Distribution, status and conservation needs of the white-sided jackrabbit, Lepus callotis (Lagomorpha)

David E. Brown a, Myles B. Traphagen b, Consuelo Lorenzo c, *, Martha Gomez-Sapiens b, d

a School of Life Sciences, Arizona State University, PO Box 874501, Tempe, Arizona 85287-4501, USA

b Wildlands Network, Borderlands Program, PO Box 3539, Tucson, Arizona 85719, USA

c Departamento de Conservación de la Biodiversidad, El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Unidad San Cristóbal, Carretera Panamericana y Periférico Sur s/n, Barrio de María Auxiliadora, 29290 San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico

d Department of Geosciences, University of Arizona, 1040 E. 4th Street, PO Box 85721, Tucson, Arizona, USA

*Corresponding author: clorenzo@ecosur.mx (C. Lorenzo)

Abstract

Although an important game animal and a species of wide distribution, little is known about the natural history of the white-sided jackrabbit (Lepus callotis), its ecological requirements, and limiting factors. The information available suggests that this species may have undergone a reduction in both population numbers and distribution, and may be endangered due to habitat changes. The information presented herein should facilitate proposals for future research, and conservation and management actions.

Keywords:

Conservation; Distribution; Lepus callotis

© 2018 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. Este es un artículo Open Access bajo la licencia CC BY-NC-ND

Distribución, estado y necesidades de conservación de la liebre de costados blancos Lepus callotis (Lagomorpha)

Resumen

Aunque se considera un animal de caza importante y una especie de amplia distribución, poco se conoce sobre la historia natural de la liebre torda (Lepus callotis), sus requerimientos ecológicos y factores limitantes. La información disponible sugiere que esta especie pudo haber sufrido una reducción del tamaño poblacional y de su distribución y puede estar en peligro debido a los cambios de hábitat. La información aquí presentada debe facilitar las propuestas para investigaciones futuras y acciones de conservación y manejo.

Palabras clave:

Conservación; Distribución; Lepus callotis

Despite having been described by scientists as early as 1830, and being a popular game animal throughout much of Mexico, the natural history and ecological requirements of the white-sided jackrabbit, Lepus callotis are almost unknown (Nelson, 1909). Presently divided into 2 subspecies along parallel 25 N, the nominate species, L. c. callotis occurs in tropic-subtropic savannas, encinales, warm-temperate rosetofilo scrub, juniper woodland, and halophytic vegetation south of the Nazas River from central Durango, through to the northwestern half of Oaxaca, and the northern half of Guerrero (Delgadillo-Quezada, 2011; Leopold, 1972). North of the Nazas River, L. c. gaillardi is found in temperate grasslands in northern Durango, Chihuahua, and extreme southern New Mexico in the United States (Anderson & Gaunt, 1962; Bednarz, 1977; Cook, 1986; Desmond, 2004), and is positively correlated with buffalograss (Buchloe dactyloides) in New Mexico and Chihuahua (Traphagen, 2002, 2011). The Nazas River has been considered a significant geographical barrier between the separations of subspecies of L. callotis (Petersen, 1976).

Lepus c. gaillardi differs from L. c. callotis in having paler and buffier pelage including a paler rump and an ochraceous throat patch. The white flanks of L. c. gaillardi also show less contrast with the upper body fur of L. c. callotis, while the skulls are typically larger and have a more elevated supraorbital process. Lepus c. gaillardi also has a brown rather than black nape markings and measures larger for body, foot and ear length (Anderson & Gaunt, 1962).

Most of the information available on L. callotis comes from anecdotal observations made by museum collectors and scientists conducting general zoological inventories (e.g., Nelson, 1909). Although a few life history studies of L. c. gaillardi have been conducted (e.g., Bednarz, 1977; Bednarz & Cook, 1984; Desmond, 2004: Traphagen, 2011) only one study has investigated the status of L. c. callotis (Delgadillo-Quezada, 2011). All of the information available suggests that L. c. gaillardi is in serious decline due to environmental changes resulting from overgrazing, shrub invasion and other habitat changes (Dalquest, 1953; Matson & Baker, 1986; Traphagen, 2011). Traphagen (2011) suggested that road kills from US Border Patrol activities may be a significant factor contributing to declining numbers in New Mexico, USA (Fig. 1). The status of L. c. callotis is less clear, but the limited

http://rev.mex.biodivers.unam.mx/wp-content/uploads/2018/vol-89/89-1-mar-2018/html/28-Fig1.tif

Figure 1. Photo of a pair of Lepus callotis gaillardi killed by a vehicle in New Mexico, USA. The larger specimen is a female.

information available for this subspecies indicates that it may also be in trouble due to destruction of its habitat, hunting, disturbance by herders and their dogs, as well as vehicle collisions (Bello-Sánchez, 2010). Additionally, a study that modeled the effects of climate change on grassland mammals in Mexico predicted an 80% reduction in range and habitat of L. callotis by 2050 (Trejo et al.,

2011).

Several investigators (Bogan & Jones, 1975; Dalquest, 1953; Davis & Lukens, 1958; Davis & Russell, 1954; Findley et al., 1975; Hall & Villa, 1949; Leopold, 1972; Matson & Baker, 1986; Sánchez et al., 2014) reported L. callotis to be uncommon in both New Mexico and Mexico (Chihuahua, Guanajuato, Guerrero, Michoacán, southeastern Morelos, San Luis Potosí, Zacatecas). We fear that populations of L. callotis have been diminishing for years, and in some areas are now rare where formerly common. In other areas the species has been or is being replaced by the highly adaptable black-tailed jackrabbit (L. californicus; Baker & Greer, 1962; Desmond, 2004; Hall, 1981). In the Chihuahuan Desert region, L. c. gaillardi has been considered a “mammal in distress” (Baker, 1977). In the United States it has been classified as “threatened” by the State of New Mexico since 1975; however, it is not afforded any protection by the United States federal government under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). In 2009 the United States Fish and Wildlife was petitioned to list the species under the ESA, but it was rejected after a 12-month review due to only limited information being available on the status of the species in Mexico (United States Fish and Wildlife Service, 2009, 2010). This decision runs counter to the overwhelming number of publications and proceedings which have recommended the species to be considered as endangered throughout its range and in need of research and protection (Baker, 1977; Conway, 1976; Dunn et al., 1982; Findley & Caire, 1977; Wilson & Reeder, 1993). In Mexico, however, the species is not considered to be in “at risk” category (Semarnat, 2010).

In this paper we summarize the distributional records and few studies pertaining to L. callotis. Our purpose is to encourage future field surveys to document current and future threats to the animal’s existence, and to alert governments, academic institutions, and wildlife management agencies as to how little is known of the general occurrence, life history, habitat affiliations, and general welfare of this species.

Using Google Scholar, we reviewed scientific literature about L. callotis, abstracted pertinent information, and plotted collection locales on Google Earth. Collection locations for 281 specimens of L. callotis were obtained from databases in the Mammal Networked Information System (MaNIS; http://www.manisnet.org) and the

http://rev.mex.biodivers.unam.mx/wp-content/uploads/2018/vol-89/89-1-mar-2018/html/28-Fig2.tif

Figure 2. Collection records for Lepus callotis gaillardi (triangles) and L. c. callotis (circles) from 1890 to 1990.

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF; http://www.gbif.org). The latitude, longitude, and elevation of these locations were recorded and plotted on

a map.

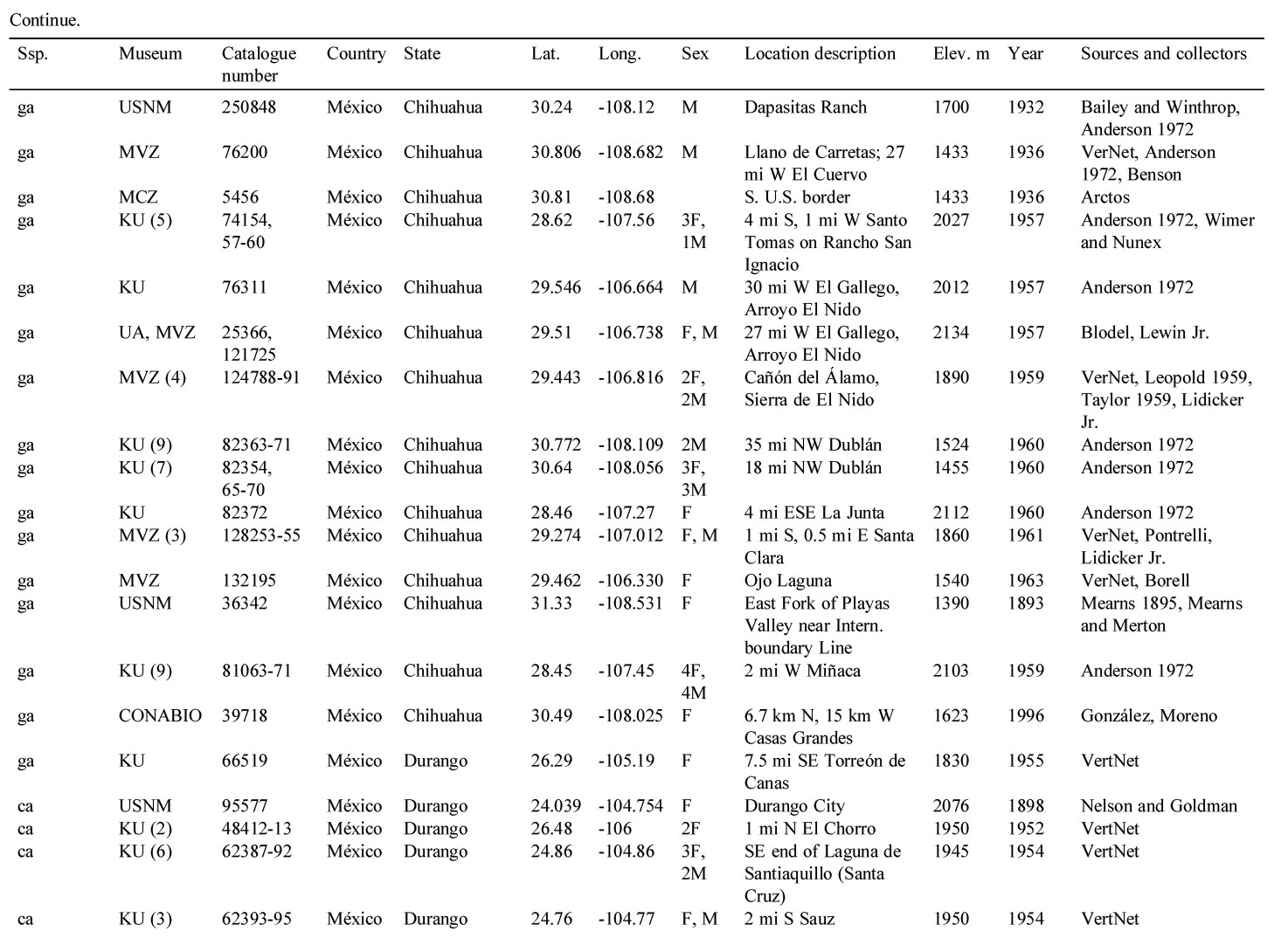

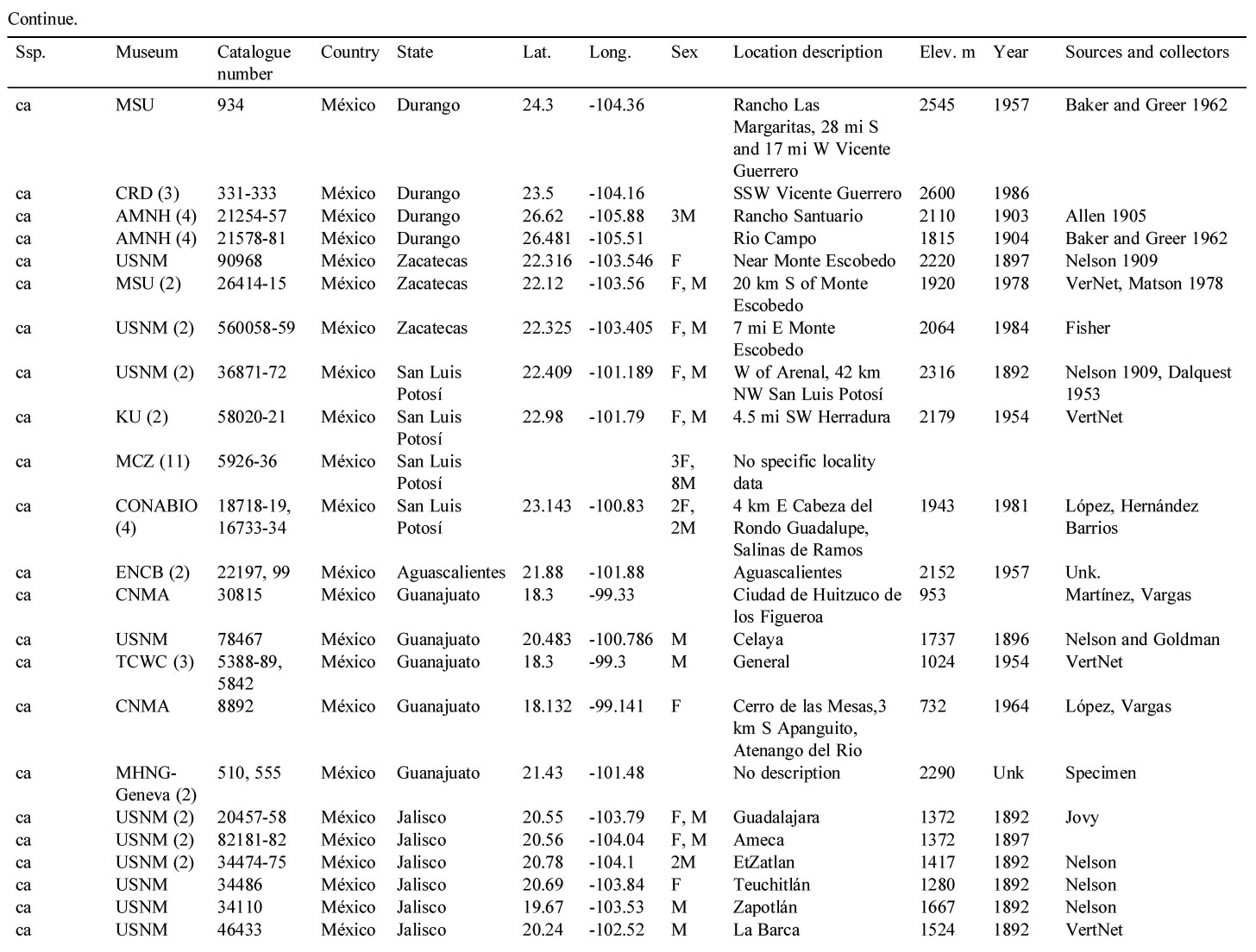

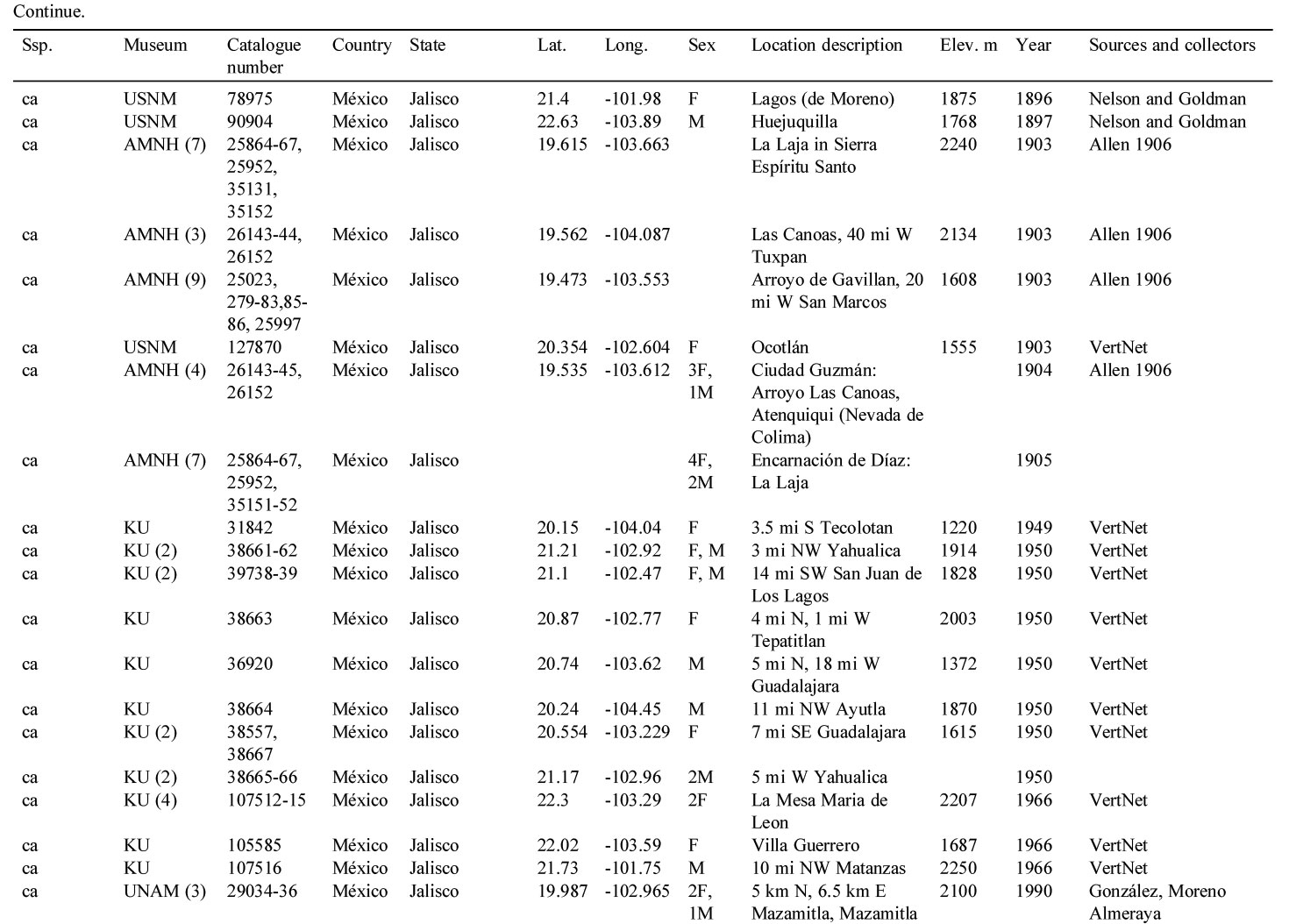

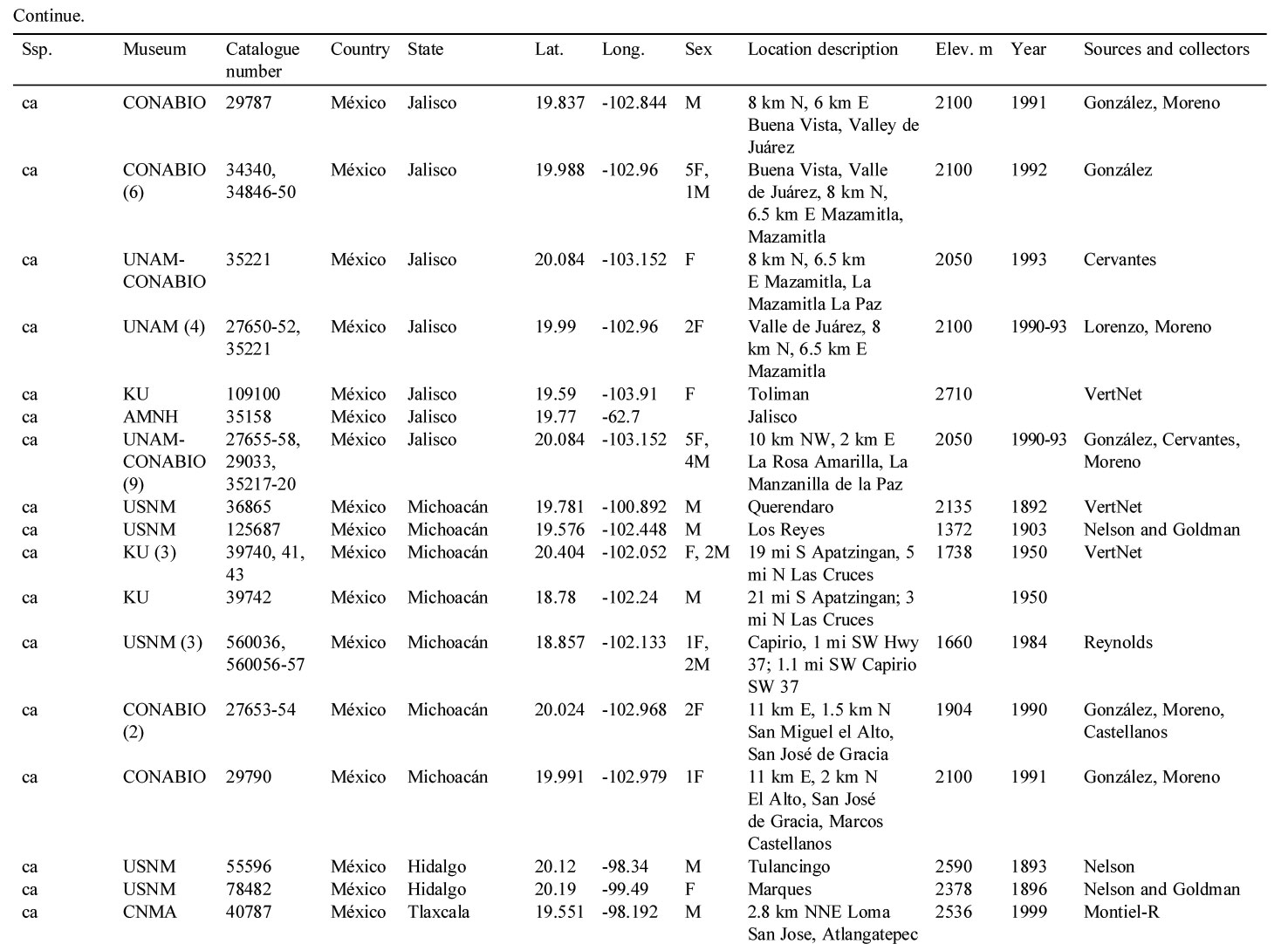

We located 202 specimens of L. c. callotis from 84 localities, and 79 specimens of L. c. gaillardi from 28 locations in museum collections (Table 1; Fig. 2). The collections with the most specimens are in the U.S. National Museum (Smithsonian) and American Museum of Natural History. Museum specimens were collected from the Mexican states of Aguascalientes, Chihuahua, Distrito Federal, Durango, Guanajuato, Guerrero, Hidalgo, Jalisco, Michoacán, Morelos, Oaxaca, Puebla, San Luis Potosí, Mexico, Tlaxcala, and Zacatecas. States less well represented were Michoacán and Guerrero. All of the United States specimens are from southwestern New Mexico. Elevations ranged from 660 to 2,600 m. The proportion of males to females was 54:58, which was not significantly different than 1:1. Localities plotted on Google Earth suggest that most sites are in open grassland.

Lepus c. callotis was originally described as a species in 1830 by Wagler from specimens collected at the southern end of “Mexican tableland”, Lepus c. gaillardi was originally described as a species in 1895 by E. A. Mearns from a series of specimens collected on the USA Boundary Survey including a holotype specimen from Chihuahua. After 1904, there is a gap of 27 years without any collected specimens of either subspecies due to armed conflicts initiated in 1910 with the Mexican Revolution. It was not until 1931 that L. c. gaillardi and L. c. callotis were again collected. We found no records of the species in collections dated after 1999 when the animal was completely protected in New Mexico and after the onset of the current period of insecurity in rural Mexico.

Lepus callotis is considered as “near threatened” in the IUCN red list (IUCN 2017), however, biological information is scarce, and the actual distribution and status of L. callotis are unknown, particularly in Mexico where most of its distribution occurs. We propose a detailed, long term study of the mortality factors effecting L. callotis, and an investigation into the taxonomy of this species, since the subspecies have morphologic and ecological differences that may influence conservation actions.

We assembled a table of museum collection locales (Table 1) so that biologists might better understand the status of L. callotis and alert governments, academic institutions, and wildlife management agencies of how little is known about general occurrence, life history and habitat affiliations of this animal. Hopefully, this information will encourage further study into the animal’s ecological affiliations, habitat requirements, and general welfare lest it disappear without its natural history being understood.

We thank D. Navarrete for her help drawing Figure 2. Comments from two anonymous reviewers improved this research note.

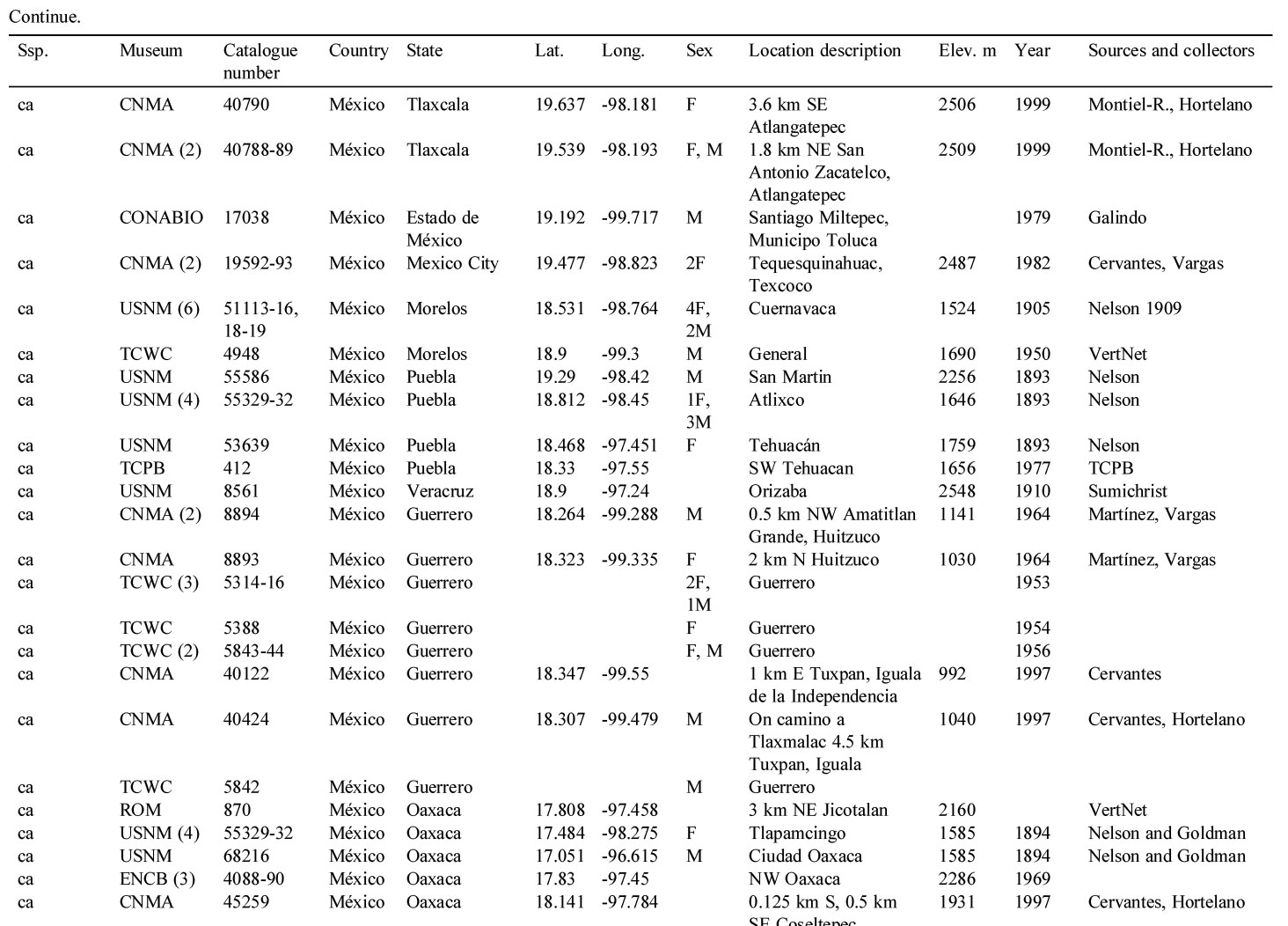

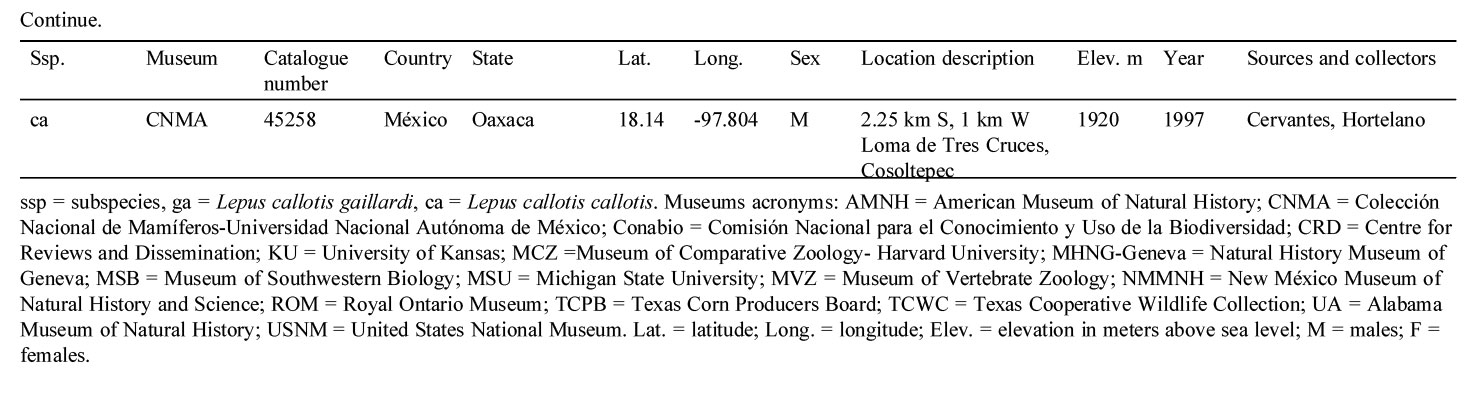

Table 1

Summary of Lepus callotis specimens (number in parenthesis) and locations in North American collections.

References

Anderson, S., & Gaunt, A. S. (1962). A classification of the white-sided jackrabbits of Mexico. American Museum Novitates, 2088, 1–16.

Baker, R. H. (1977). Mammals of the Chihuahuan Desert region – future prospects. In H. Wauer, & D. H. Riskind (Eds.), Transactions of the symposium on the biological resources of the Chihuahuan Desert region, United States and Mexico. United States National Park Service Transactions and Proceedings Series, 3, 221–225.

Baker, R. H., & Greer, J. K. (1962). Mammals of the Mexican state of Durango. Publications of Museum Michigan State University Biology, Series, 35, 25–154.

Bednarz, J. (1977). The white-sided jackrabbit in New Mexico: distribution, numbers, and biology in the grasslands of Hidalgo County. Santa Fe, New Mexico: New Mexico Game and Fish Department.

Bednarz, J., & Cook, J. (1984). Distribution and numbers of the white-sided jackrabbit (Lepus callotis gaillardi) in New Mexico. The Southwestern Naturalist, 29, 358–360.

Bello-Sánchez, R. A. (2010). Distribución y abundancia de la liebre torda Lepus callotis (Wagler, 1830) en el valle de Perote, Veracruz (Ph.D. Thesis). Universidad Veracruzana. Veracruz, Mexico.

Bogan, M. A., & Jones, C. (1975). Observations on Lepus callotis in New Mexico. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington, 88, 45–50.

Conway, M. C. (1976). A rare hare. New Mexico Wildlife, 21, 21–23.

Cook, J. A. (1986). The mammals of the Animas Mountains and adjacent areas, Hidalgo County, New Mexico. Occasional Papers of the Museum of Southwestern Biology, 4, 1–45.

Dalquest, W. W. (1953). Mammals of the Mexican state of San Luis Potosí. Louisiana State University Studies Biological Science Series 1. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press.

Davis, W. B., & Lukens Jr., P. W. (1958). Mammals of the Mexican state of Guerrero exclusive of Chiroptera and Rodentia. Journal of Mammalogy, 39, 347–367.

Davis, W. B., & Russell, R. J. (1954). Mammals of the Mexican state of Morelos. Journal of Mammalogy, 35, 63–80.

Delgadillo-Quezada, G. (2011). Distribución, selección de hábitat y densidad de la liebre torda (Lepus callotis, Wagler, 1830) en el Valle de Perote (Ph.D. Thesis). Instituto de Ecología, A.C., Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico.

Desmond, M. J. (2004). Habitat associations and co-occurrence of Chihuahuan Desert hares (Lepus californicus and L. callotis). The American Midland Naturalist, 151, 414–419.

Dunn, J. P., Chapman, J, A., & Marsh, R. E. (1982). Jackrabbits: Lepus californicus and allies. In A. Chapman, & G. A. Feldhamer (Eds.), Wild mammals of North America: biology, management, and economics (pp. 124–145). Baltimore, Maryland: John Hopkins University Press.

Findley, J. S., & Caire, W. (1977). The status of mammals in the northern region of the Chihuahuan Desert. In H. Wauer, & D. H. Riskind (Eds.), Transactions of the symposium on the biological resources of the Chihuahuan Desert region United States and Mexico. United States National Park Service Transactions and Proceedings Series, 3, 127–139.

Findley, J. S., Harris, A. H., Wilson, D. E., & Jones, C. (1975). Mammals of New Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Hall, E. R. (1981). The mammals of North America. 2nd Ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Hall, E. R., & Villa, B. (1949). An annotated check list of the mammals of Michoacán, Mexico. University of Kansas Publications Museum Natural History, 1, 431–472.

IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature). (2017). IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2017.3. Disponible en: www.iucnredlist.org

Leopold, A. S. (1972). Wildlife of Mexico: the game birds and mammals. Berkeley, California: University of California Press.

Matson, J. O. & Baker, R. H. (1986). Mammals of Zacatecas. Special Publication Museum Texas Tech Univerisy, 24, 1–88.

Mearns, E. A. (1895). Preliminary description of a new subgenus and six species and subspecies of hares, from the Mexican border of the United States. Proceedings of the United States National Museum, 18, 551–565.

Nelson, E. W. (1909). The rabbits of North America. North American Fauna, 29, 1–314.

Petersen, M. K. (1976). The Rio Nazas as a factor in mammalian distribution in Durango, Mexico. The Southwestern Naturalist, 20, 495–502.

Sánchez, Ó., Magaña-Cota, G., Téllez-Girón, G., López-Forment, W., & Urbano Vidales, G. (2014). Mamíferos no voladores de Guanajuato, México: revisión histórica y lista taxonómica actualizada. Universidad de Guanajuato Acta Universitaria, 24, 1–37.

Semarnat (Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales). (2010). Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010, Protección ambiental-Especies nativas de México de flora y fauna silvestres- Categorías de riesgo y especificaciones para su inclusión, exclusión o cambio- Lista de especies en riesgo. Diario Oficial de la Federación, 30 de diciembre de 2010, Segunda Sección, México.

Traphagen, M. B. (2002). Buffalograss (Bűchloe dactyloides): an important grass species for predicting the presence of the white-sided jackrabbit (Lepus callotis) in southern New Mexico. Albuquerque: New Mexico Game and Fish Contract Report #02-515-43.

Traphagen, M. B. (2011). Final report on the status of the white-sided jackrabbit (Lepus callotis gaillardi) in New Mexico. Santa Fe, New Mexico: New Mexico Department of Game and Fish.

Trejo, I., Martínez-Meyer, E., Calixto-Pérez, E., Sánchez-Colón, S., Vásquez-de la Torre, R., & Villers-Ruiz, L. (2011). Analysis of the effects of climate change on plant communities and mammals in Mexico. Atmósfera, 24, 1–14.

United States Fish and Wildlife Service. (2009). 90-Day finding on a petition to list the white-sided jackrabbit (Lepus callotis) as threatened or endangered. Federal Register, 74, 36152–36158.

United States Fish and Wildlife Service. (2010). 12-month finding on a petition to list the white-sided jackrabbit as threatened or endangered. Federal Register, 75, 53615–53629.

Wagler, J. (1830). Natürliches system der amphibian, mit vorangehender Classification der Säugthiere und Vögel. Munich, Germany: J. G. Cottahehen Buchhandlung.

Wilson, D. E., & Reeder, D. M. (1993). Mammal species of the world: a taxonomic and geographic reference. 2nd ed. Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press, American Society of Mammalogists.