multisetulata K.M. Tsui, Goh, K.D. Hyde & Hodgkiss |

RF/decaying leaves |

V |

This contribution |

|

Menisporopsis pirozynskii Varghese & V.G. Rao |

CF/fallen leaves |

V |

Heredia et al., 2000b |

|

Menisporopsis profusa Piroz. & Hodges |

CF/dead branches |

V |

This contribution |

|

Menisporopsis theobromae S. Hughes |

RF, CF/dead branches & leaves |

Tb, V Tm |

Heredia, 1994, Heredia et al., 1997b, Heredia et al., 2006 |

|

Neosporidesmium maestrense Mercado & J. Mena |

RF/dead branches |

V |

Heredia et al., 1997b |

|

Nodulisporium gregarium (Berk. & M.A. Curtis) J.A. Mey. |

RF/decaying wood |

V |

Heredia et al., 1997b |

|

Penicillium duclauxii Delacr. |

CF/soil forest |

V |

Heredia et al., 2011 |

|

Penicillium vulpinum (Cooke & Massee) Seifert & Samson |

CF/soil from forest & coffee plantation |

V |

Heredia et al., 2011 |

|

Phaeoisaria clavulata (Grove) E.W. Mason & S. Hughes |

CF/dead branches |

V |

This contribution |

|

Phaeoisaria clematidis (Fuckel) S. Hughes |

RF/dead branches & leaves |

Tb, V |

Heredia et al., 1997b, Heredia et al., 2006 |

|

Phaeoisaria infrafertilis B. Sutton & Hodges |

RF,CF/dead leaves & branches |

V |

This contribution |

|

Phaeoisaria sparsa B. Sutton |

RF/dead branches |

V |

This contribution |

|

Phalangispora nawawii Kuthub. |

CF/submerged leaves |

V |

Heredia et al., 2000b |

|

Phragmocephala atra (Berk. & Broome) E.W. Mason & S. Hughes |

CF/dead stems Musa sp. |

V |

Mercado-Sierra & Heredia,1994 |

|

Phragmocephala elliptica (Berk. & Broome) S. Hughes |

CF/decaying leaves |

V |

This contribution |

|

Roigiella lignicola R.F. Castañeda |

CF/dead branches |

V |

This contribution |

|

Synnemacrodictys stilboidea (J. Mena & Mercado) W.A. Baker & Morgan-Jones |

CF/dead branches |

V |

Heredia et al., 2000a |

|

Thozetella cristata Piroz. & Hodges |

RF/dead branches |

Tb |

Becerra et al., 2007 |

|

Tretopileus sphaerophorus (Berk. & M.A. Curtis) S. Hughes & Deighton |

RF/dead leaves & branches |

Tb, V |

Heredia et al., 2000a, Becerra et al., 2008 |

|

Virgatospora echinofibrosa Finley |

RF/dead branches |

V |

Heredia et al., 1997b |

State: Ch = Chiapas, Tb = Tabasco, Tm = Tamaulipas, V = Veracruz.

Vegetation: RF = rain forest, CF = cloud forest.

References

Abbas, S. Q., Mushtaq, S., & Abbas, A. (2013). Addition to the mycoflora on Szygium cumini from district Faisalabad, Pakistan. FUUAST Journal of Biology, 3, 39–43.

Arias, R. M., Heredia, G., & Mena-Portales, J. (2007). Primeros registros de hongos anamorfos (Hyphomycetes) colectados en restos vegetales del Parque Nacional Cotapata, La Paz, Bolivia. Boletín de la Sociedad Micológica de Madrid, 31, 157–169.

Arias, R. M., Heredia, G., & Mena-Portales, J. (2010). Adiciones al conocimiento de la diversidad de los hongos anamorfos del bosque mesófilo de montaña del estado de Veracruz III. Acta Botanica Mexicana, 90, 19–42.

Barbosa, F. R., & Gusmão, L. F. P. (2011). Conidial fungi from semi-arid Caatinga Biome of Brazil. Rare freshwater hyphomycetes and other new records. Mycosphere, 2, 475–485.

Becerra, H. C., Heredia, G., & Arias, R. M. (2007). Contribución al conocimiento de los hongos anamorfos saprobios del estado de Tabasco. II. Revista Mexicana de Micología, 24, 39–53.

Becerra, H. C., Heredia, G., Arias, R. M., Mena-Portales, J., & Castañeda-Ruiz, R. F. (2008). Los hongos anamorfos saprobios del estado de Tabasco. III. Revista Mexicana de Micología, 28, 25–39.

Cai, L., Zhang, K., McKenzie, E. H., & Hyde, K. D. (2003). Freshwater fungi from bamboo and wood submerged in the Liput River in the Philippines. Fungal Diversity, 13, 1–12.

Castañeda-Ruiz, R. F. (1984). Nuevos taxones de Deuteromycotina: Arnoldiella robusta gen. et sp. nov.; Roigiella lignicola gen. et sp. nov.; Sporidesmium pseudolmediae sp. nov. y Thozetella havanensis sp. nov. Revista del Jardín Botánico Nacional Universidad de la Habana, 5, 57–87.

Castañeda-Ruiz, R. F., Guerrero, B., Adamo, G. M., Morillo, O., Minter, D. W., Stadler, M. et al. (2009). A new species of Selenosporella and two microfungi recorded from a cloud forest in Mérida, Venezuela. Mycotaxon, 109, 63–74.

Castañeda-Ruiz, R. F., & Günter, R. W. A. (1985). Deuteromycotina de Cuba. I. Hyphomycetes. Revista del Jardín Botánico Nacional, 6, 47–67.

Castañeda-Ruiz, R. F., Heredia, G., Gusmão, L. F. P., & Li, D. W. (2016). Fungal diversity of Central and South America. In D. W. Li (Ed.), Biology of Microfungi (pp. 197–217). China: Springer International Publishing.

Castañeda-Ruiz, R. F., Iturriaga, T., Saikawa, M., Cano, J., & Guarro, J. (2001). The genus Menisporopsis in Venezuela with the addition of M. anisospora anam. sp. nov. from a palm tree. Cryptogamie Mycologie, 22, 259–263.

Castañeda-Ruiz, R. F., & Kendrick, B. (1990). Conidial fungi from Cuba: I. University of Waterloo, Biology Series, 3, 1–53.

Castañeda-Ruiz, R. F., Velázquez, S., Cano, J., Saikawac, M., & Guarro, J. (2002). Phaeoisaria aguilerae anam. sp. nov. from submerged wood in Cuba with notes and reflections in the genus Phaeoisaria. Cryptogamie Mycologie, 23, 9–18.

Chang, H. S. (1989). Six synnematous hyphomycetes new for Taiwan. Botanical Bulletin of Academia Sinica, 30, 161–166.

Chavan, P. B., & Bhambure, G. B. (1975). A rust on ground nut (Arachis hypogaea L.) from Maharashtra State, India. Maharashtra Vidnyan Mandir Patrika, 10, 1–2.

Conceição, L., & Marques, M. (2015). A preliminary study on the occurrence of microscopic asexual fungi associated with bird nests in Brazilian semi-arid. Mycosphere, 6, 274–279.

Crous, P. W., Slippers, B., Wingfield, M. J., Rheeder, J., Marasas, W. F., Philips, A. J. et al. (2006). Phylogenetic lineages in the Botryosphaeriaceae. Studies in Mycology, 55, 235–253.

Cruz, A. C. R., Marques, M. F. O., & Gusmão, L. F. P. (2007). Fungos anamórficos (Hyphomycetes) da Chapada Diamantina: novos registros para o Estado da Bahía e Brasil. Acta Botanica Brasilica, 21, 847–855.

Cruz, A. C. R., Marques, M. F. O., & Gusmão, L. F. P. (2014). Conidial fungi from the semi-arid Caatinga biome of Brazil: The genus Menisporopsis. Acta Botanica Brasilica, 28, 339–345.

Cybernome, the Nomenclator for Fungi and their Associated Organisms [Access in 27 march 2017]. Available at: http://www.cybertruffle.org.uk/cybernome/eng

Cybertruffle’s Robigalia, Observations of fungi and their associated organisms [Access in 22 March 2017]. Available at: http://www.cybertruffle.org.uk/robigalia/eng/

Dai, D. Q., Bahkali, A. H., Li, Q. R., Bhat, D. J., Wijayawardene, N. N., Li, W. J. et al. (2014). Vamsapriya (Xylariaceae) re-described, with two new species and molecular sequence data. Cryptogamie Mycologie, 35, 339–357.

Davydkina, T. A., & Mel’nik, V. A. (1989). Hyphomycetes new for the USSR from subterranean excavations in North Ossetia and Primorsky krai. Mikologiya/ Fitopatologiya, 23, 409–411.

Delgado, G., Heredia, G., Arias, R. M., & Mena-Portales, J. (2006). Contribución al estudio de los hongos anamórficos de México. Nuevos registros para el estado de Veracruz. Boletín de la Sociedad Micológica de Madrid, 30, 235–242.

Domsch, K. H., Gams, W., & Anderson, T. H. (1980). Compendium of soil fungi. Volume 1. London: Academic Press.

Dulymamode, R., Cannon, P. F., & Peerally, A. (2001). Fungi on endemic plants of Mauritius. Mycological Research, 105, 1472–1479.

Ellis, M. B. (1959). Clasterosporium and some allied dematiaceae-phragmosporae. II. Mycological Papers, 72, 1–75.

Ellis, M. B. (1971). Dematiaceous Hyphomycetes. Surrey, England: Commonwealth Mycological Institute, Kew.

Ellis, M. B. (1976). More dematiaceous Hyphomycetes. Surrey, England: Commonwealth Mycological Institute, Kew.

Figueroa, R., Bran, M. C., Morales, O., & Castañeda-Ruiz, R. (2016). Nuevos registros de hongos anamórficos para Guatemala. Revista Científica de la Facultad de Ciencias Químicas y Farmacia, 26, 40–50.

García-García, M. A., Heredia, G., Cappello, G. S., & Rosique-Gil, E. (2013). Analysis of the sporulating microfungal community in decomposing fallen leaves of Rinorea guatemalensis (Wats.) Bartlett (Malphigiales, Violaceae) in a Mexican rainforest. Cryptogamie Mycologie, 34, 99–111.

Gharizadeh, K. H., Sheykholeslami, A., & Khodaparast, S. A. (2007). A study on the identification of wood inhabiting hyphomycetes in Chalus vicinity (Iran). Rostaniha, 8, 30–32.

Global Biodiversity Information Facility [Access in 5 May 2017]. Avaible at: http://www.gbif.org/

Grandi, R. A. P. (1996). Hyphomycetes on Alchornea triplinervia (Spreng.) Muell. Arg. leaf litter from the Ecological Reserve Juréia-Itatins, State of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Mycotaxon, 60, 373–386.

Gusmão, L. F. P., & Grandi, R. A. P. (1997). Hyphomycetes com conidioma dos tipos esporodóquio e sinema associados a folhas de Cedrela fissilis (Meliaceae), em Maringá, Pr, Brasil. Acta Botanica Brasilica, 11, 123–134.

Heredia, G. (1994). Hifomicetes dematiáceos en el bosque mesófilo de montaña. Registros nuevos para México. Acta Botanica Mexicana, 27, 15–32.

Heredia, G., Arias, R. M., & Gómez, S. (2011). Hongos microscópicos: especies en restos vegetales y del suelo. In A. Cruz-Angón (Eds.), La biodiversidad en Veracruz estudio de estado. Volumen II (pp. 41–49). México: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento de la Biodiversidad/ Gobierno del Estado de Veracruz/ Universidad Veracruzana/ Instituto de Ecología, A.C.

Heredia, G., Arias, R. M., & Reyes, M. (2000a). Contribución al conocimiento de los hongos Hyphomycetes de México. Acta Botanica Mexicana, 51, 39–51.

Heredia, G., Arias, R. M., & Reyes, M. (2000b). Leaf litter fungi. Eight setose conidial species unknown from Mexico. Revista Mexicana de Micología, 16, 17–25.

Heredia, G., Castañeda-Ruíz, R., Becerra, H. C., & Arias, R. M. (2006). Contribución al conocimiento de los hongos anamorfos saprobios del estado de Tabasco. I. Revista Mexicana de Micología, 23, 53–62.

Heredia, G., Mena-Portales J., & Mercado-Sierra, A. (1997a). Hyphomycetes saprobios tropicales. Nuevos registros de Dematiáceos para México. Revista Mexicana de Micología, 13, 41–51.

Heredia, G., Mena-Portales, J., Mercado-Sierra, A., & Reyes M. (1997b). Tropical hyphomycetes of Mexico. II. Some species from the Tropical Biology Station” Los Tuxtlas”, Veracruz, Mexico. Mycotaxon, 64, 203–223.

Ho, W. H., Hyde, K. D., & Hodgkiss, I. J. (2001). Fungal communities on submerged wood from streams in Brunei, Hong Kong, and Malaysia. Mycological Research, 105, 1492–1501.

Holubová-Jechová, V. (1986). Lignicolous Hyphomycetes from Czechoslovakia 8. Endophragmiella and Phragmocephala. Folia Geobotanica y Phytotaxonomica, 21, 173–197.

Hughes, S. J. (1978). New Zealand fungi 25. Miscellaneous species. New Zealand Journal of Botany, 16, 311–370.

Huseyin, E., Selcuk, F., & Bulbul, A. S. (2011). New records of microfungal genera from Mt. Strandzha in Bulgaria (south-eastern Europe). II. Mycologia Balcanica, 8, 157–160.

Jong, S. C., & Morris, E. F. (1968). Studies on the synnematous fungi imperfecti-III. Phaeoisariopsis. Mycopathologia et Mycologia Applicata, 34, 263–272.

Kapoor, J. N., & Munjal, R. L. (1966). Indian species of Stilbaceae. Indian Phytopathology, 19, 346–356.

Kendrick, B. (2001). The fifth kingdom. Focus Information Group. Waterloo: Mycologue Publications.

Kirschner, R., Chen, Z. C., & Oberwinkler, F. (2001). New records of ten species of Hyphomycetes from Taiwan. Fungal Science, 16, 47–62.

Landcare Research Manaaki Whenua [Access in 1 April 2017]. Available at: http://nzfungi.landcareresearch.co.nz/html/search_index.asp

Lombard, L., Houbraken, J., Decock, C., Samson, R. A., Meijer, M., Réblová, M. et al. (2016). Generic hyper-diversity in Stachybotriaceae. Persoonia, 36, 156–246.

Marques, O. M. F., de Moraes J. O. V., Santos, L. M. S., Gusmão, L. F. P., & Maia, L. C. (2007). Fungos conidiais lignícolas em um fragmento de Mata Atlântica, Serra da Jibóia, BA. Revista Brasileira de Biociências, 5, 1186–1188.

Marques, O. M. F., Gusmão, L. F. P., & Maia, L. C. (2008). Riqueza de espécies de fungos conidiais em duas áreas de Mata Atlântica no Morro da Pioneira, Serra da Jibóia, BA, Brasil. Acta Botanica Brasilica, 22, 954–961.

Matsushima, T. (1975). Icones Microfungorum a Matsushima Lectorum. Japan: Kobe.

Matsushima, T. (1985). Matsushima Mycological Memories No. 4. Japan: Kobe.

Matsushima, T. (1993). Matsushima Mycological Memories No. 7. Japan: Kobe.

Mel’nik, V. A. (1998). Some notes on Deuteromycetes from tropical countries. IV. Mikologiya I Fitopatologiya, 32, 32–43.

Mena-Portales, J., Delgado, R. G., Hernández, G. A., González, F. G., & Mercado-Sierra, A. (2017). Hifomicetes de Sierra de Cubitas, Cuba. Acta Botánica Cubana, 216, 17–30.

Mena-Portales, J., López, M. O., Mercado-Sierra, A., Hernández, G. A., Sandoval, R., Rodríguez, M. K. et al. (1995). Adiciones a la micobiota de la caña de azúcar (Saccharum sp. híbrida) en Cuba. I. Hifomicetos. Revista Iberoamericana de Micología, 12, 31–35.

Mercado-Sierra, A., Gené, J., & Guarro, J. (1997). Some Costa Rican hyphomycetes. I. Nova Hedwigia, 64, 455–466.

Mercado-Sierra, A., & Heredia, G. (1994). Hyphomycetes, asociados a restos vegetales en el estado de Veracruz, México. Revista Mexicana de Micología, 10, 33–48.

Morris, E. F. (1963). The synnernatous genera of the fungi imperfecti. Western Illinois University, Series in the Biological Sciences, 3, 1–143.

Morris, E. F. (1966). Studies on the synnernatous fungi imperfecti. I. Mycopathologia et Mycologia Applicata, 28, 97–101.

Morris, E. F. (1967). Studies on the sinnematous fungi imperfecti II. Mycopathologia, 33, 179–185.

Morton, F. J. & Smith, G. (1963). The genera Scopulariopsls Bainier, Microascus Zukal, and Doratomyces Corda. Mycological Papers, 86, 1–96.

Okada, G., Seifert, K. A., Takematsu, A., Yamaoka, Y., Miyazaki, S., & Tubaki, K. (1998). A molecular phylogenetic reappraisal of the Graphium complex based on 18S rDNA sequences. Canadian Journal of Botany, 76, 1495–1506.

Onofri, S., Lunghini, D., Rambelli, A., & Lustrati, L. (1981). New dematiaceous hyphomycetes from tropical rain forest litter [Ivory Coast]. Mycotaxon, 13, 331–338.

Pirozynski, K. A., & Hodges, C. S. (1973). New Hyphomycetes from South Carolina. Canadian Journal of Botany, 51, 157–173.

Prasher, I. B., & Singh, G. (2013). Two hyphomycetes new to India. Journal on New Biological Reports, 2, 231–233.

Rao, V., & de Hoog, G. S (1986). New or critical hyphomycetes from India. Studies in Mycology, 28, 1–84.

Révay, Á. (1986). Dematiaceous Hyphomycetes inhabiting forest debris in Hungary II. Studia Botanica Hungarica, 19, 73–78.

Rong, I. H., & Botha, A. (1993). New and interesting records of South African Fungi XII. Synnematous Hyphomycetes. South African Journal of Botany, 59, 514–518.

Rossman, A. (1997). Biodiversity of tropical Microfungi: an overview. In K. D. Hyde (Ed.), Biodiversity of tropical Microfungi (pp. 1–10). Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Rossman, A., McKemy, J. M., & Pardo-Schultheiss, R. A. (2001). Molecular studies of the Bionectriaceae using large subunit rDNA sequences. Mycologia, 93, 100–110.

Santa Izabel, T. D. S., & Gusmão, L. F. P. (2016). Fungal succession on plant debris in three humid forests enclaves in the Caatinga biome of Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Botany, 39, 1065–1076.

Seifert, K. A. (1985). A monograph of Stilbella and some allied Hyphomycetes. Studies in Mycology, 27, 1–166.

Seifert, K. A. (1990). Synnematous Hyphomycetes. Memoirs of the New York Botanical Garden, 59, 109–154.

Seifert, K. A., Morgan-Jones, G. Gams, W., & Kendrick, B. (2011). The genera of Hyphomycetes. CBS Biodiversity Series 9. Utrecht: CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre.

Sridhar, K. R., & Sudheep, N. M. (2011). The spatial distribution of fungi on decomposing woody litter in a freshwater stream, Western Ghats, India, Microbial Ecology, 61, 635–645.

Subramanian, C. V. (1957). Hyphomycetes-IV. Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences-Section B, 46, 324–335.

Subramanian, C. V., & Bhat, D. J. (1987). Hyphomycetes from South India. I some new taxa. Kavaka, 15, 41–74.

Sutton, B. C. (1973). Hyphomycetes from Manitoba and Saskatchewan, Canada. Mycological Paper, 132, 1–143.

Sutton, B. C. (1993). Mitosporic fungi from Malawi. Mycological Paper, 167, 1–94.

Sutton, B. C., & Hodges, C. S (1976). Eucalyptus microfungi. Microdochium y Phaeosaria species from Brasil. Nova Hedwigia, 27, 215–222.

Tikhomirova, I. N. (1989). Analysis of the species composition of micromycetes on the Rosaceae in Leningrad oblast. Mycology & Phytopathology, 23, 366–373.

Tsui, K.M., Goh, T. K., Hyde, K. D., & Hodgkiss, I. J. (1999). Reflections on Menisporopsis, with the addition of M. multisetulata sp. nov. from submerged wood in Hong Kong, Mycological Research, 103, 148–152.

USDA Fungal Databases [Access in 28 April 2017]. Available at: http://nt.ars-grin.gov/fungaldatabases

Vijaykrishna, D., & Hyde, K. D. (2006). Inter-and intra-stream variation of lignicolous freshwater fungi in tropical Australia. Fungal Diversity, 21, 203–224.

Virtual Fungal Dried Reference Collection of New York Botanic Garden [Access in 25 April 2017]. Available at: http://sciweb.nybg.org/Science2/vii2.asp

Wong, M. K., & Hyde, K. D. (2001). Diversity of fungi on six species of Gramineae and one species of Cyperaceae in Hong Kong. Mycological Research, 105, 1485–1491.