Giovani Hernández-Canchola a, b, *, Livia León-Paniagua c, Jacob A. Esselstyn a, d

a Louisiana State University, Museum of Natural Science, 119 Foster Hall, 70803 Baton Rouge, LA, USA

b Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Ecología, Departamento de Ecología de la Biodiversidad, Circuito Exterior s/n, Cuidad Universitaria, Coyoacán, 04510 Ciudad de México, Mexico

c Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Facultad de Ciencias, Departamento de Biología Evolutiva, Colección de Mamíferos – Museo de Zoología “Alfonso L. Herrera”, Circuito Exterior s/n, Cuidad Universitaria, Coyoacán, 04510 Ciudad de México, Mexico

d Louisiana State University, Department of Biological Sciences, 202 Life Sciences Building, 70803 Baton Rouge, LA, USA

*Corresponding author: giovani@ciencias.unam.mx (G. Hernández-Canchola)

Received: 1 November 2020; accepted: 16 August 2021

Abstract

Although deer mice (Peromyscus spp.) are among the most studied small mammals, their species diversity and phylogenetic relationships remain unclear. The lack of taxonomic clarity is mainly due to a conservative morphology and because some taxa are rare, have restricted distributions, or are poorly sampled. One taxon, P. mexicanus, includes southern Mexican subspecies that have not had their systematic placement tested with genetic data. We analyzed the phylogenetic relationships and genetic structure of P. mexicanus populations using sequences of the mitochondrial gene cytochrome b. We inferred that P. mexicanus is paraphyletic, with P. m. teapensis, P. m. tehuantepecus, and P. m. totontepecus more closely related to P. gymnotis than to P. m. mexicanus. This highly divergent clade ranges from northeastern Oaxaca to northern Chiapas, including southern Veracruz, and southern Tabasco. In light of this group’s mitochondrial distinctiveness, cohesive geographic range, and previously reported molecular, biochemical, and morphological differences, we recommend it be treated as P. totontepecus. Our findings demonstrate the need for an improved understanding of the diversity and evolutionary history of these common and abundant members of North American small mammal communities.

Keywords: Teapensis; Tehuantepecus; Totontepecus; Molecular phylogeny; Cytochrome b

© 2022 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license

Relaciones parafiléticas reveladas por ADN mitocondrial en el grupo de especies Peromyscus mexicanus (Rodentia: Cricetidae)

Resumen

Si bien los ratones del género Peromyscus son uno de los grupos de mamíferos mejor estudiados, su diversidad de especies y relaciones filogenéticas aún no son entendidas. Esta falta de claridad taxonómica se debe, principalmente, a su morfología conservada y a que algunos taxones son raros, tienen distribuciones restringidas o han sido poco muestreados. Peromyscus mexicanus incluye subespecies del sur de México que no han sido analizadas utilizando datos genéticos, y nosotros investigamos sus relaciones filogenéticas y estructuración genética usando las secuencias del gen mitocondrial citocromo b. Detectamos que P. mexicanus es parafilético, ya que P. m. teapensis, P. m. tehuantepecus y P. m. totontepecus están más relacionados filogenéticamente con P. gymnotis que con P. m. mexicanus. Este clado, altamente divergente, se distribuye desde el noreste de Oaxaca al norte de Chiapas, incluyendo el sur de Veracruz y el sur de Tabasco. Con base en su distinción mitocondrial, el rango geográfico cohesivo de este clado y la información molecular, bioquímica y morfológica previamente reportada, recomendamos tratarlo como P. totontepecus. Nuestros resultados demuestran la necesidad de mejorar el entendimiento sobre la diversidad e historia evolutiva de estos miembros comunes y abundantes de pequeños mamíferos de Norteamérica.

Palabras clave: Teapensis; Tehuantepecus; Totontepecus; Filogenia molecular; Citocromo b

© 2022 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. Este es un artículo Open Access bajo la licencia CC BY-NC-ND

Introduction

In North and Central America, mice in the genus Peromyscus are among the most frequently encountered species and are considered one of the small mammals better studied in many biological subdisciplines (Bradley et al., 2004, 2007; Sullivan et al., 2017). However, fundamental aspects of their biology, such as their species-level diversity, are still unclear (Bradley et al., 2007; Miller & Engstrom, 2008; Platt et al., 2015; Sullivan et al., 2017). For example, the number of recognized Peromyscus species has shifted recently from 66 (Pardiñas et al., 2017) to 76 (Álvarez-Castañeda et al., 2019; Bradley et al., 2019; Greenbaum et al., 2019; León-Tapia et al., 2020; López-González et al., 2019), and further evidence suggests additional undescribed diversity (Ávila-Valle et al., 2012; Bradley et al., 2017; Castañeda-Rico et al., 2014; Durish et al., 2004; Pérez-Consuegra & Vázquez-Domínguez, 2017). Moreover, Peromyscus is a paraphyletic taxon because other phenotypically distinct genera (Habromys, Megadontomys, Neotomodon, Osgoodomys, and Podomys) are phylogenetically nested within Peromyscus (Bradley et al., 2007; Miller & Engstrom, 2008; Platt et al., 2015; Sullivan et al., 2017). As such, the current taxonomic arrangement of Peromyscus probably provides only a rough approximation of their species diversity and systematics.

Morphometrical, morphological, karyological, and biochemical data were amply used for nearly a century to understand phylogenetic relationships of Peromyscus mice (Carleton, 1980, 1989; Hsu & Arrighi, 1966; Osgood, 1909; Stangl & Baker, 1984), and these early findings were subsequently refined with the use of DNA sequencing (Bradley et al., 2007; Miller & Engstrom, 2008; Platt et al., 2015; Sullivan et al., 2017). Most of these more recent investigations sequenced the mitochondrial gene cytochrome b (cyt-b), which has proven beneficial to clarify phylogenetic relationships between species in Peromyscus and related genera, such as Baiomys, Habromys, Megadontomys, Nelsonia, Neotoma, and Reithrodontomys (Arellano et al., 2005; Bradley et al., 2017, 2019; Hernández-Canchola et al., 2021; Hernández-Canchola & León-Paniagua, 2021; León-Tapia, 2013; Rogers et al., 2007; Vallejo & González-Cózatl, 2012).

Within Peromyscus, species groups have provided valuable taxonomic structure that guide evolutionary studies (Platt et al., 2015). One of the most diverse species groups is the P. mexicanus group (Pérez-Consuegra & Vázquez-Domínguez, 2015, 2017). Originally, it included only 4 species (Osgood, 1909), but several taxa have since been added (Bradley et al., 2007; Carleton, 1989; Pérez-Consuegra & Vázquez-Domínguez, 2015; Rogers & Engstrom, 1992). In later decades, the P. mexicanus group fluctuated in diversity, ranging from 7 to 17 species (Wade, 1999), but the most recent molecular investigations, based on cyt-b, showed that this group includes at least 15 allopatric clades that are morphometrically discernible (Pérez-Consuegra & Vázquez-Domínguez, 2015, 2017). The P. mexicanus species group currently includes P. mexicanus (from San Luis Potosí to Chiapas, in Mexico), P. bakeri (Guatemala), P. carolpattonae (Chiapas and Guatemala), P. gardneri (Guatemala), P. nicaraguae (Honduras and Nicaragua), P. nudipes (Costa Rica), P. grandis (Guatemala), P. guatemalensis (Guatemala), P. gymnotis (Chiapas and Guatemala), P. salvadorensis (El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala), P. tropicalis (Belize and Guatemala), P. zarhynchus (Chiapas), in addition to 3 undescribed clades previously named as “G” (Chiapas), “O” (Guatemala), and “L” (Guatemala and Honduras) (Álvarez-Castañeda et al., 2019; Lorenzo et al., 2016; Pérez-Consuegra & Vázquez-Domínguez, 2015, 2017).

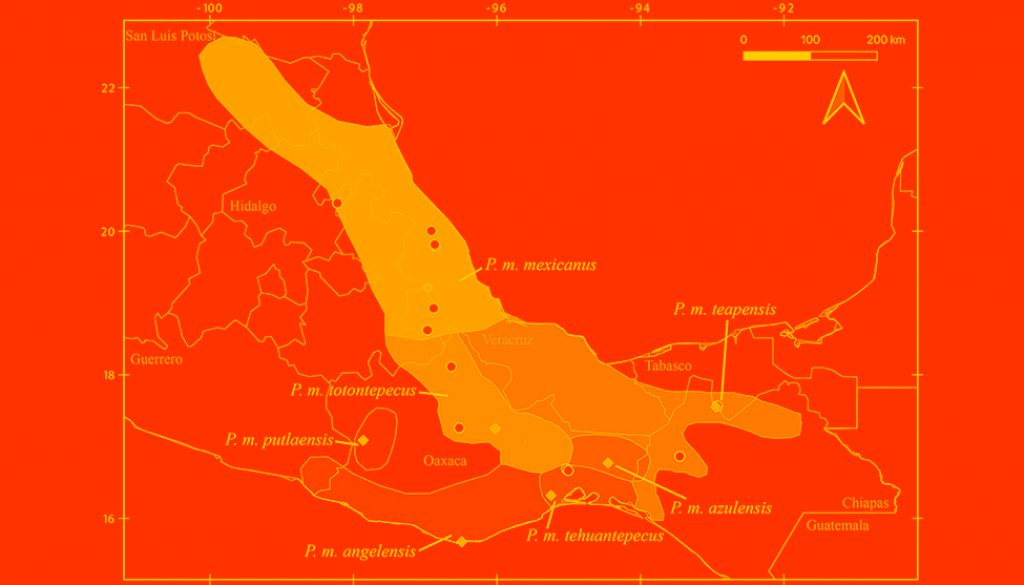

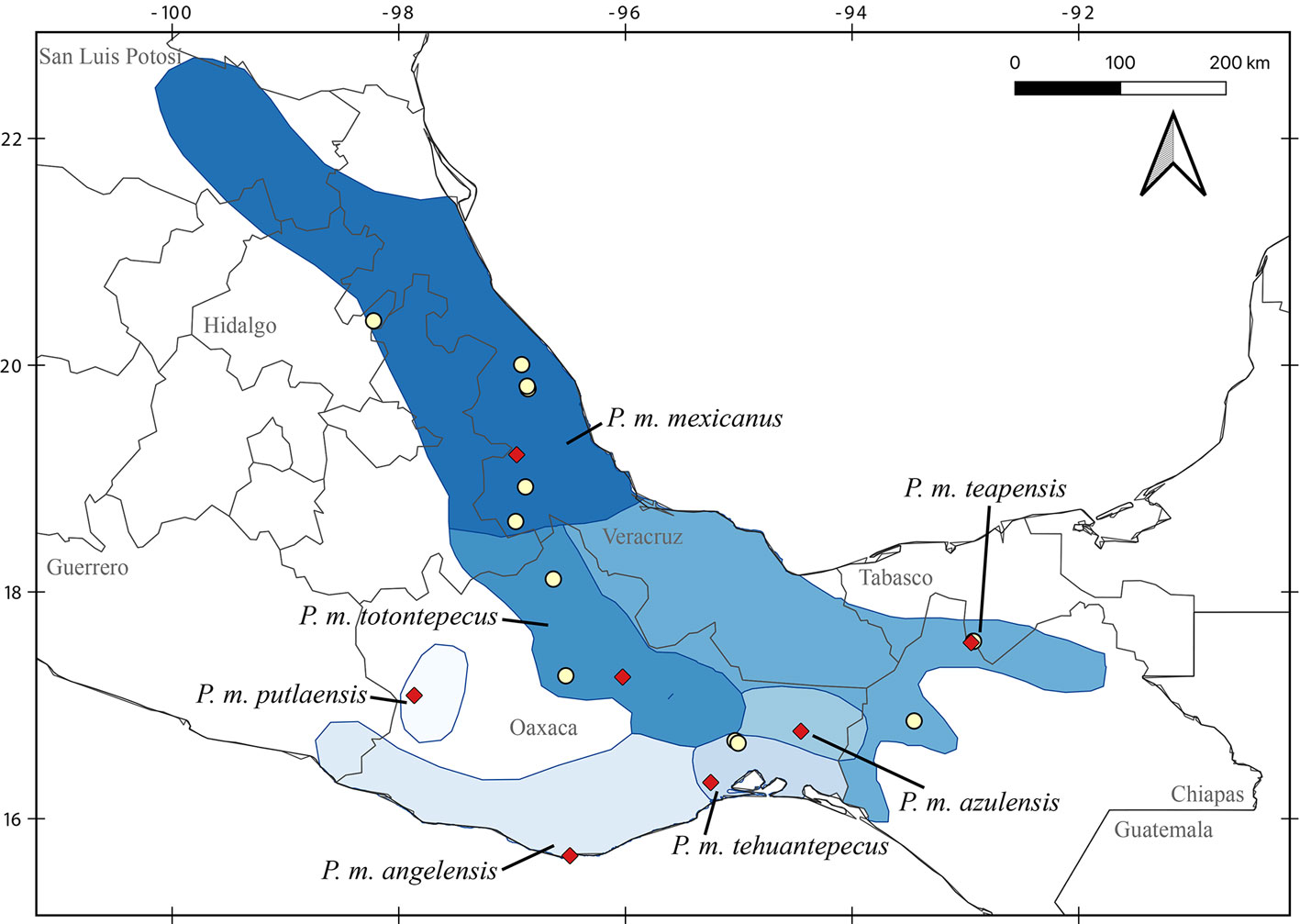

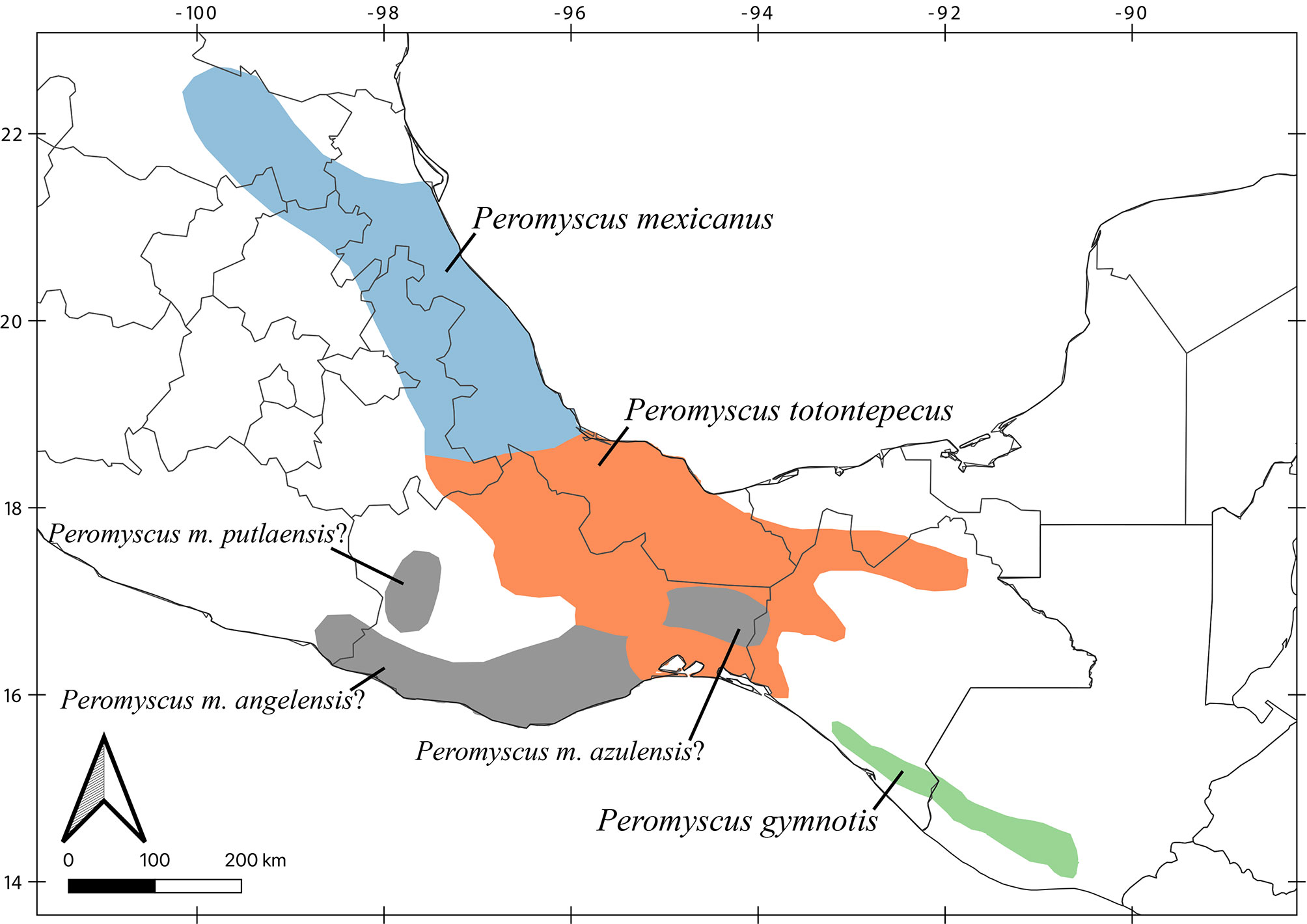

Despite recent advances, discrepancies and information gaps remain. For instance, based on morphological descriptions, Ramírez-Pulido et al. (2005), Trujano-Álvarez and Álvarez-Castañeda (2010), and Pardiñas et al. (2017), recognized 7 subspecies in P. mexicanus (P. m. mexicanus [from San Luis Potosí to Oaxaca], P. m. angelensis [coastal region in southeastern Guerrero and southern Oaxaca], P. m. azulensis [Oaxaca’s mountains at the east of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec], P. m. putlaensis [west-central Oaxaca], P. m. saxatilis [southern Chiapas and Guatemala], P. m. teapensis [southern Veracruz, Tabasco, northern Chiapas], and P. m. totontepecus [northeastern Oaxaca]), but Ramírez-Pulido et al. (2014) also recognized P. m. tehuantepecus (Oaxaca’s lowlands at the south of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec) (Fig. 1). Additionally, recent works showed that the southernmost distribution of P. mexicanus is northern Chiapas (Pérez-Consuegra & Vázquez-Domínguez, 2015, 2017), so that P. m. saxatilis could represent an isolated population (its type locality is in Guatemala), but the names P. nicaraguae, P. salvadorensis, and P. tropicalis were resurrected from synonymy with P. m. saxatilis, when these 3 Central American clades were found to be distant relatives of P. mexicanus (Pérez-Consuegra & Vázquez-Domínguez, 2015), meaning that P. m. saxatilis should no longer be considered a subspecies of P. mexicanus. On the other hand, a research based on cranial morphological variation suggested that P. m. teapensis and P. m. totontepecus could be treated as independent species (Zaragoza-Quintana, 2005), and even though mitochondrial DNA studies showed that P. mexicanus is paraphyletic (Bradley et al., 2007; Rogers & Engstrom, 1992; Wade, 1999), and that P. m. teapensis is closely related to P. gymnotis and not to P. mexicanus (Pérez-Consuegra & Vázquez-Domínguez, 2017), it was relegated to subspecific status within P. mexicanus (Pardiñas et al., 2017; Pérez-Consuegra & Vázquez-Domínguez, 2015, 2017).

Southern Mexico is home to several subspecies of the Mexican endemic deer mouse, Peromyscus mexicanus, that have not been included in previous molecular systematics revisions. Those populations deserve particular attention from systematists because the heterogeneous topography in Southern Mexico has promoted a diverse small mammal fauna in which numerous taxonomic arrangements have been confused (Guevara et al., 2014; Guevara & Cervantes, 2014; León-Paniagua et al., 2007; Vallejo & González-Cózatl, 2012; Woodman & Timm, 1999). Here, we combined previously published genetic data and new mitochondrial DNA sequences from recently collected P. mexicanus from Oaxaca and Tabasco (P. m. teapensis, P. m. tehuantepecus, P. m. totontepecus) (Fig. 1) to assess systematic relationships and to analyze if mitochondrial DNA supports past morphological, molecular and/or taxonomic hypotheses that could clarify some remaining taxonomic issues in the Mexican deer mouse (Bradley et al., 2007; Pérez-Consuegra & Vázquez-Domínguez, 2017; Ramírez-Pulido et al., 2014; Rogers & Engstrom, 1992; Wade, 1999; Zaragoza-Quintana, 2005).

Materials and methods

All samples came from specimens hosted in scientific collections, and no ad hoc fieldwork was performed for this research. Voucher specimens are deposited in the following mammal collections: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Facultad de Ciencias, Mexico City, Mexico (MZFC); Louisiana State University, Museum of Natural Science, Baton Rouge, USA (LSUMZ); University of California, Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, Berkeley, USA (MVZ); and Texas Tech University, Museum of Texas Tech University, Lubbock, USA (TTU) (Appendix). We sequenced specimens referred to Peromyscus mexicanus and used morphological traits defined by Álvarez-Castañeda et al. (2015) to verify their identity. We also followed the original descriptions, and used the geographic origin of samples to identify them at the subspecies level (Goodwin, 1956, 1964; Merriam, 1898; Osgood, 1904). We identified 2 specimens from Veracruz as P. m. mexicanus (LSUMZ 36423, MZFC 11166), 2 specimens from Teapa, Tabasco (type locality of P. m. teapensis) as P. m. teapensis (MZFC-PMM068, MZFC-PMM081), 2 specimens from Nizanda, Oaxaca (Oaxaca’s lowlands at the south of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec) as P. m. tehuantepecus (MZFC 9288, MZFC 9308), and 2 specimens from northeastern Oaxaca as P. m. totontepecus (MZFC 8689, MZFC 14085). The missing subspecies not analyzed in this work were P. m. angelensis, P. m. azulensis, and P. m. putlaensis.

We sequenced these 8 specimens, along with 2 P. carolpattonae from Chiapas (MZFC 9736, MZFC 9737), Mexico; 1 P. gardneri from Huehuetenango, Guatemala (MVZ 223293); 1 Peromyscus “L” (sensu Pérez-Consuegra & Vázquez-Domínguez, 2017) from Santa Rosa, Guatemala (MVZ 235925); 1 Peromyscus “O” (sensu Pérez-Consuegra & Vázquez-Domínguez, 2017) from El Progreso, Guatemala (MVZ 223386); 2 P. nudipes from Cartago and San José, Costa Rica (LSUMZ 28348, LSUMZ 29483); 1 P. salvadorensis from Chalaltenango, El Salvador (MZFC 10917); and 1 P. tropicalis from Izabal, Guatemala (TTU 62079). Additionally, we sequenced 1 P. megalops from Guerrero, Mexico (MZFC 11449), that was used as an outgroup (Bradley et al., 2007).

We extracted whole genomic DNA using a Qiagen DNEasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen, Germantown, Maryland), following the manufacturer’s recommended protocols. Through polymerase chain reaction (PCR), we amplified the complete mitochondrial gene cytochrome b (cyt-b) using the primers MVZ05 (Smith & Patton, 1993) and H15915 (Irwin et al., 1991). Each PCR had a final reaction volume of 13 μL and contained 6.25 μL of GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), 4.75 μL of H20, 0.5 μL of each primer [10μM], and 1 μL of DNA stock. The PCR thermal profile included 2 minutes of initial denaturation at 95 °C, followed by 38 cycles of 30 seconds of denaturation at 95 °C, 30 seconds of annealing at 50 °C, and 1:08 minutes for the extension at 72 °C. We included a 5-minute final extension step at 72 °C. We visualized 3 μL of each PCR product using electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels, stained with SYBR Safe DNA Gel Stain (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). We cleaned each PCR product using 1 μL of a 20% dilution of ExoSAP-IT (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp. Piscataway, NJ, USA) incubated for 30 minutes at 37 °C followed by 15 minutes at 80 °C. Samples were cycle-sequenced using 6.1 μL of H20, 1.5 μL of 5x buffer, 1 μL of 10μM primer, 0.4 μL of ABI PRISM Big Dye v. 3.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), and 1 μL of the cleaned template. The cycle-sequencing profile included 1 minute of initial denaturation at 96 °C, followed by 25 cycles of 10 seconds for denaturation at 96 °C, 5 seconds for annealing at 50 °C, and 4 minutes for the extension at 60 °C. Cycle sequencing products were purified using an EtOH-EDTA precipitation protocol and were read with an ABI 3130xl genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). DNA sequences were edited, aligned, and visually inspected using Mega X (Kumar et al., 2018) and FinchTV 1.4 (Patterson et al., 2004). We added 41 sequences available in GenBank from the P. mexicanus species group (Bradley et al., 2007; Pérez-Consuegra & Vázquez-Domínguez, 2015, 2017) (Appendix).

We used maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) to estimate phylogenetic relationships of the P. mexicanus species group. We selected the best partition (initially divided by codon position) and the best-fit substitution model in PartitionFinder 2 (Lanfear et al., 2016), through an exhaustive search among all available models in MrBayes 3.2 (Ronquist et al., 2012), and using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). We used this result for parameterizing both ML and BI. In IQ-TREE 1.6.12 (Nguyen et al., 2015), we estimated the ML gene tree, and assessed branch support with 1,000 nonparametric bootstraps. In MrBayes 3.2 we used 3 hot chains and 1 cold chain in 2 independent runs of 10 million generations, sampling every 1,000 iterations. We checked for convergence of Metropolis-Coupled Markov Chain Monte Carlo results by examining trace plots and confirming in Tracer 1.7 (Rambaut et al., 2018)that effective sample sizes for all parameters were > 200. The final topology was obtained by calculating a majority rule consensus tree from the posterior, after removing a burn-in of 25%.

To test alternative topologies, we inferred the best tree consistent with a constraint that forced the monophyly of P. m. teapensis, P. m. tehuantepecus, or P. m. totontepecus, and all other P. m. mexicanus samples (i.e., 3 distinct constraints). These were estimated in MrBayes, as described above. To compare the majority rule consensus trees of unconstrained BI and the best trees consistent with the constraint, we used the Shimodaira-Hasegawa test (Shimodaira & Hasegawa, 1999) as implemented in phangorn (Schliep, 2011). We compared the likelihoods of each topology assuming an HKY+I+G substitution model (calculated in PartitionFinder 2) and 10,000 bootstrap replicates. We performed analyses with and without optimizing the rate matrices, gamma distribution, invariable sites, and base frequencies.

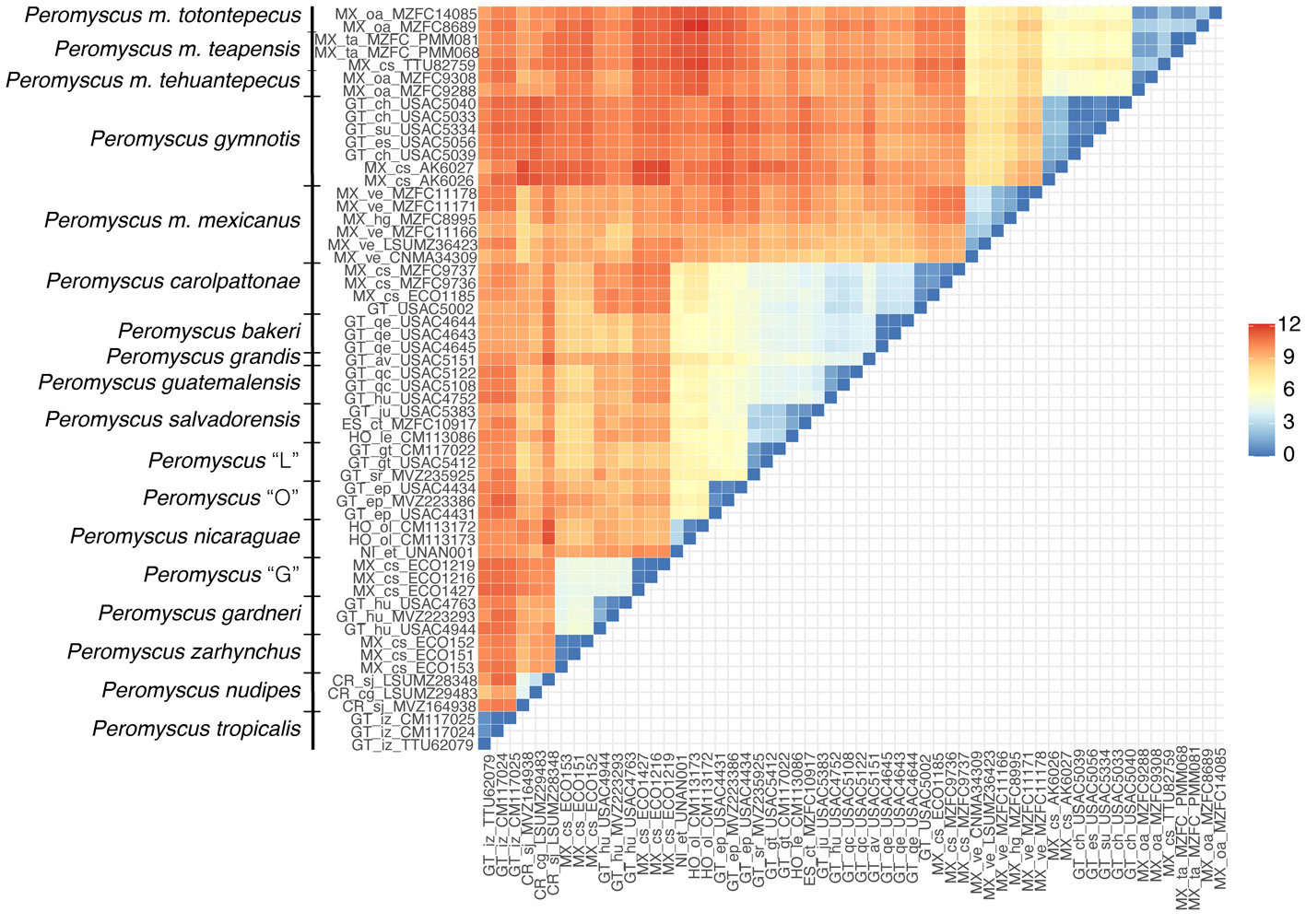

To evaluate levels of differentiation among clades in the P. mexicanus species group, we calculated p-distances in Mega X, using the pairwise deletion option and the Kimura 2-parameter model (Kimura, 1980), and we draw a heat map using the ggplot2 R package (Wickham, 2011). Based on preliminary analyses, we found that some of our samples could represent an independent mitochondrial clade, so we analyzed its levels of genetic structure to understand its distinctness better. Thus, in Arlequin 3.5 (Excoffier & Lischer, 2010), we used an analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) to estimate genetic diversity among clades (FCT), among localities within clades (FSC), and within localities (FST), taking into account the molecular distance between haplotypes (Pérez-Consuegra & Vázquez-Domínguez, 2015). We used the matrix of pairwise differences corrected with the Kimura 2-parameter model and used 10,000 permutations to evaluate the significance of our results (α = 0.05). Finally, to further characterize genetic diversity, we used DnaSP 5.10 (Librado & Rozas, 2009) to calculate the number of segregating sites, the number of haplotypes, haplotype diversity (Hd), and nucleotide diversity (π) for each clade.

Results

We sequenced 1,143 base pairs of the mitochondrial cyt-b in specimens of Peromyscus megalops (1), P. carolpattonae (2), P. gardneri (1), Peromyscus “L” (sensu Pérez-Consuegra & Vázquez-Domínguez, 2017; 1), Peromyscus “O” (sensu Pérez-Consuegra & Vázquez-Domínguez, 2017; 1), P. m. mexicanus (2), P. m. teapensis (2), P. m. tehuantepecus (2), P. m. totontepecus (2), P. nudipes (2), P. salvadorensis (1), and P. tropicalis (1) (see Appendix for museum catalog numbers and GenBank Accessions). With these and previously published sequences, we analyzed 59 individuals in total. Our alignment was complete at > 92% of positions, contained 354 variable characters and 302 parsimony-informative characters.

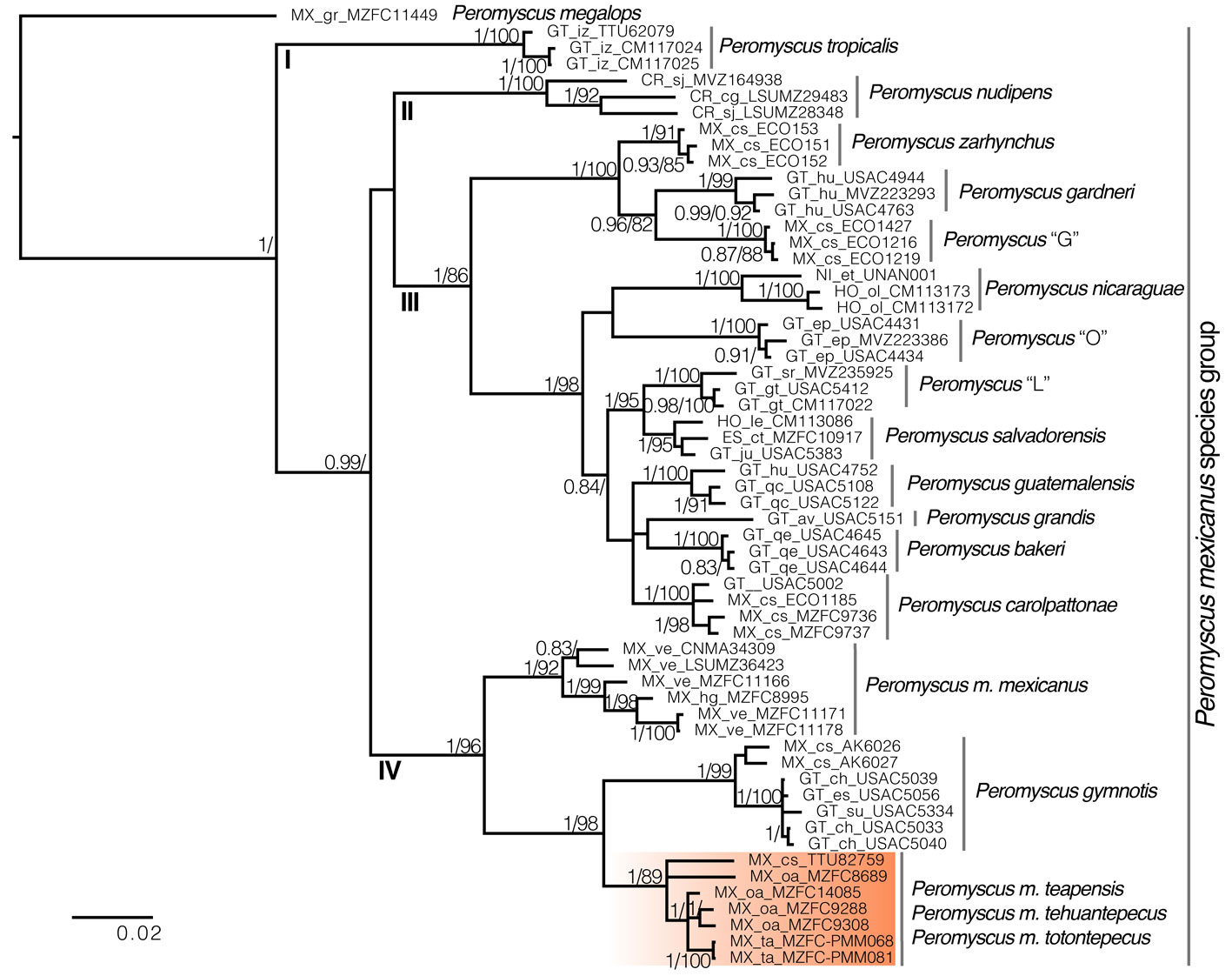

The best evolutionary model scheme used was K80+I+G, HKY+I, and HKY+G applied to the first, second, and third codon positions, respectively. Topologies from ML and BI had only slight differences. The ML tree showed an unsupported but resolved clade where P. guatemalensis was sister to P. grandis + P. bakeri, and all of them were sister to P. carolpattonae; however, in the BI topology P. guatemalensis, P. grandis + P. bakeri, and P. carolpattonae formed a polytomy. Similarly, the ML tree showed an unsupported clade where the sample MZFC 14085 (P. m. totontepecus) was sister to P. m. teapensis, and these specimens were sister to P. m. tehuantepecus; however, in the BI the sample MZFC 14085, P. m. teapensis, and P. m. tehuantepecus appeared as another polytomy.

There are 4 main clades within this group: I) P. tropicalis (Guatemala), II) P. nudipes (Costa Rica), III) 11 subclades that mainly inhabit highlands from Chiapas, Mexico to Nicaragua, and IV) 3 subclades that mainly inhabit low and mid altitudes from Mexico to Guatemala (Fig. 2). Even though bootstrap values and posterior probabilities supported the monophyly of these 4 clades, their relationships were highly supported in the BI tree, but unsupported in the ML analysis. However, the sister relationship between clades II and III did not receive significant support values in either ML or BI (Fig. 2). Within clade III, we found that P. zarhynchus was sister to P. gardneri + Peromyscus “G”; P. salvadorensis was sister to Peromyscus “L”; and P. salvadorensis + Peromyscus “L” was sister to an unresolved subclade that includes P. carolpattonae, P. guatemalensis, and P. grandis + P. bakeri. Besides, P. bakeri, P. carolpattonae, P. grandis, P. guatemalensis, Peromyscus “L”, and P. salvadorensis were sister to P. nicaraguae and Peromyscus “O”. Within clade IV, P. mexicanus was paraphyletic. Peromyscus m. mexicanus (Hidalgo and Veracruz) was sister to a well-supported subclade that placed samples of P. m. teapensis from Chiapas and Tabasco (TTU 82759, MZFC-PMM068, MZFC-PMM081), P. m. tehuantepecus from southeastern Oaxaca (MZFC 9288, MZFC 9308), and P. m. totontepecus from northeastern Oaxaca (MZFC 8689, MZFC 14085) as sister to P. gymnotis (Pacific slope in Mexico and Guatemala). The constrained analyses, which forced P. m. teapensis, P. m. tehuantepecus, or P. m. totontepecus to be members of P. mexicanus, generated worse likelihoods in all cases, and the Shimodaira-Hasegawa test rejected each constraint with p-values < 0.001

(Table 1).

Table 1

Results of Shimodaira-Hasegawa tests of alternative phylogenetic hypotheses (unconstrained = obtained in this work from BI, constrained = monophyly of P. m. teapensis, P. tehuantepecus, or P. m. totontepecus forced with all other P. m. mexicanus samples), with and without optimizing the rate matrices, gamma distribution, invariable sites, and base frequencies.

| No optimization | Optimization | |||||

| In L | ∂ L | p | In L | ∂ L | p | |

| Unconstrained | -7562.456 | 0.000 | 0.6322 | -6542.206 | 0.000 | 0.6049 |

| Constrained (P. m. teapensis) | -7648.348 | 85.892 | 0.0001 | -6590.713 | 48.506 | 0.0000 |

| Constrained (P. m. tehuantepecus) | -7646.114 | 83.658 | 0.0001 | -6586.746 | 44.539 | 0.0001 |

| Constrained (P. m. totontepecus) | -7650.158 | 87.703 | 0.0001 | -6589.963 | 47.756 | 0.0013 |

In the AMOVAs, the percentage of variation within localities was minimal in both comparisons, so samples of P. m. mexicanus, P. gymnotis, P. m. teapensis, P. m. tehuantepecus, and P. m. totontepecus did not show signs of mitochondrial panmixia. When P. gymnotis, P. m. teapensis, P. m. tehuantepecus, and P. m. totontepecus were treated as 1 group, the most variation (53.02%) was attributed to among-locality diversity. However, when P. gymnotis was considered an independent group from P. m. teapensis + P. m. tehuantepecus + P. m. totontepecus, the most significant variation was detected among clades (63.25%), reflecting substantial differentiation between them. These results support that P. m. mexicanus, P. gymnotis, and P. m. teapensis + P. m. tehuantepecus + P. m. totontepecus are 3 significantly different mitochondrial groups (Table 2). In the following analyses, we considered samples of P. m. teapensis + P. m. tehuantepecus + P. m. totontepecus an independent group.

Peromyscus zarhynchus, P. tropicalis, Peromyscus “G”, P. nudipes, and P. nicaraguae showed the largest interspecific genetic distances (10.82 – 11.47%) (Fig. 3). In contrast, the smallest interspecific distances were detected among the highland taxa of clade III, which ranged between 2.9 and 4.5%. In clade IV, the genetic distance between P. m. mexicanus and P. gymnotis was 8.31 (range = 7.51 – 9.41), and between P. m. mexicanus and P. m. teapensis + P. m. tehuantepecus + P. m. totontepecus it was 7.53 (range = 6.5 – 8.72), whereas between P. gymnotis and P. m. teapensis + P. m. tehuantepecus + P. m. totontepecus the distance was 6.13 (range = 5.15 – 7.35) (Fig. 3). Finally, in P. mexicanus, P. gymnotis, and P. m. teapensis + P. m. tehuantepecus + P. m. totontepecus, we found high haplotype diversity (Hd > 0.95), but within each species all haplotypes were similar (π < 0.024, segregating sites ≤ 56) (Table 3).

Table 2

AMOVA comparisons between P. mexicanus populations and P. gymnotis. k = Number of groups tested, Pv = percentage of variation, F = F index, and p = p values. mex = P. m. mexicanus, gym = P. gymnotis, tea = P. m. teapensis, teh = P. m. tehuantepecus, and tot = P. m. totontepecus.

| Source of variation | k | Grouping | Pv | F | p | k | Grouping | Pv | F | p |

| Among clades | (mex) vs | 42.88 | 0.429 | 0.0003 | (mex) vs | 63.25 | 0.633 | 0 | ||

| Among localities within clades | 2 | (gym + tea/teh/tot) | 53.02 | 0.928 | 0 | 3 | (gym) vs | 32.33 | 0.88 | 0.0001 |

| Within localities | 4.1 | 0.959 | 0 | (tea/teh/tot) | 4.42 | 0.956 | 0 |

Table 3

Genetic diversity summary statistics for P. mexicanus and closely related species. n = Sample size, S = number of segregating sites, h = number of haplotypes, Hd = haplotype diversity, π = nucleotide diversity, SD = standard deviation. Peromyscus tea/teh/tot = P. m. teapensis, P. m. tehuantepecus, and P. m. totontepecus.

| n | S | h | Hd | SD (Hd) | π | SD (π) | |

| Peromyscus mexicanus | 6 | 56 | 6 | 1 | 0.096 | 0.023 | 0.004 |

| Peromyscus gymnotis | 7 | 34 | 7 | 1 | 0.076 | 0.011 | 0.003 |

| Peromyscus tea/teh/tot | 7 | 56 | 6 | 0.952 | 0.096 | 0.018 | 0.004 |

Discussion

Relationships between members of the P. mexicanus species group have been confused because of relatively conserved morphology and karyotypes (Rogers & Engstrom, 1992). However, more recent molecular analyses of cyt-b identified 15 clades that subsequently were re-defined as discrete and allopatric populations fragmented by topography (Pérez-Consuegra & Vázquez-Domínguez, 2015, 2017). Here, we analyzed samples from P. m. teapensis, P. m. tehuantepecus, and P. m. totontepecus, subspecies that have not had their systematic placement tested with molecular data. We detected a previously unknown clade and showed that P. mexicanus is a paraphyletic assemblage. Peromyscus m. teapensis + P. m. tehuantepecus + P. m. totontepecus were sister to P. gymnotis, not to any other P. mexicanus (Fig. 2, Table 1). These 3 clades are highly divergent (Table 2, and genetic distances from 5.15 to 9.41) compared with many other interspecific mitochondrial distances within the P. mexicanus species group (Fig. 3) (Álvarez-Castañeda et al., 2019; Pérez-Consuegra & Vázquez-Domínguez, 2015). In the P. mexicanus group, smaller interspecific genetic distances (from 3.59 %) are supported by overall size differences, qualitative cranial traits, univariate and multivariate analyses of craniodental morphometric variables, and allopatric distributions (Álvarez-Castañeda et al., 2019; Lorenzo et al., 2016; Pérez-Consuegra & Vázquez-Domínguez, 2017). There are 2 possibilities to solve the paraphyly noticed in P. mexicanus. The first one is to assign the populations of P. m. teapensis, P. m. tehuantepecus, and P. m. totontepecus to P. gymnotis. The second one is to recognize the clade P. m. teapensis + P. m. tehuantepecus + P. m. totontepecus as a different species, and we agree with this hypothesis considering their monophyly and high levels of mitochondrial differentiation. Between P. m. teapensis, P. m. tehuantepecus, and P. m. totontepecus (and even including P. m. azulensis, a subspecies not analyzed here, but that is geographically located between P. m. teapensis, P. m. tehuantepecus, and P. m. totontepecus; Fig. 1), P. totontepecus is the oldest available name, so we recommend referring to this clade as P. totontepecus Merriam, 1898 and treating P. m. teapensis and P. m. tehuantepecus as a junior synonyms. The status of P. m. azulensis remains unresolved.

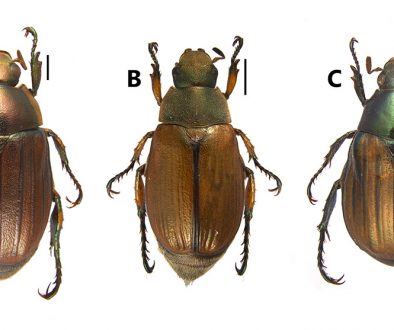

Although future research should test our taxonomic hypothesis with phenotypic and more genetic data, previous studies support our findings. Allozyme variation indicated that samples from northwestern Chiapas (P. totontepecus) shared 2 derived allelic character states with P. gymnotis (Rogers & Engstrom, 1992). Mitochondrial sequences of cyt-b, ND3, ND4L, and ND4 also showed a couple of samples from northern Chiapas sister to P. gymnotis, and all of them were sisters to P. mexicanus from Veracruz (Wade, 1999). In the most recent molecular revision of this species group, based on cyt-b, 3 specimens from northern Chiapas and southern Veracruz were treated as P. cf. gymnotis because those individuals were more closely related to P. gymnotis than to P. mexicanus (Pérez-Consuegra & Vázquez-Domínguez, 2017). Moreover, P. m. totontepecus was initially described as a larger and darker subspecies than P. mexicanus (Merriam, 1898). These pieces of evidence reported previously, including allozymes, DNA sequences from 4 mitochondrial genes, and morphological differences, support recognition of P. totontepecus as an independent lineage.

Additionally, there are intraspecific morphological differences in P. totontepecus. For example, P. m. teapensis was considered similar to P. totontepecus but with some modest differences in color and the skull (Osgood, 1904). These morphological differences were also reported in a more recent analysis of cranial variation, but it was suggested that P. teapensis and P. totontepecus should be treated as independent species (Zaragoza-Quintana, 2005). Based on cranial and external measurements, cranial characters, and fur color traits that we used to verify the specimens analyzed here (Merriam, 1898; Osgood, 1904), we agree with previous reports, which show some intraspecific variation in P. totontepecus. Furthermore, based on their size, color, and geographic range (Merriam, 1898), we clearly differentiated the specimens MZFC 9288 and MZFC 9308 as “P. m. tehuantepecus”, a subspecies not recognized by Ramírez-Pulido et al. (2005), Trujano-Álvarez & Álvarez-Castañeda (2010), and Pardiñas et al. (2017), but that was recently re-considered as a subspecies of P. mexicanus (Ramírez-Pulido et al., 2014). Future studies should analyze interspecific morphological differences between P. mexicanus, P. totontepecus, and P. gymnotis, but also the intraspecific morphological variation detected in P. totontepecus deserves attention (Osgood, 1904; Zaragoza-Quintana, 2005).

Based on our results, the geographic distribution of P. gymnotis covers the foothills and adjacent coastal plains in southern Chiapas and northern Guatemala, P. mexicanus ranges from San Luis Potosí to central Veracruz (in the Sierra Madre Oriental), and P. totontepecus likely has a continuous distribution from northeastern Oaxaca to northern Chiapas, including southern Veracruz and southern Tabasco (Fig. 4). It was previously reported that the Isthmus of Tehuantepec (lowlands between Chiapas and Oaxaca) has been a significant barrier that deer mice in the P. mexicanus species group have rarely crossed (Ordóñez-Garza et al., 2010). Our findings agree with this hypothesis because only 2 clades are found to the west (P. mexicanus, and P. totontepecus), but 14 clades are restricted to the mountains east of the isthmus (all species in clades I, II, III, in addition to P. gymnotis). These lowlands are well documented as a geographical barrier for other highland mammals such as shrews (Woodman & Timm, 1999), harvest mice (Arellano et al., 2005), crested tailed mice (León-Paniagua et al., 2007), and other deer mice (Sullivan et al., 1997). However, we found an exception when we analyzed samples of P. totontepecus from both sides of the isthmus. Contrary to previous expectations, mitochondrial sequences were quite similar (Fig. 2, Table 2), showing that the Isthmus of Tehuantepec has acted as a geographic barrier in the P. mexicanus species group, but not for all species (see references in Cortés-Rodríguez et al., 2013). The species that live in the highest elevations in the P. mexicanus group are placed in the clades II and III, and all of them are restricted to the east (Pérez-Consuegra & Vázquez-Domínguez, 2015, 2017). However, P. mexicanus and P. gymnotis (clade IV) inhabit low and mid-elevations (Pérez-Consuegra & Vázquez-Domínguez, 2017), as is P. totontepecus (collected between 30 to 2,047 m). At least during interglacial periods like the present, it would be logical for the Isthmus of Tehuantepec to represent a lesser barrier to species adapted to low and middle elevations than those adapted to high elevation ecosystems. This ecological difference between species could explain the dual effect of this isthmus on the evolutionary history of these deer mice.

Our taxonomic hypotheses relied on a single-locus dataset. Still, findings of high levels of genetic divergence, backed by previous allozymic and morphological data, in addition to other mitochondrial loci, provide a better picture of the systematics of the P. mexicanus group. Essential aspects of Peromyscus biology, such as their taxonomic and phylogenetic relationships, are still not clear (Bradley et al., 2007; Miller & Engstrom, 2008; Platt et al., 2015; Sullivan et al., 2017), for example, P. m. angelensis, P. m. azulensis, and P. m. putlaensis have not been included in any molecular phylogenies, and their systematic relationships should be analyzed (Fig. 4). Further research will be crucial to understand the number of Peromyscus species and their phylogenetic relationships. Given their commonness and importance as model organisms (Bradley et al., 2007), this should be a high priority.

Acknowledgments

To Christopher Conroy, Michael Nachman, Eileen Lacey, and James Patton at the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology and Caleb Phillips; Robert Bradley, and Terri Carnes at the Texas Tech Museum for facilitating access to tissue samples; Heru Handika, Mark Swanson, Jonathan Nations, Diego Elias, and Donna Dittmann for assistance with labwork; two anonymous reviewers for comments and criticisms; and the Posgrado en Ciencias Biológicas – UNAM and Pablo Colunga-Salas for its support to conduct this research. Funding was provided by the U. S. National Science Foundation (NSF DEB-1754393), the Mexican National Council for Science and Technology (CONACyT CVU-549963), and Programa de Becas Posdoctorales DGAPA – UNAM.

Appendix. Specimens examined in this study. Species names are followed by country, state, locality, geographic coordinates, catalog number and Genbank accession number. Sequences generated in this work are shown with an asterisk.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Peromyscus megalops.– Mexico: Guerrero, “Puerto del Gallo”, 17.474, -100.179 (MZFC 11449 – MZ510912*).

Peromyscus bakeri.– Guatemala: Quetzaltenango, “Fuentes Georginas, 3.8 km S, 0.3 km E Zunil”, 14.750, -91.480 (USAC 4643 – KP284382; USAC 4644 – KP284383; USAC 4645 – KP284384).

Peromyscus carolpattonae.– Guatemala: “Parque Regional Municipal de San Marcos, ca. 0.8 km N, 4.2 km W San Marcos”, 14.974, -91.827 (USAC 5002 – KP284370); Mexico: Chiapas, “Campamento El Triunfo, RB El Triunfo, Poligono I, Mpio. Angel Albino Corzo”, 15.645, -92.810 (ECO 1185 – KP284365), “Chiquihuites, 1.3 km NNW”, 15.106, -92.103, (MZFC 9736 – MZ510920*; MZFC 9737 – MZ510921*).

Peromyscus gardneri.– Guatemala: Huehuetenango, “2.8 km S Aldea Yalambojoch, San Mateo Ixtatán”, 15.963, -91.571 (USAC 4763 – KP284340), “Aldea San José Maxbal, 15.4 km N Santa Cruz Barillas”, 15.946, -91.307 (USAC 4944 – KP284339), “Finca Ixcansán, 10.3 km (by road) E of Yalambojoch on road to Rio Seco, Sierra de los Cuchumatanes”, 16.006, -91.500 (MVZ 223293 – MZ510916*).

Peromyscus grandis.– Guatemala: Alta Verapaz, “Finca Bethel, San Pedro Carcha”, 15.612, -90.273 (USAC 5151 – KP284306).

Peromyscus guatemalensis.– Guatemala: Huehuetenango, “Cerro Bobi, 2.5 km S, 2.75 km W San Mateo Ixtatan”, 15.805, -91.506 (USAC 4752 – KP284363); Quiche, “LajChimel, 12.6 km N, 9.0 km E Uspatan”, 15.462, -90.788 (USAC 5108 – KP284351; USAC 5122 – KP284354).

Peromyscus gymnotis.– Guatemala: Chimaltenango, “Comunidad Unión Victoria, 2.7 km N, 3.8 km E Pochuta”, 14.575, -91.049 (USAC 5033 – KP284385; USAC 5039 – KP284386; USAC 5040 – KP284387); Escuintla, “Finca Jurun [Montaña El Chilar], Palin”, 14.356, -90.727 (USAC 5056 – KP284388); Suchitepequez, “Finca Los Andes, Patulul”, 14.549, -91.181 (USAC 5334 – KP284389); Mexico: Chiapas, “21 km SE Mapastepec”, 15.337, -92.727 (AK6026 – EF028169; AK6027 – EF028170).

Peromyscus G.– Mexico: Chiapas, “Las Grutas, 3.45 km N El Vivero, Lagos de Montebello National Park”, 16.135, -91.727 (ECO 1216 – KP284334; ECO 1219 – KP284335; ECO 1427 – KP284332).

Peromyscus L.– Guatemala: Guatemala, “El Frutal, 7.3 km S, 2.8 km W Museo Nac. Historia Natural, Ciudad de Guatemala”, 14.530, -90.558 (CM 117022 – KP284421), “Río Pachum, San Antonio Las Trojes, San Juan Sacatepequez”, 14.755, -90.702 (USAC 5412 – KP284412); Santa Rosa, “Volcan Tecuamburro, Pueblo Nuevo Viñas”, 14.152, -90.416 (MVZ 235925 – MZ510918*).

Peromyscus O.– Guatemala: El Progreso, “3 km W Pinalón, Reserva de Biosfera Sierra de las Minas”, 15.081, -89.943 (MVZ 223386 – MZ510917*), “La Cabaña, 3 km W Cerro Pinalón, Las Minas Biosphere Reserve”, 15.081, -89.943 (USAC 4431 – KP284374; USAC 4434 – KP284376).

Peromyscus mexicanus.– Mexico: Hidalgo, “Puente del Río Camarones, Tutotepec”, 20.391, -98.223 (MZFC 8995 – KP284424); Veracruz, “10 km SE (por carretera) Zongolica”, 18.621, -96.969 (CNMA 34309 – EF028174), “Manuel Gutiérrez Nájera, Misantla”, 19.792, -96.861 (MZFC 11178 – KP284422), “Ojo de Agua, 8 km NW Potrero”, 18.926, -96.883 (LSUMZ 36423 – MZ510922*), “Pueblo Viejo, Misantla”, 19.814, -96.868 (MZFC 11171 – KP284423), “San Felipe Cerro Quebrado I”, 20.004, -96.917 (MZFC 11166 – MZ510923*).

Peromyscus nicaraguae.– Honduras: Olancho, “La Picucha trail, Babilonia Mountain, Agalta National Park”, 14.957, -85.918 (CM 113172 – KP284322; CM 113173 – KP284326); NICARAGUA: Estelí, “Posada Tisey, Area Protegida Tisey-Estanzuela”, 12.985, -86.370 (UNAN 001 – KP284313).

Peromyscus nudipes.– Costa Rica: Cartago, “2 km W Santa Rosa”, 9.917, -83.868 (LSUMZ 29483 – MZ510914*); San José, “División”, 9.506, -83.708 (LSUMZ 28348 – MZ510915*), “2.2 km E (by road) La Trinidad de Dota”, 9.672, -83.855 (MVZ 164938 – KP284425).

Peromyscus salvadorensis.– El Salvador: Chalatenango, “Cerro El Pital”, 13.942, -88.950 (MZFC 10917 – MZ510919*); Guatemala: Jutiapa, “Volcan Suchitan, 4.8 km S, 4 km W Sta. Catarina Mita”, 14.404, -89.781 (USAC 5383 – KP284407); Honduras: Lempira, “Naranjo camping station, Celaque National Park”, 14.533, -88.667 (CM 113086 – KP284391).

Peromyscus totontepecus.– Mexico: Chiapas, “14.4 km N Ocozocoaulta”, 16.861, -93.453 (TTU 82759 – AY376425); Oaxaca, “Nizanda – Los Mangos, cañada”, 16.686, -95.034 (MZFC 9288 – MZ510924*), “Nizanda, Cerro Verde”, 16.666, -95.006 (MZFC 9308 – MZ510925*), “Puerto Eligio”, 17.260, -96.527 (MZFC 14085 – MZ510927*), “San Martín Caballero”, 18.113, -96.637 (MZFC 8689 – MZ510926*); Tabasco, “Grutas de Coconá”, 17.564, -92.929 (MZFC-PMM068 – MZ510928*; MZFC-PMM081 – MZ510929*).

Peromyscus tropicalis.– Guatemala: Izabal, “Cerro San Gil”, 15.667, -88.783 (TTU 62079 – MZ510913*), “Las Escobas, ca.1.3 km NE Las Torres, Cerro San Gil Reserve”, 15.685, -88.645 (CM 117024 – KP284307; CM 117025 – KP284308).

Peromyscus zarhynchus.– Mexico: Chiapas, “3 km NW Tapalapa, Mpio. Tapalapa”, 17.193, -93.123 (ECO 151 – KP284328; ECO 152 – KP284329; ECO 153 – KP284330).

________________________________________________________________________________________________

References

Álvarez-Castañeda, S. T., Álvarez, T., & González-Ruiz, N. (2015). Guía para la identificación de los mamíferos de México en campo y laboratorio. Guadalajara: Centro de Investigaciones del Noroeste, S. C./ Asociación Mexicana de Mastozoología, A. C.

Álvarez-Castañeda, S. T., Lorenzo, C., Segura-Trujillo, C. A., & Pérez-Consuegra, S. G. (2019). Two new species of Peromyscus from Chiapas, Mexico, and Guatemala. In R. D. Bradley, H. H. Genoways, D. J. Schmidly, & L. C. Bradley (Eds.), From field to laboratory: a memorial volume in honor to Robert J. Baker (pp. 543–558). Special Publications 71. Lubbock, TX: Museum of Texas Tech University.

Arellano, E., González-Cozátl, F. X., & Rogers, D. S. (2005). Molecular systematics of Middle American harvest mice Reithrodontomys (Muridae), estimated from mitochondrial cytochrome b gene sequences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 37, 529–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2005.07.021

Ávila-Valle, Z. A., Castro-Campillo, A., León-Paniagua, L., Salgado-Ugalde, I. H., Navarro-Sigüenza, A. G., Hernández-Baños, B. E. et al. (2012). Geographic variation and molecular evidence of the blackish deer mouse complex (Peromyscus furvus, Rodentia: Muridae). Mammalian Biology, 77, 166–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mambio.2011.09.008

Bradley, R. D., Durish, N. D., Rogers, D. S., Miller, J. R., Engstrom, M. D., & Kilpatrick, C. W. (2007). Toward a molecular phylogeny for Peromyscus: evidence from mitochondrial cytochrome- b sequences. Journal of Mammalogy, 88, 1146–1159. https://doi.org/10.1644/06-mamm-a-342r.1

Bradley, R. D., Edwards, C. W., Carroll, D. S., & Kilpatrick, C. W. (2004). Phylogentic relationships of neotomine-peromyscine rodents: based on DNA sequencues from the mitochondrial cytochrome-b gene. Journal of Mammalogy, 85, 389–395. https://doi.org/10.1644/ber-026

Bradley, R. D., Francis, J. Q., Platt, R. N., Soniat, T. J., Alvarez, D., & Lindsey, L. L. (2019). Mitochondrial DNA sequence data indicate evidence for multiple species within Peromyscus maniculatus (Issue 70). Lubbock, TX: Museum of Texas Tech University. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsnr.1961.0025

Bradley, R. D., Ordóñez-Garza, N., Ceballos, G., Rogers, D. S., & Schmidly, D. J. (2017). A new species in the Peromyscus boylii species group (Cricetidae: Neotominae) from Michoacán, México. Journal of Mammalogy, 98, 154–165. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmammal/gyw160

Carleton, M. D. (1980). Phylogenetic relationships in neotomine-peromyscine rodents (Muroidea) and a reappraisal of the dichotomy within New World Cricetinae. Miscellaneous Publications Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan, 157, 1–146.

Carleton, M. D. (1989). Systematics and evolution. In G. L. J. Kirkland, & J. N. Layne (Eds.), Advances in the study of Peromyscus (Rodentia) (pp. 7–141). Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech University Press.

Castañeda-Rico, S., León-Paniagua, L., Vázquez-Domínguez, E., & Navarro-Sigüenza, A. G. (2014). Evolutionary diversification and speciation in rodents of the Mexican lowlands: the Peromyscus melanophrys species group. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 70, 454–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2013.10.004

Cortés-Rodríguez, N., Jacobsen, F., Hernández-Baños, B. E., Navarro-Sigüenza, A. G., Peters, J. L., & Omland, K. E. (2013). Coalescent analyses show isolation without migration in two closely related tropical orioles: the case of Icterus graduacauda and Icterus chrysater. Ecology and Evolution, 3, 4377–4387. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.768

Durish, N. D., Halcomb, K. E., Kilpatrick, C. W., & Bradley, R. D. (2004). Molecular systematics of the Peromyscus truei species group. Journal of Mammalogy, 85, 1160–1169. https://doi.org/10.1644/ber-115.1

Excoffier, L., & Lischer, H. E. L. (2010). Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Molecular Ecology Resources, 10, 564–567. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02847.x

Goodwin, G. G. (1956). Seven new mammals from México. American Museum Novitates, 1791, 1–10.

Goodwin, G. G. (1964). A new species and a new subspecies of Peromyscus from Oaxaca, Mexico. American Museum Novitates, 2183, 1–8.

Greenbaum, I. F., Honeycutt, R. L., & Chirhart, S. E. (2019). Taxonomy and phylogenetics of the Peromyscus maniculatus species group. In R. D. Bradley, H. H. Genoways, D. J. Schmidly, & L. C. Bradley (Eds.), From field to laboratory: a memorial volume in honor to Robert J. Baker (pp. 559–575). Special Publications 71. Lubbock, TX: Museum of Texas Tech University.

Guevara, L., & Cervantes, F. A. (2014). Molecular systematics of small-eared shrews (Soricomorpha, Mammalia) within Cryptotis mexicanus species group from Mesoamérica. Acta Theriologica, 59, 233–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13364-013-0165-6

Guevara, L., Sánchez-Cordero, V., León-Paniagua, L., & Woodman, N. (2014). A new species of small-eared shrew (Mammalia, Eulipotyphla, Cryptotis) from the Lacandona rain forest, Mexico. Journal of Mammalogy, 95, 739–753. https://doi.org/10.1644/14-mamm-a-018

Hernández-Canchola, G., & León-Paniagua, L. (2021). About the specific status of Baiomys musculus and B. brunneus. Therya, 12, 291–301. https://doi.org/10.12933/therya-21-1150

Hernández-Canchola, G., León-Paniagua, L., & Esselstyn, J. A. (2021). Mitochondrial DNA indicates paraphyletic relationships of disjunct populations in the Neotoma mexicana species group. Therya, 12, 411–421. https://doi.org/10.12933/therya-21-1082

Hsu, T. C., & Arrighi, F. E. (1966). Chromosomal evolution in the genus Peromyscus (Cricetidae, Rodentia). Cytogenetics, 5, 355–359.

Irwin, D. M., Kocher, T. D., & Wilson, A. C. (1991). Evolution of the cytochrome b gene of mammals. Journal of Molecular Evolution, 32, 128–144.

Kimura, M. (1980). A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. Journal of Molecular Evolution, 16, 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01731581

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C., & Tamura, K. (2018). MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35, 1547–1549. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy096

Lanfear, R., Frandsen, P. B., Wright, A. M., Senfeld, T., & Calcott, B. (2016). PartitionFinder 2: new methods for selecting partitioned models of evolution for molecular and morphological phylogenetic analyses. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 34, 772–773.

León-Paniagua, L., Navarro-Sigüenza, A. G., Hernández-Baños, B. E., & Morales, J. C. (2007). Diversification of the arboreal mice of the genus Habromys (Rodentia: Cricetidae: Neotominae) in the Mesoamerican highlands. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 42, 653–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2006.08.019

León-Tapia, M. Á. (2013). Ubicación filogenética con caracteres moleculares de la rata de monte (Nelsonia goldmani), endémica del Eje Neovolcánica Transversal (Master Thesis). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico.

León-Tapia, M. Á., Fernández, J. A., Rico, Y., Cervantes, F. A., & Espinosa-de los Monteros, A. (2020). A new mouse of the Peromyscus maniculatus species complex (Cricetidae) from the highlands of central Mexico. Journal of Mammalogy, 101, 1117–1132. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmammal/gyaa027

Librado, P., & Rozas, J. (2009). DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics, 25, 1451–1452. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187

López-González, C., García-Mendoza, D. F., López-Vidal, J. C., & Elizalde-Arellano, C. (2019). Multiple lines of evidence reveal a composite of species in the plateau mouse, Peromyscus melanophrys (Rodentia, Cricetidae). Journal of Mammalogy, 100, 1583–1598. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmammal/gyz106

Lorenzo, C., Álvarez-Castañeda, S. T., Pérez-Consuegra, S. G., & Patton, J. L. (2016). Revision of the Chiapan deer mouse, Peromyscus zarhynchus, with the description of a new species. Journal of Mammalogy, 97, 910–918. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmammal/gyw018

Merriam, C. H. (1898). Descriptions of twenty new species and a new subgenus of Peromyscus from Mexico and Guatemala. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington, 12, 115–125.

Miller, J. R., & Engstrom, M. D. (2008). The relationships of major lineages within peromyscine rodents: a molecular phylogenetic hypothesis and systematic reappraisal. Journal of Mammalogy, 89, 1279–1295. https://doi.org/10.1644/07-mamm-a-195.1

Nguyen, L. T., Schmidt, H. A., von Haeseler, A., & Minh, B. Q. (2015). IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 32, 268–274. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msu300

Ordóñez-Garza, N., Matson, J. O., Strauss, R. E., Bradley, R. D., & Salazar-Bravo, J. (2010). Patterns of phenotypic and genetic variation in three species of endemic Mesoamerican Peromyscus (Rodentia: Cricetidae). Journal of Mammalogy, 91, 848–859. https://doi.org/10.1644/09-mamm-a-167.1

Osgood, W. H. (1904). Thirty new mice of the genus Peromyscus from Mexico and Guatemala. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington, 17, 55–77.

Osgood, W. H. (1909). Revision of the mice of the American genus Peromyscus. North American Fauna, 28, 1–285.

Pardiñas, U., Myers, P., León-Paniagua, L., Ordóñez-Garza, N., Cook, J., Kryštufek, B. et al. (2017). Family Cricetidae (true hamsters, voles, lemmings and new world rats and mice). In D. E. Wilson, R. A. Mittermeier, & T. E. Lacher (Eds.), Handbook of the mammals of the World. Volume 7 Rodents II (pp. 204–279). Barcelona: Lynx Edicions.

Patterson, J., Chamberlain, B., & Thayer, D. (2004). Finch TV Version 1.4.0. Published by authors.

Pérez-Consuegra, S. G., & Vázquez-Domínguez, E. (2015). Mitochondrial diversification of the Peromyscus mexicanus species group in Nuclear Central America: biogeographic and taxonomic implications. Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research, 53, 300–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/jzs.12099

Pérez-Consuegra, S. G., & Vázquez-Domínguez, E. (2017). Intricate evolutionary histories in montane species: a phylogenetic window into craniodental discrimination in the Peromyscus mexicanus species group (Mammalia: Rodentia: Cricetidae). Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research, 55, 57–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/jzs.12155

Platt, R. N., Amman, B. R., Keith, M. S., Thompson, C. W., & Bradley, R. D. (2015). What is Peromyscus? Evidence from nuclear and mitochondrial DNA sequences suggests the need for a new classification. Journal of Mammalogy, 96, 708–719. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmammal/gyv067

Rambaut, A., Drummond, A. J., Xie, D., Baele, G., & Suchard, M. A. (2018). Posterior summarization in bayesian phylogenetics using Tracer 1.7. Systematic Biology, 67, 901–904. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syy032

Ramírez-Pulido, J., Arroyo-Cabrales, J., & Castro-Campillo, A. (2005). Estado actual y relación nomenclatural de los mamíferos terrestres de México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana, 21, 21–82. https://doi.org/10.21829/azm.2005.2112008

Ramírez-Pulido, J., González-Ruiz, N., Gardner, A. L., & Arroyo-Cabrales, J. (2014). List of recent land mammals of Mexico, 2014. Special Publications 63. Lubbock, TX: The Museum Tech University.

Rogers, D. S., & Engstrom, M. D. (1992). Evolutionary implications of allozymic variation in tropical Peromyscus of the mexicanus species group. Journal of Mammalogy, 73, 55–69.

Rogers, D. S., Funk, C. C., Miller, J. R., & Engstrom, M. D. (2007). Molecular phylogenetic relationships among crested-tailed mice (genus Habromys). Journal of Mammalian Evolution, 14, 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10914-006-9034-2

Ronquist, F., Teslenko, M., Van Der Mark, P., Ayres, D. L., Darling, A., Höhna, S. et al. (2012). Mrbayes 3.2: efficient bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Systematic Biology, 61, 539–542. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/sys029

Schliep, K. P. (2011). phangorn: phylogenetic analysis in R. Bioinformatics, 27, 592–593. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btq706

Shimodaira, H., & Hasegawa, M. (1999). Multiple comparisons of log-likelihoods with applications to phylogenetic inference. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 16, 1114–1116. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00675.x

Smith, M. F., & Patton, J. L. (1993). The diversification of South American murid rodents: evidence from mitochondrial DNA sequence data for the akodontine tribe. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 50, 149–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.1993.tb00924.x

Stangl, F. B., & Baker, R. J. (1984). Evolutionary relationships in Peromyscus: congruence in chromosomal, genic, and classical data sets. Journal of Mammalogy, 65, 643–654.

Sullivan, J., Markert, J. A., & Kilpatrick, C. W. (1997). Phylogeography and molecular systematics of the Peromyscus aztecus species group (Rodentia: Muridae) inferred using parsimony and likelihood. Systematic Biology, 46, 426–440. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/46.3.426

Sullivan, K. A. M., Platt, R. N., Bradley, R. D., & Ray, D. A. (2017). Whole mitochondrial genomes provide increased resolution and indicate paraphyly in deer mice. BMC Zoology, 2, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40850-017-0020-3

Trujano-Álvarez, A. L., & Álvarez-Castañeda, S. T. (2010). Peromyscus mexicanus (Rodentia: Cricetidae). Mammalian Species, 42, 111–118. https://doi.org/10.1644/858.1

Vallejo, R. M., & González-Cózatl, F. X. (2012). Phylogenetic affinities and species limits within the genus Megadon-

tomys (Rodentia: Cricetidae) based on mitochondrial sequence data. Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research, 50, 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0469.2011.00634.x

Wade, N. L. (1999). Molecular systematics of Neotropical deer mice of the Peromyscus mexicanus species group (Master Thesis). University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada.

Wickham, H. (2011). ggplot2. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics, 3, 180–185. https://doi.org/10.1002/wics.147

Woodman, N., & Timm, R. M. (1999). Geographic variation and evolutionary relationships among broad-clawed shrews of the Cryptotis goldmani-group (Mammalia: Insectivora: Soricidae). Fieldiana: Zoology (New Series), 91, 1–35. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.2669

Zaragoza-Quintana, E. P. (2005). Variación geográfica de Peromyscus mexicanus (Rodentia: Muridae) en México (Bachelor Thesis). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico.