Raciel Cruz-Elizalde *, Norma Hernández-Camacho, Rubén Pineda-López, Robert W. Jones

Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales, Laboratorio de Ecología y Diversidad Faunística, Avenida de las Ciencias s/n, Santa Fe Juriquilla, 76230 Querétaro, Querétaro, Mexico

*Corresponding author: cruzelizalde@gmail.com (R. Cruz-Elizalde)

Received: 30 September 2022; accepted: 9 June 2023

Abstract

The Sierra Gorda de Querétaro Biosphere Reserve (SGQBR) is one of the largest natural protected areas in Mexico; however, little is known about the richness and diversity of amphibians and reptiles. We present an updated list of species of both groups, the conservation status of these species, as well as an analysis of their diversity with respect to other protected natural areas (NPAs) in central Mexico. The SGQBR contains 132 herpetofauna species (35 amphibians and 97 reptiles). The richest and most diverse families for amphibians were Hylidae (anurans) and Plethodontidae (caudates), and for reptiles Phrynosomatidae (lizards), Colubridae and Dipsadidae (snakes). The values of taxonomic diversity of the SGQBR were similar to those for the regional pool considering others NPAs. However, it did not achieve the highest values compared to the adjacent Los Mármoles National Park or Sierra Gorda de Guanajuato Biosphere Reserve. There was a high complementarity in the species composition between El Chico National Park and SGQBR for both herpetofauna groups. Although a formal list is presented, it is necessary to carry out a greater number of studies focused on analyzing diversity, considering functional attributes of the species and the richness by vegetation types.

Keywords: Conservation; Diversity; Herpetofauna; IUCN; Semarnat

© 2023 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Anfibios y reptiles de la Reserva de la Biosfera Sierra Gorda de Querétaro, México: riqueza de especies, estado de conservación y comparación con otras áreas naturales protegidas del centro de México

Resumen

La Reserva de la Biosfera Sierra Gorda de Querétaro (RBSGQ) es una de las áreas naturales protegidas más grandes de México; sin embargo, poco se sabe sobre la riqueza y diversidad de anfibios y reptiles. Presentamos una lista actualizada de especies de ambos grupos, su estado de conservación y un análisis de su diversidad con respecto a otras áreas naturales protegidas (ANP) en el centro de México. La SGQBR contiene 132 especies de herpetofauna (35 anfibios y 97 reptiles). Las familias más ricas y diversas de anfibios fueron Hylidae (anuros) y Plethodontidae (caudados), y de reptiles Phrynosomatidae (lagartos), Colubridae y Dipsadidae (serpientes). Los valores de diversidad taxonómica de la SGQBR fueron similares a los del pool regional considerando otras ANP; sin embargo, no alcanzó los valores más altos en comparación con el Parque Nacional Los Mármoles adyacente o la Reserva de la Biosfera Sierra Gorda de Guanajuato. Hubo una alta complementariedad en la composición de especies entre el Parque Nacional El Chico y la RBSGQ para esta herpetofauna. Si bien se presenta un listado formal, es necesario un mayor número de estudios para analizar la diversidad, considerando atributos funcionales de las especies y la riqueza por tipos de vegetación.

Palabras clave: Conservación; Diversidad; Herpetofauna; UICN; Semarnat

© 2023 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. Este es un artículo Open Access bajo la licencia CC BY-NC-ND

Introduction

The loss of vegetation and environmental degradation, together with other anthropogenic impacts such as climate change and pollution, are the main causes of the loss of global biodiversity (Barragán et al., 2011; Cayuela et al., 2006). This loss of biodiversity has been greater in regions sharing both temperate and tropical environments, where there is a high number of species and levels of endemism (Fischer & Lindenmayer, 2007). Such is the case of the central region of Mexico (Flores-Villela et al., 2010; Ochoa-Ochoa et al., 2014). The great diversity of vertebrate groups in central Mexico is mainly due to the complex orography that gives rise to a high variation of vegetation types such as oak, pine, and cloud forests, and seasonally dry to wet tropical forests (Steinmann et al., 2021); all of which contain environments where high species richness has been recorded (Flores-Villela et al., 2010). In addition, distinct patterns of diversification and distribution have been generated in central Mexico within distinct groups of terrestrial vertebrates, exemplified by amphibians (García-Castillo et al., 2017), reptiles (Bryson et al., 2014), birds (Martínez-Morales, 2007) and mammals (Vázquez-Ponce et al., 2021).

Various studies indicate that landscape fragmentation, as well as changes in land use, are highly detrimental to certain groups of vertebrates such as amphibians and reptiles (Frías-Álvarez et al., 2010; Pineda et al., 2005; Suazo-Ortuño et al., 2015). These groups are highly dependent on habitat conditions such as humidity, precipitation, temperature and, in general, adequate environmental quality (Vitt & Caldwell, 2009). Given these habitat limitations, amphibians and reptiles are considered especially sensitive bioindicator groups of environmental health (García-Bañuelos et al., 2019; Nori et al., 2015). In this context, different strategies have been developed to establish conservation measures for these and other biological groups (Figueroa & Sánchez-Cordero, 2008; García-Bañuelos et al., 2019; Sánchez-Cordero et al., 2005), of which the creation of Natural Protected Areas (NPAs) is the main measure (Mittermeier et al., 1998; Rodrigues et al., 2004).

In Mexico, there are 203 NPAs classified in different categories such as national parks, biosphere reserves, natural monuments, sanctuaries, among others, and the Biosphere Reserve category holds the highest degree of importance (Conanp, 2023). Although the establishment of NPAs seeks the conservation of various elements of nature, including ecosystem services, the diversity of flora and fauna or the preservation of natural monuments, most NPAs have been established arbitrarily, generally because basic biological information of the species of various biological groups found in these areas is lacking (Ervin, 2003; García-Bañuelos et al., 2019). Within the Biosphere Reserves of central Mexico, a high diversity of amphibian and reptile species has been recorded. For example, the Barranca de Metztitlán Biosphere Reserve has 69 species (Valdez-Rentería et al., 2018), which is a high number compared to other areas such as Los Mármoles National Park with 36 species (Cruz-Elizalde et al., 2015), El Chico National Park with 22 (Cruz-Elizalde et al., 2015) or La Malinche National Park with 28 (Díaz de la Vega-Pérez et al., 2019). Also, other areas such as Valle de Tehuacán Cuicatlán in Puebla, Nevado de Toluca in Estado of México, or Mariposa Monarca Biosphere Reserve stand out for their territorial extension and richness of vertebrate species, mainly amphibians and reptiles (Conanp, 2023). Despite recent work focused on determining the biological richness in the NPAs of Mexico, and mainly in central Mexico (Cruz-Elizalde et al., 2015; Valdez-Rentería et al., 2018), a large number requires basic biodiversity research in NPAs of different categories, mainly Biosphere Reserves (Figueroa & Sánchez-Cordero, 2008; Flores-Villela et al., 2010). This is urgent because the central region of Mexico is where the highest human population growth has been reported, which, together with the transformation of areas of natural vegetation, puts the diversity of various biological groups at risk, especially amphibians and reptiles (Mercado & del Val, 2021; Ramírez-Bautista et al., 2020).

The Sierra Gorda de Querétaro Biosphere Reserve (SGQBR) is immersed in the limits of the Sierra Madre Oriental and the Mexican Plateau biogeographic provinces (Carabias-Lillo et al., 1999; Morrone, 2005). This NPA was decreed on 19 May 1997, and has an area of 383,567.45 ha (Conanp, 2023). The SGQB contains varied types of vegetation, such as xeric scrub, pine forest, oak, cloud forest and tropical forests (Carabias-Lillo et al., 1999; Zamudio et al., 1992). These diverse vegetation types are the product of the complex orography of the region, which has a varied topography ranging in elevations from 260 to 3,100 m asl, and wide-ranging levels of annual from 350 to 1,500 mm (Jones & Serrano-Cárdenas, 2018). However, as for almost all regions of Mexico, human settlements are found throughout the reserve with associated anthropic environments such as crop areas (temporary and irrigated), and pasture areas for cattle with various levels of management (Zamudio et al., 1992).

The mountainous ecosystems where SGQBR occurs stand out as areas of great richness and number of amphibian and reptile endemism (Flores-Villela et al., 2010), many of which are also categorized as endangered or critically endangered (Wilson, Johnson et al., 2013; Wilson, Mata-Silva et al., 2013). Accordingly, a high number of amphibian and reptile species are in high conservation categories both in national conservation lists such as NOM-059-SEMARNAT (Semarnat, 2010), and international species lists such as the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN, 2023). In addition, high values are given to these species in the Environmental Vulnerability Index within the metrics that also analyze ecological aspects of species (EVS; Wilson, Johnson et al., 2013; Wilson, Mata-Silva et al., 2013). These conservation agencies and their categories have recently been used in various studies at the state level (Lemos-Espinal & Smith, 2020; Ramírez-Bautista et al., 2020; Torres-Hernández et al., 2021), or for groups (García-Padilla et al., 2021), reflecting the need to include and analyze the conservation status of species at different spatial scales (Wilson et al., 2017).

According to the diversity of vertebrates reported for the SGQBR, there are several studies that report on the diversity of birds (Pineda-López et al., 2010), mammals (Anaya-Zamora et al., 2017; Agoitia-Fonseca, 2019) and fish (Gutiérrez-Yurrita & Morales-Ortiz, 2004). The richness and diversity of amphibians and reptiles in this region has not been adequately studied, since even though there are general lists of the herpetofauna of Querétaro (Dixon & Lemos-Espinal, 2010; Cruz-Elizalde et al., 2016, 2019; Cruz-Elizalde, Pineda-López et al., 2022; Cruz-Elizalde, Ramírez-Bautista et al., 2022; Tepos-Ramírez et al., 2023), as well as isolated records in this area (Tepos-Ramírez, Flores-Villela et al., 2021; Tepos-Ramírez, Pineda-López et al., 2021, 2022), there is no complete or updated list of the herpetofauna of this area with the only formal work available for the SGQBR is that of Gillingwater and Patrikeev (2004), where they report a total of 23 species (10 amphibians and 13 reptiles).

Despite that SGQBR is a large area that contains diverse environments, published estimates of amphibians and reptiles (highly species-rich groups) are surprisingly low. This highlights the need for a more thorough and formal list of species, including an analysis of their diversity and their conservation status. Thus, the general objective of this study was to determine the richness of amphibian and reptile species in the SGQBR, which since the work of Gillingwater and Patrikeev (2004), to date does not have an updated herpetofauna formal list, nor an analysis of the species´ conservation status. The specific objectives of this study were i) to determine the richness of amphibians and reptiles in the reserve, ii) to compare the taxonomic diversity of the herpetofauna with other NPAs in central Mexico, iii) to analyze the degree of similarity in the composition of species between NPAs, and iv) to determine the conservation status of species based on national (NOM-059-SEMARNAT [Semarnat, 2010]) and international (IUCN, 2023) legislation, as well as the Environmental Vulnerability Score algorithm (Wilson, Johnson et al., 2013; Wilson, Mata-Silva et al., 2013). This work presents the updated herpetofauna formal list of the SGQBR, in addition to synthesizing information on the conservation status of the species. These studies are important because they are the basis for future research on NPAs with the objective of evaluating the effectiveness of their management plans, establishing conservation strategies based on the risk categories of the species and determining the priority of species to be conserved in the central region of Mexico.

Material and methods

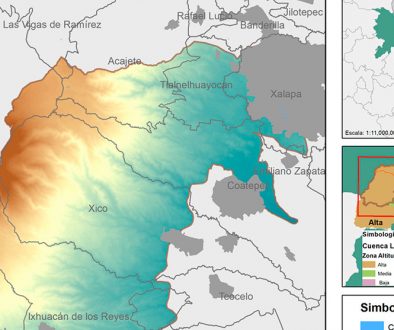

The study area corresponds to the SGQBR, located in the northeast of the state of Querétaro at the coordinates 20°50´ – 21°45’ N, and 98°50’ – 100°10’ W (Fig. 1). It has an area of 383,567.45 ha and is bordered to the north by the Santa María River, to the southeast by the Moctezuma River, to the west by the mountains formed by El Toro, Ojo de Agua, and El Infiernillo hills, and to the south by the Victoria-Xichú-Extoraz-Santa Clara River to the intersection with the Moctezuma River. The climate in the central portion is semi-warm-subhumid, to the southwest dry, semi-dry and semi-warm, and to the northwest and west are temperate subhumid with rains in summer (Zamudio et al., 1992). Depending on the region of the NPA, the temperature regime varies, registering an annual average of 18 °C. Likewise, the average rainfall is 313 mm in the dry season and up to 1,500 mm in the rainy season between July and October. The types of vegetation recorded are xerophilous scrub, tropical deciduous forest, pine forest, oak, pine-oak, cloud forest, riparian vegetation and there are also areas of extensive cultivation areas (Zamudio et al., 1992).

Information on records of species presence and their location was obtained from: i) records of species made in samplings in the reserve area (January 2021- May 2023), ii) various Mexican and foreign databases with records of amphibians and reptiles for Mexico (Appendix 1), consultation of the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF, 2019) website, and available databases of the Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (Conabio) projects (Appendix 1), and iii) consulted literature on richness and diversity of amphibians and reptiles for the state of Querétaro, and mainly the polygon of the SGQBR (Cruz-Elizalde et al., 2016, 2019; Cruz-Elizalde, Pineda-López et al., 2022; Cruz-Elizalde, Ramírez-Bautista et al., 2022; Dixon & Lemos-Espinal, 2010; Tepos-Ramírez et al., 2022, 2023). The records obtained from all these resources were reviewed and georeferenced using the ArcMap 10.8 program (ESRI, 2013). Because only the presence of species in the area was considered, the sources of information were considered sufficient. The records of species that showed doubtful distributions (Dixon & Lemos-Espinal, 2010; Frost, 2022; Tepos-Ramírez et al., 2023; Uetz et al., 2023) were removed from the analyses. The taxonomic update was based on the taxonomy followed by the Amphibian Species of the World website (Frost, 2023), and the Reptile Database (Uetz et al., 2023), where the most current taxonomic changes are summarized. Species richness was estimated by the presence of species in the polygon of the SGQBR, defined as alpha diversity (sensu Whittaker, 1972).

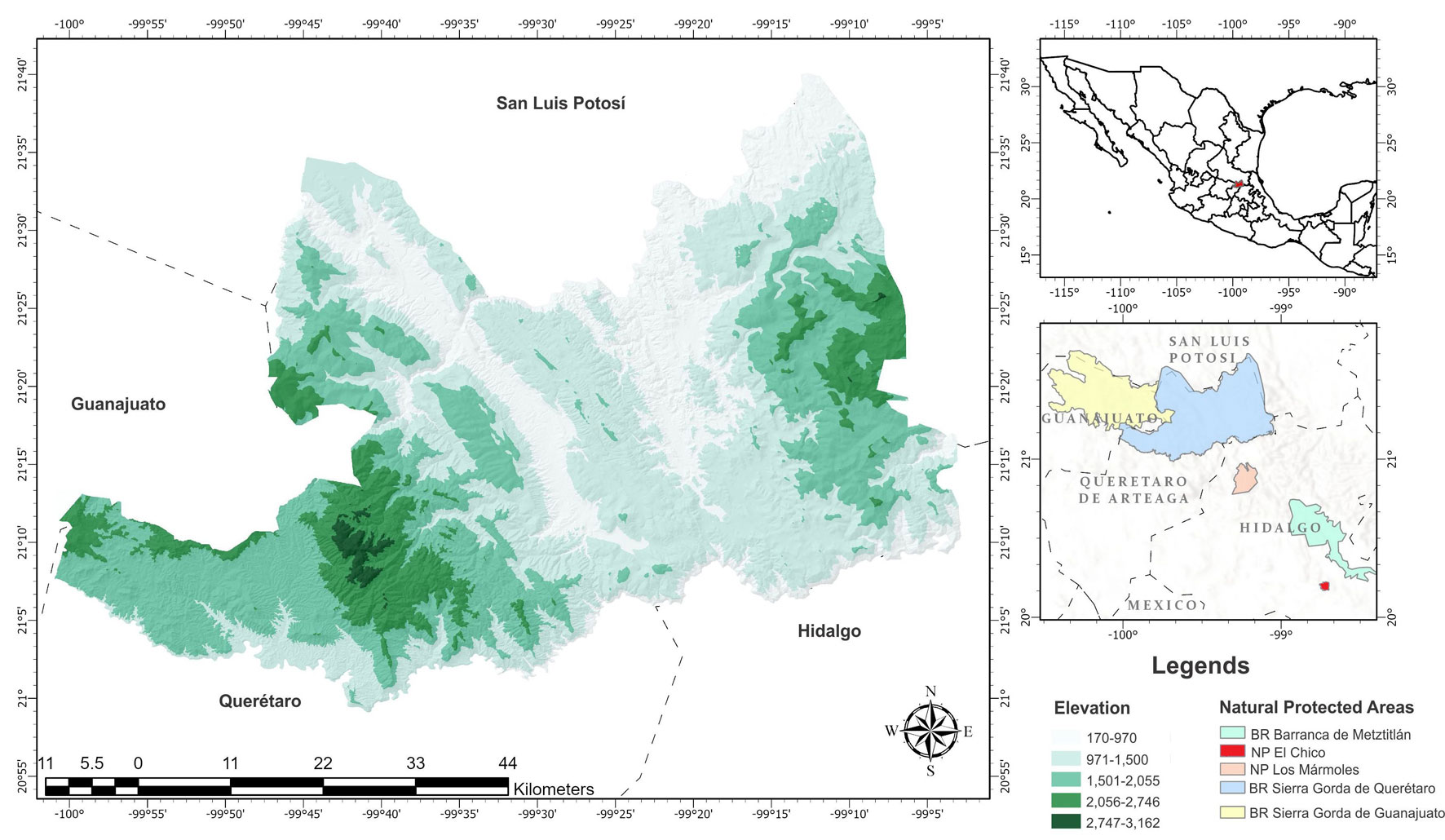

To compare the taxonomic diversity of the SGQBR with others NPAs in the central Mexico region, a regional list was generated considering the diversity of species contained in each NPA, which present complete lists and are close to the SGQBR. These NPAs correspond to the Sierra Gorda de Guanajuato Biosphere Reserve, Barranca de Metztitlán Biosphere Reserve, Los Mármoles National Park, and El Chico National Park (Table 1). These areas were considered because they are located in the vicinity of the SGQBR, they represent the main NPAs located in the central region of Mexico, and they are located in portions of the biogeographic provinces of central Mexico such as Sierra Madre Oriental, Central Mexican Plateau or Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt, generating a distinct diversity of species in central Mexico (Flores-Villela et al., 2010).

To assess taxonomic diversity for each NPA, the taxonomic distinctiveness of Warwick and Clarke (1995, 2001) was used, which calculates the mean (Delta = Δ⁺) and the variance (Lambda = Λ⁺; sensu Clarke & Warwick, 1998) of the taxonomic diversity of amphibians and reptiles from each NPA. This method assumes that a community with high phylogenetic relationships among its species will be less diverse (phylogenetically) than a community with low phylogenetic relationships among its species (Clarke & Warwick, 1998; Moreno et al., 2009; Warwick & Clarke, 1995). The formulas are Δ⁺ = [2ΣΣi < j ωij]/[S (S-1)] and Λ⁺ = [2ΣΣi < j (ωij-Δ⁺)²]/[S (S-1)], where ωij is the taxonomic distance between each pair of species i and j, and S is the number of observed species in the sampling (Warwick & Clarke, 1995). A high value of Δ⁺ reflects a low relationship among species, and therefore it is a measure of taxonomic diversity. However, Λ⁺ is not a measure of equity in the structure of the taxonomic diversity, thus a high value of Λ⁺ indicates under or over representation of the taxa in the sampling NPAs.

Table 1

Description of the Natural Protected Areas (NPAs) in central Mexico considered in this study.

| NPA | Category | Area (ha) | Date of decree |

| Sierra Gorda de Querétaro | Biosphere Reserve | 383,567.45 | 19 May 1997 |

| Sierra Gorda de Guanajuato | Biosphere Reserve | 236,882.76 | 2 February 2007 |

| Barranca de Metztitlán | Biosphere Reserve | 96,043 | 27 November 2000 |

| Los Mármoles | National Park | 23,150 | 8 September 1936 |

| El Chico | National Park | 2,739 | 6 July 1982 |

To detect differences in taxonomic diversity between the NPAs, the samples were compared (amphibians and reptiles by NPA) and the regional species pool was used to generate a null model with 1,000 resamplings (Clarke & Warwick, 1998). In this model, the average and variance of the sample numbers were used, and species were plotted with a confidence interval of 95% (Clarke & Warwick, 1998). We used NPAs with a minimum of 8 species to avoid the effect of high values of taxonomic diversity due to low species richness. To assess taxonomic diversity by each group we used the classification by Wilson, Johnson et al. (2013) and Wilson, Mata-Silva et al. (2013), which includes 5 taxonomic categories: species, genus, family, order, and class. The analysis was carried out with the PRIMER 5 program (Clarke & Gorley, 2001).

For each group, and between natural protected areas, beta diversity was calculated with a complementarity index that expressed the difference in the lists of species of 2 habitats: C = (Sj + Sk − 2Vjk/Sj + Sk – Vjk), where Sj and Sk are the number of species in habitats j and k, respectively, and Vjk is the number of species found in both habitats (Colwell & Coddington, 1994). The minimum value of C is 0, when the species lists are identical for the 2 habitats. A maximum value of 100 indicates that the lists are completely different.

Conservation status of the amphibians and reptiles was analyzed according to the NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 (Semarnat, 2010), the Red List of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN; updated May 2023), and the vulnerability environmental score index (EVS; Wilson, Johnson et al., 2013; Wilson, Mata-Silva et al., 2013). The EVS considers a score from 3 to 9 as low vulnerability, from 10 to 13 as moderate vulnerability, and from 14 to 20 as high vulnerability. The score uses information about the geographic distribution, extent of ecological distribution (vegetation types in which species occur), and the reproduction mode of amphibians or degree of human persecution in reptiles (Wilson, Johnson et al., 2013; Wilson, Mata-Silva et al., 2013).

Results

The herpetofauna of the SGQBR consists of 132 species. Amphibians are represented by 9 families, 20 genera, and 35 species, while for reptiles there are 20 families, 59 genera and 97 species. Within the amphibians, the Hylidae, Bufonidae, and Plethodontidae families have the greatest richness, with 8, 6 and 6 species, respectively; followed by Craugastoridae 4, Ranidae 4, Eleutherodactylidae 3, Scaphiopodidae 2 species, and Microhylidae and Ambystomatidae only 1 species (Table 2). For reptiles, lizard species are represented by 10 families, 16 genera, and 30 species. The family Phrynosomatidae is represented by 10 species, Anguidae and Scincidae with 4, Xantusiidae with 3, Corytophanidae, Teiidae, and Xenosauridae, each with 2, and the rest only have 1 species (Table 2). Finally, snake species are represented by 8 families and 40 genera; Colubridae and Dipsadidae are the most species rich with 25 and 16 species, respectively, followed by Natricidae with 9, Viperidae with 7, Leptotyphlopidae with 2, and the rest (Boidae, Elapidae, and Typhlopidae) with only 1 species each (Table 2). Finally, 5 species of turtles were recorded, 3 of the Emydidae family and 2 of the Kinosternidae family (Table 2).

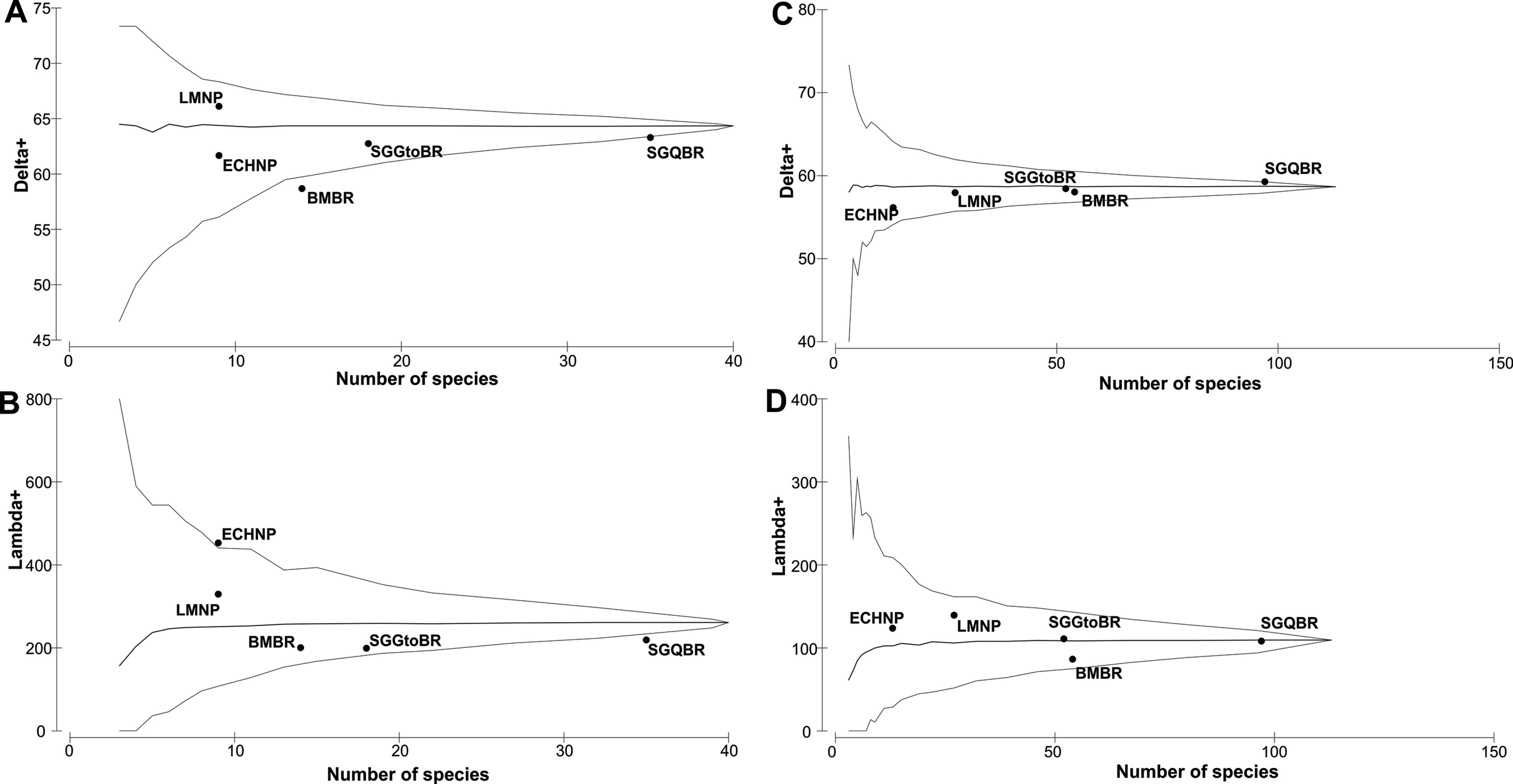

The SGQBR presents the highest species richness in both herpetofauna groups compared to the NPAs within the central region of Mexico (Table 3; Appendix 2). The values and the graph of taxonomic distinctiveness in amphibians show that SGQBR and the Sierra Gorda de Guanajuato Biosphere Reserve (SGGtoBR) are similar to the regional average (Fig. 2A, Table 3). Los Mármoles National Park (LMNP) presented the highest values of the taxonomic distinctiveness (Fig. 2A, Table 3). Also, considering the values of the variation of taxonomic distinctiveness, LMNP and BMBR show values close to the average (Fig. 2B, Table 3), and El Chico National Park (ECHNP) have the highest value, and the rest of the NPAs were near the 95% confidence interval expected by the model (except the SGQBR).

Table 2

Amphibians and reptiles of the Sierra Gorda de Querétaro Biosphere Reserve. Endemism (E = endemic, NE = not endemic); conservation status in Mexico according to NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 (Semarnat, 2010): P = in danger of extinction, A = threatened, Pr = subject to special protection; conservation status according to Red List (IUCN, 2023): Dd = data deficient; LC = Least concern, Vu = vulnerable, NT = near threatened; En = endangered; CR = critically endangered; Ne = not evaluated; population status (IUCN, 2023): environmental vulnerability score (EVS) according to Wilson, Johnson et al. (2013), Wilson, Mata-Silva et al. (2013), and Johnson et al. (2017): low (L) vulnerability species (score: 3-9); medium (M) vulnerability species (score: 10-13); and high (H) vulnerability species (score: 14-20); ** = non-native species/ introduced species; L* = low vulnerability as non-native species.

| Species | Endemism | NOM-059 | IUCN | Population status | EVS |

| Class Amphibia | |||||

| Order Anura | |||||

| Family Bufonidae (6 species) | |||||

| Anaxyrus compactilis | E | LC | Unknown | H (14) | |

| Anaxyrus punctatus | NE | LC | Stable | L (5) | |

| Incilius nebulifer | NE | LC | Stable | L (6) | |

| Incilius occidentalis | E | LC | Stable | M (11) | |

| Incilius valliceps | NE | LC | Stable | L (6) | |

| Rhinella horribilis** | NE | LC | Increasing | L* (3) | |

| Family Craugastoridae (4 species) | |||||

| Craugastor augusti | NE | LC | Stable | L (8) | |

| Craugastor decoratus | E | Pr | LC | Stable | H (15) |

| Craugastor pygmaeus | NE | LC | Unknown | L (9) | |

| Craugastor rhodopis | E | LC | Stable | H (14) | |

| Family Eleutherodactylidae (3 species) | |||||

| Eleutherodactylus guttilatus | NE | LC | Unknown | M (11) | |

| Eleutherodactylus longipes | E | LC | Unknown | H (15) | |

| Eleutherodactylus verrucipes | E | Pr | LC | Stable | H (16) |

| Family Hylidae (8 species) | |||||

| Dryophytes arenicolor | E | LC | Stable | L (7) | |

| Dryophytes eximius | E | LC | Stable | M (10) | |

| Rheohyla miotympanum | E | LC | Stable | L (9) | |

| Scinax staufferi | NE | LC | Stable | L (4) | |

| Smilisca baudinii | NE | LC | Stable | L (3) | |

| Tlalocohyla godmani | E | A | Vu | Decreasing | M (13) |

| Tlalocohyla picta | NE | LC | Increasing | L (8) | |

| Trachycephalus vermiculatus | NE | LC | Stable | L (4) | |

| Family Microhylidae (1 species) | |||||

| Hypopachus variolosus | NE | LC | Stable | L (4) | |

| Family Ranidae (4 species) | |||||

| Lithobates berlandieri | NE | Pr | LC | Stable | L (7) |

| Lithobates montezumae | E | Pr | LC | Decreasing | M (13) |

| Lithobates neovolcanicus | E | A | LC | Stable | M (13) |

| Lithobates spectabilis | E | LC | Decreasing | M (12) |

| Table 2. Continued | |||||

| Species | Endemism | NOM-059 | IUCN | Population status | EVS |

| Family Scaphiopodidae (2 species) | |||||

| Scaphiopus couchii | NE | LC | Stable | L (3) | |

| Spea multiplicata | NE | LC | Stable | L (6) | |

| Order Caudata | |||||

| Family Ambystomatidae (1 species) | |||||

| Ambystoma velasci | E | Pr | LC | Unknown | M (10) |

| Family Plethodontidae (6 species) | |||||

| Aquiloeurycea cephalica | E | A | LC | Decreasing | H (14) |

| Bolitoglossa platydactyla | E | Pr | LC | Stable | H (15) |

| Chiropterotriton chondrostega | E | Pr | En | Decreasing | H (17) |

| Chiropterotriton magnipes | E | Pr | En | Decreasing | H (16) |

| Chiropterotriton multidentatus | E | Pr | En | Stable | H (15) |

| Isthmura bellii | E | A | LC | Stable | M (12) |

| Class Reptilia | |||||

| Order Squamata | |||||

| Lizards | |||||

| Family Anguidae (4 species) | |||||

| Abronia taeniata | E | Pr | Vu | Decreasing | H (15) |

| Barisia ciliaris | E | Pr | LC | Unknown | H (14) |

| Gerrhonotus infernalis | E | LC | Stable | M (13) | |

| Gerrhonotus ophiurus | E | LC | Unknown | M (12) | |

| Family Corytophanidae (2 species) | |||||

| Corytophanes hernandesii | NE | Pr | LC | Stable | M (13) |

| Laemanctus serratus | NE | Pr | LC | Stable | L (8) |

| Family Dactyloidae (1 species) | |||||

| Anolis sericeus | NE | LC | Stable | L (8) | |

| Family Dibamidae (1 species) | |||||

| Anelytropsis papillosus | E | A | LC | Decreasing | M (10) |

| Family Gekkonidae (1 species) | |||||

| Hemidactylus frenatus** | NE | LC | Stable | L* (8) | |

| Family Phrynosomatidae (10 species) | |||||

| Phrynosoma orbiculare | E | A | LC | Stable | M (12) |

| Sceloporus aeneus | E | LC | Stable | M (13) | |

| Sceloporus exsul | E | A | CR | Decreasing | H (17) |

| Sceloporus grammicus | NE | Pr | LC | Stable | L (9) |

| Sceloporus minor | E | LC | Stable | H (14) | |

| Sceloporus parvus | E | LC | Stable | H (15) | |

| Sceloporus scalaris | E | LC | Stable | M (12) | |

| Sceloporus spinosus | E | LC | Stable | M (12) | |

| Sceloporus torquatus | E | LC | Stable | M (11) | |

| Sceloporus variabilis | NE | LC | Stable | L (5) | |

| Family Scincidae (4 species) | |||||

| Plestiodon lynxe | E | Pr | LC | Stable | M (10) |

| Plestiodon tetragrammus | NE | LC | Stable | M (12) | |

| Scincella gemmingeri | E | LC | Stable | M (11) | |

| Scincella silvicola | E | A | LC | Stable | M (12) |

| Family Teiidae (2 species) | |||||

| Aspidoscelis gularis | NE | LC | Stable | L (9) | |

| Holcosus amphigrammus | E | LC | Stable | M (11) | |

| Family Xantusiidae (3 species) | |||||

| Lepidophyma gaigeae | E | Pr | Vu | Decreasing | M (13) |

| Lepidophyma occulor | E | Pr | LC | Stable | H (14) |

| Lepidophyma sylvaticum | E | Pr | LC | Decreasing | M (11) |

| Family Xenosauridae (2 species) | |||||

| Xenosaurus mendozai | E | Ne | Unknown | H (16) | |

| Xenosaurus newmanorum | E | Pr | En | Decreasing | H (15) |

| Snakes | |||||

| Family Boidae (1 species) | |||||

| Boa imperator | NE | A | LC | Stable | M (10) |

| Family Colubridae (25 species) | |||||

| Conopsis lineata | E | LC | Stable | M (13) | |

| Conopsis nasus | E | LC | Stable | M (11) | |

| Drymarchon melanurus | NE | LC | Stable | L (6) | |

| Drymobius margaritiferus | NE | LC | Stable | L (6) | |

| Ficimia olivacea | E | LC | Unknown | L (9) | |

| Ficimia streckeri | NE | LC | Stable | M (12) | |

| Gyalopion canum | NE | LC | Stable | L (9) | |

| Lampropeltis polyzona | E | A | LC | Unknown | M (11) |

| Lampropeltis ruthveni | E | A | NT | Decreasing | H (16) |

| Leptophis mexicanus | NE | A | LC | Stable | L (6) |

| Masticophis mentovarius | E | A | LC | Unknown | L (6) |

| Masticophis schotti | NE | LC | Stable | M (13) | |

| Masticophis taeniatus | NE | LC | Stable | M (10) | |

| Mastigodryas melanolomus | NE | LC | Stable | L (6) | |

| Oxybelis potosiensis | E | Ne | Unknown | L (5) | |

| Pantherophis emoryi | NE | LC | Stable | M (13) | |

| Pituophis deppei | E | A | LC | Stable | H (14) |

| Pliocercus elapoides | NE | LC | Stable | M (10) | |

| Scaphiodontophis annulatus | NE | LC | Stable | M (11) | |

| Salvadora lineata | NE | LC | Stable | M (10) | |

| Senticolis triaspis | NE | LC | Stable | L (6) | |

| Spilotes pullatus | NE | LC | Stable | L (6) | |

| Tantilla bocourti | E | LC | Unknown | L (9) | |

| Tantilla rubra | NE | Pr | LC | Unknown | L (5) |

| Trimorphodon tau | E | LC | Stable | M (13) | |

| Family Dipsadidae (16 species) | |||||

| Adelphicos quadrivirgatum | NE | LC | Unknown | M (10) | |

| Amastridium sapperi | NE | LC | Stable | M (10) | |

| Chersodromus rubriventris | E | Pr | En | Decreasing | H (14) |

| Coniophanes fissidens | NE | LC | Stable | L (7) | |

| Coniohanes imperialis | NE | Ne | Unknown | L (8) | |

| Coniophanes taeniatus | E | Ne | Unknown | L (7) | |

| Diadophis punctatus | NE | LC | Stable | L (4) | |

| Geophis latifrontalis | E | Pr | Dd | Unknown | H (14) |

| Geophis mutitorques | E | Pr | LC | Stable | M (13) |

| Geophis sartorii | NE | Pr | LC | Stable | L (9) |

| Hypsiglena jani | NE | Pr | LC | Stable | L (6) |

| Hypsiglena tanzeri | E | Dd | Unknown | L (6) | |

| Imantodes gemmistratus | NE | Pr | LC | Stable | L (6) |

| Leptodeira septentrionalis | NE | LC | Stable | L (8) | |

| Ninia diademata | NE | LC | Stable | L (9) | |

| Rhadinaea gaigeae | E | Dd | Unknown | M (12) | |

| Family Elapidae (1 species) | |||||

| Micrurus tener | NE | LC | Stable | M (11) | |

| Family Leptotyphlopidae (2 species) | |||||

| Epictia wynni | E | Ne | Unknown | M (13) | |

| Rena dulcis | NE | LC | Unknown | H (16) | |

| Family Natricidae (9 species) | |||||

| Storeria dekayi | NE | LC | Stable | L (7) | |

| Storeria hidalgoensis | E | Vu | Decreasing | M (13) | |

| Storeria storerioides | E | LC | Stable | M (11) | |

| Thamnophis cyrtopsis | NE | A | LC | Stable | L (7) |

| Thamnophis eques | NE | A | LC | Stable | L (8) |

| Thamnophis melanogaster | E | A | En | Decreasing | H (15) |

| Thamnophis pulchrilatus | E | LC | Unknown | H (15) | |

| Thamnophis scalaris | E | A | LC | Stable | H (14) |

| Thamnophis sumichrasti | E | A | LC | Unknown | H (15) |

| Family Typhlopidae (1 species) | |||||

| Indotyphlops braminus | NE | LC | Increasing | H (17) | |

| Family Viperidae (7 species) | |||||

| Bothrops asper | NE | LC | Stable | M (12) | |

| Crotalus aquilus | E | Pr | LC | Decreasing | H (16) |

| Crotalus atrox | NE | Pr | LC | Stable | L (9) |

| Crotalus molossus | NE | Pr | LC | Stable | L (8) |

| Crotalus scutulatus | NE | Pr | LC | Stable | M (11) |

| Crotalus totonacus | E | LC | Stable | H (17) | |

| Metlapilcoatlus borealis | E | Ne | Unknown | H (18) | |

| Order Testudines | |||||

| Family Emydidae (3 species) | |||||

| Graptemys pseudogeographica | NE | LC | Unknown | H (17) | |

| Trachemys scripta** | NE | Pr | LC | Stable | L* (8) |

| Trachemys venusta** | NE | Ne | Unknown | L*(8) | |

| Family Kinosternidae (2 species) | |||||

| Kinosternon hirtipes | NE | Pr | LC | Decreasing | M (10) |

| Kinosternon integrum | E | Pr | LC | Stable | M (11) |

In reptiles, all areas showed values within the confidence interval expected by the model, as well as values close to the regional average (Fig. 2C). The Sierra Gorda de Guanajuato Biosphere Reserve (SGGtoBR), LMNP, Barranca de Metztitlán Biosphere Reserve (BMBR) and SGQBR were the closest to the regional average. In the case of variation of taxonomic distinctiveness, most of these areas present variation in the position respect to taxonomic distinctiveness; however, in general, they show values close to the average (Fig. 2D, Table 3), and are within the 95% confidence interval expected by the model (Fig. 2D, Table 3).

In amphibians, the highest percentages of complementarity between NPAs were presented (at least higher than 71%) registering the highest percentages between ECHNP and SGQBR, and the lowest values between BMBR and SGGtoBR (Table 4). In amphibians, the SGQBR presented the lowest percentage of complementarity when is compared with the BMBR (48.57%), and the rest of the associations with percentages between 63.89 and 87.18% (Table 4).

In reptiles, only 4 associations stand out with percentages of completeness greater than 76%. The SGQBR and ECHNP presented the highest values with 91.09%, followed by SGGtoBR-ECHNP with 81.82%, BMBR-ECHNP with 80.36%, and finally LMNP-SGQBR with 76% (Table 4). The rest of the associations presented values between 55.19 and 66.67% (Table 4).

In amphibians, different risk categories were found between both national and international agencies (Tables 2, 5). There is a greater number of endemic species (20) than non-endemic (15). In NOM-059, 9 species were classified as subject to special protection, and 4 were threatened (Tlalocohyla godmani, Lithobates neovolcanicus, Aquiloeurycea cephalica, and Isthmura bellii), and the rest of the species (22) were not evaluated (Tables 2, 5). According to the IUCN, 31 species are of least concern, 3 as endangered (Chiropterotriton chondrostega, C. magnipes, and C. multidentatus) and only T. godmani as vulnerable. Most of the species (22) have a stable population status, and according to the EVS, 16 species have low environmental vulnerability, 9 with medium vulnerability, and 10 with high vulnerability (Table 5).

For reptiles, there was a greater number of endemic species (49) than non-endemic (48). In the NOM-059, 24 species were classified as subject to special protection, 15 as threatened, and the rest of the species (58) are not evaluated (Tables 2, 5). According to the IUCN, 79 species are of least concern, 3 endangered (Xenosaurus newmanorum, Chersodromus rubriventris, and Thamnophis melanogaster), 3 as vulnerable (Abronia taeniata, Lepidophyma gaigeae, and Storeria hidalgoensis), and Sceloporus exsul as critically endangered (Table 2). The rest are found as not evaluated or with deficient data. Most of the species (62) have a stable population status, and according to the EVS, 35 species have low environmental vulnerability, 40 medium vulnerability, and 22 high vulnerability (Tables 2, 5).

Discussion

The SGQBR has the greatest richness and diversity of species of reptiles and amphibians for the central region of Mexico, which was greater than other widely analyzed NPAs (Cruz-Elizalde et al., 2015; Flores-Villela et al., 2010). The region that makes up the SGQBR polygon is mostly composed of desertic and temperate montane environments, where a high diversity of species of amphibian and reptile families have been reported. At the regional level, the species richness in the SGQBR is greater than other areas such as the BMBR, or the LMNP and ECHNP, areas that occur in regions with arid and semi-arid, temperate, and tropical environments, in addition to portions of provinces such as Sierra Madre Oriental and Central Plateau (Ramírez-Bautista et al., 2020). In these environments and mainly in the central region of Mexico, the distribution areas of families and genera of amphibians such as Craugastor, Eleutherodactylus, Dryophytes, Aquiloeurycea, and Chiropterotriton occur, which present a high number of species and endemism in this region (Canseco-Márquez et al., 2004; Flores-Villela et al., 2010).

Table 3

Species richness and values of average of taxonomic distinctiveness (Delta+) and variance in taxonomic distinctiveness (Lambda+) of amphibians and reptiles from the NPAs analyzed.

| Natural Protected Area | Species richness | Delta+ | Lambda+ | |||

| Amphibians | Reptiles | Amphibians | Reptiles | Amphibians | Reptiles | |

| Sierra Gorda de Querétaro Biosphere Reserve | 35 | 97 | 63.29 | 59.26 | 219.06 | 108.22 |

| Sierra Gorda de Guanajuato Biosphere Reserve | 18 | 52 | 62.75 | 58.43 | 199 | 110.96 |

| Barranca de Metztitlán Biosphere Reserve | 14 | 54 | 58.68 | 58.03 | 200.46 | 86.40 |

| Los Mármoles National Park | 9 | 27 | 66.11 | 57.95 | 329.32 | 139.38 |

| El Chico National Park | 9 | 13 | 61.67 | 56.15 | 452.78 | 123.67 |

Table 4

Percentages of complementarity and shared species of amphibians and reptiles between NPAs in central Mexico. SGGtoBR = Sierra Gorda de Guanajuato Biosphere Reserve, SGQBR = Sierra Gorda de Querétaro Biosphere Reserve, BMBR = Barranca de Metztitlán Biosphere Reserve, LMNP = Los Mármoles National Park, ECHNP = El Chico National Park.

| Amphibians | |||||

| Natural Protected Areas | SGGtoBR | SGQBR | BMBR | LMNP | ECHNP |

| SGGtoBR | 18 | 12 | 6 | 4 | |

| SGQBR | 48.57 | 13 | 6 | 5 | |

| BMBR | 40 | 63.89 | 6 | 4 | |

| LMNP | 71.43 | 84.21 | 64.71 | 3 | |

| ECHNP | 82.61 | 87.18 | 78.95 | 80 | |

| Reptiles | |||||

| Natural Protected Areas | SGGtoBR | SGQBR | BMBR | LMNP | ECHNP |

| SGGtoBR | 45 | 32 | 21 | 10 | |

| SGQBR | 56.73 | 46 | 24 | 9 | |

| BMBR | 56.76 | 56.19 | 20 | 11 | |

| LMNP | 63.79 | 76 | 67.21 | 10 | |

| ECHNP | 81.82 | 91.09 | 80.36 | 66.67 |

The northern portions of the SGQBR are represented by tropical environments, which correspondingly contain a distinctly tropical composition in their amphibian fauna, which is different from that found in the central and southern portions of the region. For example, species such as Hypopachus variolosus and Trachycephalus vermiculatus occur in these regions, as well as reptiles of the Lepidophyma genus such as L. occulor, L. gaigeae and L. sylvaticum, species with a Neotropical origin (Lemos-Espinal et al., 2018). This tropical association is mainly represented by the composition of families in amphibians and reptiles, since in temperate regions such as pine, oak, or pine-oak forests, the families Hylidae, Craugastoridae or Plethodontidae present the richest and most diverse sites, at least in the Querétaro State region (Cruz-Elizalde et al., 2019; Cruz-Elizalde, Ramírez-Bautista et al., 2022; Tepos-Ramírez et al., 2023).

Table 5

Summary of number of species of amphibians and reptiles of the Sierra Gorda de Querétaro Biosphere Reserve in different categories of conservation. Conservation status in Mexico according to the NOM-059-SEMARNAT (Semarnat, 2010): A = threatened, Pr = subject to special protection, Ne = Not evaluated); conservation status according to the Red List (IUCN, 2023): Dd = data deficient; LC = least concern, Vu = vulnerable, NT = near threatened; En = endangered; CR = critically endangered; Ne = not evaluated); population status according to IUCN (2023): environmental vulnerability score (EVS, low vulnerability species [L, 3-9], medium vulnerability species [M, 10-13], and high vulnerability species [H, 14-20] according to Wilson, Johnson et al. [2013], Wilson, Mata-Silva et al. [2013], and Johnson et al. [2017]).

| Group | Endemism | NOM-059 | IUCN Red List | Population status | EVS | |||||

| Amphibians | Endemic | 20 | A | 4 | En | 3 | Decreasing | 6 | L | 16 |

| No endemic | 15 | Pr | 9 | LC | 31 | Increasing | 2 | M | 9 | |

| Ne | 22 | Vu | 1 | Stable | 22 | H | 10 | |||

| Ne | – | Unknown | 5 | |||||||

| Dd | – | |||||||||

| Reptiles | Endemic | 49 | A | 15 | CR | 1 | Decreasing | 12 | L | 35 |

| No endemic | 48 | Pr | 24 | En | 3 | Increasing | 1 | M | 40 | |

| Ne | 58 | LC | 79 | Stable | 62 | H | 22 | |||

| Vu | 3 | Unknown | 22 | |||||||

| NT | 1 | |||||||||

| Ne | 7 | |||||||||

| Dd | 3 |

In addition to the biogeographical considerations, ecological factors such as the different altitude levels (from 260 to 3,100 m asl) in the mountainous region of the SGQBR can explain the remarkable diversity of species. For example, Tepos-Ramírez, Pineda-López et al. (2021) established an altitudinal cline that goes from 1,000 to 3,100 m asl, which determines the elevational distribution patterns of amphibians and reptiles. In this study, species of the genus Sceloporus (S. torquatus, S. scalaris, S. minor, S. grammicus or S. dugesii) are better represented in environments from 2,200 to 3,000 m asl, which coincides with the highest occurrence of temperate montane environments. The cloud forest regions occupy a small portion of the territory; however, it is well known that a remarkable diversity of amphibian and reptile species and endemism occurs in these sites (García-Castillo et al., 2018). For example, cloud forest habitat is known to possess high species richness and endemism in salamanders of the genera Pseudoeurycea, Cryptotriton, Aquiloeurycea, and Thorius (Ochoa-Ochoa et al., 2017; Rovito et al., 2015). In the cloud forest portion of the reserve, there is a high number of amphibians, mainly salamanders such as the species Aquiloeurycea cephalica, Chiropterotriton chondrostega, C. magnipes or C. multidentatus. These species represent the characteristic elements of high diversity and endemism in the case of the group of caudate amphibians (García-Padilla et al., 2021), groups with high values of endemism in the mountainous regions of Mexico.

In the case of reptiles, the best represented snake families in the SGQBR are Colubridae, Dipsadidae, Natricidae, and Viperidae. These families contain genera that present the main centers of endemism towards the central region of Mexico. For example, in the case of species of the genus Crotalus, different authors such as Paredes-García et al. (2011), or Bryson et al. (2011, 2014), indicate that the central region of Mexico, mainly the mountain regions, presents the centers with the highest number of endemism and diversity of species. This same pattern occurs for other groups such as snakes of the genus Thamnophis (Hallas et al., 2022), Geophis (Grünwald et al., 2021; Wilson & Townsend, 2007), Rhadinaea (García-Sotelo et al., 2021) or Lampropeltis (Burbrink et al., 2022). Also, in the case of lizards, in these regions the distribution of groups such as Xenosaurus (Nieto-Montes de Oca et al., 2017), Sceloporus (Leaché et al., 2016), Plestiodon and Scincella is presented in the same way (Brandley et al., 2012).

The remarkable diversity of species, genera and families contained in the SGQBR is comparable to that reported for the rest of the NPAs we analyzed. At a regional scale, the pool of species is characteristic of what is contained within the regions of central Mexico, and in temperate mountain, and arid and semi-arid environments. This conformation gives rise to a mixture of elements endemic to mountain regions, both amphibians and reptiles (Canseco-Márquez et al., 2004). The LMNP and SGGtoBR, unlike the SGQBR, contain the highest values of taxonomic diversity, despite not necessarily containing the greatest species richness for both herpetofauna groups (Appendix 2). However, this taxonomic diversity is better represented by the SGQBR, since in both groups it presents values close to the average generated by the model. The different conformation of species in the amphibian and reptile communities of the region, notably influence the richness contained for the NPAs analyzed, and particularly for that of the SGQBR, since, as the generated values show, its richness is representative of that contained in the central region of Mexico (Cruz-Elizalde et al., 2019; Cruz-Elizalde, Ramírez-Bautista et al., 2022; Dixon & Lemos-Espinal, 2010; Ramírez-Bautista et al., 2009, 2014).This association is better understood by analyzing the complementarity in the composition of species between NPAs, where the 3 Biosphere Reserves have the highest percentages in contrast to the National Parks.

For amphibians, there are the higher values of complementarity, indicating that the species composition between NPAs is different, thus in terms of regional connectivity, and maintenance of amphibian diversity at a regional scale, these NPAs contain a high diversity of species. For reptiles, the pattern of complementarity is less marked for the combinations between NPAs, however, it stands out that the SGQBR presents high percentages of complementarity mainly with the National Parks and with the SGGtoBR, which is adjacent to the SGQBR. This result indicates, on the one hand, that the composition of species, even at close regional scales, can differ substantially, mainly due to microenvironmental conditions, and highlights the need for regional studies aimed at inventorying herpetofaunal diversity.

The conservation status of the species of SGQBR through the various national and international agencies, indicates a high representation of species with notable conservation categories, which are centered on amphibian species of the genera Aquiloeurycea, Pseudoeurycea, and Chiropterotriton (García-Padilla et al., 2021). These species, in addition to those of the Hylidae family such as Dryophytes arenicolor, D. eximius, Rheohyla miotympanum, Smilisca baudinii, and Tlalocohyla godmani, are conservation categories of concern according to the IUCN, NOM-059 and within the EVS. Like amphibians, different species of reptiles, mainly lizards of the genus Lepidophyma, Sceloporus, and Abronia present the highest values in conservation categories. This status is like that of species of the genus Crotalus, which are frequently killed or trafficked because they are poisonous (Fitzgerald et al., 2004). Likewise, the effect of fragmentation and disturbance affects the occurrence of endemic and low-distribution species, such as the case of the snakes Chersodromus rubriventris, Thamnophis melanogaster, Storeria hidalgoensis or Amastridium sapperi (Lara-Tufino et al., 2014; Ramírez-Bautista et al., 2013).

The richness of species, as well as the list of amphibians and reptiles recorded in this study, fill an important information gap regarding the herpetofauna of the Sierra Gorda de Querétaro Biosphere Reserve. Likewise, it is necessary to carry out a greater number of studies focused not only on determining the species richness of both groups, but also on analyzing the ecological and functional attributes of the species, in addition to regional analyses such as ecological niche modeling to analyze changes in the spatial distribution of species due to, for example, climate change (future scenarios). This will aid in the study of the different components of diversity of the reserve, for both its functional richness and diversity functions, and through this, the development of appropriate conservation strategies for amphibians and reptiles (Devictor et al., 2010).

The SGQBR has a notable variety of types of vegetation, but also has different land uses. Although large extensions of natural cover can be found, mainly in the northern region with pine, oak, pine-oak forests, cloud forest and tropical vegetation, many of these areas are surrounded, and in different cases fragmented by farming areas, pastures, and human settlements.

In recent studies, a high richness and diversity of anurans have been recorded in transformed environments or with anthropic effect such as annual seasonal crop agriculture and induced pasture in the northern and central portion of the region that corresponds to the reserve (Cruz-Elizalde, Pineda-López et al., 2022). These environments make up a high portion of the territory both inside and outside the reserve. This emphasizes the need to evaluate the current conservation measures in the buffer zones and core zones, since, within the buffer zone, the degree of disturbance has increased, putting at risk the biodiversity in this zone, and secondarily impacts the core zones (Íñiguez Dávalos et al., 2014; Tepos-Ramírez, Pineda-López et al., 2021).

The environments modified by anthropic effect such as cultivated areas and induced pasture have registered a high species richness and functional richness, at least in anurans (Cruz-Elizalde, Pineda-López et al., 2022; Leyte-Manrique, Balderas-Valdivia et al., 2022). However, the composition of species in these areas is mostly made up of generalist species that are highly tolerant to disturbance, such as the species Rhinella horribilis, Anaxyrus compactilis, A. punctatus, Lithobates berlandieri or L. spectabilis (Cruz-Elizalde, Pineda-López et al., 2022; Leyte-Manrique, Balderas-Valdivia et al., 2022; Leyte-Manrique, Mata-Silva et al., 2022). These species make up most of the communities in environments in the buffer zone of the reserve, and, on the contrary, species of the Hylidae family, such as Scinax staufferi, Tlalocohyla godmani, Rheohyla miotympanum, inhabit the core areas or in sites with greater vegetation cover, as well as salamanders such as Aquiloeurycea cephalica, Isthmura bellii, Chiropterotriton chondrostega, C. magnipes, and C. multidentatus (Cruz-Elizalde, Ramírez-Bautista et al., 2022). These last species present a decrease of the populations due to transformation of the environment, loss of vegetation cover, contamination and myths and beliefs on the part of the local populace, of those that occur in the core and buffer zones in the reserve.

The pattern of species loss in amphibians has been similarly reported in the case of reptiles. Even though there are highly tolerant species and even those that benefit from habitat modification, many narrow distribution species (particularly snakes), are decreasing in abundance because of the transformation of the environment and to mortality caused by local myths and beliefs. Among the main groups affected are snakes of the genera Crotalus, Chersodromus, Thamnophis or Lampropeltis, and lizards the genera Abronia, Gerrhonotus, Barisia, and Lepidophyma.

Different conservation measures and planning have been established in the NPAs of Mexico, which are generally applied in the SGQBR, which mainly include: 1) characterization and description of the biophysical and socioeconomic environment, 2) the diagnosis and problem of protected area based on the evaluation of local, municipal and regional socioeconomic development, 3) planning, derived from the processes of diagnosis and social participation to achieve the objectives of the protected area organized in direct and indirect conservation subprograms, 4) zoning, generated from the evaluation of the biological, ecological and use characteristics of, as well as the current territorial regulations, 5) the application and monitoring of the regulations that define the legal elements derived from the decree of establishment of the protected area, of the category, the legislation, and the applicable Official Mexican Norms, among others, to regulate the activities carried out in the area, and 6) the evaluation of the functional integration of the system (Íñiguez-Dávalos et al., 2014).

Different factors are important to determine new conservation strategies in the SGQBR. This is necessary because the reserve presents, among other attributes, a notable diversity of amphibians and reptiles, a high number of species in notable conservation categories, the restriction of endemic species to portions of temperate and tropical forests, in addition to a high degree and accelerated transformation of the environment. In this context, we consider necessary the application of various measures to improve the knowledge and appreciation of the herpetofauna in the reserve, as well as to generate new information. These measures are: 1) carry out inventories of the diversity of herpetofauna in sites with remnants of natural vegetation, 2) analyze the effect of land use change within the reserve area, 3) carry out environmental education plans with the inhabitants of the settlements within the reserve, 4) establish population monitoring programs of herpetofauna species, and 5) analyze connectivity on a regional scale to maintain large portions of vegetation that serve to maintain populations of amphibians and reptiles, and other biological groups.

Acknowledgments

We thank to the curators of the Colección Herpetológica at the Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo, Colección Nacional de Anfibios y Reptiles (CNAR) at the Instituto de Biología, and the Colección de Anfibios y Reptiles of the Museo de Zoología “Alfonso L. Herrera”, Facultad de Ciencias, both from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), for access to their collections. To the staff of the Sierra Gorda Biosphere Reserve for the logistical support. To the owners who allowed us access to their properties in the region bordering the state of Hidalgo. This study was supported in part by project Red Temática Biología, Manejo y Conservación de Fauna Nativa en Ambientes Antropizados, Project #271845 supported by Conacyt, and Conanp PROREST/ETM/40/2022. Collecting permits (SEMARNAT SGPA/DGVS/00770/22 and SGPA/DGVS/00769/22) were issued to RCE. We thank the Cuerpo Académico de Ecología y Diversidad Faunística from the Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro. To Diana Elizabeth García Hernández for her support, and to Erick Daniel Velasco Esquivel, and Salvador Zamora Ledesma for his logistical support. Finally, we are thankful to Scott Gillingwater for facilitating literature and two anonymous reviewers for a critical review of this manuscript.

Appendix 1. National and foreign database collections consulted with records of amphibian and reptile species from the Sierra Gorda de Querétaro Biosphere Reserve, Mexico.

| Collection | Country |

| Colección Herpetológica Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas, UAEH | Mexico |

| Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (Conabio) | Mexico |

| Colección Nacional de Anfibios y Reptiles de la Facultad de Ciencias del Instituto de Biología, UNAM | Mexico |

| Museo de Zoología de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México MZFC | Mexico |

| Collection of Vertebrates, University of Texas at Arlington UTA | USA |

| Collection of Herpetology, University of California at Berkeley Museum of Vertebrate Zoology MVZ | USA |

| Collection Herpetology, Texas Cooperative Wildlife Collection, Texas A and M University TCWC | USA |

| Collection Herpetology, Oklahoma Museum of Natural History University of Oklahoma OMNH | USA |

| Collection of Herpetology, Zoology Section of Los Angeles Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History LACM | USA |

| Collection of Herpetology, University of Illinois Museum of Natural History UIMNH | USA |

| Collection of Herpetology, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University MCZ | USA |

| The University of Michigan Museum of Zoology UMMZ | USA |

Appendix 2. Species list of the regional diversity of amphibians and reptiles from the 5 NPAs analyzed. SGGtoBR = Sierra Gorda de Guanajuato Biosphere Reserve, SGQBR = Sierra Gorda de Querétaro Biosphere Reserve, BMBR = Barranca de Metztitlán Biosphere Reserve, LMNP = Los Mármoles National Park, ECHNP = El Chico National Park. 1 = ocurrence.

| Class | Order | Family | Species | SGQBR | SGGtoBR | BMBR | LMNP | ECHNP |

| Amphibia | Anura | Bufonidae | Anaxyrus compactilis | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| A. punctatus | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Incilius nebulifer | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| I. occidentalis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| I. valliceps | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Rhinella horribilis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Craugastoridae | Craugastor augusti | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||

| C. decoratus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| C. pygmaeus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| C. rhodopis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Eleutherodactylidae | Eleutherodactylus guttilatus | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| E. longipes | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| E. verrucipes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Hylidae | Dryophytes arenicolor | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||

| D. eximius | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||

| D. plicatus | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Rheohyla miotympanum | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Appendix 2. Continued | ||||||||

| Class | Order | Family | Species | SGQBR | SGGtoBR | BMBR | LMNP | ECHNP |

| Scinax staufferi | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Smilisca baudinii | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Tlalocohyla godmani | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| T. picta | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Trachycephalus vermiculatus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Microhylidae | Hypopachus variolosus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Ranidae | Lithobates berlandieri | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| L. montezumae | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| L. neovolcanicus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| L. spectabilis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Scaphiopodidae | Scaphiopus couchii | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Spea multiplicata | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Caudata | Ambystomatidae | Ambystoma velasci | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Plethodontidae | Aquiloeurycea cephalica | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Bolitoglossa platydactyla | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Chiropterotriton chico | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||

| C. chondrostega | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| C. dimidiatus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||

| C. magnipes | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| C. mosaueri | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| C. multidentatus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Isthmura bellii | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Pseudoeurycea altamontana | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Reptilia | Squamata (Lizards) | Anguidae | Abronia taeniata | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Barisia ciliaris | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| B. imbricata | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Gerrhonotus infernalis | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| G. liocephalus | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| G. ophiurus | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Corytophanidae | Corytophanes hernandesii | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Laemanctus serratus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Dactyloidae | Anolis sericeus | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Dibamidae | Anelytropsis papillosus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Gekkonidae | Hemidactylus frenatus | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Phrynosomatidae | Holbrookia maculata | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Phrynosoma orbiculare | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Sceloporus aeneus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| S. bicanthalis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||

| S. exsul | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| S. grammicus | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| S. minor | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| S. mucronatus | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||

| S. parvus | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| S. scalaris | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| S. spinosus | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| S. torquatus | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| S. variabilis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Scincidae | Plestiodon lynxe | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| P. tetragrammus | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Scincella gemmingeri | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| S. silvicola | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Teiidae | Aspidoscelis gularis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Holcosus amphigrammus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Xantusiidae | Lepidophyma gaigeae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| L. occulor | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| L. sylvaticum | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Xenosauridae | Xenosaurus mendozai | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| X. newmanorum | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Squamata (Snakes) | Boidae | Boa imperator | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Colubridae | Conopsis lineata | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| C. nasus | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Drymarchon melanurus | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Drymobius margaritiferus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Ficimia hardyi | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| F. olivacea | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| F. streckeri | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Gyalopion canum | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Lampropeltis annulata | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| L. mexicana | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| L. polyzona | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| L. ruthveni | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Leptophis mexicanus | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Masticophis flagellum | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| M. mentovarius | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| M. schotti | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| M. taeniatus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Mastigodryas melanolomus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Oxybelis microphthalmus | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| O. potosiensis | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Pantherophis emoryi | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Pituophis deppei | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Pliocercus elapoides | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Scaphiodontophis annulatus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Salvadora bairdi | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| S. lineata | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Senticolis triaspis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Spilotes pullatus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Tantilla bocourti | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| T. rubra | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Trimorphodon tau | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Dipsadidae | Adelphicos quadrivirgatum | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Amastridium sapperi | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Chersodromus rubriventris | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Coniophanes fissidens | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| C. imperialis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| C. taeniatus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Diadophis punctatus | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Geophis latifrontalis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| G. mutitorques | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| G. sartorii | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| G. semidoliatus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Hypsiglena jani | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| H. tanzeri | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Imantodes gemmistratus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Leptodeira maculata | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| L. septentrionalis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Ninia diademata | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Rhadinaea gaigeae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| R. taeniata | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Elapidae | Micrurus tener | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Leptotyphlopidae | Epictia wynni | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Rena dulcis | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Natricidae | Nerodia rhombifer | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Storeria dekayi | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| S. hidalgoensis | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| S. storerioides | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Thamnophis cyrtopsis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| T. eques | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| T. melanogaster | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| T. proximus | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| T. pulchrilatus | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||

| T. scalaris | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| T. sumichrasti | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Typhlopidae | Indotyphlops braminus | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Viperidae | Bothrops asper | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Crotalus aquilus | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| C. atrox | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| C. molossus | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| C. scutulatus | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| C. totonacus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Metlapilcoatlus borealis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Testudines | Emydidae | Graptemys pseudogeographica | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Trachemys scripta | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| T. venusta | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Kinosternidae | Kinosternon hirtipes | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| K. integrum | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

References

Agoitia-Fonseca, V. G. (2019). La comunidad de mamíferos medianos y grandes en la Reserva de la Biosfera Sierra Gorda y su relación con la heterogeneidad y perturbación ambiental (Tesis de maestría). Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro. Querétaro.

Anaya-Zamora, V., López-González, C. A., & Pineda-López, R. F. (2017). Factores asociados en el conflicto humano-carnívoro en un área natural protegida del centro de México. Ecosistemas y Recursos Agropecuarios, 4, 381–393. https://doi.org/10.19136/era.a4n11.1108

Barragán, F., Moreno, C. E., Escobar, F., Halffter, G., & Navarrete, D. (2011). Negative impacts of human land use on dung beetle functional diversity. Plos One, 6, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0017976

Brandley, M. C., Ota, T. H., Nieto-Montes de Oca, A., Fería-Ortíz, M., Guo, X., & Wang Y. (2012). The phylogenetic systematics of blue-tailed skinks (Plestiodon) and the family Scincidae. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 165, 163–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.2011.00801.x

Bryson, R. W., Linkem, C. W., Dorcas, M. E., Lathrop, A., Jones, J. M., Alvarado-Díaz, J. et al. (2014). Multilocus species delimitation in the Crotalus triseriatus species group (Serpentes: Viperidae: Crotalinae), with the description of two new species. Zootaxa, 3826, 475–496. https://doi.org/10.11646/ZOOTAXA.3826.3.3

Bryson, R. W. Jr., Murphy, R. W., Lathrop, A., & Lazcano-Villareal, D. (2011). Evolutionary drivers of phylogeographical diversity in the highlands of Mexico: a case study of the Crotalus triseriatus species group of montane rattlesnakes. Journal of Biogeography, 38, 697–710. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2010.02431.x

Burbrink, F. T., Bernstein, J. M., Kuhn, A., Gehara, M., & Ruane, S. (2022). Ecological Divergence and the History of Gene Flow in the Nearctic Milksnakes (Lampropeltis triangulum Complex). Systematic Biology, 71, 839–858. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syab093

Carabias-Lillo, J., Provencio, E., de la Maza-Elvira, J., & Ruiz-Corzo, M. I. (1999). Programa de Manejo de la Reserva de la Biosfera Sierra Gorda, México. Mexico D.F.: Instituto Nacional de Ecología.

Cayuela, L., Golicher, D. J., Rey-Benayas, J. M., González-Espinosa, M., & Ramírez-Marcial, N. (2006). Fragmentation, disturbance and tree diversity conservation in tropical montane forests. Journal of Applied Ecology, 43, 1172–1181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2006.01217.x

Conanp (Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas). (2023). Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas, ¿Qué hacemos? Retrieved May 7, 2023 from: http://www.conanp.gob.mx/que_hacemos

Canseco-Márquez, L., Mendoza-Quijano, F., & Gutiérrez-Mayén, M. G. (2004). Análisis de la distribución de la herpetofauna. In I. Luna-Vega, J. J. Morrone, & D. Esparza (Eds.), Biodiversidad de la Sierra Madre Oriental (pp. 417–438).

México, D.F: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad/ Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Clarke, K. R., & Gorley, R. N. (2001). PRIMER v5: user manual/tutorial. -PRIMER-E: Plymouth, UK.

Clarke, K. R., & Warwick, R. M. (1998). A taxonomic distinctness index and its statistical properties. Journal

of Applied Ecology, 35, 523–531. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2664.1998.3540523.x

Colwell, R. K., & Coddington, J. A. (1994). Estimating terrestrial biodiversity through extrapolation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, London (Series B), 345, 101–118. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1994.0091

Cruz-Elizalde, R., Padilla-García, U., Cruz-Pérez, M. C., & Tinoco-Navarro, C. (2016). Herpetofauna del estado de Querétaro. In R. W. Jones, & V. Serrano Cárdenas (Eds.), Historia natural de Querétaro (pp. 300–319). Santiago de Querétaro, Querétaro: Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro.

Cruz-Elizalde, R., Pineda-López, R., Ramírez-Bautista, A., & Berriozábal-Islas, C. (2022). Diversity and composition of anuran communities in transformed landscapes in central Mexico. Community Ecology, 23, 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42974-022-00076-9

Cruz-Elizalde, R., Ramírez-Bautista, A., Hernández-Salinas, U., Berriozábal-Islas, C., & Wilson, L. D. (2019). The herpetofauna of Querétaro. Mexico: species richness, diversity, and conservation status. Zootaxa, 4638, 273–290. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4638.2.7

Cruz-Elizalde, R., Ramírez-Bautista, A., Pineda-López, R., Mata-Silva, V., DeSantis, D. L., García-Padilla, E. et al. (2022). The herpetofauna of Querétaro, Mexico: composition, distribution, and conservation status. Amphibian & Reptile Conservation, 16, 148–192.

Cruz-Elizalde, R., Ramírez-Bautista, A., Wilson, L. D., & Hernández-Salinas, U. (2015). Effectiveness of protected areas in herpetofaunal conservation in Hidalgo, Mexico. Herpetological Journal, 25, 41–48.

Devictor, V., Mouillot, D., Meynard, C., Jiguet, F., Thuiller, W., & Mouquet, N. (2010). Spatial mismatch and congruence between taxonomic, phylogenetic and functional diversity: the need for integrative conservation strategies in a changing world. Ecology Letters, 13, 1030–1040. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01493.x

Díaz de la Vega-Pérez, A. H., Jiménez-Arcos, V. H., Centenero-Alcalá, E., Méndez-de la Cruz, F. R., & Ngo, A. (2019). Diversity and conservation of amphibians and reptiles of a protected and heavily disturbed forest of central Mexico. Zookeys, 830, 111–125. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.830.31490

Dixon, J. R., & Lemos-Espinal, J. A. (2010). Anfibios y reptiles del estado de Querétaro. México D.F.: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad.

Ervin, J. (2003). Protected area assessments in perspective. Bioscience, 53, 819–822. https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568

(2003)053[0819:PAAIP]2.0.CO;2

ESRI (Environmental Systems Research Institute). (2013). ArcGIS Version 10. Redlands, California, USA. Retrieved December 1, 2019 from: https://www.esri.com/es-es/home

Figueroa, F., & Sánchez-Cordero, V. (2008). Effectiveness of natural protected areas to prevent land use and land cover change in Mexico. Biodiversity and Conservation, 17, 3223–3240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-008-9423-3

Fischer, J., & Lindenmayer, D. B. (2007). Landscape modification and habitat fragmentation: a synthesis. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 16, 265-280. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2007.00287.x

Fitzgerald, L. E., Painter, C. W., Reuter, A., & Hoover, C. (2004). Collection, trade & regulation of reptiles and amphibians of the Chihuahuan Desert Ecoregion. Washington D.C.: TRAFFIC North America/ World Wildlife Fund.

Flores-Villela, O., Canseco-Márquez, L., & Ochoa-Ochoa, L. M. (2010). Geographic distribution and conservation of the Mexican central highlands herpetofauna. In L. D. Wilson, J. H. Townsend, & J. D. Johnson (Eds.), Conservation of the Mesoamerican amphibians and reptiles (pp. 303–321). Eagle Mountain, UT: Eagle Mountain Publishing.

Frías-Álvarez, P., Zúñiga-Vega, J. J., & Flores-Villela, O. (2010). A general assessment of the conservation status and decline trends of Mexican amphibians. Biodiversity and Conservation, 19, 3699–3742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-010-9923-9

Frost, D. R. (2023). Amphibian species of the World: an online reference. Versions 6.1. Retrieved April 13, 2023 from: http://

www.research.amnh.org/herpetology/amphibia/index.html

García-Bañuelos, P., Rovito, S. M., & Pineda, E. (2019). Representation of threatened biodiversity in protected areas and identification of complementary areas for their conservation: Plethodontid Salamanders in Mexico. Tropical Conservation Science, 12, 1940082919834156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940082919834156

García-Castillo, M. G., Rovito, S. M., Wake, D. B., & Parra-Olea, G. (2017). A new terrestrial species of Chiropterotriton (Caudata: Plethodontidae) from central Mexico. Zootaxa, 4363, 489–505. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4363.4.2

García-Castillo, M. G., Soto-Pozos, A. F., Aguilar-López, J. L., Pineda, E., & Parra-Olea, G. (2018). Two new species of Chiropterotriton (Caudata: Plethodontidae) from central Veracruz, Mexico. Amphibian & Reptile Conservation, 12, 37–54.

García-Padilla, E., DeSantis, D. L., Rocha, A., Mata-Silva, V., Johnson, J. D., Fucksco, L. A. et al. (2021). Mesoamerican salamanders (Amphibia: Caudata) as a conservation focal group. Biología y Sociedad, 7, 73–87.

García-Sotelo, U. A., García-Vázquez, U. O., & Espinosa, D. (2021). Historical biogeography of the genus Rhadinaea (Squamata: Dipsadinae). Ecology and Evolution, 11, 12413–12428. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.7988

GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility). (2019). Anfibios y reptiles del estado de Querétaro. Nieto-Montes de Oca A., & Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad. Retrieved December 02, 2019 from: https://doi.org/10.15468/xwpedz

Gillingwater, S., & Patrikeev, M. (2004). Herpetological records from Reserva de la Biosfera Sierra Gorda (Querétaro, México). Toronto: Institute for the Conservation of World Biodiversity.

Grünwald, C. I., Ahumada-Carrillo, I. T., Grünwald, A. J., Montaño-Ruvalcaba, C. E., & García-Vázquez U. O. (2021). A new species of Geophis (Dipsadidae) from Veracruz, Mexico, with comments on the validity of related taxa. Amphibian & Reptile Conservation, 15, 289–310.

Gutiérrez-Yurrita, P. J., & Morales-Ortiz, J. A. (2004). Síntesis y perspectivas del estatus ecológico de los peces del estado de Querétaro (Centro de México). In M. A. Lozano-Vilano, & A. J. Contreras-Balderas (Comps.), Homenaje al Doctor Andrés Reséndez Molia. Un ictiólogo mexicano (pp. 217–234). Monterrey: Dirección de Publicaciones, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León.

Hallas, J. M., Parchman, T. L., & Feldman, C. R. (2022). Phylogenomic analyses resolve relationships among garter snakes (Thamnophis: Natricinae: Colubridae) and elucidate biogeographic history and morphological evolution. Molecular Phylogenetic and Evolution, 167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2021.107374

Íñiguez-Dávalos, L. I., Jiménez-Sierra, C. L., Sosa-Ramírez, J., & Ortega-Rubio, A. (2014). Categorías de las áreas naturales protegidas en México y una propuesta para la evaluación de su efectividad. Investigación y Ciencia de la Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes, 60, 65–70.

IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature). (2023). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2022-2. Retrieved March 19, 2023 from: http://www.iucnredlist.org

Johnson, J. D., Wilson, L. D., Mata-Silva, V., García-Padilla, E., & DeSantis, D. L. (2017). The endemic herpetofauna of Mexico: Organisms of global significance in severe peril. Mesoamerican Herpetology, 4, 544–620.

Jones, R. W., & Serrano-Cárdenas, V. (2016). Historia Natural de Querétaro. Querétaro: Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro.

Lara-Tufiño, D., Hernández-Austria, R., Wilson, L. D., Ramírez-Bautista, A., & Berriozabal-Islas, C. (2014). New state record for the snake Amastridium sapperi (Squamata: Dipsadidae) from Hidalgo, Mexico. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 85, 654–657. https://doi.org/10.7550/rmb.40543

Leaché, A. D., Banbury, B. L., Linkem, C. W., & Nieto-Montes de Oca, A. (2016). Phylogenomics of a rapid radiation: is chromosomal evolution linked to increased diversification in North American spiny lizards (Genus Sceloporus)? BMC Evolutionary Biology, 16, 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-016-0628-x

Lemos-Espinal, J. A., & Smith, G. R. (2020). A conservation checklist of the amphibians and reptiles of the State of Mexico, Mexico with comparisons with adjoining states. Zookeys, 953, 137–159. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.953.50881

Lemos-Espinal, J. A., Smith, G. R., & Woolrich-Piña, G. A. (2018). Amphibians and reptiles of the state of San Luis Potosí, Mexico, with comparisons with adjoining states. Zookeys, 753, 83–106. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.753.21094

Leyte-Manrique, A., Balderas-Valdivia, C. J., Cedeña-Rico, S., & Ballesteros-Barrera, C. (2022). Los agroecosistemas como refugios de la biodiversidad: el caso de los anfibios y reptiles. Biología y Sociedad, 5, 37–47. https://doi.org/10.29105/bys5.9-4

Leyte-Manrique, A., Mata-Silva, V., Báez-Montes, O., Fucsko, L. A., DeSantis, D. L., García-Padilla, E. et al. (2022). The herpetofauna of Guanajuato, Mexico: composition, distribution, and conservation status. Amphibian & Reptile Conservation, 16, 133–180.

Martínez-Morales, M. A. (2007). Avifauna del bosque mesófilo de montaña del noreste de Hidalgo, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 78, 149–162.

Mercado, N., & del Val, E. (2021). Manejo y conservación de fauna en ambientes antropizados. Querétaro, Mexico: REFAMA-UAQ.

Mittermeier, R. A., Myers, N., Thomsen, J. B., da Fonseca, G. A. B., & Olivieri, S. (1998). Biodiversity hotspots and major tropical wilderness areas: approaches to setting conservation priorities. Conservation Biology, 12, 516–520. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.1998.012003516.x

Moreno, C. E., Castillo-Campos, G., & Verdú, J. R. (2009). Taxonomic distinctiveness as complementary information to assess plant species diversity in secondary vegetation and primary tropical deciduous forest. Journal of Vegetation Science, 20, 935–943. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1654-1103.2009.01094.x

Morrone, J. J. (2005). Hacia una síntesis biogeográfica de México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 76, 207–252. https://doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2005.002.303

Nieto-Montes de Oca, A., Barley, A. J., Meza-Lázaro, R. N., García-Vázquez, U. O., Zamora-Abrego, J. G., Thomson, R. C. et al. (2017). Phylogenomics and species delimitation in the knob-scaled lizards of the genus Xenosaurus (Squamata: Xenosauridae) using ddRADseq data reveal a substantial underestimation of diversity. Molecular Phylogenetic and Evolution, 106, 241–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2016.09.001

Nori, J., Lemes, P., Urbina-Cardona, N., Baldo, D., Lescano, J., & Loyola, R. (2015). Amphibian conservation, land-use changes and protected areas: a global overview. Biological Conservation, 191, 367–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2015.07.028

Ochoa-Ochoa, L. M., Campbell, J. A., & Flores-Villela, O. (2014). Richness and endemism of the Mexican herpetofauna, a matter of spatial scales? Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 111, 305–316. https://doi.org/10.1111/bij.12201