Rosa M. Manzo a, b, *, M. Manuela Dadamia a, Susana Rizzuto a, c

a Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia San Juan Bosco, Laboratorio de Investigaciones en Evolución y Biodiversidad, Ruta N° 259, Km 16.5, 9200 Esquel, Chubut, Argentina

b Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, Godoy Cruz 2290, B1766 Buenos Aires, Argentina

c Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia San Juan Bosco, Centro de Investigación Esquel de Montaña y Estepa Patagónica, Roca 780, 9200 Esquel, Chubut, Argentina

*Corresponding author: rosamanzo19@gmail.com (R.M. Manzo)

Received: 7 April 2020; accepted: 31 August 2020

Abstract

A study of oribatid mite communities in a Patagonian forest affected by wildfires was carried out to assess their taxonomic diversity and to increase knowledge of their distribution. A total of 43 species/morphospecies were found. Ten were new records for Chubut and 3 for Argentina. Increased knowledge of this fauna will be fundamental in aiding further understanding about its ecology and distribution.

Keywords: New records; National Park; Chubut

© 2021 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license

Nuevos registros de ácaros oribátidos (Acari: Oribatida) de un bosque patagónico afectado por fuego en Argentina

Resumen

Se llevó a cabo un estudio de la comunidad de ácaros oribátidos de un bosque afectado por fuego ubicado en la Patagonia argentina para evaluar su diversidad taxonómica e incrementar el conocimiento de su distribución. Un total de 43 especies/morfoespecies fueron encontradas; del total, 10 fueron nuevos registros para la provincia de Chubut y 3 fueron nuevos registros para la Argentina. Incrementar el conocimiento de esta fauna se vuelve fundamental para ayudar a comprender su ecología y distribución.

Palabras claves: Nuevos registros; Parque Nacional, Chubut

© 2021 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. Este es un artículo Open Access bajo la licencia CC BY-NC-ND

Introduction

Naturally generated fire has an important role in the maintenance and evolution of ecosystems and has been an essential part of human life systems since ancient times (Bowman et al., 2011). In some forest ecosystems, fires are vital and essential for the process of ecological succession and for maintaining stability (Knicker, 2007). Such stability has been disrupted because of increasingly aggressive human action on renewable natural resources. In fact, intentional burning and anthropogenic large-scale forest fires have caused the loss and degradation of extensive forest areas (Castillo-Soto, 2006). Fire is the most prominent large-scale disturbance regime in many of the world´s ecosystems, including forests and grasslands (Harnett, 1991; Hobbs & Atkins, 1990; Jonson, 1992; Liacos, 1977; Malmström, 2010). Historic fire regimes vary greatly across the different ecosystem types in the southern Andean region, and the tree-ring record shows that before the 20th century, large, severe fires also played a significant ecological role in shaping even the wettest forests (Veblen et al., 2009). In Patagonia, and particularly in the Andean-Patagonian forests (Nothofagus spp.), anthropogenic fire has been a recurrent problem during the past century or so, both deliberate and accidental anthropic fires became very frequent, and in all cases influenced the development of vegetation in temperate forest regions (Donoso, 1997).

One of the direct impacts of wildfires is the death of micro- macro- and mesofauna, bacteria and fungi —indeed several studies have shown that soil animal numbers are markedly reduced by forest fires (Heyward & Tissot, 1936; Huhta et al., 1967; Malmström, 2008; Malmström et al., 2008; N’Dri et al., 2017; Pearse, 1943). The recovery rate of soil faunal communities after a fire is poorly understood because it is difficult to have many sites with similar conditions and similar severity of fire impact, so there are few papers about it (Zaitsev et al., 2016).

Oribatid mites mainly inhabit the soil-litter system and tend to be the dominant arthropod group in highly organic forest soils (Norton & Behan-Pelletier, 2009), with over 10,000 species described worldwide (Walter & Proctor, 2013). Studies of the oribatid fauna in Argentina are limited compared to other parts of the world (Kun et al., 2010). Recently, Fredes (2018) published a catalogue that provides an overview of the known Argentinian oribatid mite fauna. This catalogue includes a total of 398 described species comprising 185 genera and 75 families, but it does not include the findings of Ruiz et al. (2018) who reported 9 new records, and Manzo et al. (2019, 2020) reported 3 new records, raising the total number of species from Argentina to 410. In all cases, the aforementioned studies mainly analyzed material from the Andean Patagonian forests and steppe, but not from forests affected by wildfire. The aim of this study is to provide information on the Oribatid mites species present in a Patagonian forest (in Chubut) affected by wildfires, taking into consideration the new records for Chubut and Argentina.

Materials and methods

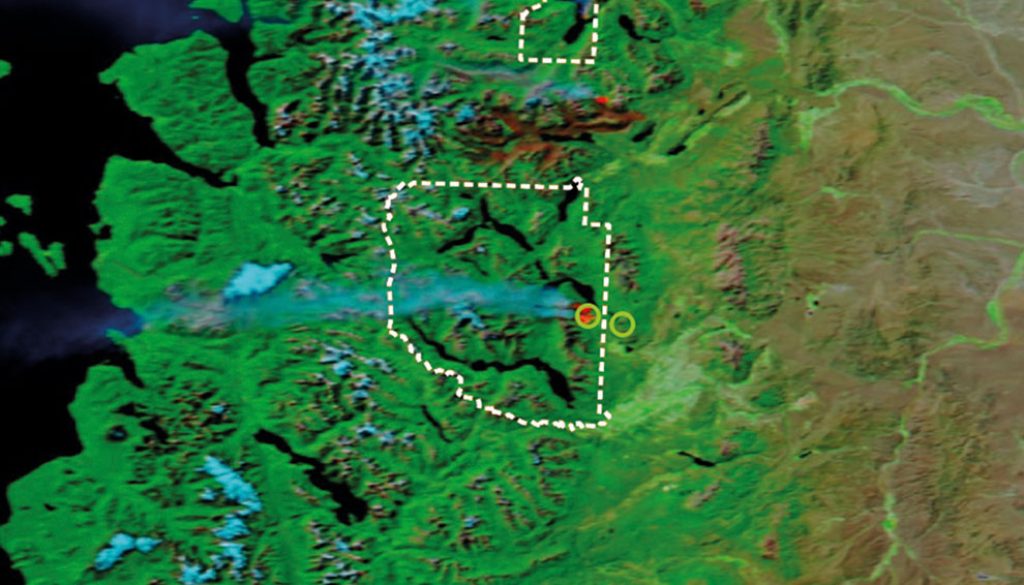

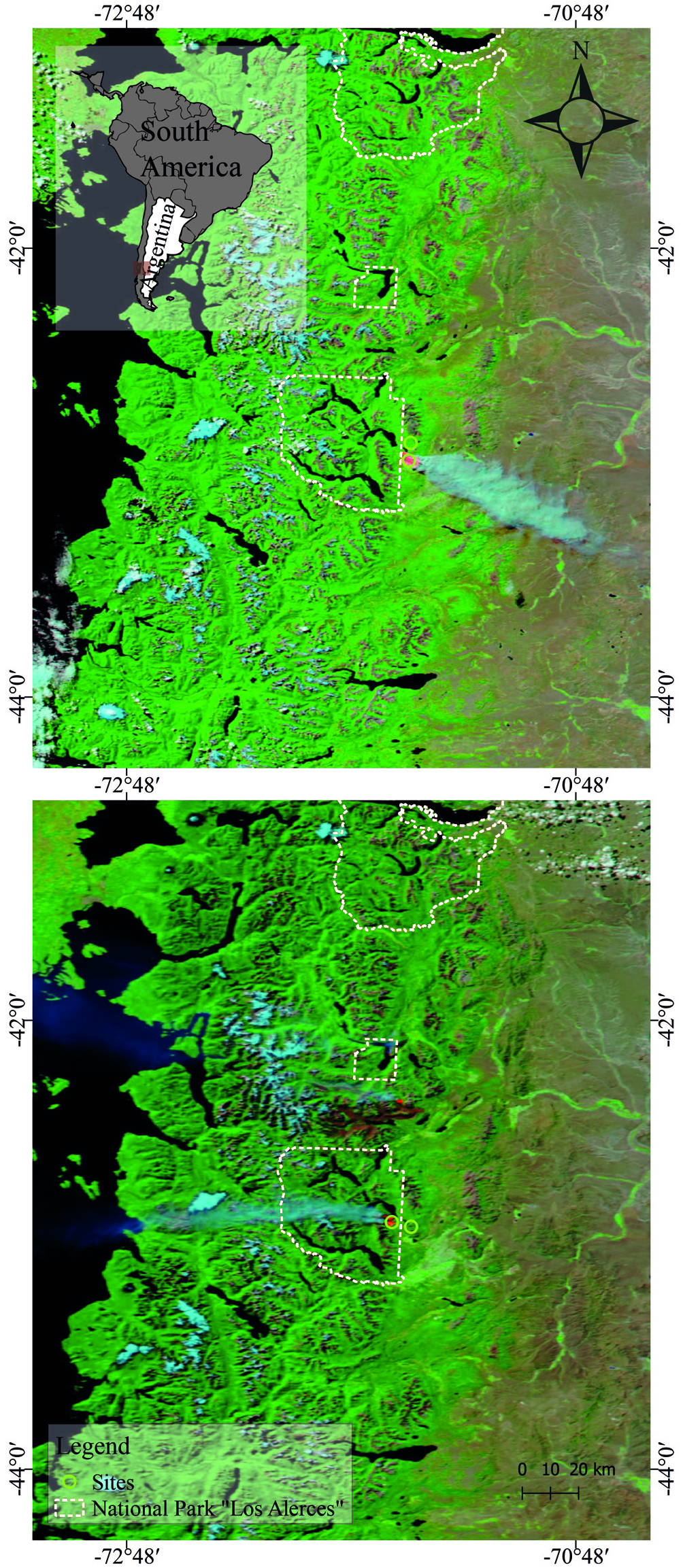

The study was carried out in a Nothofagus spp. forest where anthropogenic fire occurred both in 2008 and in 2015, in an area bordering Los Alerces National Park in the northwest of Chubut (Fig. 1). This forest is in the sub-Antarctic province of the deciduous forest district (Cabrera & Willink, 1980). The medium altitude of both areas (burnt and unburnt) is 1,000 m asl, with an annual average temperature of 8 °C. The soil is of sandy loam texture with a pH of 6.8 and 11.5% organic matter content and is classified as Andisols (Soil Survey Staff, 2014). The unburnt area is characterized by Austrocedrus chilensis and Nothofagus spp. with endemic herbaceous associations, Maytenus boaria, Schinus patagonicus, Embothrium coccineum, Lomatia hirsuta, Austrocedrus chilensis, Ovidia andina and the burnt forest area, in addition to the lenga (N. pumilio), is composed of other species: Osmorhiza chilensis, Berberis microphylla, Berberis serratodentata, Poa pratensis, Acaena ovalifolia, Ribes cucullatum, Ribes magellanicum, Phacelia secunda, and Calceolaria biflora (Silva et al., 2017).

The samples were taken 1 year after the fire in both cases (in 2009 and in 2016). Burnt and unburnt forest areas were selected using satellite images (sensor MODIS satellite Aqua) and processed using the open source software QGIS 3.4.4. The selected burnt sites presented a high severity of fire impact (> 50% of the subcanopy trees killed or damaged; high charring and some crown damage on canopy trees, but > 50% killed), according to the classification proposed by Mutch and Swetman (1995). Soil invertebrates were sampled using a 10 cm diameter stainless steel core, and each sediment core sample was taken at a depth of 10 cm (the study included a total of 80 soil samples). The samples were taken from the burnt area and from a relict area in the control “unburnt” part, that was not affected by the fire. The samples were repeated in all 4 seasons of both years (2009 and 2016).

The samples were brought to the laboratory, where the mesofauna was extracted with Berlese-Tullgren funnels for 12 days, collecting the fauna in bottles with 70% alcohol. Then, specimens were sorted, counted, and identified to species-level under a microscope (LEICA ICC50 HD) using general and regional keys (Balogh & Balogh, 1988, 1990; Balogh & Csiszár, 1963; Hammer, 1958, 1961, 1962a, b), and the recent catalogue published by Fredes (2018), in which a total of 398 species are listed. Regarding the systematics, the criteria of Schatz (2011) and Fredes (2018) were followed and the biogeographical distribution of species, the criteria of Subías (2004 and updated in 2018) and Fredes (2018) were followed. Species identified as “sp.” and “aff.” were only included in Table 1. The “aff.” term refers to species with morphological deviations, but which are probably not the same species. Taxon authors are not given in the reference list.

Results

A total of 43 species/morphospecies were found. Ten species were new records for Chubut province and 3 to Argentina (Table 1). Thirty-two species are listed below, along with the material examined: number of specimens collected (in parentheses), records in Argentina, and comments. Eleven morphospecies listed in Table 1, identified with “sp.” and “aff.” were not included in the list.

Brachychthoniidae Thor, 1934

Liochthonius van der Hammen, 1959

Liochthonius fimbriatissimus (Hammer, 1958)

Material examined: unburnt (3) and burnt (2).

Records in Argentina: Chubut, Mendoza, Río Negro, Santa Cruz, Tierra del Fuego (Fredes, 2018).

Comments: the distribution of the species is Neotropical (Argentina, Chile), Australian, and Subantarctic (Subías, 2004, update 2018).

Sellnickochthonius Krivolutsky, 1964

Sellnickochthonius elsosneadensis (Hammer, 1958)

Material examined: unburnt (1) and burnt (2).

Records in Argentina: Buenos Aires, Chubut, Mendoza, Río Negro (Fredes, 2018).

Comments: the distribution of the species is semi-cosmopolitan (Subías, 2004, update 2018).

Trichthoniidae Lee, 1982

Trichthonius Hammer, 1961

Trichthonius pulcherrimus (Hammer, 1958)

Material examined: unburnt (2).

Records in Argentina: Buenos Aires, Chubut, Mendoza, Río Negro (Fredes, 2018).

Comments: the distribution of the species is Neotropical (Argentina, Bolivia, Chile and Peru) and Australian (Australia) (Subías, 2004, update 2018).

Table 1

Oribatid mites from the Patagonian forest (Chubut province, Argentina), according to burnt and not burnt (*First record for Chubut and **First record for Argentina)

|

Oribatid species/morphospecies |

UNBURNT |

BURNT |

|

Acaronychidae |

||

|

Stomacarus sp. |

1 |

|

|

Brachychthoniidae |

||

|

Liochthonius (Liochthonius) fimbriatissimus |

3 |

2 |

|

Sellnickochthonius elsosneadensis |

1 |

2 |

|

Cosmochthoniidae |

||

|

Trichthonius pulcherrimus |

2 |

|

|

Euphthiracaridae |

||

|

Acrotritia parareticulata ** |

2 |

|

|

Phthiracaridae |

||

|

Phtiracaridae sp. |

1 |

|

|

Crotoniidae |

||

|

Camisia (Camisia) australis * |

1 |

|

|

Tyrphonothrus |

||

|

Tyrphonothrus (Tyrphonothrus) latus ** |

1 |

|

|

Nothridae |

||

|

Nothrus peruensis* |

1 |

1 |

|

Nothrus sp. 1 |

14 |

|

|

Nothrus sp. 2 |

1 |

|

|

Pheroliodidae |

||

|

Pheroliodes roblensis |

11 |

|

|

Caleremaeidae |

||

|

Anderemaeus magellanis |

2 |

1 |

|

Nodocepheidae |

||

|

Nodocepheus dentatus |

1 |

|

|

Carabodidae |

||

|

Carabodes sp. |

1 |

|

|

Autognetidae |

||

|

Austrogneta multipilosa |

1 |

|

|

Austroppia crozetensis |

1 |

5 |

|

Oppiidae |

||

|

Brachioppiella (Gressittoppia) pepitensis |

2 |

|

|

Table 1 Continued |

||

|

Oribatid species/morphospecies |

UNBURNT |

BURNT |

|

Brachioppiella (Brachioppiella) periculosa * |

2 |

|

|

Brachioppiella (Gressittoppia) peullaensis * |

1 |

|

|

Lanceoppia (Lanceoppia) intermedia |

19 |

|

|

Lanceoppia (Lanceoppia) maior * |

2 |

3 |

|

Lanceoppia (Lancelalmoppia) sp. |

2 |

4 |

|

Lanceoppia (Lancelalmoppia) kovacsi |

2 |

|

|

Membranoppia (Membranoppia) tuxeni |

4 |

|

|

Microppia minus |

1 |

|

|

Lanceoppia (Lancelalmoppia) nodosa * |

1 |

1 |

|

Lanceoppia (Bicristoppia) bicristata * |

1 |

2 |

|

Membranoppia argentinensis |

8 |

2 |

|

Oppiella nova |

14 |

17 |

|

Paroppia patagonica |

4 |

2 |

|

Oxyoppia (Oxyoppiella) suramericana |

2 |

6 |

|

Ramusella (Insculptoppia) sp. |

1 |

|

|

Similoppia (Reductoppia) sp. |

2 |

|

|

Suctobelbidae |

||

|

Suctobelbella sp. |

1 |

|

|

Tectocepheidae |

||

|

Tectocepheus velatus |

22 |

|

|

Cymbaeremaeidae |

||

|

Scapheremaeus ornatus * |

1 |

|

|

Scutoverticidae |

||

|

Scutovertex sp. |

1 |

|

|

Tegoribatidae |

||

|

Physobates spinipes * |

4 |

|

|

Lauroppia fallax ** |

1 |

|

|

Scheloribatidae |

||

|

Fijibates aff. rostratus |

11 |

|

|

Oribatellidae |

||

|

Cuspidozetes armatus * |

3 |

Euphthiracaridae Jacot, 1930

Acrotritia Jacot, 1923

Acrotritia parareticulata (Niedbała, 2002)

Material examined: unburnt (2).

Records in Argentina: first record (Chubut province).

Comments: the species was originally described in Canada as Rhysotritia parareticulata by Niedbała (2002), who found 21 specimens under wet moss in Cedar Grove, Ontario.

Crotoniidae Thorell, 1876

Camisia Heyden, 1826

Camisia australis Hammer, 1958

Material examined: unburnt (1).

Records in Argentina: Mendoza, Rio Negro (Fredes, 2018).

Comments: the distribution of the species is Neotropical (Argentina, Chile, Mexico, and Peru) and Subantarctic (Argentina) (Subías, 2004, update 2018). It is the first record for the province of Chubut.

Malaconothridae Berlese, 1916

Tyrphonothrus Knülle, 1957

Tyrphonothrus (Tyrphonothrus) Knülle, 1957

Tyrphonothrus (Tyrphonotrus) latus (Hammer, 1962)

Material examined: unburnt (1).

Records in Argentina: first records for Argentina.

Comments: recorded distribution in Chile (Subías, 2004, update 2018). It is the first record for Argentina.

Nothridae Berlese, 1896

Nothrus Koch, 1836

Nothrus peruensis Hammer, 1961

Material examined: unburnt (1) and burnt (1).

Records in Argentina: Buenos Aires, Río Negro, Tierra del Fuego (Fredes, 2018).

Comments: the distribution of the species is Neotropical (Argentina, Chile, Mexico, and Peru) and Subantarctic (Argentina) (Subías, 2004, update 2018). It is the first record for the province of Chubut.

Pheroliodidae Paschoal, 1987

Pheroliodes Grandjean, 1931

Pheroliodes roblensis Covarrubias, 1968

Material examined: unburnt (11).

Records in Argentina: Chubut (Fredes, 2018).

Comments: the distribution of the species is Neotropical austral (Argentina, Chile) (Subías, 2004, update 2018).

Anderemaeidae Balogh, 1972

Anderemaeus Hammer, 1958

Anderemaeus magellanis Hammer, 1962

Material examined: unburnt (2).

Records in Argentina: Río Negro, Tierra del Fuego (Fredes, 2018), and Chubut (Manzo et al., 2019).

Comments: the distribution of the species is Neotropical austral (Argentina, Chile) (Subías, 2004, update 2018).

Nodocepheidae Piffl, 1972

Nodocepheus Hammer, 1958

Nodocepheus dentatus Hammer, 1958

Material examined: unburnt (1).

Records in Argentina: Mendoza, Rio Negro, Chubut, Subantarctic region (Fredes, 2018).

Comments: the distribution of species is Neotropical (Argentina, Chile, Ecuador), Oriental (Vietnam), and Subantarctic (Argentina) (Subías, 2004, update 2018).

Autognetidae Grandjean, 1960

Austrogneta Balogh & Csiszár, 1963

Austrogneta multipilosa Balogh & Csiszár, 1963

Material examined: unburnt (2) and burnt (1).

Records in Argentina: Buenos Aires, Río Negro (Fredes, 2018).

Comments: the distribution of the species is Neotropical (Argentina, Peru) and Australian (Australia, New Zealand) (Subías, 2004, update 2018).

Austroppia Balogh, 1983

Austroppia crozetensis (Richters, 1908)

Material examined: unburnt (1) and burnt (5).

Records in Argentina: Subantarctic, Chubut, Tierra del Fuego (Fredes, 2018).

Comments: the distribution of the species is Antarctic, Australian, Neotropical austral (Argentina, Chile), and Subantarctic (Subías, 2004, update 2018).

Oppiidae Sellnick, 1937

Brachioppiella (Brachioppiella) Hammer, 1962

Brachioppiella (Brachioppiella) periculosa Hammer, 1962

Material examined: unburnt (2).

Records in Argentina: Chubut, Río Negro (Fredes, 2018).

Comments: the distribution of the species is Neotropical (Argentina, Cuba) (Subías, 2004, update 2018).

Brachioppiella (Gressittoppia) Balogh, 1983

Brachioppiella (Gressittoppia) pepitensis (Hammer, 1962)

Material examined: unburnt (2).

Records in Argentina: Chubut, Río Negro (Fredes, 2018).

Comments: the distribution of the species is Neotropical austral (Argentina, Chile) (Subías, 2004, update 2018).

Brachioppiella (Gressittoppia) peullaensis Hammer, 1962

Material examined: unburnt (1).

Records in Argentina: Río Negro (Fredes, 2018).

Comments: the distribution of the species is Neotropical austral (Argentina, Chile) (Subías, 2004, update 2018). It is the first record for the province of Chubut.

Graptoppia Balogh, 1983

Graptoppia angusta (Hammer, 1962)

Material examined: unburnt (2).

Records in Argentina: Chubut, Rio Negro, Tierra del Fuego (Fredes, 2018).

Comments: the distribution of the species is Neotropical (Argentina, Peru) (Subías, 2004, update 2018).

Lanceoppia (Lanceoppia) intermedia (Hammer, 1962)

Material examined: unburnt (19).

Records in Argentina: Chubut, Río Negro, Tierra del Fuego, Subantarctic (Fredes, 2018).

Comments: the distribution of the species is Neotropical austral (Argentina, Chile) and Subantarctic (Argentina), and Antarctic (Subías, 2004, update 2018).

Globoppia Hammer, 1962

Lanceoppia (Lanceoppia) maior (Hammer, 1962)

Material examined: unburnt (2) and burnt (3).

Records in Argentina: Río Negro, Santa Cruz, Tierra del Fuego, Subantarctic region (Fredes, 2018).

Comments: the distribution of the species is Neotropical austral (Argentina, Chile) and Subantarctic (Argentina) (Subías, 2004, update 2018). It is the first record for the province of Chubut.

Lanceoppia (Bicristoppia) Subías, 1989

Lanceoppia (Bicristoppia) bicristata (Hammer, 1962)

Material examined: unburnt (1) and burnt (2).

Records in Argentina: Río Negro (Fredes, 2018)

Comments: the distribution of the species is in Argentina (Subías, 2004, update 2018). It is the first record for the province of Chubut.

Lanceoppia (Lanceoppia) Hammer, 1962

Lanceoppia (Lancelalmoppia) kovacsi (Balogh & Csiszár, 1963)

Material examined: unburnt (2).

Records in Argentina: Chubut, Río Negro (Fredes, 2018).

Comments: the distribution of the species is Neotropical (Argentina) (Subías, 2004, update 2018).

Lanceoppia (Lancelalmoppia) Subías, 1989

Lanceoppia (Lancelalmoppia) nodosa (Hammer, 1958)

Material examined: unburnt (1) and burnt (1).

Records in Argentina: Buenos Aires, Mendoza (Fredes, 2018)

Comments: the distribution of the species is Neotropical (Argentina) and Oriental (India) (Subías, 2004, update 2018). It is the first record for the province of Chubut.

Membranoppia Hammer, 1968

Membranoppia argentinensis (Balogh & Csiszár, 1963)

Material examined: unburnt (8) and burnt (2).

Records in Argentina: Chubut, Rio Negro, Tierra del Fuego (Fredes, 2018).

Comments: the distribution of the species is Neotropical (Argentina, Chile) (Subías, 2004, update 2018).

Membranoppia (Membranoppia) Hammer, 1968

Membranoppia (Membranoppia) tuxeni (Hammer, 1968)

Material examined: burnt (4).

Records in Argentina: Chubut (Ruiz, 2018).

Comments: the distribution of the species is Neotropical, New Zealand, and India (Subías, 2004, update 2018).

Microppia balogh, 1983

Microppia minus (Paoli, 1908)

Material examined: unburnt (1).

Records in Argentina: Buenos Aires, Chubut, Misiones, Río Negro (Fredes, 2018). Comments: the distribution of the species is cosmopolitan (Subías, 2004, update 2018). It is fire tolerant (Migliorini et al., 2004)

Oppiella Jacot, 1937

Oppiella nova (Oudemans, 1902)

Material examined: unburnt (14) and burnt (17).

Records in Argentina: Buenos Aires, Chubut, Río Negro (Fredes, 2018).

Comments: the distribution of the species is cosmopolitan (Subías, 2004, update 2018). It is fire tolerant (Webb, 1994)

Oxyoppia (Oxyoppiella) Subias & Rodriguez, 1986

Oxyoppia (Oxyoppiella) suramericana (Hammer, 1958)

Material examined: unburnt (2) and burnt (6).

Records in Argentina: Buenos Aires, Chubut, Mendoza, Misiones, Santa Cruz, Rio Negro (Fredes, 2018).

Comments: the distribution of the species is Neotropical, Australian, and Oriental (Subías, 2004, update 2018).

Paroppia Hammer, 1968

Paroppia patagonica Kun, 2012

Material examined: unburnt (4) and burnt (2).

Records in Argentina: Rio Negro (Fredes, 2018)

Comments: the distribution of the species is in Argentina (Subías, 2004, update 2018).

Tectocepheidae Grandjean, 1954

Tectocepheus Berlese, 1896

Tectocepheus velatus (Michael, 1880)

Material examined: unburnt (22).

Records in Argentina: Buenos Aires, Chubut, Entre Ríos, Misiones, Río Negro, subantarctic region (Fredes, 2018).

Comments: the distribution of this species is cosmopolitan (Subías, 2004, update 2018). It is the most heat–tolerant species within Oribatida (Malmström, 2008).

Cymbaeremaeidae Sellnick, 1928

Scapheremaeus Berlese, 1910

Scapheremaeus ornatus Balogh & Mahunka, 1968

Material examined: burnt (1).

Records in Argentina: Córdoba (Fredes, 2018).

Comments: the distribution of the species is Neotropical (Argentina, Mexico) (Subías, 2004, update 2018). It is the first record for the province of Chubut.

Tegoribatidae Grandjean, 1954

Physobates Hammer, 1962

Physobates spinipes Hammer, 1962

Material examined: unburnt (4).

Records in Argentina: Buenos Aires, Río Negro (Fredes, 2018).

Comments: the distribution of the species is Neotropical (Argentina, Chile) (Subías, 2004, update 2018). It is the first record for the province of Chubut.

Lauroppia Subías & Mínguez, 1986

Lauroppia fallax (Paoli, 1908)

Material examined: burnt (1).

Records in Argentina: first records for Argentina.

Comments: the distribution of the species is semi-cosmopolitan (Holarctic: western Palearctic, India: Uttar Pradesh, New Zealand, Chile). It is the first record for Argentina.

Oribatellidae Jacot, 1925

Cuspidozetes Hammer, 1962

Cuspidozetes armatus Hammer, 1962

Material examined: unburnt (3).

Records in Argentina: Río Negro (Fredes, 2018)

Comments: the distribution of the species is Neotropical (Argentina, Mexico) (Subías, 2004, update 2018). It is the first record for the province of Chubut.

Discussion

Of the new records from Argentina, there are 2 previously cited from Chile Tyrphonothrus (Tyrphonotrus) latus and Lauroppia fallax (Subías, 2004, update 2018). More than 60% of listed species are shared with Chile. Such a large proportion would possibly be expected due to the proximity of the sampling sites to the Chile-Argentina border. These species include: Trichthonius pulcherrimus, Anderemaeus magellanis, Pheroliodes roblensis, Brachiopiella (Gressittoppia) pepitensis, Lanceoppia (Lanceoppia) intermedia, Lanceoppia (Lanceoppia) maior, Lanceoppia (Lanceoppia) kovacsi, Graptoppia (Stenoppia) angusta, Nodocepheus dentatus (Subías, 2004, update 2018). While Acrotritia parareticulata, which the present study cites as a new record for Argentina, has previously been described in Canada, other species from the same genera have also been cited in studies from both Canada and Argentina, e.g., Acrotritia ardua (Koch, 1841). Furthermore, other, distinct genera have also been documented in studies from both countries. These include: Banksinoma spinifera (Hammer, 1952), Verachthonius montanus (Hammer 1952), Tectoribates borealis Behan-Pelletier & Walters, 2013 (Subías, 2004, update 2018), all of which are species endemic to the Americas.

Of the new records from Chubut, more than 80% have previously been found in central and southern Argentina, which is no doubt a testament to the biogeographical relationships between these different regions (Fredes & Martínez, 2008).

Exactly one quarter of the species found were shared with New Zealand. These include Lauroppia fallax, Austrogneta multipilosa, and Membranoppia (M.) tuxeni. Such a high proportion could be expected and explained by the fact that the 2 regions were directly connected by land during the Paleozoic Era. This has been cited by several authors (e.g., Kun et al., 2010; Ruiz et al., 2018). In addition, both regions shared the Nothofagus spp. distribution, which might point towards a specific relationship between Nothofagus spp. and Oribatid mite species.

Of the identified species, Sellnickochthonius elsosneadensis, Oppiella nova, Microppia minus, and Tectocepheus velatus have a cosmopolitan or semi-cosmopolitan distribution (Subías, 2004, update 2018). Sellnickochthonius elsosneadensis was originally described in Mendoza, Argentina, on moist moss cushions between stiff Juncus (Hammer, 1958). Kun et al. (2010) found it under the forest soil of Nothofagus antarctica, Ruiz et al. (2015) found it in Chubut under the forest soil of Nothofagus pumilio, and Fredes (2016) under patches of tala (Celtis erhenbergiana). Oppiella nova, Microppia minus, and Tectocepheus velatus are euryoecious species, found in all types of soils and climates, and are resistant to drought conditions (Lindberg & Bengtsson, 2005), pesticides (Prinzing et al., 2002) and fires (Webb, 1994). Their adaptive success is attributed, among other things, to a generalist diet and parthenogenetic reproduction (Norton & Palmer, 1991; Siepel, 1994). Tectocepheus velatus is characterized by its dietary preference for mosses (Murvaridze et al., 2008), and requires sites with high humidity and organic matter, conditions that are not presented by a burnt site after a year. Malmström et al. (2008) did not record any recovery in oribatid mite communities 2 years after an incidence of fire.

Acknowledgments

We specially thank Gwion Elis-Williams for the English language revision. To Camilo Rotela for his assistance in the work and the “Parque Nacional los Alerces”. To anonymous reviewers from RMB for their important contribution to this manuscript.

References

Balogh, P., & Balogh, J. (1988). The soil mites of the World, Vol. 2. Oribatid mites of the Neotropical Region I. Budapest: Hungarian Magnolia Press, Natural History Museum.

Balogh, P., & Balogh, J. (1990). The soil mites of the World, Vol. 3. Oribatid mites of the Neotropical Region II. Budapest: Hungarian Magnolia Press, Natural History Museum.

Balogh, J., & Csiszár, J. (1963). The zoological results of Gy. Topal’s collecting in south Argentina. 5. Oribatei (Acarina). Annales Historico-naturales Musei Nationalis Hungarici, 55, 463–485.

Bowman, D. M., Balch, J., Artaxo, P., Bond, W. J., Cochrane, M. A., D’antonio, C. M. et al. (2011). The human dimension of fire regimes on Earth. Journal of Biogeography, 38, 2223–2236. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02595.x

Cabrera, A. L., & Willink, A. (1980). Biogeografía de América Latina Monografía, 13. Serie Biología, 69–75.

Castillo-Soto, M. (2006). Incendios forestales y medioambiente: una síntesis global. Informe técnico. Santiago: Laboratorio de incendios forestales, Universidad Nacional de Chile.

Donoso, Z. (1997). El bosque y su medio ambiente. Ecología Forestal, 369, 429–435.

Fredes, N. A. (2016). Estudio de la comunidad de oribátidos (Acari: Oribatida) en dos parches de tala (Celtis ehrenbergiana) del sudeste bonaerense. Ecología Austral, 26, 275–285.

Fredes, N. A. (2018). Catalogue of oribatid mites (Acari: Oribatida) from Argentina. Zootaxa, 4406, 1–190. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4406.1.1

Fredes, N. A., & Martínez, P. A. (2008). Nuevos registros de ácaros oribátidos (Acari: Oribatida) para la Argentina. Revista de la Sociedad Entomológica Argentina, 67, 171–174.

Hammer, M. (1958) Investigations on the oribatid fauna of the Andes Mountains I. The Argentine and Bolivia. Biologiske Skrifter udgivet af Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, 10, 1–262.

Hammer, M. (1961). Investigations on the oribatid fauna of the Andes Mountains II, Peru. Biologiske Skrifter udgivet af Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, 13, 1–200.

Hammer, M. (1962a). Investigations on the oribatid fauna of the Andes Mountains III, Chile. Biologiske Skrifter udgivet af Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, 13, 1–96.

Hammer, M. (1962b). Investigations on the oribatid fauna of the Andes Mountains, IV, Patagonia. Biologiske Skrifter udgivet af Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, 13, 1–35.

Harnett, D. C. (1991). Effects of fire in tallgrass prairie on growth and reproduction of prairie coneflower (Ratibibda columnifera: Asteraceae). American Journal of Botany, 78, 429 –435.

Heyward, F., & Tissot, A. N. (1936). Some changes in the soil fauna associated with forest fires in the longleaf pine region. Ecology, 17, 659–666.

Hobbs, R. J., & Atkins, I. (1990). Fire-related dynamics of a Banksia woodland in southwestern Australia. Australian Journal of Botany, 38, 97–110.

Huhta, V., Karppinen, E., Nurminen, M., & Valpas, A. (1967). Effect of silvicultural practices upon arthropod, annelid and nematode populations in coniferous forest soil. Annales Zoologici Fennici, 4, 87–145.

Jonson, E. A. (1992). Fire and vegetation dynamics: studies from the North American boreal forest. Cambridge University Press.

Knicker, H. (2007). How does fire affect the nature and stability of soil organic nitrogen and carbon? A review. Biogeochemistry, 85, 91–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-007-9104-4

Kun, M. E., Martínez, P. A., & González, A. (2010). Oribatid mites (Acari: Oribatida) from Austrocedrus chilensis and Nothofagus forests of northwestern Patagonia (Argentina). Zootaxa, 2548, 22–42. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2548.1.2

Liacos, L. G. (1977). Fire and fuel management in pine forest and evergreen brushland ecosystems in Greece. In H. A. Mooney, & C. E. Conrad (Technical coordinators), Proceedings of the Symposium on the Environmental Consequences of Fire and fuel Management in Mediterranean Ecosystem5s. USDA, Forest Service General Technical Report WO, 3, 289–298.

Lindberg, N., & Bengtsson, J. (2005). Population responses of oribatid mites and collembolans after drought. Applied Soil Ecology, 28, 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2004.07.003

Malmström, A. (2008) Temperature tolerance in soil microarthropods: simulation of forest-fire heating in the laboratory. Pedobiologia, 51, 419– 426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedobi.2008.01.001

Malmström, A. (2010). The importance of measuring fire severity- Evidence from microarthropods studies. Forest Ecology and Management, 260, 6270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2010.04.001

Malmström, A., Persson T., & Ahlström, K. (2008). Effects of fire intensity on survival and recovery of soil microarthropods after a clearcut burning. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 38, 2465–2475. https://doi.org/10.1139/X08-094

Manzo, R. M., & Rizzuto, S. (2020) Ácaros oribátidos (Acari: Oribatida) asociados a la descomposición de la madera de Nothofagus pumilio en la provincia de Chubut. Revista de la Sociedad Entomológica Argentina, 79, 14–19. https://doi.org/10.25085/rsea.790203

Manzo, R. M., Rizzuto, S., Ruiz, E. V., & Martínez, P. A. (2019) Oribatid mites (Acari: Oribatida) from the Patagonian steppe, Argentina. Zootaxa, 4686, 241–252. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4686.2.4

Migliorini, M., Pigino, G., Avanzati, A. M., Salomone, N., & Bernini, F. (2004). Experimental fires in a Mediterranean environment: effects on oribatid mite communities. Phytophaga, XIV, 271–277.

Murvaridze, M., Arabuli, T., Kvavadzeand, E. R., & Mundadze, M. (2008). The effect of fire disturbance on oribatid mite communities. In Integrative Acarology: Proceedings of the 6th European Congress, 2008, Montpellier, 216–221.

Mutch, L. S., & Swetnam, T. W. (1995). Effects of fire severity and climate on ring-width growth of giant Sequoia after burning. In J. K. Brown, R. W. Mutch, C. W. Spoon, R. H. Wakimoto (Eds.), Proceedings Symposium on fire in wilderness and park management. Missoula, March 30 – April 01, 1993. Report INT-GTR-320. Missoula, USA. USDA Forest Service. Intermountain Research Station, 241–246.

N’Dri, J. K., N’Da, R. A. G., Seka, F. A., Pokou, P. K., Tondoh, J. E., Lagerlöf, J. et al. (2017). Patterns of soil mite diversity in Lamto savannah (Côte d’Ivoire) submitted at different fire regimes. Acarologia, 57, 823–833. https://doi.org/10.24349/acarologia/20174196

Norton, R. A., & Behan-Pelletier, V. M. (2009) Suborder Oribatida. In G.W. Krantz, & D. E. Walter (Eds.), A manual of Acarology, 3rd Edition (pp. 430–564). Lubbock, Texas: Texas Tech University Press.

Norton, R. A., & Palmer, S. C. (1991). The distribution, mechanisms and evolutionary significance of parthenogenesis in oribatid mites. In Schuster, R., & Murphy, P.W. (Eds.), The Acari – reproduction, development and life-history strategies (pp. 107–136). London/New York: Chapman and Hall. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-3102-5_7

Pearse, A.S. (1943). Effects of burning-over and raking-off litter on certain soil animals in the Duke forest. American Midland Naturalist, 29, 406–429.

Prinzing, A., Kretzler, S., Badejo, A., & Beck, L. (2002). Traits of oribatid mite species that tolerate habitat disturbance due to pesticide application. Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 34, 1655–1661. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0038-0717(02)00149-9

Ruiz, E. V., Rizzuto, S., & Martínez, P. A. (2015). Primeros registros de ácaros oribátidos (Acari: Oribatida) de bosques de Nothofagus pumilio en la región Patagónica, Chubut, Argentina. Revista de la Sociedad Entomológica Argentina, 74, 69–73.

Ruiz, E. V., Rizzuto, S., & Martínez, P. A. (2018). New records of oribatid mites (Acari, Oribatida) from Argentina. Zootaxa, 4370, 194–200. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4370.2.8

Schatz, H., Behan-Palletier, V. M., O’Connor, B. M., & Norton, R. A. (2011). Suborder Oribatida van der Hammen, 1968. In Z. Q. Zhang (Ed.), Animal biodiversity: an outline of higher-level classification and survey of taxonomic richness. Zootaxa, 3148, 141–148. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3148.1.26

Siepel, H. (1994). Life-history tactics of soil microarthropods. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 18, 263–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00570628

Silva, P. V., Quinteros, C. P., Greslebin, A. G., Bava, J. O., & Defossé, G. E. (2017). Characterization of Nothofagus pumilio (lenga) understory in managed and unmanaged forests of Central Patagonia, Argentina. Forest Science, 63, 173–183. https://doi.org/10.5849/forsci.15-156

Soil Survey Staff (2014). Claves para la taxonomía de suelos. Departamento de Agricultura de los Estados Unidos. 12 Ed. Servicio de Conservación de Recursos Naturales.

Subías, L. S. (2004). Listado sistemático, sinonímico y biogeográfico de los ácaros oribátidos (Acariformes, Oribatida) del mundo (1758-2002). Graellsia, 1982, 1–570. https://doi.org/10.3989/graellsia.2004.v60.iExtra.218

Veblen, T. T., Kitzberger, T., Raffaele, E., Mermoz, M., González, M. E., Sibold, J. S. et al. (2009). The historical range of variability of fires in the Andean-Patagonian Nothofagus forest region. International Journal of Wildland Fire, 17, 724–741. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF07152

Walter, D. E., & Proctor, H. C. (2013) Mites: ecology, evolution and behaviour. Life at a microscale. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7164-2

Webb, N. R. (1994). Post-fire succession of cryptostigmatic mites (Acari, Cryptostigmata) in a Calluna-heathland soil. Pedobiologia, 38, 138–145.

Zaitsev, A. S., Gongalsky, K. B., Malmström, A., Persson, T., & Bengtsson, J. (2016). Why are forest fires generally neglected in soil fauna research? A mini-review. Applied Soil Ecology, 98, 261–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2015.10.012