Mildred Fabiola Corona-Figueroa a, John Alexander Giraldo-Mueses b,

José Rogelio Cedeño-Vázquez a, *, Delma Nataly Castelblanco-Martínez c, d, Carlos Alberto Niño-Torres c, Pablo M. Beutelspacher-García e, Silvana Marisa Ibarra-Madrigal f, Jonathan Pérez-Flores g

a El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Departamento de Sistemática y Ecología Acuática, Avenida Centenario Km 5.5, 77014 Chetumal, Quintana Roo, Mexico

b Universidad del Tolima, Barrio Santa Helena Parte Alta, 730006299 Tolima, Ibagué, Colombia

c Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Quintana Roo, División en Desarrollo Sustentable, Blvd. Bahía s/n Esq. Ignacio Comonfort, Col. del Bosque, 77019 Chetumal, Quintana Roo, Mexico

d Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, Cátedras Jóvenes Investigadores, Av. Insurgentes Sur 1582, Col Crédito Constructor, Alcaldía Benito Juárez, 03940 Ciudad de México, Mexico

e Independent Researcher, Martinica 342, Fracc. Caribe, 77086 Chetumal, Quintana Roo, Mexico

f Geo Alternativa A.C., Quito Núm. 1260, Col. Providencia, 33460 Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico

g El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Departamento de Observación y Estudio de la Tierra, la Atmósfera y el Océano, Avenida Centenario Km 5.5, 77014 Chetumal, Quintana Roo, Mexico

*Corresponding author: rcedenov@ecosur.mx (J.R. Cedeño)

Received: 2 December 2020; accepted: 30 June 2021

Abstract

The Neotropical otter Lontra longicaudis is one of the least studied mammals of the Yucatán Peninsula and its presence in some water bodies of this region is questionable. Laguna Bacalar is the largest freshwater body located in the Yucatán Peninsula and faces several conservation problems due to its high potential for tourism development. We confirmed the presence of L. longicaudis in Laguna Bacalar by conducting interviews with residents, and the search for direct (sightings) and indirect (e.g., footprints) evidence of the species in 2013. We also include recent direct and indirect evidence (2019-2020). We classified the records into levels of certainty, according to the type of evidence (photographs, videos). We obtained 9 records of Neotropical otter through interviews (level 3), 3 sightings and 4 footprints (level 1), and 4 sightings (3 of these with level 2 and 1 with level 3 of certainty). It is necessary to increase the research effort to determine the conservation status and distribution of the Neotropical otter in the lagoon. We recommend making efforts in terms of socialization and education to facilitate the conservation of the Neotropical otters and their habitat in Laguna Bacalar.

Keywords: Mustelidae; Yucatán Peninsula; Freshwater habitat; Aquatic mammal

Keywords: Mustelidae; Yucatán Peninsula; Freshwater habitat; Aquatic mammal

© 2022 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license

Confirmación de la presencia de la nutria neotropical, Lontra longicaudis, en la laguna de Bacalar, Quintana Roo, México

Resumen

La nutria neotropical Lontra longicaudis es uno de los mamíferos menos estudiados en la península de Yucatán y su presencia en algunos cuerpos de agua de esta región es cuestionable. La laguna de Bacalar es el mayor cuerpo de agua dulce de la península de Yucatán y enfrenta varios problemas de conservación debido a su alto potencial de desarrollo turístico. Confirmamos la presencia de L. longicaudis en la laguna de Bacalar mediante entrevistas con los residentes locales y la búsqueda de evidencias directas (avistamientos) e indirectas (p. ej. huellas) de presencia de la especie en 2013. Incluimos observaciones directas recientes (2019-2020). Clasificamos la información por niveles de certeza, según el tipo de evidencia que la respalda (fotografías, videos). Obtuvimos 9 registros de nutria neotropical a través de entrevistas (nivel 3); 3 avistamientos y 4 huellas (nivel 1), y 4 avistamientos (3 con nivel 2 y 1 con nivel 3 de certeza). Es necesario incrementar los esfuerzos de investigación para determinar el estado de conservación y la distribución de la nutria neotropical en la laguna. Recomendamos realizar esfuerzos en cuanto a la socialización y a la educación para facilitar la conservación de esta especie y su hábitat en la laguna de Bacalar.

Palabras clave: Mustelidae; Península de Yucatán; Hábitat dulceacuícola; Mamífero acuático

© 2022 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. Este es un artículo Open Access bajo la licencia CC BY-NC-ND

Introduction

The Neotropical otter, Lontra longicaudis (Olfers, 1818), is an elusive mustelid, with a wide distribution from northwestern and northeastern Mexico to Uruguay, Paraguay, and northern Argentina (Larivière, 1999). This species inhabits rivers, streams with strong currents, and lagoons located between 0 to 3,000 m in altitude (Larivière, 1999; Rheingantz et al., 2021; Trujillo & Arcila, 2006). In Mexico, L. longicaudis occurs in the southern area of the state of Tamaulipas and the slope of the Gulf of Mexico, and in the northern area of Sonora, Chihuahua, and Durango, and the continental slopes of the Sierra Madre Occidental and Sierra Madre Oriental, southward to the border with Guatemala (Aranda-Sánchez, 2015; Gallo-Reynoso, 1997; Gallo-Reynoso & Meiners, 2018).

In Mexico, information about distribution, population status, ecology, and conservation aspects of L. longicaudis has been obtained from systematic studies mainly from the northwestern (Cruz-García et al., 2017; Gallo-Reynoso, 1997; Gallo-Reynoso et al., 2008; García-Silva et al., 2021; Rangel-Aguilar & Gallo-Reynoso, 2013), western (Brito-Ríos, 2017; Casariego, 2013; Espinoza-Medinilla et al., 1998; Gallo-Reynoso, 1989), central (Guerrero-Flores et al., 2013) and Gulf of Mexico (Macías-Sánchez, 2003; Santiago-Plata et al., 2013) regions. In Quintana Roo, this species has been reported for the Reserva de la Biosfera Sian Ka’an, Laguna Guerrero, Laguna Chile Verde, the north and northeastern portion of Chetumal Bay, and in the Río Hondo along the border with Belize (Calmé & Sanvicente, 2009; Escobedo-Cabrera et al., 2002, 2009; Gallo-Reynoso, 1997; Morales-Vela & Olivera-Gómez, 1991, 1994; Morales-Vela et al., 2011; Orozco-Meyer, 1998). However, efforts to monitor this species in Quintana Roo have been scarce.

Neotropical otters are top predators in the trophic food chain of riverine systems, feeding predominantly upon fishes, but also consuming other groups of organisms (Santiago-Plata et al., 2013; Gallo-Reynoso et al., 2008). The communal latrines of this species represent a food resource for vertebrate and invertebrate communities, therefore playing an important role in the trophic chain (Laurentino et al., 2019). Populations of L. longicaudis have been extirpated in several areas of its historical distribution due to the fur trade, their capture and use as pets, and conflicts with fishermen (Gallo-Reynoso, 1989; Santiago-Plata et al., 2013). Nowadays, L. longicaudis is listed as Near Threatened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (Rheingantz et al., 2021); as Threatened in the Official Mexican Norm 059 (NOM-059- ECOL-2010) (Semarnat, 2010), and included in the Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES, 2019).

The Laguna Bacalar is located in the southern part of Quintana Roo, between the municipalities of Bacalar and Othón P. Blanco (Gómez-Pech et al., 2018). This lagoon and its surroundings have an enormous potential for tourism due to the attractive landscape and other environmental attributes (Semarnat, 2015). In 2018, around 90,000 tourists visited Bacalar, and tourism is expected to increase in the near future, which has serious implications on the transformation of land use in the human settlements near the lagoon (Gómez-Pech et al., 2018; Yanez-Montalvo et al., 2020).

Several governmental policies protect the Laguna Bacalar such as the establishment of defined environmental management units in order to maintain ecosystem connectivity and the conservation of biological diversity (Semarnat, 2015). Additionally, several lagoons interconnected with the Laguna Bacalar (e.g., Chile Verde) are included within the Natural Protected Area Santuario del Manatí-Bahía de Chetumal (DOF, 2008). Nevertheless, productive activities with low environmental impact are allowed in Laguna Bacalar, with restrictions that guarantee conservation and promote a minimum change in land use (Semarnat, 2015). Until now, information regarding L. longicaudis along the shoreline of Laguna Bacalar consisted in anecdotes told by people living in the surrounding area of the lagoon (Morales-Vela & Olivera-Gómez, 1991). Here, we compiled evidence that confirms the contemporary occurrence of L. longicaudis in this intense use touristic lagoon.

Materials and methods

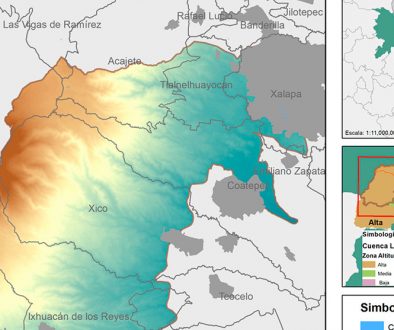

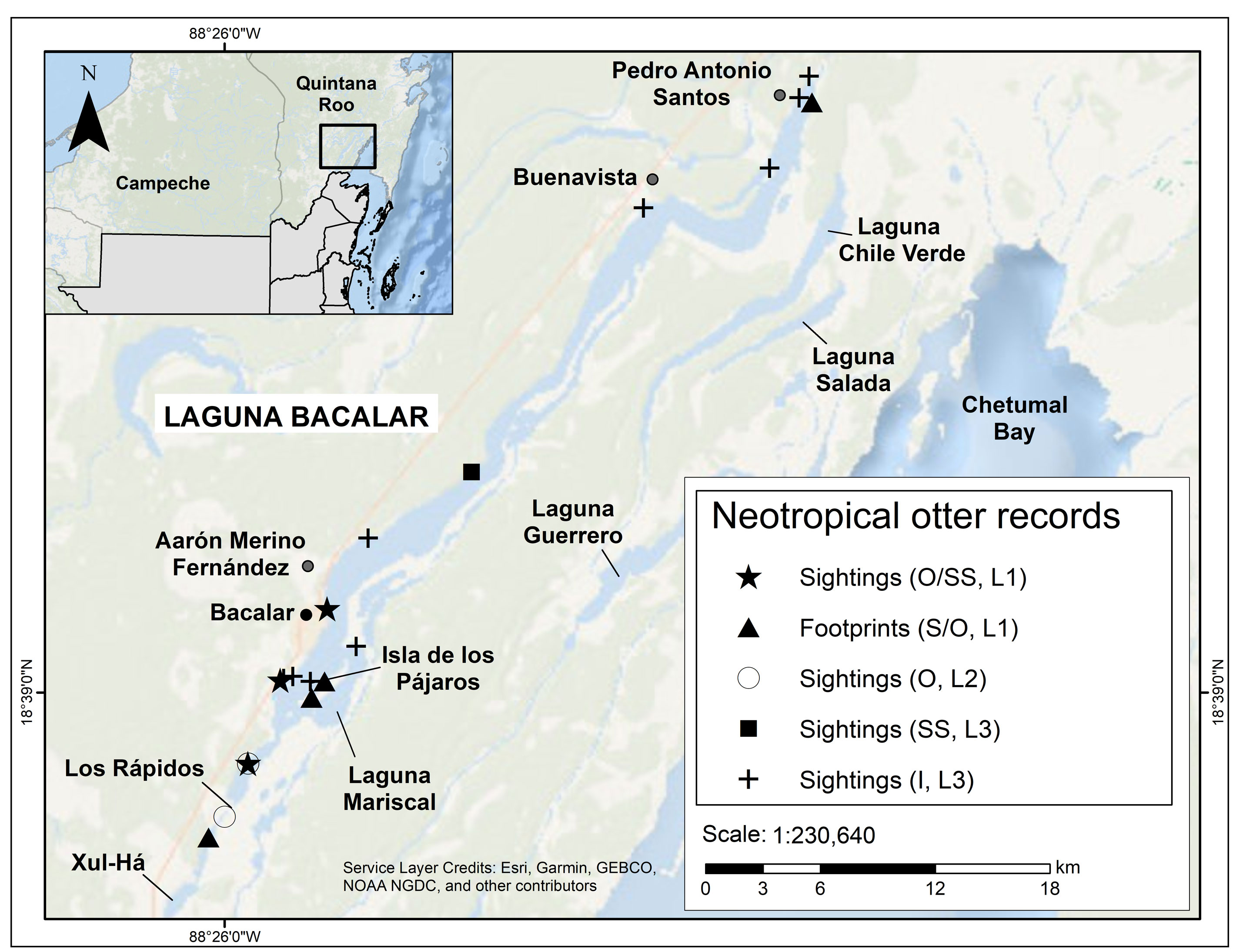

The study area corresponds to the shoreline of Laguna Bacalar, which encompasses the lagoon itself, the surrounding wetlands (from 18º56’49.35” N, 88º08’58.97” W, and 18º31’37.27” N, 88º28’06.80” W), and the human settlements next to the lagoon (Xul-Ha, Bacalar, Aarón Merino Fernández, Buenavista, and Pedro Antonio Santos) (Fig. 1). The Laguna Bacalar has an area of 9,572.74 ha, and consists of 43% of surface waters and 49% of mangrove forest (Rhizophora mangle, Conocarpus erectus and Laguncularia racemosa); the remaining 8% corresponds to vegetation of tular (Typha sp.), secondary shrub and tropical deciduous forest, and cultivated pastures for cattle (Semarnat, 2015).

The origin of the Laguna Bacalar is not completely karstic, its physiognomy is the product of the tectonic dynamic that occurred at the Upper Miocene age along the lagoon and the Río Hondo (Ceballos-Martínez, 2002). This lagoon has a length of 54 km in a straight line from the southern to the northern orientation and a maximum width of 2 km; it communicates superficially with the Río Hondo through the Chac stream (Ceballos-Martínez, 2002), and through several shallow streams with the Laguna Chile Verde, which flows into Laguna Guerrero (Fig. 1) (Morales-Vela & Olivera-Gómez, 1991). The region is characterized by a subhumid warm climate, with an average annual temperature of 26.8 °C (range, 16.15 °C – 34.9 °C) and an accumulated average annual precipitation of 1,040.8 mm (range, 12 mm – 2,243.6 mm), which intensifies between June and September (SMN & Conagua, 2020). The municipality of Bacalar has a population of 41,754 inhabitants, being the town of Bacalar the main human settlement with 12,527 inhabitants (INEGI, 2020).

During April to August 2013, we conducted 30 semi-structured interviews with key inhabitants such as boatmen, fishermen and hosts from Xul-Há, Bacalar, Buena Vista, and Pedro Antonio Santos to gather information on the presence of L. longicaudis in the lagoon. The choice of the interviewees depended on the characteristics of each town visited in terms of people’s occupation and proximity of the residences to the lagoon. In parallel, we conducted 16 field trips to the sites reported by the interviewees as potential areas of the Neotropical otter presence. The surveys consisted of navigations in kayak along the shore of the lagoon in search of evidences of L. longicaudis presence, such as shelters, latrines, feces, or footprints (Orozco-Meyer, 1998). When possible, we walked on ground to examine approximately 1 m of the lagoon edge, depending on the site characteristics. When footprints were found, we measured their length and width in situ and used field guides to verify the identification (Aranda, 2000; Reid, 1997). These field trips were carried out from May to August 2013, between 6:30 a.m. to 3:40 p.m.

To include recent data on the presence of L. longicaudis in the lagoon, we searched for published literature obtained from Google Scholar and information published between 2014-2020 in local newspapers, social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter), and virtual databases (e.g., iNaturalist, GBIF) as secondary sources of information. All data were compiled in a database accompanied by the date, time, geographic coordinates, and the name of the observer, and included reliable records of opportunistic observations obtained in March, July, and September 2019.

We classified the records into indirect signs of the presence of Neotropical otter (e.g., footprints, feces, latrines, or shelters), and direct sightings (e.g., individuals of the Neotropical otter). We also assigned a level of certainty to each obtained record, as follows: level 1, indirect and direct records consisting in confirmed sightings with a high degree of certainty and corroborated with evidence (e.g., photographs, videos). We also included observations made by villagers with some supporting evidence (photographs, videos). Level 2, indirect and direct records made by coauthors, but without evidence (photographs or videos). Level 3, indirect and direct records without evidence or detailed descriptions obtained through interviews or observations made by villagers.

Results

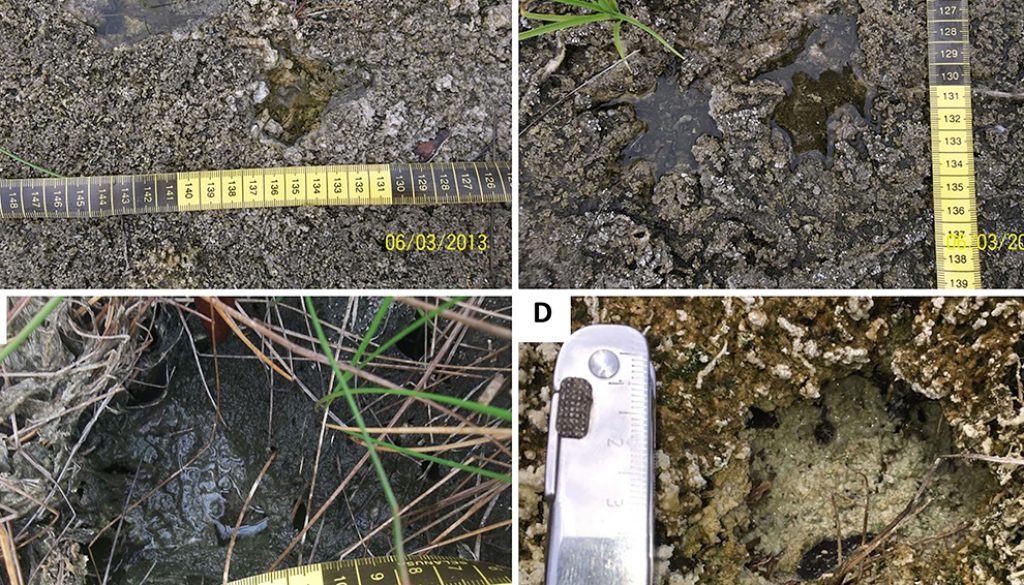

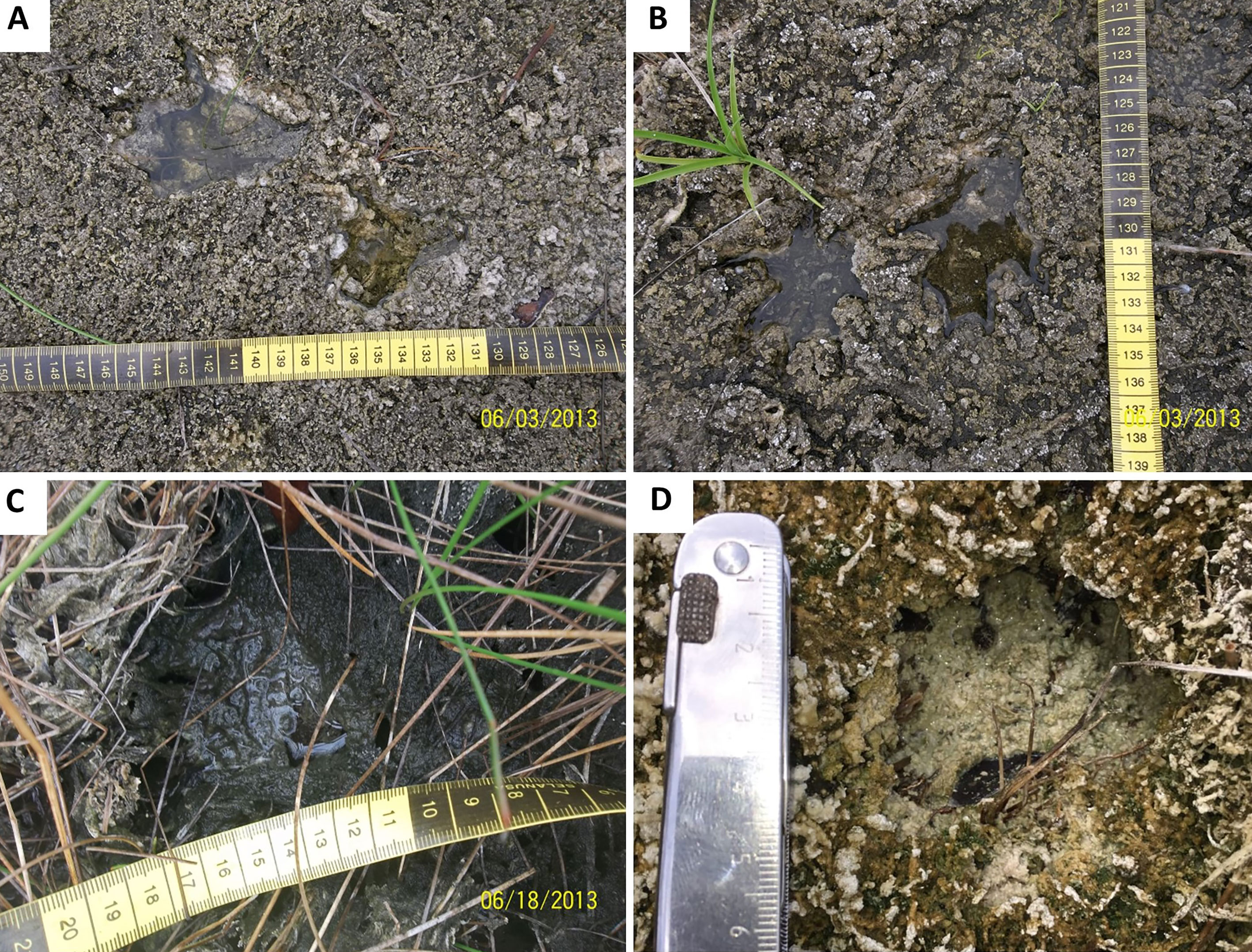

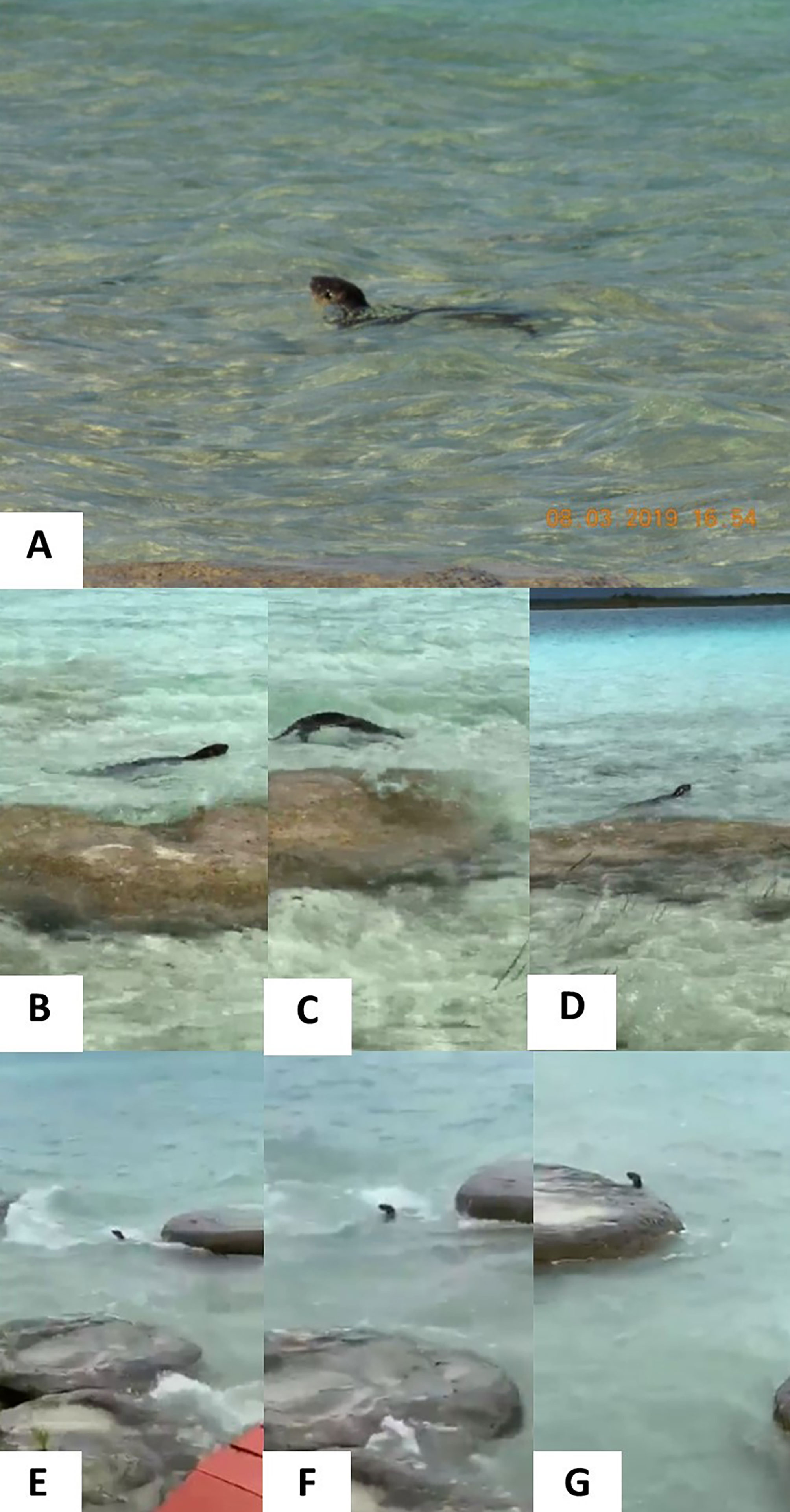

We obtained 9 records of Lontra longicaudis sightings in different areas of the Laguna Bacalar through interviews (level 3 degree of certainty; Fig. 1). Additionally, between 2013 and 2020, we compiled 11 records of the species during surveys, opportunistically or by review of secondary sources, consisted of indirect (footprints, n = 4; Fig. 2) and direct (sightings, n = 7; Fig. 3) records (Table 1). Indirect and direct records with evidence (photographs, videos) correspond to level 1 degree of certainty (Table 1). Also, we recorded 4 sightings, 3 with level 2 degree of certainty and made by a villager with level 3 degree of certainty (Table 1). Detailed results are described below.

Interviews. We conducted 30 interviews to key people between 15 and 85 years old, but the majority (37%) were between 35-50 years old. The main activities of the interviewees in Bacalar town were workers of the hotel sector (37.7%) and boat captains (20%), while in Buena Vista and Pedro Antonio Santos villages were mostly farmers (40%). Of the total sample, only 16 interviewees (53.3%) indicated sightings of L. longicaudis in different environments such as in the water, mangrove forest, docks, and beaches at 4 sites: Bacalar town, ‘Los Rápidos’, Pedro Antonio Santos, and the Laguna Mariscal (Fig. 1). Additionally, interviewees indicated that they have seen L. longicaudis in the study area at least once or twice in their lives (average age = 36 years old, range = 15-85). Among the people who have had direct sightings of Neotropical otters, 36.7% have seen solitary individuals, while 6.7% have seen pairs and 10% have seen groups larger than 4 individuals.

Surveys. The systematic search for L. longicaudis conducted in 2013 covered 51.2 km of shoreline, channels, and wetlands, with a total sampling effort of 114 h (7 h daily). We found 3 footprints of L. longicaudis, 2 of them close to each other in a small channel located on the eastern edge of the lagoon, on Isla de los Pájaros (Fig. 2A, B). These footprints indicated that the individual was running and measured 6-8 cm long and 5-6 cm wide. A third footprint was found in the Pedro Antonio Santos village and measured 7 cm long by 6 cm wide (Fig. 2C). Additional footprints were found but they were very old or not clear, and we decided not to include them. None of these individuals were observed, or their feces found during these surveys.

Opportunistic records. On 29th July 2020, another footprint was recorded by Pablo M. Beutelspacher-García (PMB-G) in the southern part of the lagoon near Xul Há (Fig. 2D). This footprint was 4 cm wide, and the plantar surface was more evident as a Neotropical otter. All following sightings of L. longicaudis were obtained opportunistically and recorded during daylight hours at a short distance from the west shore of the lagoon. Sightings 1 (Table 1; Fig. 3A): on 8th March 2019 an adult L. longicaudis was observed swimming on the southwest side of the lagoon by Pablo M. Beutelspacher-García (PMB-G) at 16.54 h in an area of mangroves and aquatic grasses. Days later (March 13th and 14th, 2019) and around the same time, PMB-G observed an adult Neotropical otter in the same place again. We do not have evidence to indicate whether it was the same or a different individual; however, we consider both sightings as different records (Table 1: sighting 2 and 3). Sighting 4: this sighting was made on September 1st 2019 by Silvana Marisa Ibarra-Madrigal (SMI-M) corresponding to an adult L. longicaudis observed in Los Rápidos, an area where the lagoon narrows about 5 m, with an average depth of 4 m, increasing the water flow (1.03 to 2.06 m/s) compared to the rest of the lagoon.

Secondary sources. The following records correspond to opportunistic sightings. Sighting 5: an adult of L. longicaudis was sighted by a villager in 2010, who contacted Jonathan Pérez-Flores (JP-F); however, no details of the observation were obtained. Sighting 6: on 31st August 2019 a villager recorded a 46-second video of an adult L. longicaudis in the southern end of the lagoon. The video showed the individual swimming, breathing, and moving southward (Fig. 3B-D). José Rogelio Cedeño-Vázquez (JRC-V) contacted the villager to retrieve the information and video about this sighting. Sighting 7: on 12th April 2020 a 55-second video of an adult L. longicaudis was recorded near the shoreline of Laguna Bacalar by a local villager. The individual was swimming, breathing, and moving northward (Fig. 3E-G). The video was broadcast on social media and a journalist contacted Delma Nataly Castelblanco-Martínez (DNC-M) to write a note about the sighting in a local newspaper.

Discussion

We report the presence of the Neotropical otter in the Laguna Bacalar through photographs of an individual and 4 footprints, complemented with secondary information obtained through interviews with local inhabitants and videos recorded by villagers.

Although the raccoon (Procyon lotor), and other mustelids such as the greater grison (Galictis vittata) and the tayra (Eira barbara) have been recorded in the area (Lorenzo et al., 2008; Pozo de la Tijera, 1997; Pozo de la Tijera et al., 1991), the possibility of confusing the sets of footprints of these species with L. longicaudis were demoted based on the measurements obtained in the field, which were consistent with the identification guides (Aranda-Sánchez, 2015; Gallo-Reynoso & Casariego, 2005; Reid, 1997). The Neotropical otter’s front and hind feet have very short and thick claws whereas the hind claws are relatively longer. In deep footprints, it is possible to distinguish the interdigital membrane on both front and hind feet (e.g., Fig. 2A, B). In contrast, footprints of the greater grison, tayra, and raccoon have short and thin claws (Aranda-Sánchez, 2015); in addition, raccoon tracks present elongated, rounded and long toes without an interdigital membrane.

The videos and photographic records are evidence of individuals with the distinctive external characteristics of L. longicaudis: a medium-size mammal, dark grayish-brown pelage, with a long tail, and a relative small and flat head (Larivière, 1999). Additionally, greater grison, tayras, and racoons are predominantly terrestrial (Chávez-Tovar, 2005a, b; Valenzuela-Galván, 2005). The sightings described in this study consisted of swimming individuals of L. longicaudis, which is a common behavior on their habitat (Kruuk, 2006). The reported footprints were also found close to the aquatic habitat of L. longicaudis (Gallo-Reynoso & Casariego, 2005; Kruuk, 2006; Muãnis & Oliveira, 2011).

We confirmed the presence of L. longicaudis in all the locations on the shoreline of Laguna Bacalar that were previously indicated by interviewees, except for the Laguna Mariscal. Previous authors reported the presence of L. longicaudis in nearby places, such as Río Hondo, Laguna Guerrero and Laguna Chile Verde (Calmé y Sanvicente, 2009), indicating the possibility of dispersion between water bodies. The Neotropical otter can move between streams that converge in different rivers, covering not only the course of water bodies, but also terrestrial environments (Gallo-Reynoso, 1989). The findings presented here indicate that L. longicaudis occurs in the western area of the Laguna Bacalar, which is connected to other karstic freshwater bodies, such as Laguna Milagros, Río Hondo (through the Chac stream), and Mariscal and Chile Verde brackish lagoons. Our observations suggest that L. longicaudis could benefit from this complex natural corridor, based on hydrological connections as means of dispersal and probable foraging behavior (Hernández-Arana et al., 2015).

The Neotropical otter does not strictly mark its terrestrial boundaries, instead, it uses scent marks, such as spraints, mucus, urine and feces for intraspecific communication and for habitat selection (Michalski et al., 2021; Roberts et al., 2016). Neotropical otters have high site fidelity, and their home range varies from 2 to 7 km in length (Gallo-Reynoso, 1989; Roberts et al., 2016). In addition, sex, food availability and the reproductive season generally determine the size of the otters home range (Blundell et al., 2000; Gallo-Reynoso, 1989; Kruuk, 2006). In this study, we collected direct and indirect records of Neotropical otters confirming its presence, but questions about how this species uses the habitat available in Laguna Bacalar and surroundings remain unresolved.

Previous research on the diet of L. longicaudis indicates preference for fish; nevertheless, mollusks, insects, crustaceans, amphibians, reptiles, birds and small mammals are also consumed (Gallo-Reynoso, 1997; Juárez-Sánchez et al., 2019; Platt & Rainwater, 2011; Santiago-Plata et al., 2013). Since Laguna Bacalar is an important habitat for several freshwater fish species (Arce-Ibarra, 2011; Gamboa-Pérez, 1991; Valdez-Moreno et al., 2019), there is a considerable availability and diversity of prey for the Neotropical otter. Other important potential prey for the species such as insects (e.g., Coleoptera; Morón-Ríos, 2011), amphibians (Bufonidae, Hylidae) and reptiles (Dermatemydidae, Emydidae, Geoemydidae, Kinosternidae, Iguanidae, Colubridae) (Pozo de la Tijera et al., 1991; Pablo M. Beutelspacher-García pers. obs.) are also part of the native fauna of the Laguna Bacalar ecosystem. The knowledge about feeding habitats of L. longicaudis in the area, including diet composition, prey preference, and seasonal variability is absent. Therefore, future studies on the Neotropical otter diet in this lagoon conducted in different climatic seasons would be informative to better understand the ecological role of the species in this region.

Neotropical otters can be found in areas with certain levels of anthropogenic disturbance, as long as there are food availability and places for refuge, and extensive aquatic networks (Gallo-Reynoso, 1997; Gallo-Reynoso et al., 2019; Larivière, 1999). However, the effect of environmental degradation needs to be further investigated at population level since it can affect refuge availability and space use patterns (Pardini & Trajano, 1999; Rheingantz et al., 2017). Although we did not measure environmental and habitat quality variables in the lagoon during this study, previous studies have indicated an incipient contamination of Laguna Bacalar and the Yucatán Peninsula waters due to agricultural practices, local wastewater contamination, and intensive tourism (Aranda-Cirerol et al., 2011; Tobón-Velázquez et al., 2019; Yanez-Montalvo et al., 2020). Considering the increasingly growing tourism and economic development of the Laguna Bacalar (Gómez-Pech et al., 2018; Ibarra-Madrigal et al., 2020), we suggest developing future studies on habitat quality to describe the human-related factors that could affect the lagoon as a suitable habitat for this species.

It is interesting to note that most of the opportunistic encounters with Neotropical otters occurred recently (2019-2020), suggesting an increase in population or improvement in conservation status. In this sense, a long-term monitoring program is needed to investigate changes in species abundance and distribution. Such studies can indicate connectivity between water bodies (Hernández-Arana et al., 2015), which could contribute to the proposal and establishment of effective strategies for the conservation of this species and habitat management, also expanding the polygon of the Natural Protected Area Santuario del Manatí-Bahía de Chetumal towards the northern of Laguna Bacalar could be considered in the future. Since the Neotropical otter is an elusive semi-aquatic mammal, we recommend using new methodological approaches to estimate the presence and relative abundance of the species such as camera traps (Barocas et al., 2016; Gallo-Reynoso et al., 2019; Wagnon & Serfass, 2016), environmental DNA (eDNA) (Beng & Corlett, 2020; Ma et al., 2016; Padgett-Stewart et al., 2016), and drones (Bushaw et al., 2019; Christie et al., 2016).

Finally, it is critical to know the conservation status of the Neotropical otter at the local level to implement future awareness campaigns and sensitize stakeholders to work towards the conservation of this species. Our study benefited from information obtained by citizens and journalists, therefore, a citizen science project addressing L. longicaudis status in Laguna Bacalar is essential to both monitor the species and involve local inhabitants in its protection.

Table 1

Neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis) records along the shoreline of Laguna Bacalar in 2010, 2013, and between March 2019 and April 2020. See the text for more details about certainty level criteria.

| No. | Date and time | Type of record | Method | Type of evidence | Certainty level |

| 1 | 03 Jun 2013, 17.30 h | Indirect (footprints) | Survey | Photograph (Fig. 2A) | 1 |

| 2 | 03 Jun 2013, 13.20 h | Indirect (footprints) | Survey | Photograph (Fig. 2B) | 1 |

| 3 | 18 Jun 2013, 13.20 h | Indirect (footprints) | Survey | Photograph (Fig. 2C) | 1 |

| 4 | 29 Jul 2019, 09.45 h | Indirect (footprints) | Opportunistic | Photograph (Fig. 2D) | 1 |

| 5 | 08 Mar 2019, 16.54 h | Direct (sighting 1) | Opportunistic | Photograph (Fig. 3A) | 1 |

| 6 | 13 Mar 2019, 16.08 h | Direct (sighting 2) | Opportunistic | None | 2 |

| 7 | 14 Mar 2019, 15.15 h | Direct (sighting 3) | Opportunistic | None | 2 |

| 8 | 01 Sep 2019, undefined | Direct (sighting 4) | Opportunistic | None | 2 |

| 9 | ? ? 2010, undefined | Direct (sighting 5) * | Secondary sources | None | 3 |

| 10 | 31 Aug 2019, afternoon | Direct (sighting 6) † | Secondary sources | Video (Fig. 3B-D) | 1 |

| 11 | 12 Apr 2020, afternoon | Direct (sighting 7) ‡ | Secondary sources | Video (Fig. 3E-G) | 1 |

Acknowledgments

This work was partially product of the PhD of Mildred Fabiola Corona Figueroa (MFC-F), who received a grant from Conacyt. To the Society of Marine Mammalogy for awarding a Small Grant in Aid of Research to Delma Nataly Castelblanco-Martínez (DNC-M) in 2013, and to the Ecology and Environment Direction of the Municipality of Bacalar, for the logistical support during the field surveys conducted in 2013. To R. E. Salazar Cruz, a villager of Bacalar, for sharing the video of the otter observed on August 31, 2019. We thank Marcelo Lopes Rheingantz and Juan Carlos Botello for helping in footprint identification. To journalists and correspondents of local newspapers for providing us the video of the otter observed in April 2020. To the anonymous reviewers for their comments, which were valuable inputs to the manuscript. Finally, we thank Brianna Jacobson and Steven G. Platt for the English review of this manuscript.

References

Aranda, M. (2000). Huellas y otros rastros de los mamíferos grandes y medianos de México. México D.F.: Instituto de Ecología, A. C./ Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad.

Aranda-Sánchez, J. M. (2015). Manual para el rastreo de mamíferos silvestres de México. México D.F.: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad.

Aranda-Cirerol, N., Comín, F. A., & Herrera-Silveira, J. (2011). Nitrogen and phosphorus budgets for the Yucatán littoral: an approach for groundwater management. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 172, 493–505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-010-1349-z

Arce-Ibarra, A. M. (2011). Pesca continental. In C. Pozo, N. Armijo, & S. Calmé (Eds.), Riqueza biológica de Quintana Roo. Un análisis para su conservación. Tomo I. (pp. 194–196). México D.F.: ECOSUR/ Conabio/ Gobierno del Estado de Quintana Roo/ PPD.

Barocas, A., Golden, H. N., Harrington, M. W., McDonald, D. B., & Ben-David, M. (2016). Coastal latrine sites as social information hubs and drivers of river otter fission-fusion dynamics. Animal Behaviour, 120, 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2016.07.016

Beng, K. C., & Corlett, R. T. (2020). Applications of environmental DNA (eDNA) in ecology and conservation: opportunities, challenges and prospects. Biodiversity and Conservation, 29, 2089–2121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-020-01980-0

Blundell, G. M., Bowyer, R. T., Ben-David, M., Dean, T. A., & Jewett, S. C. (2000). Effects of food resources on spacing behavior of river otters: does forage abundance control home-range size? In J. H. Eiler, D. J. Alcorn, & M. R. Neuman (Eds.), Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Symposium on Biotelemetry (pp. 325–333). Wageningen, The Netherlands: International Society of Biotelemetry.

Brito-Ríos, J. G. A. (2017). Estado de conservación de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis) en cuencas de la Reserva de la Biósfera Sierra de Manantlán (Tesis de maestría). Universidad de Guadalajara. Guadalajara, Mexico.

Bushaw, J. D., Ringelman, K. M., & Rohwer, F. C. (2019). Applications of unmanned aerial vehicles to survey mesocarnivores. Drones, 3, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones3010028

Calmé, S., & Sanvicente, M. (2009). Distribución, uso de hábitat y amenazas para la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens): un enfoque etnozoológico. In J. Espinoza Ávalos, I. Islebe, & H. Hernández (Eds.), El sistema ecológico de la bahía de Chetumal, costa del Caribe mexicano (pp. 124–130). Chetumal: El Colegio de la Frontera Sur.

Casariego, M. A. (2013). Sitios utilizados por la nutria neotropical en una selva baja caducifolia en la costa de Oaxaca, México. Therya, 4, 603–615. https://doi.org/10.12933/therya-13-137

Ceballos-Martínez, R. R. (2002). Geografía y medio ambiente en el sistema lagunar San Felipe-Bacalar-Guerrero. In F. J. Rosado-May, R. Romero-Mayo, & A. De Jesús-Navarrete (Eds.), Contribuciones de la ciencia al manejo costero integrado de la bahía de Chetumal y su área de influencia (pp. 17–22). Chetumal: Universidad de Quintana Roo.

Chávez-Tovar, J. C. (2005a). Cabeza de viejo, viejo de monte. In G. Ceballos, & G. Oliva (Eds.), Los mamíferos silvestres de México (pp. 376–378). México D.F.: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad/ Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Chávez-Tovar, J. C. (2005b). Grisón. In G. Ceballos, & G. Oliva (Eds.), Los mamíferos silvestres de México (pp. 378–379). México D.F.: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad/ Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Christie, K. S., Gilbert, S. I., Brown, C. L., Hatfield, M., & Hanson, L. (2016). Unmanned aircraft systems in wildlife research: current and future applications of a transformative technology. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 14, 241–251. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1281

CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora). (2019). Apéndices I, II y III. Convención sobre el Comercio Internacional de Especies Amenazadas de Fauna y Flora Silvestres. CITES, UNEP. Recuperado el 01 julio, 2020 en: https://www.cites.org/esp/app/appendices.php

Cruz-García, F., Contreras-Balderas, A. J., García Salas, J. A., & Gallo-Reynoso, J. P. (2017). Dieta de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens) en Pueblo Nuevo, Durango, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 88, 701–709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmb.2017.07.001

DOF (Diario Oficial de la Federación). (2008, Abril 8). Decreto mediante el cual se modifica el similar por el que se declara como Área Natural Protegida la región conocida como Bahía de Chetumal, con la categoría de Zona sujeta a Conservación Ecológica, Santuario del Manatí, ubicada en el municipio de Othón P. 13.

Escobedo-Cabrera, E., Chablé-Jiménez, M., & Pool-Valdez, C. (2009). Mamíferos terrestres. In J. Espinoza-Ávalos, G. A. Islebe, & H. A. Hernández-Arana (Eds.), El sistema ecológico de la bahía de Chetumal/Corozal: costa occidental del mar Caribe (pp. 174–183). Chetumal: El Colegio de la Frontera Sur.

Escobedo-Cabrera, E., Ramírez-Santamaría, A., Esquivel-Pérez, Y., & Pozo de la Tijera, C. (2002). Mamíferos terrestres del santuario del manatí: Bahía de Chetumal, Quintana Roo, México, y su área de influencia. In F. J. Rosado-May, R. Romero-Mayo, & A. De Jesús-Navarrete (Eds.), Contribuciones de la ciencia al manejo costero integrado de la bahía de Chetumal y su área de influencia (pp. 107–114). Chetumal: Universidad de Quintana Roo.

Espinoza-Medinilla, E., Anzures-Dadda, A., & Cruz-Aldán, E. (1998). Mamíferos de la Reserva de la Biosfera El Triunfo, Chiapas. Revista Mexicana de Mastozoología, 3, 79–94.

Gallo-Reynoso, J. P. (1989). Distribución y estado actual de la nutria o perro de agua (Lutra longicaudis annectens Major, 1897) en la sierra Madre del Sur, México (Tesis de maestría). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City.

Gallo-Reynoso, J. P. (1997). Situación y distribución de las nutrias en México, con énfasis en Lontra longicaudis annectens Major, 1897. Revista Mexicana de Mastozoología, 2, 10–32.

Gallo-Reynoso, J. P., & Casariego, M. A. (2005). Nutria de río, perro de agua. In G. Ceballos, & G. Oliva (Eds.), Los mamíferos silvestres de México (pp. 374–376). México D.F.: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad/ Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Gallo-Reynoso, J. P., Macías-Sánchez, S., Nuñez-Ramos, V. A., Loya-Jaquez, A., Barba-Acuña, I. D., Armenta-Méndez, L. C. et al. (2019). Identity and distribution of the Neartic otter (Lontra canadensis) at the Río Conchos Basin, Chihuahua, Mexico. Therya, 10, 243–253. https://doi.org/10.12933/therya-19-894

Gallo-Reynoso, J. P., & Meiners, M. (2018). Las nutrias de río de México. Biodiversitas, 140, 2–7.

Gallo-Reynoso, J. P., Ramos-Rosas, N., & Rangel-Aguilar, Ó. (2008). Depredación de aves acuáticas por la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens), en el río Yaqui, Sonora, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 79, 275–279. https://doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2008.001.502

Gamboa-Pérez, H. C. (1991). Ictiofauna dulceacuícola en la zona sur de Quintana Roo. In T. Camarena-Luhrs, & S. I. Salazar-Vallejo (Eds.), Estudios ecológicos preliminares de la zona sur de Quintana Roo (pp. 186–197). Chetumal: Centro de Investigaciones de Quintana Roo.

García-Silva, O., Gallo-Reynoso, J. P., Bucio-Pachecho, M., Medrano-López, J., Meza-Inostroza, P., & Grave-Partida, R. (2021). Neotropical otter diet variation between a lentic and a lotic systems. Therya, 12, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.12933/therya-21-781

Gómez-Pech, E. H., Barrasa-García, S., & García de Fuentes, A. (2018). Paisaje litoral de la laguna de Bacalar (Quintana Roo, México): ocupación del suelo y producción del imaginario por el turismo. Investigaciones Geográficas, 95, 1–18. https://doi.org/dx.doi.org/10.14350/rig.59532

Guerrero-Flores, J. J., Macías-Sánchez, S., Mundo-Hernández, V., & Méndez-Sánchez, F. (2013). Ecología de la nutria (Lontra longicaudis) en el municipio de Temascaltepec, Estado de México: estudio de caso. Therya, 4, 231–242. https://doi.org/10.12933/therya-13-127

Hernández-Arana, H. A., Vega-Zepeda, A., Ruíz-Zárate, M. A., Falcón-Álvarez, L. I., López-Adame, H., Herrera-Silveira et al. (2015). Transverse Coastal Corridor: from freshwater lakes to coral reefs ecosystems. In G. A. Islebe, S. Calmé, J. L. León-Cortés, & B. Schmook (Eds.), Biodiversity and conservation of the Yucatán Peninsula (pp. 355–376). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-06529-8_14

Ibarra-Madrigal, S. M., Gracia, M. A., Schmook, B., & Hernández-Arana, H. A. (2020). Ordenamiento territorial, agua subterránea y participación sociopolítica en Bacalar, Quintana Roo, México. Sociedad y Ambiente, 22, 265–292. https://doi.org/10.31840/sya.vi22.2112

INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía). (2020). Censo de población y vivienda 2020. Recuperado el 7 julio, 2021 en: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2020/#Microdatos

Juárez-Sánchez, D., Blake, J. G., & Hellgreen, E. C. (2019). Variation in Neotropical river otter (Lontra longicaudis) diet: effect of an invasive prey species. Plos One, 14, e0217727. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217727

Kruuk, H. (2006). Otters: ecology, behavior and conservation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Larivière, S. (1999). Lontra longicaudis. Mammalian Species, 609, 1–5.

Laurentino, I., Sousa, R., Corso, G., & Sousa-Lima, R. (2019). To eat or not eat: ingestion and avoidance of fecal content from communal latrines of Lontra longicaudis (Olfers, 1818). Latin American Journal of Aquatic Mammals, 14, 2–8. https://doi.org/10.5597/lajam00248

Lorenzo, C., Espinoza, E. E., Naranjo, E. J., & Bolaños, E. J. (2008). Mamíferos terrestres de la Frontera Sur de México. In C. Lorenzo, E. Espinoza, & J. Ortega (Eds.), Avances en el estudio de los mamíferos de México, Vol. II (pp. 147–164). México D.F.: Asociación Mexicana de Mastozoología, A. C.

Ma, H., Stewart, K., Lougheed, S., Zheng, J., Wang, Y., & Zhao, J. (2016). Characterization, optimization, and validation of environmental DNA (eDNA) markers to detect an endangered aquatic mammal. Conservation Genetics Resources, 8, 561–568. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12686-016-0597-9

Macías-Sánchez, S. (2003). Evaluación del hábitat de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis Olfers, 1818) en dos ríos de la zona centro del estado de Veracruz, México (Tesis de maestría). Instituto de Ecología, A.C., Xalapa, Ver.

Michalski, F., Martins, C., Rheingantz, M., & Norris, D. (2021). New scent marking behavior of neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis) in the Eastern Brazilian Amazon. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin, 38, 28–37.

Morales-Vela, B. y Olivera-Gómez, L. D. (1991). Mamíferos acuáticos. In T. Camarena-Luhrs, & S. Salazar-Vallejo (Eds.), Estudios ecológicos preliminares de la zona sur de Quintana Roo (pp. 172–185). Chetumal: Centro de Investigaciones de Quintana Roo.

Morales-Vela, B., & Olivera-Gómez, L. D. (1994). Mamíferos acuáticos y su protección en la zona fronteriza México-Belice. In E. Suárez-Morales (Ed.), Estudio integral de la frontera México-Belice (pp. 197–211). Chetumal: Centro de Investigaciones de Quintana Roo.

Morales-Vela, B., Padilla-Saldívar, J. A., & Antochiw-Alonzo, D. M. (2011). Mamíferos marinos. In C. Pozo (Ed.), Riqueza biológica de Quintana Roo. Un análisis para su conservación, Tomo II. (pp. 233–239). México D.F.: ECOSUR/ Conabio/Gobierno del Estado de Quintana Roo/ PPD.

Morón-Ríos, M. A. (2011). Escarabajos. In C. Pozo de la Tijera (Ed.), Riqueza biológica de Quintana Roo. Un análisis para su conservación. Tomo II (pp. 182–185). México D.F.: ECOSUR/ Conabio/ Gobierno del Estado de Quintana Roo/ PPD.

Muãnis, M. C., & Oliveira, L. F. B. (2011). Habitat use and food niche overlap by Neotropical otter, Lontra longicaudis, and Giant otter, Pteronura brasiliensis, in the Pantanal Wetland, Brazil. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin, 28, 76–85.

Orozco-Meyer, A. (1998). Tendencia de la distribución y abundancia de la nutria de río (Lontra longicaudis annectens Major, 1897), en la ribera del río Hondo, Quintana Roo, México. (Tesis). Instituto Tecnológico de Chetumal.

Padgett-Stewart, T. M., Wilcox, T. M., Carim, K. J., McKelvey, K. S., Young, M. K., & Schwartz, M. K. (2016). An eDNA assay for river otter detection: a tool for surveying a semi-aquatic mammal. Conservation Genetics Resources, 8, 5–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12686-015-0511-x

Pardini, R., & Trajano, E. (1999). Use of shelters by the Neotropical river otter (Lontra longicaudis) in an Atlantic Forest stream, southeastern Brazil. Journal of Mammalogy, 80, 600–610.

Platt, S. G., & Rainwater, T. R. (2011). Predation by Neotropical otters (Lontra longicaudis) on turtles in Belize. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin, 28, 4–10.

Pozo de la Tijera, C. (1997). Formación de las colecciones de referencia de aves y mamíferos de la Reserva de la Biósfera de Sian Ka’an, Quintana Roo, México. El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Unidad Chetumal. Informe final SNIB-CONABIO. Proyecto No. B114. México D.F.

Pozo de la Tijera, C., Rangel, L., & Viveros, P. (1991). Fauna. In T. Camarena, & S. Salazar (Eds.), Estudios ecológicos preliminares de la zona sur de Quintana Roo (pp. 49–78). Chetumal: Centro de Investigaciones de Quintana Roo.

Rangel-Aguilar, Ó., & Gallo-Reynoso, J. P. (2013). Hábitos alimentarios de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens) en el Río Bavispe-Yaqui, Sonora, México. Therya, 4, 297–309. https://doi.org/10.12933/therya-13-135

Reid, F. (1997). A field guide to the mammals of Central America and southeast México. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rheingantz, M. L., Rosas-Ribeiro, P., Gallo-Reynoso, J., Fonseca da Silva, V. C., Wallace, R., Utreras, V. et al. (2021). Lontra longicaudis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021: E.T12304A164577708. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T12304A164577708.en

Rheingantz, M., Santiago-Plata, V. M., & Trinca, C. S. (2017). The Neotropical otter Lontra longicaudis: a comprehensive update on the current knowledge and conservation status of this semiaquatic carnivore. Mammal Review, 47, 291–305.

Roberts, N. J., Clark, R. M., & Williams, D. (2016). Otter (Lontra longicaudis) spraint and mucus depositions: early ecological insights into the differences in marking site selection and implications for monitoring prey availability. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin, 33, 8–17.

Santiago-Plata, V. M., Valdez-Leal, J. D., Pacheco-Figueroa, C. J., de la Cruz-Burelo, F., & Moguel-Ordóñez, E. J. (2013). Aspectos ecológicos de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens) en el camino La Valeta en la Laguna de Términos, Campeche, México. Therya, 4, 265–280. https://doi.org/10.12933/therya-13-131

Semarnat (Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales). (2015). Programa de ordenamiento ecológico local del municipio de Othón P. Blanco, Quintana Roo. México D.F.: Semarnat.

Semarnat (Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales). (2010). Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-059-ECOL-2010, Protección ambiental-Especies nativas de México de flora y fauna silvestres-Categorías de riesgo y especificaciones para su inclusión, exclusión o cambio-Lista de especies en riesgo, publicada el 30 de diciembre de 2010. Diario Oficial de La Federación, México D.F.

SMN (Servicio Meteorológico Nacional) & Conagua (Comisión Nacional del Agua). (2020). Normales climatológicas por Estado. https://smn.conagua.gob.mx/tools/RESOURCES/Mensuales/qroo/00023171.TXT

Tobón-Velázquez, N. I., Rebolledo-Vieyra, M., Paytan, A., Broach, K. H., & Hernández-Terrones, L. M. (2019). Hydrochemistry and carbonate sediment characterisation of Bacalar Lagoon, Mexican Caribbean. Marine and Freshwater Research, 70, 382–394. https://doi.org/10.1071/MF18035

Trujillo, F. y Arcila, D. (2006). Nutria neotropical Lontra longicaudis. In J. V. Rodríguez-M., M. Alberico, F. Trujillo y J. Jorgenson (Eds.), Libro rojo de los mamíferos de Colombia. Serie de libros rojos de especies amenazadas de Colombia. (pp. 249–254). Bogotá: Conservación Internacional Colombia, Ministerio de Ambiente, Vivienda y Desarrollo Territorial.

Valdez-Moreno, M., Ivanova, N. V., Elías-Gutiérrez, M., Pedersen, S. L., Bessonov, K., & Hebert, P. D. N. (2019). Using eDNA to biomonitor the fish community in a tropical oligotrophic lake. Plos One, 14, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215505

Valenzuela-Galván, D. (2005). Mapache. In G. Ceballos y G. Oliva (Eds.), Los mamíferos silvestres de México (pp. 415–417). México D.F.: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad/ Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Wagnon, C. J., & Serfass, T. L. (2016). Camera traps at northern river otter latrines enhance carnivore detectability along riparian areas in eastern North America. Global Ecology and Conservation, 8, 138–143.

Yanez-Montalvo, A., Gómez-Acata, S., Águila, B., Hernández-Arana, H., & Falcón, L. I. (2020). The microbiome of modern microbialites in Bacalar Lagoon, Mexico. Plos One, 15, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230071