Incidence of galls on fruits of Parkinsonia praecox and its consequences on structure and physiology traits in a Mexican semi-arid region

Eliezer Cocoletzi a, Ximena Contreras-Varela a, b, María José García-Pozos c, Lourdes López-Portilla c, María Dolores Gaspariano-Machorro c, Juan García-Chávez c, G. Wilson Fernandes d, Armando Aguirre-Jaimes a, *

a Red de Interacciones Multitróficas, Instituto de Ecología, A.C., Carretera antigua a Coatepec 351, Congregación El Haya, 91070 Xalapa , Veracruz, Mexico 91070 Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico

b Universidad Veracruzana, Facultad de Biología, Circuito Gonzalo Aguirre Beltrán s/n, Zona Universitaria, 91090 Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico

c Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Facultad de Biología, Blvd. Valsequillo y Av. San Claudio, Ed. BIO 1, Ciudad Universitaria, Colonia Jardines de San Manuel, 72570 Puebla, Puebla, Mexico

d Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Departamento de Biologia Geral, Laboratório de Ecologia Evolutiva e Biodiversidade, Av. Antônio Carlos, 6627, Pampulha, 486 Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil

*Corresponding author: armando.aguirre@inecol.mx (A. Aguirre-Jaimes)

a Red de Interacciones Multitróficas, Instituto de Ecología, A.C., Carretera antigua a Coatepec 351, Congregación El Haya, 91070 Xalapa , Veracruz, Mexico 91070 Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico

b Universidad Veracruzana, Facultad de Biología, Circuito Gonzalo Aguirre Beltrán s/n, Zona Universitaria, 91090 Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico

c Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Facultad de Biología, Blvd. Valsequillo y Av. San Claudio, Ed. BIO 1, Ciudad Universitaria, Colonia Jardines de San Manuel, 72570 Puebla, Puebla, Mexico

d Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Departamento de Biologia Geral, Laboratório de Ecologia Evolutiva e Biodiversidade, Av. Antônio Carlos, 6627, Pampulha, 486 Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil

*Corresponding author: armando.aguirre@inecol.mx (A. Aguirre-Jaimes)

Abstract

Galls are atypical plant growths that provide nourishment, shelter, and protection to the inducer or its progeny. Fruit and flowers are poorly represented as host organs for galling insects. Our main question was: Do morphological traits, anatomical features and physiological characteristics differ between galled and healthy fruits of Parkinsonia praecox? Galled and healthy fruits of P. praecox were characterized in terms of morphological traits (length, diameter, thickness, water and biomass content); anatomical features (trichomes, stomatal and pavement cells), and physiological characteristics (stomatal conductance, gs). We found that galled fruits were induced by Asphondylia sp. (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae). Thickness, diameter, and water content values of galled fruits were greater compared to healthy fruits. Length, biomass, and pavement cells density of healthy fruits were higher. The density of trichomes on galled fruits was higher, while the stomatal density and pavement cell size were not statistically different between galled and healthy fruits. Furthermore, the gs rates of galled fruits were almost 3 times higher than in healthy fruits. Incidence of galls on fruits on P. praecox modified the original morphology and anatomy of healthy fruits that stimulate physiological mechanisms to increase the water continuum from the host plant to the gall.

Keywords:

Fabaceae; Pods; Galling insects; Dipteran; Morphology

© 2019 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. Este es un artículo Open Access bajo la licencia CC BY-NC-ND

Incidencia de agallas en frutos de Parkinsonia praecox y sus consecuencias sobre atributos morfológicos y fisiológicos en una zona semiárida de México

Resumen

Las agallas son estructuras complejas de las plantas que presentan crecimiento anormal y proveen alimento, refugio y protección al organismo inductor. Flores y frutos están escasamente reportados como órganos hospederos. Nuestra pregunta central fue: ¿los atributos morfológicos, anatómicos y fisiológicos, difieren entre frutos con agallas y sanos de Parkinsonia praecox? Los frutos con agallas y sanos fueron caracterizados en términos de atributos: morfológicos (longitud, diámetro, grosor, contenido de agua y biomasa); anatómicos (tricomas, estomas y células del pavimento) y fisiológicos (conductancia estomática, gs). Encontramos que los frutos con agallas son inducidos por Asphondylia sp. (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae). El grosor, diámetro y contenido de agua fue mayor en frutos con agallas. La longitud, biomasa y densidad de células del pavimento fue mayor en frutos sanos. La densidad de tricomas en frutos con agallas fue mayor, pero la densidad de estomas y el tamaño de las células del pavimento no presentaron diferencias. La gs de los frutos con agallas fue 3 veces mayor que en los sanos. La incidencia de agallas en frutos de P. praecox modifica la morfología y anatomía original de éstos, estimulando mecanismos fisiológicos que incrementan el continuo de agua de la planta hospedera hacia la agalla.

© 2019 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license

Palabras clave:

Fabaceae; Vainas; Insectos agalladores; Díptero; Morfología

Introduction

Estimates of galling insect richness calculates ~133,000 species distributed around the world (Espírito-Santo & Fernandes, 2007). The galling habit is widely spread among insects and is mostly comprised of Diptera, Hymenoptera, Hemiptera, Thysanoptera, Lepidoptera, and Coleoptera (Fernandes & Carneiro, 2009). These organisms induce abnormal structures on the plant, known as galls, cecidias or plant tumors (Fernandes & Carneiro, 2009). These structures are composed of plant tissue characterized by the increase in the number of cells (hyperplasy) and/or the increase in cell size (hypertrophy) (Mani, 1964).

Galls can be induced on any vegetative structure (leaves, stems, branches and roots) or reproductive organ (flowers, fruits and seeds) (Mani, 1964). The growth mechanisms of the plant organs are modified in response to stimuli from the galling insects (e.g., salivary secretion during feeding or maternal secretion in the oviposition), which alters the architecture and physiology of the plant in order to benefit it or its progeny (Oliveira et al., 2016; Raman, 2007; Stone & Schönrogge, 2003). The gall provides food, shelter, and protection against natural enemies for the galling insects (Fernandes & Santos, 2014; Price et al., 1987; Stone & Schönrogge, 2003).

Galling insects are found on specific host plants in natural communities across most biogeographical regions (Fernandes & Price, 1991; Price et al., 1998). However, their species richness has been reported to be higher in tropical regions (Fernandes & Price, 1988; Gonçalves-Alvim & Fernandes, 2001), with more species ocurring in xeric environments (Price et al., 1998) than in temperate and cold regions. At the global scale, most studies addressing the richness of galling insects have been carried out in the Cerrado (Brazilian savanna) (Araújo et al., 2014; Carneiro et al., 2009; Coelho et al., 2009; Fernandes et al., 1997; Gonçalves-Alvim & Fernandes, 2001), but also in tropical savanna (Blanche, 2000) and humid subtropical forests (Blanche & Westoby, 1995) in Australia, tropical humid and dry forests in Panama (Medianero et al., 2003) and in montane forest and shrublands in Texas, USA (Blanche & Ludwing, 2001). In Mexico, there is a scarcity of research studies on the ecology of galling insects. There are only a few studies reporting galling insect richness in 2 tropical rainforests (Los Tuxtlas Biosphere Reserve and in Lacandonia rainforest; Oyama et al., 2003) and in a tropical dry forest (Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve; Cuevas-Reyes et al., 2004).

Buds, flowers, and fruits are poorly represented as host organs for galling insects, since these structures depend on the phenological stage of the plant (i.e., they may be unavailable to gallers throughout the year). The phenological dependence is more evident in tropical dry forests and xeric environments (Pezzini et al., 2014). Despite the low number of studies reporting galls on reproductive organs (Fernandes & Santos, 2014), the effects of galling on these organs could pose serious threats to the plants due to the potential impact they would have on plant performance and fitness (Fernandes, 1987). Galls on fruits exhibit noteworthy morphotypes, such as irregular (Santos et al., 2016), spherical (Quintero et al., 2014), amorphous, fusiform, globoid, ovoid, swollen or triangular (Isaias et al., 2014).

The impact of galling insects on their host plants is variable. Galling insects are known to stimulate the metabolism of nearby sources by increasing the sink demand relative to source supply (Fay et al., 1993). This leads to negative effects on the plant, such as a reduction in branch length (Fernandes et al., 1993; Kurzfeld-Zexer et al., 2010; Silva et al., 1996), lower quality seeds that affect germination (Santos et al., 2016; Silva et al., 1996), decrease in CO2 assimilation (Haiden et al., 2012; Larson, 1998), limitations on flower and fruit production (Fernandes et al., 1993; Silva et al., 1996), and a reduction of entire plant biomass (McCrea et al., 1985). Galls on leaves of Acer sacharum (Sapindaceae) diminish approximately 60% of the stomatal conductance (Patankar et al., 2011). In contrast, the stomatal conductance of leaf galls on Acacia longifolia (Mimosoideae) shows no change in response to light intensity, but the immature galls had higher rates of stomatal conductance (Haiden et al., 2012). To our knowledge, beyond these reports, there are no studies that quantify the stomatal conductance in fruit with galls. Since these structures are physiological sinks and could have a negative effect on the fruit set, studies related to fruit galls become particularly important in order to understand how the presence of galls affects the reproductive input and fitness of the plant. The approach of this study involves the anatomical and physiological features in galled and healthy fruits.

We investigated the effects of galls on fruits of Parkinsonia praecox (Ruiz & Pav. ex Hook.) Hawkins based on morphological traits (length, diameter, thickness, water content and biomass content); anatomical features (trichomes, stomatal, and pavement cells), and physiological characteristics (stomatal conductance, gs).

Materials and methods

The study was conducted in the Zapotitlán Salinas Valley, located in the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Biosphere Reserve, Puebla, Mexico. The data sampling was carried out in the nearby surroundings of the “Helia Bravo-Hollis” Botanical Garden (18°20’ N, 97°28’ W, at 1,500 m asl). The main plant association is the tetechera, dominated by the columnar cactus Neobuxbaumia tetetzo (Zavala, 1982); the vegetation corresponds to semi-arid scrubland (Rzedowski, 2006). The mean annual precipitation is 381.21 mm, and the annual mean temperature is 18.04 °C. The dry season is from September to April, and the rainy season is from May to August (Zavala, 1982). The climatic data were obtained from Conagua (2010) for the period 1964-2010.

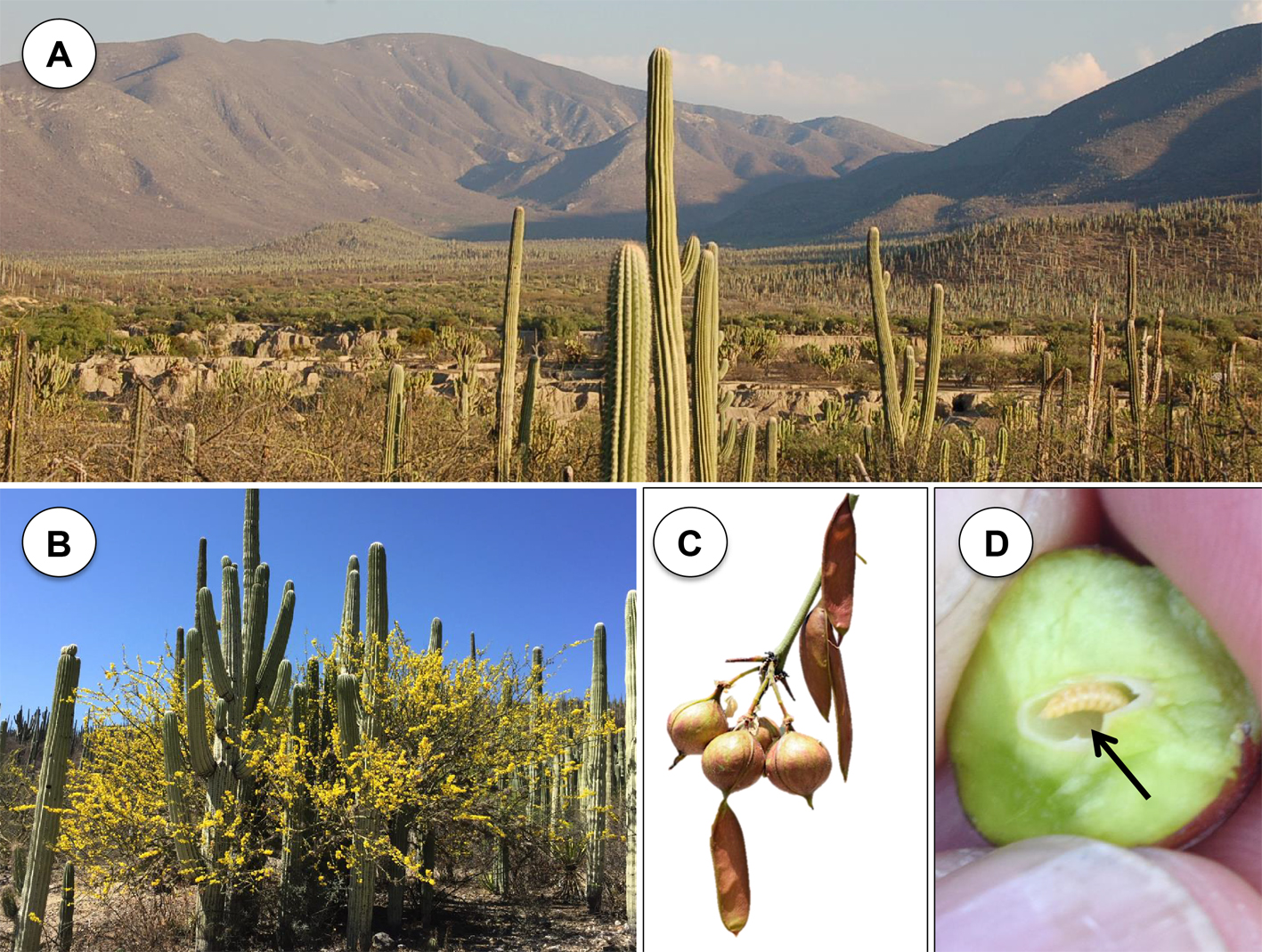

Parkinsonia praecox (Fabaceae-Caesalpinoideae) is known in the study area as “manteco” or “palo verde”, it is a 7 m tall tree (Fig. 1A). In Mexico, it is distributed in the Northwest (Baja California Sur, Sonora, Chihuahua, Sinaloa, Durango, Zacatecas and Nayarit), East Center (Jalisco, Colima, Michoacán, Guanajuato, Morelos, Guerrero, Puebla, México), East (Tamaulipas and Veracruz), and South (Oaxaca and Chiapas) (Villaseñor, 2016). It is a common species in some vegetal associations in the Zapotitlan Salinas Valley (López-Galindo et al., 2003; Montaña & Valiente-Banuet, 1998). P. praecox fruits are flattened brown pods 10 cm length and 1 cm width, arranged in racemes, generally in pairs (Fig. 1B). Seeds are shiny-brown color and 7 mm mean length (Pennington & Sarukhán, 2005). The flowering season occurs between December-May, and the fruiting period is between January-September (Arias et al., 2001; Pennington and Sarukhán, 2005). Infructescences of P. praecox showed an important incidence of galls (Fig. 1C). Galled fruits had 1 larval chamber located at the center surrounded by parenchymatous tissue (Fig. 1D) (Contreras-Varela pers. obs.). Asphondylia sp. (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) is the galling insect. From November to March, the branches are leafless when flowering and fruit set occurs (Pavón & Briones, 2001), indicating that it is a totally deciduous species during this period.

The number of fruits affected by galls was determined in 30 randomly selected branches with galls and fruits of 50 cm long (2 per tree) in 15 different trees. In 10 individuals of P. praecox it was determined macroscopical characteristics of galled and healthy fruits, 50 pairs of a galled and a healthy fruit were randomly selected. A digital caliper (CD-s6, Mitutoyo Corp., Kawasaki, Japan) was used to measure length, diameter (distance considered starting in the abscission line in the middle of the fruit) and thickness of galled and healthy fruits. Aditionally, in transversal sections of galled fruits we measured parenchymatous tissue, and larval chamber size. In healthy and galled fruits, we quantified the water and biomass content by recording the fresh weight (FW), and then these were oven-dried for 36 hours at 70 °C. Later, the dry weight (DW) was quantified using a weighing scale (CP-225D, Sartorius, Germany, 0.01 g of accuracy). The water content was calculated as (FW-DW)/FW. The biomass content was defined as DW/FW. The water and biomass contents are expressed as a percentage.

In 3 individuals of P. praecox, 5 galled fruits (n = 15) and 5 healthy fruits (n = 15) were used to determine trichomes, stomatal, and pavement cell density, as well as stomata and pavement cell size. We applied a thin layer of clear nail varnish on the surface of the galled and healthy fruits in order to obtain permanent impressions of trichomes, stomata, and pavement cells. The area covered by the varnish layer was approximately 1 cm2. We determined the area of the 150 stomata and 150 pavement cells by measuring microphotographs of the samples with the software ImageJ (Rasband, 2017). The trichomes, stomatal, and pavement cell density were calculated in 2.7 mm2 in 3 randomly selected visual fields of an optical microscope per varnish layer (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, N.Y.).

Measurements of gs were determined in galled and healthy fruits in field using a porometer (SC-1, Decagon Devices Inc., Washington, USA). The sensor head of the porometer was situated in the middle section of the samples. Galled and healthy fruits were carefully placed on the sensor head without pressing, to avoid an overestimation of the gs. Seven measurement periods of gs were made between 07:00 h and 21:00 h on 3 different pairs of galled (n = 21) and healthy fruits (n = 21); 1 pair per individual of P. praecox.

Generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) were used to evaluate the relationship between galled and healthy fruits in each of the morphological traits (length, diameter, thickness, water content, biomass content) and anatomical features (trichomes, stomata, pavement cells). As fixed effects, we entered the galled and healthy fruits into the model. As random effect, we used intercepts for individuals of P. praecox, as well as random slopes for the effect of galled and healthy fruits.

A GLMM was used to assess the effects of the time of the day, galled and healthy fruits on the gs. The fixed effects were the galled fruits, healthy fruits and the time of the day (07:00 to 21:00 h), while the random effects were the individuals of P. praecox, as well as random slopes for the effect of galled and healthy fruits. We assumed a gamma distribution for the model.

Visual inspection of residual plots indicates there was no deviation of homoscedasticity or normality. P-values were obtained by a likelihood ratio test of the full model with the effect against the model without the effect (Zuur et al., 2009). All statistical analyses were performed in R version 3.2.2 (R Development Core Team, 2017) with the package lme4 (Bates et al., 2015) and multicomp (Hothorn et al., 2008). For all statistical analyses, we reported the mean ± SE and the differences in magnitude (i.e., mm2, %, and density) between galled and healthy fruits, referred as estimated values calculated in the GLMMs.

Results

Twenty percent of the P. praecox fruits had galls, although some affected fruits had a few seeds in the apical portion of the fruit. The branches with only healthy fruits had on average 28.1 ± 1.38 fruits per branch (n = 299), while branches with galled fruits had 21.5 ± 2.04 fruits (fruits ± SE) per branch (n = 138). Galled fruits had a spherical shape and were green-reddish. Each galled fruit was composed of parenchymatous tissue with 0.4 ± 0.06 cm (cm ± SE) of thickness. This tissue surrounds a larval chamber, which was 0.1 ± 0.01 cm of diameter that holds only 1 galling insect larva.

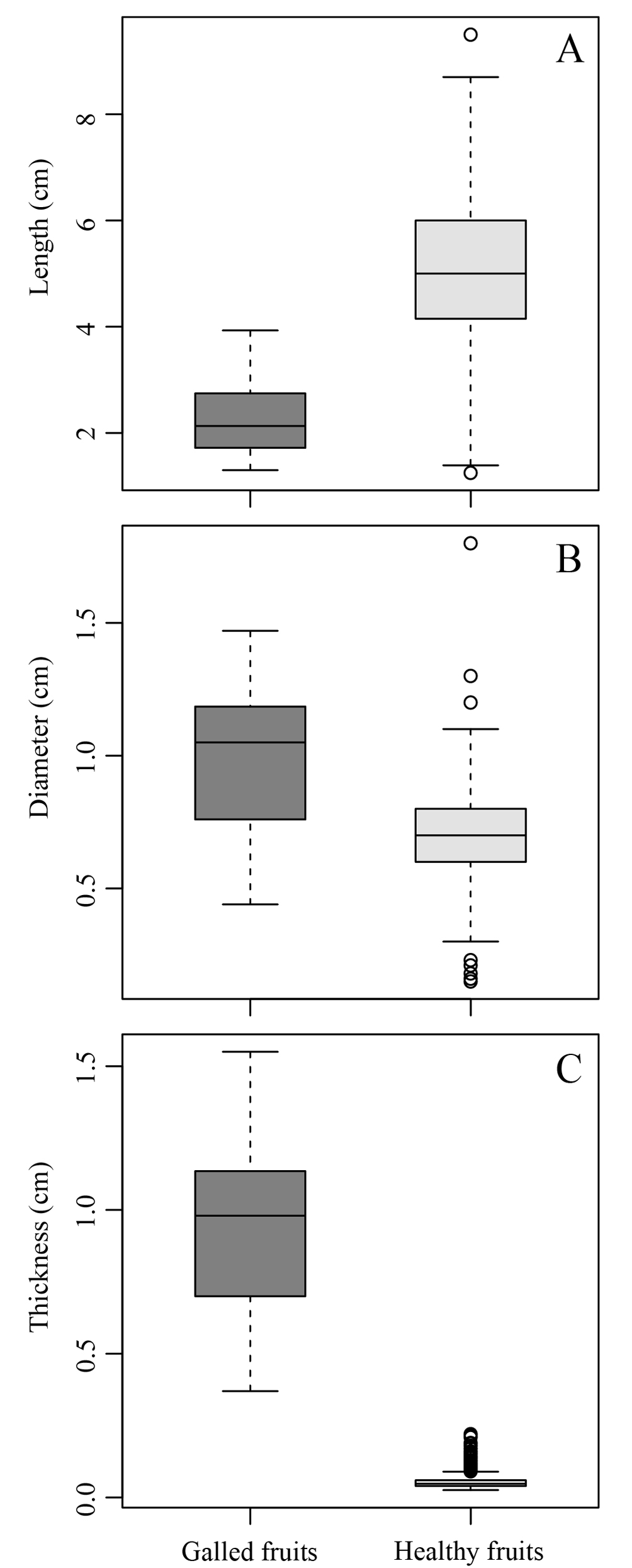

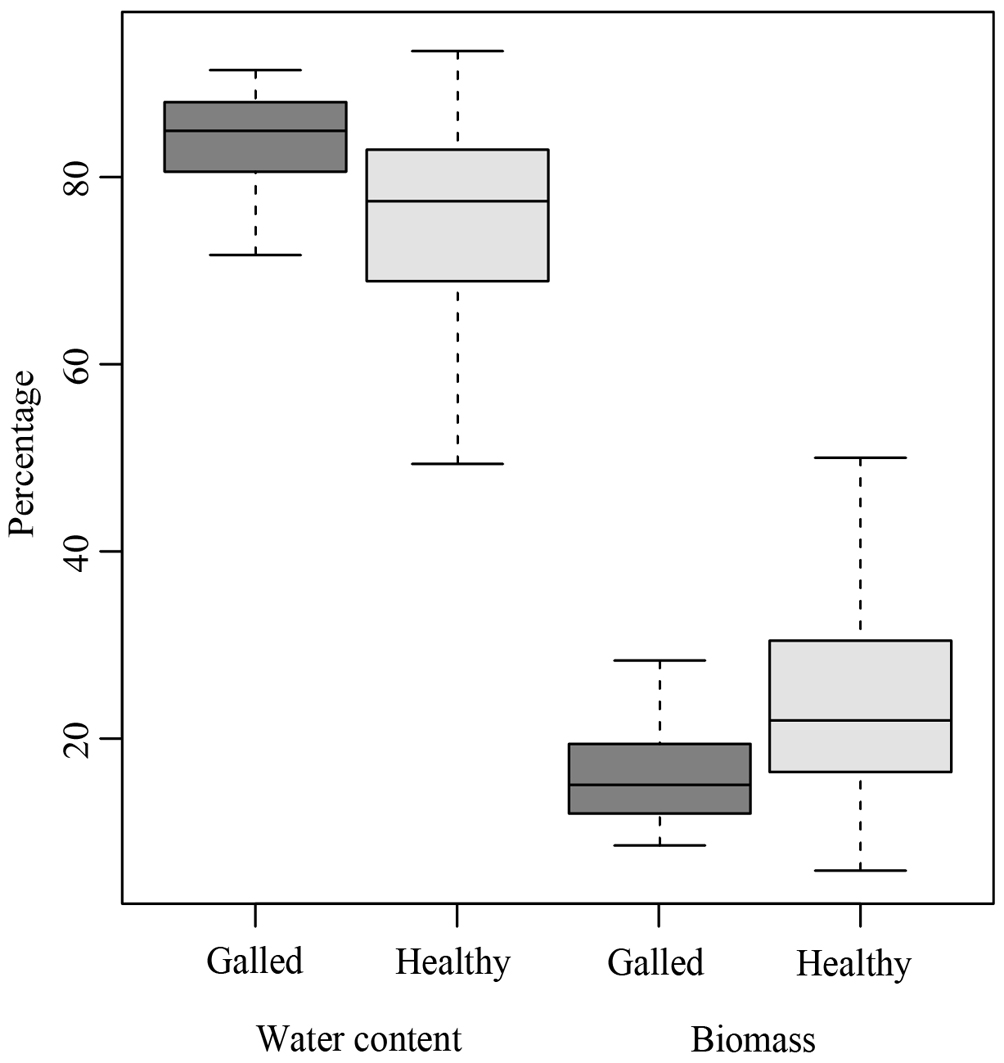

The morphological traits of galled and healthy fruits (length, diameter, thickness, water content, and biomass content) exhibited significant differences. The galled fruits were 2.91 ± 0.17 cm shorter than the healthy fruits (χ2 = 51.8, p < 0.001; Fig. 2A). On the other hand, galled fruits had 0.28 ± 0.04 cm larger diameter (χ2 = 23.2, p < 0.001; Fig. 2B) and were 0.87 ± 0.03 cm thicker (χ2 = 53.1, p < 0.001; Fig. 2C) than the healthy fruits. The water content was 4.24 ± 1.2% higher in the galled fruits (χ2 = 7.1, p < 0.01; Fig. 3), while healthy fruits had 4.2 ± 1.3% higher biomass content (χ2 = 7.16, p < 0.01; Fig. 3).

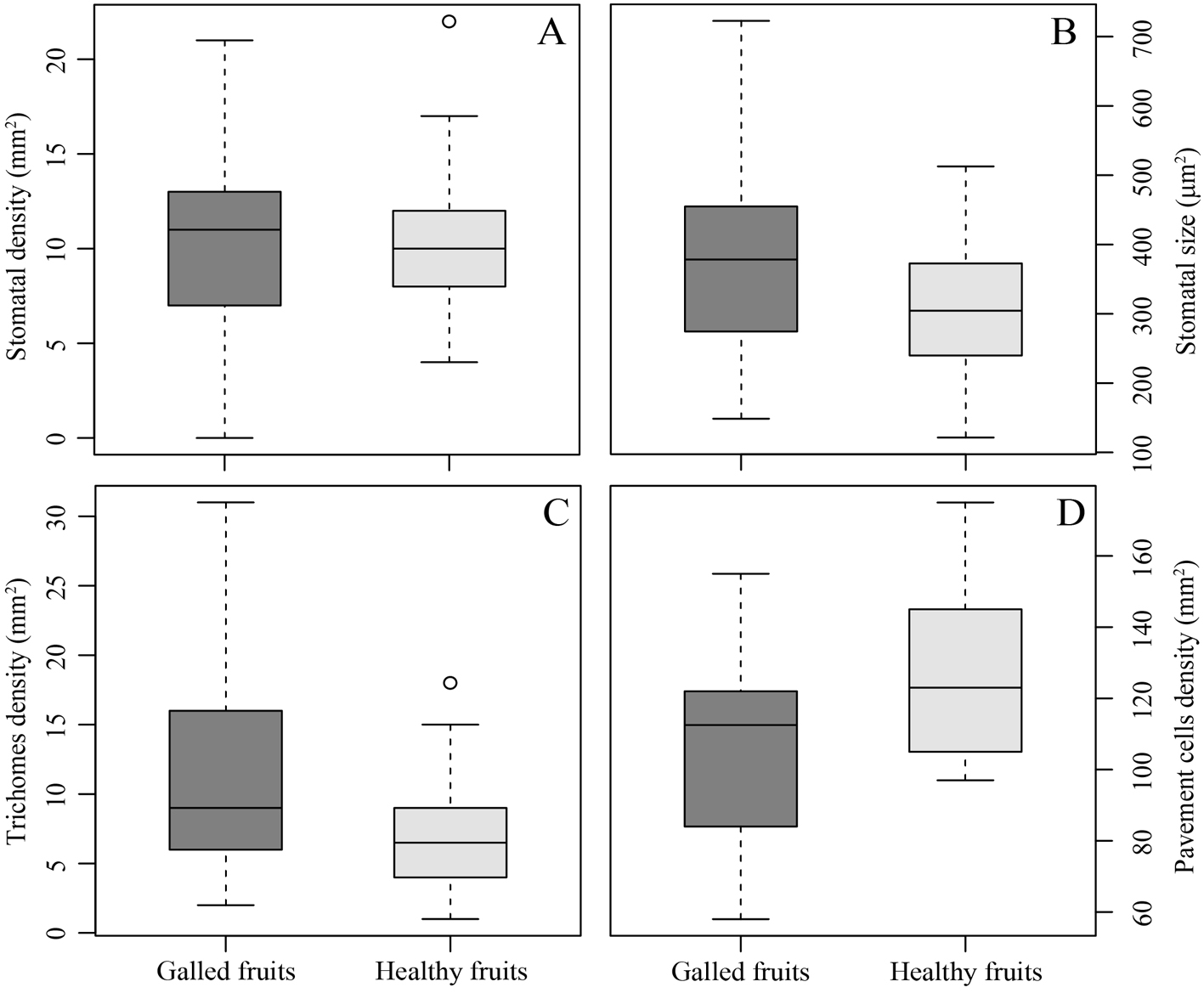

The stomatal density (0.28 ± 0.81 stomata mm2, χ2 = 0.12, p = 0.72; Fig. 4A) did not differ between galled and healthy fruits. Contrarily, trichome density (4.76 ± 1.42 trichomes mm2, χ2 = 7.43, p = 0.006; Fig. 4C) and pavement cell density (19.4 ± 8.19 pavement cells mm2, χ2 = 4.34, p < 0.05; Fig. 4D) were statistically different between galled and healthy fruits. The area of pavement cells did not differ between galled and healthy fruits (0.005 ± 0.005 µm2, χ2 = 0.77, p = 0.37), while the stomatal size was 70.13 ± 21.51 µm2 larger in galled fruits than in healthy fruits (χ2 = 5.05, p < 0.05; Fig. 4B).

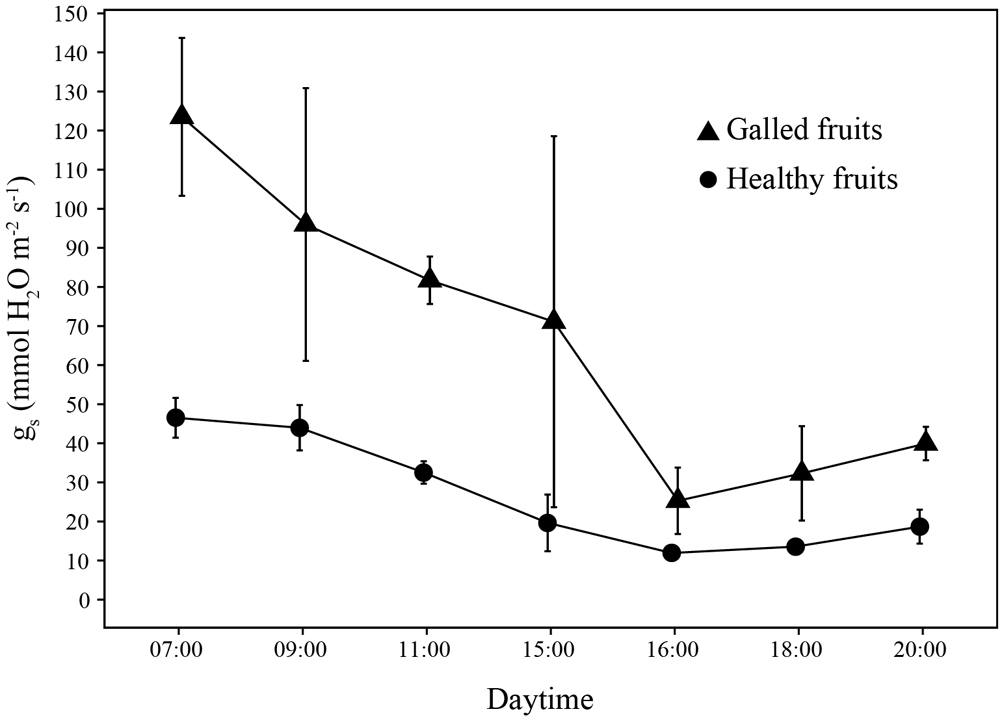

The gs was higher in galled fruits than in healthy fruits (χ2 = 12.6, p = 0.001). The interaction of daytime and the gall presence had a negative effect on the gs of galled fruits (χ2 = 36, p < 0.001). In the galled fruits, the highest values of gs were recorded at 07:00 h, while the lowest values were found in healthy fruits at 16:00 hrs. Likewise, the gs exhibited differences during the daytime (χ2 = 30, p < 0.001). Values of gs in galled and healthy fruits decreased throughout the day, with a slight increase in the last 2 records at night (18:00 to 20:00 h) (Fig. 5).

Discussion

In this study, we showed the incidence of galls in P. praceox fruits and its consequences on morphology and physiology. This is the first report of gall incidence on fruits in this semi-arid region of Central Mexico. In general, studies on galled fruits are scarce in the literature. We reviewed studies that report the presence of galls on reproductive structures, and we found 128 host plant species; Fabaceae was the most abundant host family (78 species), followed by Asteraceae (9 species), Boraginaceae (6) and Rubiaceae (6). The 2 most representative genera were Acacia (58 species) and Prosopis (14 species). Of the total number of host plant species found in our revision, 85.15% had galls on flowers (achene, buds, capitula, flowers, inflorescences) and the remaining 14.84% on fruits and seeds (Appendix).

Some species in South America have been reported as hosts of fruit-gall inducing insects, such as Conostegia xalapensis (Melastomataceae) (Chavarría et al., 2009); and Miconia calvescens (Melastomataceae) (Badenes-Perez & Johnson, 2007). Curiously, most studies are developed in the Costa Rican tropical dry forest (Janzen, 1982); Australian seasonally tropical forest (Kolesik et al., 2010), and Brazilian savanna (Santos et al., 2016). There are few studies on xeric environments that report the presence of galls on fruits, i.e. in Brazilian Restinga, Pithecellobium tortum have galls in seeds (de Macêdo & Monteiro, 1989). In our work we reported galls on P. praecox fruits and this is a pioneer study related to the study of galls in this area (Tehuacán-Cuicatlán, Mexico).

The galling insect Asphondylia sp. modifies the natural development of P. praecox fruits and negatively affects the fruit set of the host plant. In our bibliographical revision we found that the most representative taxonomic level of gall-forming insects on reproductive structures corresponded to the order Diptera (92.96%; 119 species) followed by Hymenoptera (6.25%; 8 species). The most important families of dipteran galling insects were Cecydomiidae (89.06%; 114 spp.) and Teprhitidae (3.9%, 5 spp.); of Coleoptera was Curculionidae (0.78%; 1 spp.); of Hymenoptera were Braconiidae (3.12%; 4 spp.), Agaonidae (0.78%; 1 spp.), Pteromalidae (0.78%; 1 spp.), Chalcidoidea (0.78%; 1 spp.) and Euritomidae (0.78%; 1 spp.). The most representative genus of galling insects was Asphondylia (44.87%; 60 spp.); followed by Dasineura (23.43%; 30 spp.), Allorhgas (3.12%; 4 spp.), Clinodiplosis (3.12%; 4 spp.), Urophora (3.12%; 4 spp.), Bruggmanniella (2.34%; 3 spp.), Eschizomia (1.56%; 2 spp.), and 13 genera correspond to 10.93%, each one represented by 1 species (Appendix).

Branches of P. praecox had 20% of gall incidence, indicating a high impact on fruit production. In association with pre-dispersal seed predation by coleopterans (Contreras-Varela, pers. obs.) and seed viability (Flores & Briones, 2001) the performance of P. praecox should be largely reduced.

Gall induction on P. praecox fruits should start inside the ovary where the cells are not yet differenciated, consequently the normal structure of the fruit is modified thus producing galls of spherical shape mainly without seeds (Fig. 1C). In general, galling insects require totipotent and undifferentiated tissues to induce galls development (Fernandes & Carneiro, 2009; Fernandes & Santos, 2014).

Galled fruits on P. praecox are mainly composed of parenchymatous tissue surrounding the larval chamber. We found that the biomass was greater in healthy fruits than in galled fruits. The water content in galled fruits (ca. 84.16%) suggests that galls are indeed important adaptations to live under harsh environments (Fernandes & Price, 1988; Price et al., 1987). The volumetric growth of fleshy fruits is the result of water and solutes accumulation that involves differences in water potential between the pedicel of the fruit and the rest of the plant (Matthews & Shackel, 2005). The gall formation in P. praecox involves the differentiation of a wide range of tissues that make the fleshy galls to superimpose an overall size. The water storage of galled fruits should be associated to solutes accumulation and to the increase of parenchyma cells turgor, these 2 conditions induce the cell hypertrophy and hyperplasia (Cosgrove, 2000). The parenchyma plays an important role for water and nutrient storage (Evert, 2006). To our knowledge, there is no information about the role of solutes content on the water movement to galls or if the chemical signals from the galling insects regulate the accumulation of solutes in galls. It has been reported that gall formation in vegetative structures comprise mainly the cellular elongation, however, cellular division and elongation has been associated to galls formation in reproductive structures (dos Santos et al., 2014). The sclerified tissue in galls and the high trichome density provide mechanical protection, the parenchymatous layer serves as a water and nutrient reservoir (Oliveira et al., 2014, 2016; Stone & Schönrogge, 2003).

The density of trichomes found on galled fruits of P. praecox was 1.5 times higher than on healthy fruits. In xeric environments, an increase of leaf pubescence leads to reduced water vapor transpiration and increases the thickness of the boundary layer (Evert, 2006; Pallardy, 2008). It has been reported that the pubescence of fruits significantly reduces water loss (Fernández et al., 2011). In P. praecox galled fruits, the high density of trichomes could prevent excessive moisture loss in the larval chamber and may maintain the internal temperature (Oliveira et al., 2014; Price et al., 1987). In addition, an elevated density of trichomes could reduce the vulnerability of the galling insects to potential natural enemies (Fernandes et al., 1987; Stone & Schönrogge, 2003; Woodman & Fernandes, 1991).

Galling insects do not only affect plant architecture and host organ morphogenesis, but also can modify physiological conditions such as stomatal conductance (Fay et al., 1996; Florentine et al., 2005; Larson, 1998), transpiration and CO2 assimilation (Dorchin et al., 2006). Those modifications influence positively to the gall (Fay et al., 1996) or negatively to the host (Florentine et al., 2005; Larson, 1998). Galled fruits of P. praecox increase the gs and stomatal size but had lower density of pavement cells in relation to healthy fruits; thus, it is possible that the increase in trichome density is the result of a compensatory mechanism to the high gas exchange of the galls with the environment; otherwise, the gs could be even higher (Fernández et al., 2011). Stomatal conductance estimates the rate of gases exchange through the stomata; it involves the density and aperture of stomata (Pietragalla & Pask, 2012) to infer transpiration and photosynthesis (Hiyama et al., 2005). According to Lemos-Filho and Isaias (2004), the fruits of Dalbergia miscolombium (Fabaceae) have a photosynthetic activity that contributes to the carbohydrates required for the fruit development. The gs in both galled and healthy fruits of P. praecox exhibited a similar pattern throughout the day, the higher values were recorded after the sunrise, indicating that the variation in gs of galls is due to water conditions in stem. The stomatal opening regulates the transpiration and prevents excessive water loss in the environment (Farquhar & Sharkey, 1982).

The gs in galled fruits was 2.5 times higher than in healthy fruits. Stomatal conductance can vary due to environmental (e.g., light intensity, CO2 concentration, relative humidity, temperature, wind, atmospheric pressure), anatomical (e.g., foliar area, pubescence, size and stomatal density), and/or endogenous factors (e.g., phytohormones) (Farquhar & Sharkey, 1982; Pallardy, 2008). In our study, the environmental conditions were similar in galled and healthy fruits. We found that galled fruits increased significantly the gs rates, although the stomatal density was not statistically different. This could be influenced by the production of signaling molecules, like phytohormones that promote the stomata opening and water movement to galls, in order to favor the water and nutrient continuum from host plant to gall. A revision of the abscisic acid (ABA) role in gall formation made by Tooker and Helms (2014) indicates that this phytohormone promotes gall growth. Even though the exact function of this hormone has not been yet fully recognized in gall tissues, ABA has been acknowledged as an endogenous regulator of the transpiration rate that controls the stomatal closing (Xiong & Zhu, 2003). We also suggest that similar endogenous regulation may occur on P. praecox galled fruits, but further phytochemical analysis will be necessary to determine the presence of ABA.

In conclusion, we found an important incidence of galled fruits on P. praecox that negatively affect morphological features of the fruits, with consequences on performance of the fruits. In addition, galled fruits are water sinks for this host plant that inhabits xeric environments. Future research is required to evaluate if the incidence of galled fruits negatively affects the plant fitness at the population level, in the different environmental conditions that occur in the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Biosphere Reserve.

Acknowledgements

To Facultad de Biología of the Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla and to the students, for their time and assistance during field work. Special thanks to Dr. Vicente Hernández (Red de Interacciones Multitróficas, INECOL) for his assistance in the identification of the galling insect. To the “Comisariado de Bienes Comunales” of Zapotitlán Salinas for leting us to work within the Botanical Garden “Helia Bravo Hollis” borders. To the Instituto de Ecología, A.C., for the research funds to A.A. (PO-20030-11315). GWF thanks the support of CNPq and FAPEMIG. Finally, thanks to Biól. Rosamond Coates (IB-UNAM) for her English revision. Suggestions of two anonymous reviewers improved the manuscript.

Appendix. Studies related to galls incidence in reproductive structures in plants, highlighting several aspects to the host plants, morphological traits of galls, as well as data of galling insects.

|

Appendix. Continued |

|||||||

|

Host |

Galls |

||||||

|

Family plant |

Species |

Organ |

Shape |

Color |

Galling insect |

Order/family |

Reference |

|

Host |

Galls |

||||||

|

Family plant |

Species |

Organ |

Shape |

Color |

Galling insect |

Order/family |

Reference |

|

Anacardiaceae |

Mangifera indica |

Flower |

Elliptical |

unknown |

Procontarina mangiferae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Tavares, 1917; Gagné, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Apocynaceae |

Peplonia asteria |

Flower |

Ovoid |

Green |

Asphondylia peplonidae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Gagné, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Apocynaceae |

Oxypetalum banksii |

Flower bud |

– |

– |

Asphondylia peploniae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Gagné, 2004; Flor & Maia, 2017 |

|

Arecaceae |

Geonoma cuneata |

Inflorescence |

Cylindrical |

Green-reddish |

Contarinia geonomae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Gagné et al., 2018 |

|

Asteraceae |

Porophyllum sp. |

Stem/flower |

Elliptical |

Purple |

Zalepidota ituensis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Tavares, 1917; Gagné, 1994, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Asteraceae |

Chromolaena odorata |

Achene |

Swollen |

unknown |

Asphondylia corbulae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Möhn, 1959; Gagné, 1994, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Asteraceae |

Fleischmannia microstemon |

Achene |

Swollen |

unknown |

Asphondylia corbulae. |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Möhn, 1959; Gagné, 1994, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Asteraceae |

Chromolaena odorata |

Bud |

Swollen |

unknown |

Perasphondylia reticulata |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Möhn, 1959; Gagné, 1977; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Asteraceae |

Sonchus arvensis |

Flower heads |

– |

– |

Tephritis dilacerata |

Diptera-Tephritidae |

Harris & Shorthouse, 1996 |

|

Asteraceae |

Centaurea maculosa |

Floral receptacule |

– |

– |

Urophora affinis |

Diptera-Tephritidae |

Crowe & Bourchier, 2006 |

|

Asteraceae |

Carduus nutans |

Flower heads |

– |

– |

Urophora solstitialis |

Diptera-Tephritidae |

Groenteman et al., 2007 |

|

Asteraceae |

Centaurea stoebe subsp. micranthos |

Flower heads |

– |

– |

Urophora quadrifasciata |

Diptera-Tephritidae |

Duguma et al., 2009 |

|

Asteraceae |

Centaurea solstitialis |

Flower heads |

– |

– |

Urophora sirunaseva |

Diptera-Tephritidae |

Woods et al., 2008 |

|

Boraginaceae |

Cordia alba |

Flower |

Swollen |

unknown |

Asphondylia cordiae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Gagné, 1994, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Boraginaceae |

Cordia dentata |

Flower |

Swollen |

unknown |

Asphondylia cordiae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Gagné, 1994, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Boraginaceae |

Cordia verbenacea |

Flower |

Ovoid |

Green |

Asphondylia cordiae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Maia, 2001; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Boraginaceae |

Tournefortia angustifolia |

Fruit |

Elongated sheroid |

unknown |

Asphondylia tournefortiae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Houard, 1933; Möhn, 1960; Gagné 1994, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Boraginaceae |

Tournefortia volubilis |

Fruit |

Elongated sheroid |

unknown |

Asphondylia tournefortiae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Houard, 1933; Möhn, 1960; Gagné 1994, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Boraginaceae |

Varronia curassavica |

Inflorescence |

Ovoid, hairy |

Green-yellow |

Asphondylia cfr. cordia |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Gagné, 1994; Maia et al., 2008; Flor & Maia, 2017 |

|

Brassicaceae |

Cakile maritima |

Bud |

Brown |

Gephyraulus zewaili |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Elsayed et al., 2017 |

|

|

Calophyllaceae |

Kielmeyera coriaceae |

Flower bud |

Swollen |

unknown |

Arcivena kielmeyera |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Gagné, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Calophyllaceae |

Kielmeyera rosea |

Flower bud |

Swollen |

unknown |

Arcivena kielmeyera |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Gagné, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Calophyllaceae |

Kielmeyera petiolaris |

Flower bud |

Swollen |

unknown |

Arcivena kielmeyera |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Gagné, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Calophyllaceae |

Kielmeyera variata |

Flower bud |

Swollen |

unknown |

Arcivena kielmeyera |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Gagné, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Calophyllaceae |

Kielmeyera speciosa |

Flower bud |

Swollen |

unknown |

Arcivena kielmeyera |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Gagné, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Calophyllaceae |

Kielmeyera rubiflora |

Flower bud |

Swollen |

unknown |

Arcivena kielmeyera |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Gagné, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Calophyllaceae |

Kielmeyera corymbosa |

Flower bud |

Swollen |

unknown |

Arcivena kielmeyera |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Gagné, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Celastraceae |

Maytenus obtusifolia var. obovata |

Fruit |

Ovoid |

Red |

Bruggmanniella maytenuse |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Maia, 2001; Gagné, 1994, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Convolvulaceae |

Jacquemontia holosericea |

Flower |

Ovoid |

Green/reddish |

Schizomyia santosi |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Maia, 2001; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Erythroxilaceae |

Erythroxylum ovalifolium |

Flower |

Ovoid |

Greenish |

Asphondylia sp. |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Maia, 2001; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Fabaceae |

Senna bicapsularis |

Flower |

Spherical |

Yellow |

Asphondylia sennae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Maia et al., 1992; Gagné, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Fabaceae |

Mimosa caesalpinifolia |

Fruit |

Unknown |

unknown |

Tavaresomyia mimosae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Möhn, 1961; Gagné, 1994, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Fabaceae |

Inga vera |

Seeds |

– |

– |

Allorhogas sp. |

Hymenoptera-Braconidae |

Morales-Silva & Modesto-Zampiero, 2018 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia longifolia |

Inflorescence |

– |

– |

Trichilogaster acaciaelongifoliae |

Hymenoptera-Pteromalidae |

Dennill, 1988 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia aneura |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura glauca |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia baileyana |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura pilífera |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia baileyana |

Flower buds |

– |

– |

Asphondylia pilogerminis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia cyclops |

Flower buds, fruit |

– |

– |

Asphondylia acaciae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia cyclops |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura dielsi |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia dealbata |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura pilífera |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia dealbata |

Flower buds |

– |

– |

Asphondylia pilogerminis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia deanei |

Flower buds |

– |

– |

Asphondylia glabrigerminis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia deanei |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura glomerata |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia deanei |

Fruit |

– |

– |

Asphondylia bursicola |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia decurrens |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura pilífera |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia decurrens |

Fruit |

– |

– |

Asphondylia bursicola |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia divergens |

Flower buds |

– |

– |

Asphondylia germinis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia elata |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura glomerata |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia floribunda |

Flower buds, fruit |

– |

– |

Asphondylia acaciae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia genistifolia |

Flower buds |

– |

– |

Asphondylia germinis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia hakeoides |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura glomerata |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia implexa |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura acaciaelongifoliae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia irrorata |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura fistulosa |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia irrorata |

Fruit |

– |

– |

Asphondylia bursicola |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia irrorata |

Flower buds |

– |

– |

Asphondylia pilogerminis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia littorea |

Flower buds |

– |

– |

Asphondylia germinis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia littorea |

Fruit |

– |

– |

Asphondylia occidentalis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia longifola |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura acaciaelongifoliae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia mearnsii |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura fistulosa |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia mearnsii |

Flower buds |

– |

– |

Asphondylia glabrigerminis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia mearnsii |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura glomerata |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia mearnsii |

Fruit |

– |

– |

Asphondylia bursicola |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia mearnsii |

Flower buds |

– |

– |

Asphondylia pilogerminis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia mearnsii |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura rubiformis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia maidenii |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura acaciaelongifoliae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia melanoxylon |

Flower buds, fruit |

– |

– |

Asphondylia acaciae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia melanoxylon |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura furcata |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia melanoxylon |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura glomerata |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia oldfieldii |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura oldfieldii |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia omalophylla |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura glauca |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia oshanesii |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura oshanesii |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia paradoxa |

Flower buds, fruit |

– |

– |

Asphondylia acaciae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia pendula |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura glauca |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia pentadenia |

Fruit |

– |

– |

Asphondylia occidentalis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia pycnantha |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura glomerata |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia ramulosa |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura glauca |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia ramulosa |

Fruit |

– |

– |

Asphondylia occidentalis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia retinoides |

Flower buds, fruit |

– |

– |

Asphondylia acaciae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia retinoides |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura glomerata |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia rostellifera |

Fruit |

– |

– |

Asphondylia occidentalis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia saligna |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura sulcata |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia schinoides |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura glomerata |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia longifolia subsp. sophorae |

Flower buds, fruit |

– |

– |

Asphondylia acaciae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia longifolia subsp. sophorae |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura acaciaelongifoliae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia sophorae x oxycedrus |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura acaciaelongifoliae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia stricta |

Open flowers |

– |

– |

Dasineura acaciaelongifoliae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia ulicifolia |

Flower buds, fruit |

– |

– |

Asphondylia acaciae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia urophylla |

Flower buds |

– |

– |

Asphondylia germinis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia verticillata |

flower buds, fruit |

– |

– |

Asphondylia acaciae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia xanthina |

Flower buds |

– |

– |

Asphondylia germinis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Kolesik et al., 2010 |

|

Fabaceae |

Acacia cavenia |

Bud |

– |

– |

Chalcidoidea sp. |

Hymenoptera-Chalcidoidea |

Maia, 2012 |

|

Fabaceae |

Gourliea decorticans |

Bud and stem |

– |

– |

Proseurytoma gallarum |

Hymenoptera-Eurytomidae |

Maia, 2012 |

|

Fabaceae |

Inga laurina |

Fruit |

– |

– |

Allorhogas sp. |

Hymenoptera-Brachonidae |

Santos et al., 2016 |

|

Fabaceae |

Enterolobium cyclocarpum |

Fruit |

– |

– |

Asphondylia enterolobi |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Janzen, 1982 |

|

Fabaceae |

Prosopis alba |

Flower |

– |

– |

Asphondylia sp. nr. prosopidis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Mc Kay & Gandolfo, 2007 |

|

Fabaceae |

Prosopis caldenia |

Flower |

– |

– |

Asphondylia sp. nr. prosopidis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Mc Kay & Gandolfo, 2007 |

|

Fabaceae |

Prosopis chilensis |

Flower |

– |

– |

Asphondylia sp. nr. prosopidis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Mc Kay & Gandolfo, 2007 |

|

Fabaceae |

Prosopis flexuosa |

Flower |

– |

– |

Asphondylia sp. nr. prosopidis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Mc Kay & Gandolfo, 2007 |

|

Fabaceae |

Prosopis nigra |

Flower |

– |

– |

Asphondylia sp. nr. prosopidis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Mc Kay & Gandolfo, 2007 |

|

Fabaceae |

Prosopis kuntzei |

Flower |

– |

– |

Asphondylia sp. nr. prosopidis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Mc Kay & Gandolfo, 2007 |

|

Fabaceae |

Prosopis ruscifolia |

Flower |

– |

– |

Asphondylia sp. nr. prosopidis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Mc Kay & Gandolfo, 2007 |

|

Fabaceae |

Prosopis affinis |

Unriped pods |

– |

– |

Asphondylia sp. nr. prosopidis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Mc Kay & Gandolfo, 2007 |

|

Fabaceae |

Prosopis alba |

Unriped pods |

– |

– |

Asphondylia sp. nr. prosopidis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Mc Kay & Gandolfo, 2007 |

|

Fabaceae |

Prosopis caldenia |

Unriped pods |

– |

– |

Asphondylia sp. nr. prosopidis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Mc Kay & Gandolfo, 2007 |

|

Fabaceae |

Prosopis chilensis |

Unriped pods |

– |

– |

Asphondylia sp. nr. prosopidis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Mc Kay & Gandolfo, 2007 |

|

Fabaceae |

Prosopis flexuosa |

Unriped pods |

– |

– |

Asphondylia sp. nr. prosopidis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Mc Kay & Gandolfo, 2007 |

|

Fabaceae |

Prosopis kuntzei |

Unriped pods |

– |

– |

Asphondylia sp. nr. prosopidis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Mc Kay & Gandolfo, 2007 |

|

Fabaceae |

Prosopis nigra |

Unriped pods |

– |

– |

Asphondylia sp. nr. prosopidis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Mc Kay & Gandolfo, 2007 |

|

Lamiaceae |

Hyptis sp. |

Flower |

Spherical |

unknown |

Asphondylia canastrae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Gagné, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Loranthaceae |

Struthanthus sp. |

Fruit |

Globular |

unknown |

Asphondylia struthanthi |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Gagné, 1994, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Loranthaceae |

Psittacanthus robustus |

Flower |

Unknown |

unknown |

Schizomyia sp. |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Gagné, 1994; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Malpghiaceae |

Byrsonima sericea |

Inflorescence |

Ovoid |

Brown |

Bruggmanniella byrsonimae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Maia, 2001; Gagné 1994, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Malphigiaceae |

Byrsonima sericea |

Bud |

Cylindrical |

Green |

Bruggmanniella byrsonimae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Guimarães et al., 2014 |

|

Malpighiaceae |

Heteropteris sp. |

Flower |

Swelling |

Cantarinia sp. |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Gagné, 1994; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

|

Malpighiaceae |

Heteropterys nitida |

Flower |

Elliptical |

Yellow |

Clinodiplosis floricola |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Maia, 2001; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Malvaceae |

Waltheria indica |

Leaf/inflorescence |

Spherical |

yellow/brown |

Anisodiplosis praecox |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Maia & Fernandes, 2005; Almeida et al., 2006; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Melastomataceae |

Conostegia xalapensis |

Fruit |

– |

– |

Allorhogas conostegia |

Hymenoptera-Braconidae |

Chavarria et al., 2009 |

|

Melastomataceae |

Miconia calvescens |

Fruit |

– |

– |

Apion sp. |

Coleoptera-Curculionidae |

Badenes-Perez & Johnson, 2007 |

|

Melastomataceae |

Miconia calvescens |

Fruit |

– |

– |

Allorhogas sp. |

Hymenoptera-Braconidae |

Badenes-Perez & Johnson, 2007 |

|

Moraceae |

Chlorophora tinctoria |

Flower |

Swollen |

unknown |

Clinodiplosis chlorophorae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Rübsaamen, 1905; Gagné, 1994; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Moraceae |

Ficus sp. |

Flower |

– |

– |

Agaonidae sp. |

Hymenoptera-Aganoidae |

Maia, 2012 |

|

Myrtaceae |

Eugenia buxifolia |

Fruit |

Subglobular |

Green |

Dasineura eugeniae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Gagné, 1994, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Rubiaceae |

Undetermined |

Flower |

Subovoid |

Green |

Asphondylia bahiensis |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Houard, 1933; Gagné 1994, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Rubiaceae |

Undetermined |

Flower |

Subovoid/elliptical |

Green |

Asphondylia parva |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Gagné 1994, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Rubiaceae |

Diodia gymnocephala |

Flower |

Elliptical |

Green |

Clinodiplosis diodiae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Maia,2001; Gagné, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Rubiaceae |

Borreria sp. |

Flower |

Swollen |

unknown |

Asphondylia borreriae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Gagné, 1994, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Rubiaceae |

Diodia sp. |

Flower |

Swollen |

unknown |

Asphondylia borreriae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Gagné, 1994, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Rubiaceae |

Borreria verticillata |

Inflorescence |

Fusiform |

Green |

Asphondylia borreriae |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Maia et al., 1992; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

|

Solanaceae |

Solanum sp. |

Fruit |

Spherical |

Green |

Asphondylia fructicolo |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Flor & Maia, 2017 |

|

Verbenaceae |

Lantana sp. |

Flower |

Ovoid |

Pink |

Clinodiplosis pulchra |

Diptera-Cecidomyiidae |

Tavares, 1918; Houard, 1933; Gagné, 1994, 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009 |

References

Almeida, F. V. M., Santos, J. C., Silveira, F. A. O., & Fernandes, G. W. (2006). Distribution and frequency of galls induced by Anisodiplosis waltheriae Maia (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) on the invasive plant Waltheria indica L. (Sterculiaceae). Neotropical Entomology, 35, 435–439.

Araújo, W. S., Sobral, F. L., & Maracahipes, L. (2014). Insect galls of the Parque Nacional das Emas (Mineiros, GO, Brazil). Check List, 10, 1445–1451.

Arias, A. A., Valverde, M. T., & Reyes, J. (2001). Las plantas de la región de Zapotitlán de Salinas, Puebla. Mexico D.F.: Instituto Nacional de Ecología.

Badenes-Perez, F. R., & Johnson, M. T. (2007). Ecology and impact of Allorhogas sp. (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) and Apion sp. (Coleoptera: Curculionoidea) on fruits of Miconia calvescens DC (Melastomataceae) in Brazil. Biological Control, 43, 317–322.

Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67, 1–48.

Blanche, K. R. (2000). Diversity of insect-induced galls along a temperature -rainfall gradient in the tropical savannah region of the Northern Territory, Australia. Austral Ecology, 25, 311–318.

Blanche, K. R., & Ludwig, J. A. (2001). Species richness of gall-inducing insects and host plants along an altitudinal gradient in Big Bend National Park, Texas. The American Midland Naturalist Journal, 145, 219–232.

Blanche, K. R., & Westoby, M. (1995). Gall-forming insect diversity is linked to soil fertility via host plant taxon. Ecology, 76, 2334–2337.

Carneiro, M. A. A., Branco, C. S. A., Braga, C. E. D., Almada, E. D., Costa, M. B. M., Maia, V. C. et al. (2009). Are gall midge species (Diptera, Cecidomyiidae) host plant-specialists? Revista Brasileira de Entomologia, 53, 365–378.

Chavarría, L., Hanson, P., Marsh, P., & Shaw, S. (2009). A phytophagous branconid, Allorhogas conostegia sp. nov. (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), in the fruits of Conostegia xalapensis (Bonpl.) D. Don (Melastomataceae). Journal of Natural History, 43, 2667–2689.

Coelho, M. S., Almada, E., Fernandes, G. W., Carneiro, M. A. A., Santos, R. M., Quintino, A. V. et al. (2009). Gall inducing arthropods from a seasonally dry tropical forest in Serra do Cipó, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia, 53, 404–14.

Conagua (Comisión Nacional del Agua). (2010). Datos de precipitación y temperatura de estaciones meteorológicas. Sección Puebla, Puebla. Puebla: Conagua.

Cosgrove, D. J. (2000). Loosening of plant cell walls by expansins. Nature, 407, 321–326.

Crowe, M. L., & Bourchier, R. S. (2006). Interspecific interactions between the gall-fly Urophora affinis Frfld. (Diptera: Tephritidae) and the weevil Larinus minutus Gyll. (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), two biological control agents released against spotted knapweed, Centaurea stobe L. ssp. micranthos. Biocontrol Science and Technology, 16, 417–430.

Cuevas-Reyes, P., Quesada, M., Hanson, P., Dirzo, R., & Oyama, K. (2004). Diversity of gall-inducing insects in a Mexican tropical dry forest: the importance of plant species richness, life-forms host plant age and plant density. Journal of Ecology, 92, 707–716.

de Macêdo, M. V., & Monteiro, R. T. (1989). Seed predation by a braconid wasp, Allorhogas sp. (Hymenoptera). Journal of the New York Entomological Society, 97, 358–362.

Dennill, G. B. (1988). Why a gall former can be a good biocontrol agent: the gall wasp Trichilogaster acaciaelongifoliae and the weed Acacia longifolia. Ecological Entomology, 13, 1–9.

Dorchin, N., Cramer, M. D., & Hoffmann, J. H. (2006). Photosynthesis and sink activity of wasp-induced galls in Acacia pycnantha. Ecology, 87, 1781–1791.

dos Santos, I. R. M., de Oliveira, D. C., da Silva, C. R. G., & Kraus, J. E. (2014). Developmental anatomy of galls in the Neotropics: arthropods stimuli versus host plant constraints. In G. W. Fernandes, & C. J. Santos (Eds.), Neotropical insect galls (pp. 429–463). Dordrecht: Springer.

Duguma, D., Kring, T. J., & Wiedenmann, R. N. (2009). Seasonal dynamics of Urophora quadrifasciata on spotted knapweed in the Arkansas Ozarks. The Canadian Entomologist, 141, 70–79.

Elsayed, A. K., Karam, H. H., & Tokuda, M. (2017). A new Gephyraulus species (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) inducing flower bud galls on the European sea rocket Cakile maritima Scop. (Brassicaceae). Applied Entomology and Zoology, 52, 553–558.

Espírito-Santo, M. M., & Fernandes, G. W. (2007). How many species of gall-inducing insects are there on earth, and where are they? Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 100, 95–99.

Evert, R. F. (2006). Esau’s plant anatomy. Meristems, cells, and tissues of the plant body: their structure, function, and development. New Jersey: John Wiley, & Sons.

Farquhar, G. D., & Sharkey, T. D. (1982). Stomatal conductance and photosynthesis. Annual Review of Plant Physiology, 33, 317–345.

Fay, P. A., Harnett, D. C., & Knapp, A. K. (1993). Increased photosynthesis and water potentials in Silphium integrifolium galled by cynipid wasps. Oecología, 93, 114–120.

Fay, P. A., Hartnett, D. C., & Knapp, A. K. (1996). Plant tolerance of gall insect attack and gall-insect performance. Ecology, 77, 521–534.

Fernandes, G. W. (1987). Gall forming insects: their economic importance and control. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia, 31, 379–398.

Fernandes, G. W., Araújo, R. C., Araújo, S. C., Lombardi, J. A., Paula, A. S., Loyola Jr., R. et al. (1997). Insect galls from savanna and rocky fields of the Jequitinhonha Valley, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Naturalia, 22, 221–244.

Fernandes, G. W., & Carneiro, M. A. A. (2009). Insetos galhadores. In A. R. Panizzi, & J. R. P. Parra (Eds.), Bioecologia e nutrição de insetos: base para o manejo integrado de pragas (pp. 597–639). Brasilia: Embrapa Informação Tecnológica.

Fernandes, G. W., Martins, R. P., & Neto, T. (1987). Food web relationships involving Anadiplosis sp. galls (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) on Machaerium aculeatum (Leguminosae). Revista Brasileira de Botanica, 10, 117–123.

Fernandes, G. W., & Price, P. W. (1988). Biogeographical gradientes in galling species richness. Oecologia, 76, 161–167.

Fernandes, G. W., & Price, P. W. (1991). Comparison of tropical and temperate galling species richness: the roles of environmental harshness and plant nutrient status. In P. W. Price, T. M. Lewinsohn, G. W. Fernandes, & W. W. Benson (Eds.), Plant-animal interactions: evolutionary ecology in tropical and temperate regions (pp. 91–115). New Jersey: John Wiley, & Sons.

Fernandes, G. W., & Santos, J. C. (2014). Neotropical insect galls. New York: Springer.

Fernandes, G. W., Souza, A., & Sacchi, C. (1993). Impact of a Neolasioptera (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) stem galler on its host plant, Mirabilis linearis (Nyctaginaceae). Phytophaga, 5, 1–6.

Fernández, V., Khayet, M., Montero-Prado, P., Heredia-Guerrero, J. A., Liakopoulos, G., Karabourniotis, G. et al. (2011). New insights into the properties of pubescent surfaces: peach fruit as a model. Plant Physiology, 156, 2098–2108.

Florentine, S. K., Raman, A., & Dhileepan, K. (2005). Effects of gall induction by Epiblema strenuana on gas exchange, nutrients, and energetics in Parthenium hysterophorus. BioControl, 50, 787–801.

Flores, J., & Briones, O. (2001). Plant life-form and germination in a Mexican inter-tropical desert: effects of soil water potential and temperature. Journal of Arid Environments, 47, 485–497.

Gagné, R. J. (1977). The Cecidomyiidae (Diptera) associated with Chromolaena odorata (L.) K. and R. (Compositae) in the Neotropical Region. Brenesia, 12/13, 113–131.

Gagné, R. J. (1994). The gall midges of the Neotropical Region. New York: Cornell University Press.

Gagné, R. J. (2004). A catalog of the Cecidomyiidae (Diptera) of the world. Memoirs of the Entomological Society of Washington, 25, 1–408.

Gagné, R. J., Ley-López, J. M., & Hanson, P. E. (2018). First New World record of a gall midge from palms: a new species of Contarinia (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) from Geonoma cuneata in Costa Rica. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington, 120, 51–61.

Gonçalves-Alvim, S. J., & Fernandes, G. W. (2001). Comunidades de insetos galhadores (Insecta) em diferentes fisionomias do cerrado em Minas Gerais, Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia, 18, 289–305.

Guimarães, A. L. A., Cruz, S. M. S., & Vieira, A. C. M. (2014). Structure of floral galls of Byrsonima sericea (Malpighiaceae) induced by Bruggmanniella byrsonimae (Cecidomyiidae, Diptera) and their effects on host plants. Plant Biology, 16, 467–475.

Haiden, S., Hoffmann, J., & Cramer, M. (2012). Benefits of photosynthesis for insects in galls. Oecologia, 170, 987–997.

Harris, P., & Shorthouse, J. D. (1996). Effectiveness of gall inducers in weed biological control. The Canadian Entomologist, 128, 1021–1055.

Hiyama, T., Kochi, K., Kobayashi, N., & S. Sirisampan. (2005). Seasonal variation in stomatal conductance and physiological factors observed in a secondary warm-temperate forest. Ecological Restoration, 20, 333–346.

Hothorn, T., Bretz, F., & Westfall, P. (2008). Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biometrical Journal, 50, 346–363.

Houard, C. (1933). Les Zoocécidies des Plantes de l ́Amérique du Sud e de l ́Amérique Central. Paris: Hermann et Cie. 519.

Isaias, R. M. S., Carneiro, R. G. S., Santos, J. C., & Oliveira, D. C. (2014). Gall morphotypes in the Neotropics and the need to standardize them. In G. W. Fernandes, & C. J. Santos (Eds.), Neotropical insect galls (pp. 51–67). Dordrecht: Springer.

Janzen, D. H. (1982). Variation in average seed size and fruit seediness in a fruit crop of a Guanacaste tree (Leguminosae: Enterolobium cyclocarpum). American Journal of Botany, 69, 1169–1178.

Kolesik, P., Adair, R. J., & Eick, G. (2010). Six new species of Asphondylia (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) damaging flower buds and fruit of Australian Acacia (Mimosaceae). Systematic Entomology, 35, 250–267.

Kurzfeld-Zexer, L., Wool, D., & Inbar, M. (2010). Modification of tree architecture by a gall-forming aphid. Trees-Structure and Function, 24, 13–18.

Larson, K. C. (1998). The impact of two gall-forming arthropods on the photosynthetic rates of their hosts. Oecologia, 115, 161–166.

Lemos-Filho, J. P., & Isaias, R. M. S. (2004). Comparative stomatal conductance and chlorophyll a fluorescence in leaves vs. fruits of the Cerrado legume tree, Dalbergia miscolobium. Brazilian Journal of Plant Physiology, 16, 89–93.

López-Galindo, F., Munóz-Iniestra, D., Hernández-Moreno, M., Soler-Aburto, A., Castillo-López, M. C., & Hernández-Arzate, I. (2003). Análisis integral de la toposecuencia y su influencia en la distribución de la vegetación y la degradación del suelo en la subcuenca de Zapotitlán Salinas, Puebla. Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 56, 19–41.

Maia, V. C. (2001). The gall midges (Diptera, Cecidomyiidae) from three restingas of Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia, 8, 583–630.

Maia, V. C. (2012). Richness of hymenopterous galls from South America. Papéis Avulsos de Zoologia (São Paulo), 52, 423–429.

Maia, V. C., Couri, M. S., & Monteiro, R. F. (1992). Sobre seis espécies de Asphondylia Loew, 1850 do Brasil (Diptera, Cecidomyiidae). Revista Brasileira de Entomologia, 36, 653–661.

Maia, V. C., & Fernandes, G. W. (2005). Two new species of Asphondylinii (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) associated with Bahuinia brevipes (Fabaceae) in Brazil. Zootaxa, 1091, 27–40.

Maia, V. C., Silveira, F. A. O., Oliveira, L. A., & Xavier, M. F. (2008). Asphondylia gochnatiae, a new species of gall midge (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) associated with Gochnatia polymorpha (Less.) Cabrera (Asteraceae). Zootaxa, 1740, 53–58.

Mani, M. S. (1964). Ecology of plant galls. Dordrecht: Springer Science.

Matthews, M. A., & Shackel, K. A. (2005). Growth and water transport in fleshy fruit. En N. M. Holbrook, & M. A. Zwieniecki (Eds.), Vascular transport in plants (pp. 181–197). Burlington, California: Academic Press.

McCrea, K. D., Abrahamson, W. G., & Weis, A. E. (1985). Goldenrod ball gall effect on Solidago altissima: 14C translocation and growth. Ecology, 66, 1902–1907.

Mc Kay, F., & Gandolfo, D. (2007). Phytophagous insects associated with the reproductive structures of mesquite (Prosopis spp.) in Argentina and their potential as biocontrol agents in South Africa. African Entomology, 15, 121–131.

Medianero, E., Valderrama, A., & Barrios, H. (2003). Diversidad de insectos minadores de hojas y formadores de agallas en el dosel y sotobosque del bosque tropical. Acta Zoológica Mexicana, 89, 153–168.

Möhn, E. (1959). Gallmücken (Diptera, Cecidomyiidae) aus El Salvador. 1. Teil. Senckenbergiana Biologica, 40, 297–368.

Möhn, E. (1960). Gallmücken (Diptera, Cecidomyiidae) aus El Salvador. 2. Teil. Senckenbergiana Biologica, 41, 197–240.

Möhn, E. (1961). Neue Asphondyliidi-Gattungen (Diptera, Itonididae). Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde, 49, 1–14.

Montaña, C., & Valiente-Banuet, A. (1998). Floristic life-form diversity along an altitudinal gradient in an intertropical semiarid Mexican region. Southwest Naturalist, 43, 24–39.

Morales-Silva, T., & Modesto-Zampieron, S. L. (2018). Occurrence of Allorhogas sp. (Hymenoptera: Braconidae: Doryctinae) associated with galls on seeds of Inga vera (Fabaceae) in Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Biology, 78, 178–179.

Oliveira, D. C., Isaias, R. M. S., Fernandes, G. W., Ferreira, B. G., Carneiro, R. G. S., & Fuzaro, L. (2016). Manipulation of host plant cells and tissues by gall-inducing insects and adaptive strategies used by different feeding guilds. Journal of Insect Physiology, 84, 103–113.

Oliveira, D. C., Moreira A. S. F. P., & Isaias, R. M. S. (2014). Functional gradients in insect gall tissues: studies on Neotropical host plants. En G. W. Fernandes, & C. J. Santos (Eds.), Neotropical insect galls (pp. 51–67). Dordrecht: Springer.

Oyama, K., Pérez-Pérez, M., Cuevas-Reyes, P., & R. Luna-Reyes. (2003). Regional and local species richness of gall-forming insects in two tropical rain forest in México. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 19, 595–598.

Pallardy, S. G. (2008). Physiology of woody plants. Burlington, California: Academic Press.

Patankar, R., Thomas, S. C., & Smith, S. M. (2011). A gall-inducing arthropod drives declines in canopy tree photosynthesis. Oecologia, 167, 701–709.

Pavón, N. P., & Briones, O. (2001). Phenological patterns of nine perennial plants in an intertropical semi-arid Mexican scrub. Journal of Arid Environments, 49, 265–277.

Pennington, T. D., & Sarukhán, J. (2005). Árboles tropicales de México: manual para la identificación de las principales especies. México D.F.: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Pezzini, F., Ranieri, B. D., Brandao, D. O., Fernandes, G. W., Quesada, M., Espirito-Santo, M. M. et al. (2014). Changes in tree phenology along natural regeneration in a seasonally dry tropical forest. Plant Biosystematics, 148, 1–10.

Pietragalla, J., & Pask, A. (2012). Stomatal conductance. En A. Pask, J. Pietragalla, D. Mullan, & M. Reynolds (Eds.), Physiological breeding II: a field guide to wheat phenotyping (pp. 15–17). México D.F.: CIMMYT.

Price, P. W., Fernandes, G. W., Lara, A. C. F., Brawn, J., Barrios, H., Wright, M. G. et al. (1998). Global patterns in local number of insect galling species. Journal of Biogeography, 25, 581–91.

Price, P. W., Fernandes, G. W., & Waring, G. L. (1987). Adaptive Nature of insect galls. Environmental Entomology, 16, 15–24.

Quintero, C., Garibaldi, L. A., Grez, A., Polidori, C., & Nieves-Aldrey, J. L. (2014). Galls on the temperate forest of southern South America: Argentina and Chile. En G. W. Fernandes, & C. J. Santos (Eds.), Neotropical insect galls (pp. 429–463). Dordrecht: Springer.

R Development Core Team. (2017). R: a language and environment for statistical computing, version 3.3.0. Vienna, Austria. Retrieved on March 11th., 2017, from: https://www.r-project.org/

Raman, A. (2007). Insect-induced plant galls of India: unresolved questions. Current Science, 92, 748–757.

Rasband, W. S. (2017). ImageJ. National Institutes of Health, USA. Retrieved on March 11th., 2017, from: http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/

Rübsaamen, E. H. (1905). Beiträge zur Kenntnis aussereuropäischer Zoocecidien. II. Beitrag: Gallen aus Brasilien und Peru. Marcellia, 4, 65–85.

Rzedowski, J. (2006). Vegetación de México. México D.F.: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad.

Santos, J. C., De Araujo, N. A. V., Venancio, H., Andrade, J. F., Alves-Silva, E., Almeida, W. R. et al. (2016). How detrimental are seed galls to their hosts? Plant performance, germination, developmental instability and tolerance to herbivory in Inga laurina, a leguminous tree. Plant Biology, 18, 962–972.

Silva, I. M., Andrade, G. I., Fernandes, G. W., & Lemos-Filho, J. P. (1996). Parasitic relationships between a gall-forming insect Tomoplagia rudolphi (Diptera: Tephritidae) and its host plant (Vernonia polyanthes, Asteraceae). Annals of Botany, 78, 45–48.

Stone, G. N., & Schönrogge, K. (2003). The adaptive significance of insect gall morphology. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 18, 512–522.

Tavares, J. S. (1917). Cecidias brazileiras que se criam em plantas das Compositae Rubiaceae, Tiliaceae, Lythraceae e Artocarpaceae. Broteria: Série Zoológica, 15, 113–181.

Tavares, J. S. (1918). Cecidologia brazileira. Cecidias que se criam em plantas das famílias das Verbenaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Malvaceae, Anacardiaceae, Labiatae, Rosaceae, Anonaceae, Ampelidaceae, Bignoniaceae, Aristolochiaceae e Solanaceae. Brotéria: Série Zoológica, 16, 21–68.

Tooker, J. F., & Helms, A. M. (2014). Phytohormone dynamics associated with gall insects, and their potential role in the evolution of the gall-inducing habitat. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 40, 742–753.

Villaseñor, J. L. (2016). Checklist of the native vascular plants of Mexico. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 87, 559–902.

Woodman, R. L., & Fernandes, G. W. (1991). Differential mechanical defense: herbivory, evapotranspiration, and leaf-hairs. Oikos, 60, 11–19.

Woods, D. M., Pitcairn, M. J. Joley, D. B., & Turner, C. E. (2008). Seasonal phenology and impact of Urophora sirunaseva on yellow starthistle seed production in California. Biological Control, 47, 172–179.

Xiong, L., & Zhu, J. K. (2003). Regulation of abscisic acid biosynthesis. Plant Physiology, 133, 29–36.

Zavala, A. (1982). Estudios ecológicos en el Valle semiárido de Zapotitlán, Puebla I. Clasificación numérica de la vegetación basada en atributos binarios de presencia o ausencia de las especies. Biotica, 7, 99–120.

Zuur, A., Leno, E. N., Walker, N., Saveliev, A. A., & Smith, G. M. (2009). Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R. New York: Springer-Verlag.