Alexander Czaja a, Jorge Luis Becerra-López a, José Luis Estrada-Rodríguez a, *, Ulises Romero-Méndez a, Gabriel Fernando Cardoza-Martínez a, Jorge Sáenz-Mata a, Josué Raymundo Estrada-Arellano a, Miguel Ángel Garza-Martínez a, Fernando Hernández-Terán b, Julián Cerano-Paredes c

a Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango, Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Av. Universidad s/n, Fraccionamiento Filadelfia, 35010 Gómez Palacio, Durango, Mexico

b Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Autónoma de Coahuila, Carretera Torreón Matamoros, Km. 7.5, Ejido el Águila, 27275 Torreón, Coahuila, Mexico

c Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales Agrícolas y Pecuarias, Departamento de Dendrocronología, Km. 6.5 margen derecha Canal de Sacramento, 35140 Gómez Palacio, Durango, Mexico

*Corresponding author: drjlestrada@ujed.mx (J.L. Estrada-Rodríguez)

Received: 17 June 2020; accepted: 11 June 2021

Abstract

The malacofauna of the Sabinas River basin, Coahuila, North Mexico, was studied at 9 sites. In total, 21 native and 2 invasive species were found. Nineteen species were gastropods and 4 species were bivalves. One genus and 2 species of subterranean gastropods are endemic to the area. We report for the first time, a member of the family Amnicolidae in Mexico, Lyogyrus sp. Mexithauma cf. quadripaludium Taylor, 1966 and Juturnia coahuilae (Taylor, 1966) (Cochliopidae), previously known only as endemic in the neighboring Cuatro Ciénegas basin, were found for the first time outside of this basin. Also, Cincinnatia integra (Say, 1821) (Hydrobiidae), previously known in Mexico only from 1 relict site in San Luis Potosí state, was found living in Sabinas River. In all studied sites, the invasive species Melanoides tuberculata (O. F. Müller, 1774) (Thiaridae) and Corbicula fluminea (O. F. Müller, 1774) (Cyrenidae) dominate the aquatic molluscan communities. Both molluscs are potential risks for native species, especially if the water pollution continues. At least 10 species from Sabinas River System are of special conservation significance (7 imperiled and 3 vulnerable), due to their endemism, extremely reduced habitat, or relict occurrence in Mexico.

Keywords: Diversity; Freshwater; Gastropods; Bivalves; Conservation

© 2022 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license

La cuenca del río Sabinas en Coahuila, un nuevo “hotspot” de biodiversidad de moluscos cerca de Cuatro Ciénegas, Desierto Chihuahuense, norte de México

Resumen

La malacofauna de 9 sitios a lo largo de la cuenca río Sabinas, Coahuila, México, fue investigada con base en características conquiliológicas. En total, se encontraron 23 especies de moluscos dulceacuícolas, de las cuales 21 son nativas y 2 invasoras. Diecinueve especies son gasterópodos y 4 son bivalvos. Un género y 2 especies de gasterópodos intersticiales son endémicos del área y se reporta por primera vez a un miembro de la familia Amnicolidae en México, Lyogyrus sp. Mexithauma cf. quadripaludium Taylor, 1966, y Juturnia coahuilae (Taylor, 1966) (Cochliopidae), localizados únicamente en el valle de Cuatro Ciénegas, fueron encontrados por primera vez fuera del mismo. Además, también Cincinnatia integra (Say, 1821) (Hydrobiidae), conocida en México hasta la fecha solamente como relicto de un solo sitio en San Luis Potosí, fue encontrada viva en el río Sabinas. Las especies invasoras Melanoides tuberculata (O. F. Müller, 1774) (Thiaridae) y Corbicula fluminea (O. F. Müller, 1774) (Cyrenidae) dominan a las comunidades acuáticas de moluscos en todos los sitios estudiados. Estos dos moluscos forman un riesgo potencial para las especies nativas, especialmente si la contaminación del agua causada por actividades antropogénicas continúa. Por lo menos 10 especies del sistema río Sabinas son de especial importancia para la conservación (7 amenazadas y 3 vulnerables) debido a su endemismo, al hábitat reducido o a su presencia como relicto en México.

Palabras clave: Diversidad; Dulceacuícola; Gasterópodos; Bivalvos; Conservación

© 2022 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. Este es un artículo Open Access bajo la licencia CC BY-NC-ND

Introduction

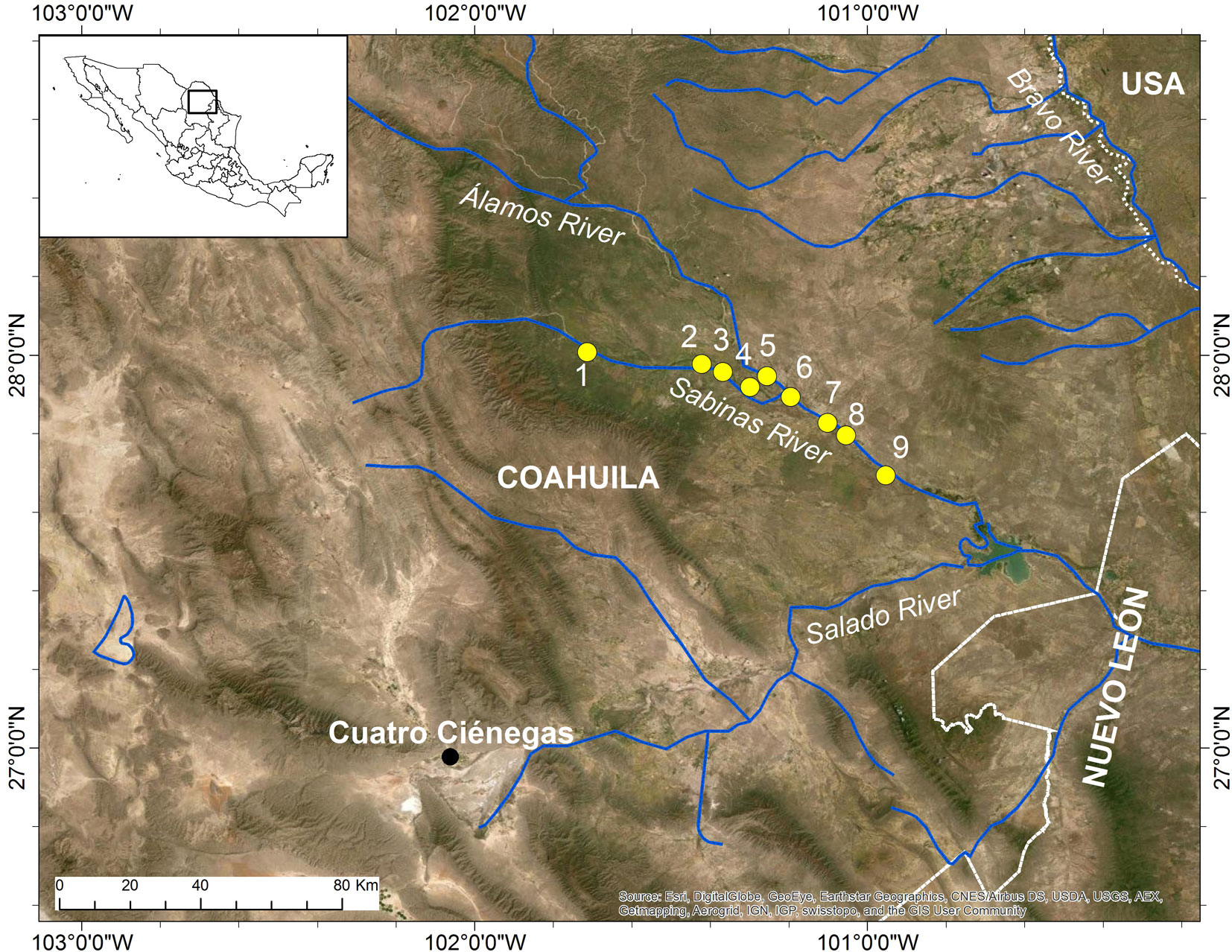

Freshwater molluscs are some of the most threatened species worldwide and their habitats are highly impacted by several human activities such as dam construction, water pollution, overexploitation of aquifers and habitat degradation (Dudgeon, 2020; Modesto et al., 2017). The decline of freshwater species diversity is a worldwide phenomenon but it is especially pronounced in arid regions such as in the Chihuahuan Desert of Coahuila and Durango, Northern Mexico (Czaja, Covich et al., 2019). The Sabinas River (Fig. 1) is probably one of the least investigated areas in the southeastern part of the Chihuahuan Desert and until now, only 3 species of gastropods have been reported from this region (Contreras-Arquieta, 1998; Czaja, Cardoza-Martínez et al., 2019).

Recently, the Sabinas River basin and the southern adjacent Cuatro Ciénegas Valley have been defined together as 1 (of 3) hotspots of molluscan biodiversity in Mexico (hotspot B sensu Czaja et al. [2020]). While the Cuatro Ciénegas basin is a complex of more than 700 springs, small lakes and marshes, the Sabinas basin is composed of 2 large rivers as typical habitat. The valley of Cuatro Ciénegas is one of the most extensively studied locations in North America in relation to molluscs and was identified as a separate freshwater ecoregion and as one of 25 worldwide hotspots of gastropod diversity by Strong et al. (2008). All 7 Mexican freshwater species listed as endangered by the Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Mexican Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources) (Semarnat, 2010) occur there.

The aim of the present study is to describe the diversity and conservation status of the molluscs collected at 9 sites (8 sites at Sabinas River and 1 site at Álamos River, Fig. 1) along the Sabinas River, Don Martín Basin, Coahuila. The area of study is part of the Natural Resources Protection Area, Upper Basin of the National Irrigation District 004 Don Martín, administered by the National Commission of Natural Protected Areas (Conanp). We provide important data that will serve as a basis for further development of conservation strategies of aquatic habitats of this area.

Materials and methods

The freshwater molluscs treated herein were collected in July and November 2018, and May 2019 in 9 sites along the Sabinas and Álamos Rivers (Figs. 1, 2A-F; Table 1). Two fine sand and gravel sediment samples of 2.5 kg each were taken from river shores, which were later screened through 2 sieves with mesh sizes of 0.2 mm and 0.5 mm. The sampling of molluscs was restricted to shallow water less than 1 m deep. The geographic coordinates were taken with a Garmin Etrex 10 GPS (accuracy: 4-10 m).

We agree with the conclusions of Vinarski (2018) regarding the problem of species delimitation in freshwater malacology and the need for an integrative approach. With the exception of Physella, Biomphalaria, Melanoides, Cincinnatia and Corbicula, all other molluscs were collected as empty shells so we used the morphological species concept in this study. Therefore, shells of all species were photographed and described in detail. All shells were found to have recently died and many still retained operculae, so that we consider these shells represent their biocoenosis. Almost all extant subterranean snails were (and are) described only from empty shells because in many cases living populations were not accessible or available (Georgiev, 2013; Glöer et al., 2015; Grego et al., 2017). Of all species presented here, only members of the genus Galba Schrank, 1803 (Lymnaeidae) could not be identified at the species level due to shell convergence and the presence of many cryptic forms in this group (Alda et al., 2019). Only 1 duskysnail (Lyogyrus) specimen was found, so we refrain from describing a new species until further records are made. All other gastropods (except Mexithauma cf. quadripaludium) were found with sufficient specimens and their shells exhibited features that allow for a distinction on species level, although this often required scanning electron microscope images.

The taxonomy of the snails was based on the classification of Bouchet and Rocroi (2005) and biodiversity website MolluscaBase (MolluscaBase, 2019). For bivalves, we used the classification of Bieler et al. (2010). For morphological analysis, the shells and opercula were photographed and measured with a Zeiss AxioCamERc 5s camera attached to a Zeiss Stemi 2000-C microscope. Some specimens, especially their protoconchs as an essential diagnostic feature (Hershler, 1994; Perez & Minton, 2008), were examined in the Laboratorio de Biotecnología, Universidad Autónoma de Coahuila (UAC) in Torreón, Coahuila, using a HITACHI high performance FlexSEM 1000 scanning electron microscope.

To determine the status of conservation of the 23 species from Sabinas River, we used the NatureServe National Conservation Rank System described by Master et al. (2012). Many of the reported gastropods from the Sabinas River also occur in other sites in Mexico and their status of conservation has recently been assessed by Czaja et al. (2020), where the method is described in detail. Despite the new records presented here, only 1 of the previously reported Mexican species changed its status (Cochliopina riograndensis). The scale of the status used by NatureServe Conservation Rank System ranges from critically imperiled (N1) to secure (N5). The studied material is deposited at the Malacological Collection of the Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas de la (UJMC) of the Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango.

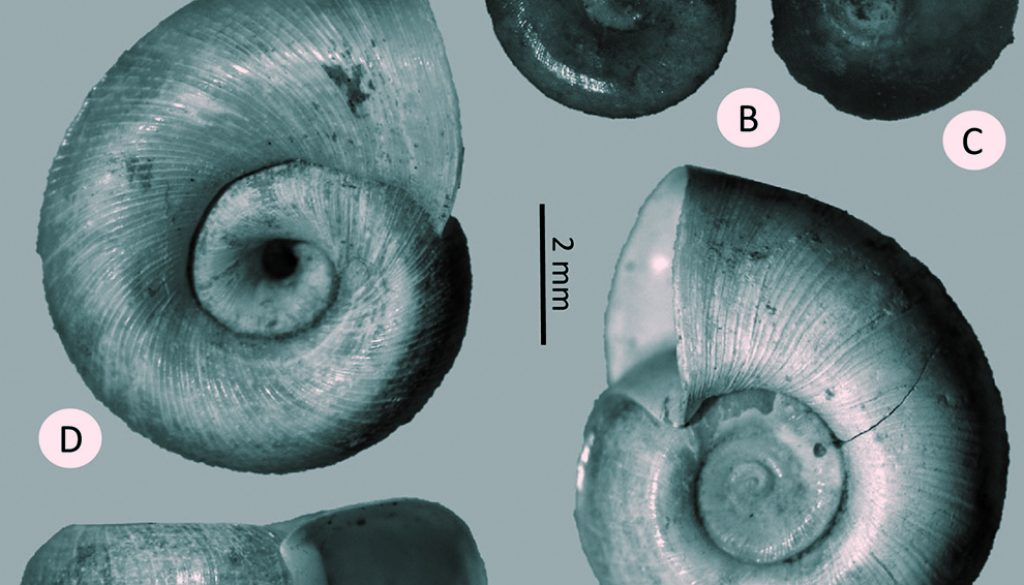

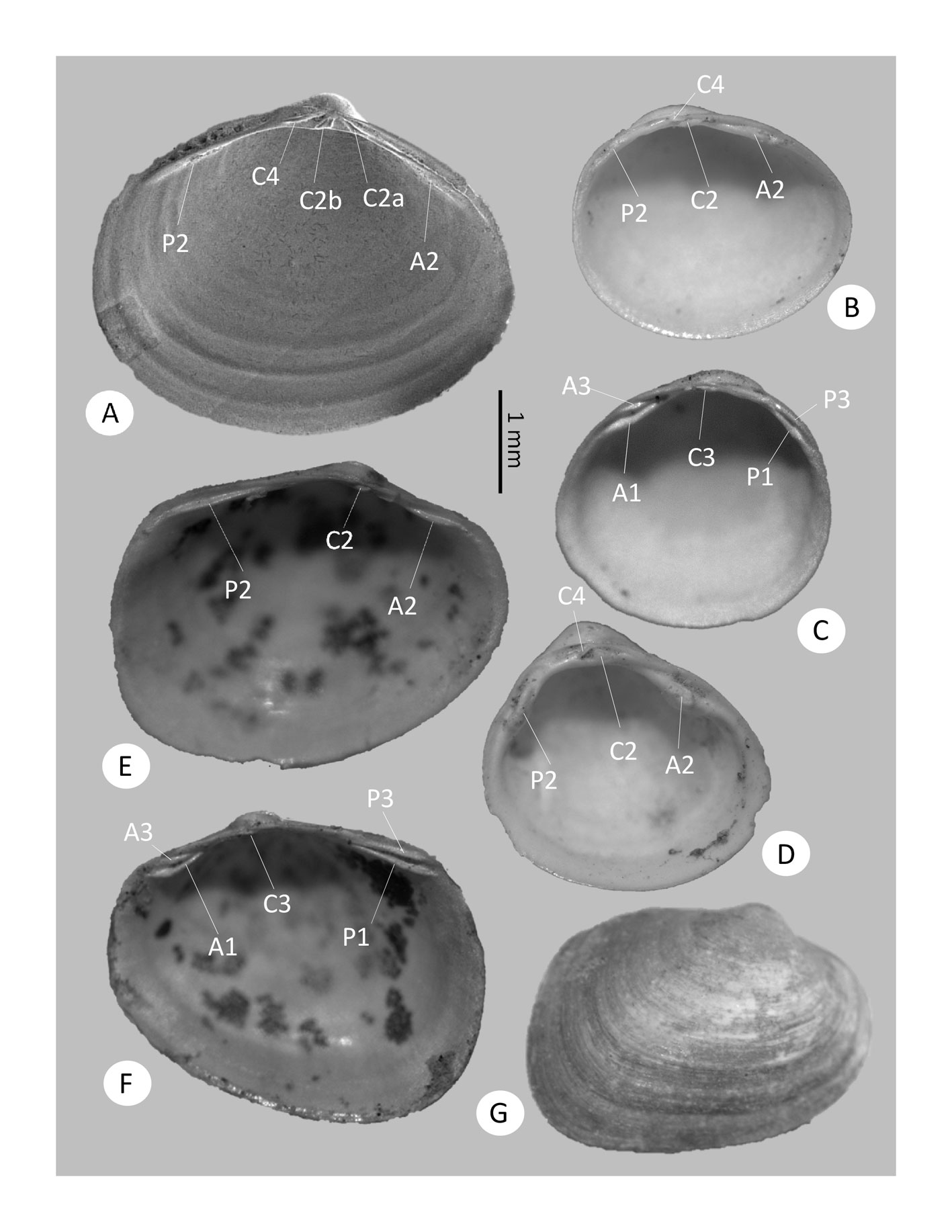

Abbreviations used: UJMC = University Juárez Malacological Collection; NatureServe-Rank-Conservation status: N1 = Critically imperiled, N2 = Imperiled, N3 = Vulnerable, N4 = Apparently secure, N5 = Secure, NH = Possibly extirpated, NX = Presumed extirpated, NU = Unable to assign rank, NQ = Questionable taxonomy. E = endemic, ECC endemic to Cuatro Ciénegas; Morphological terms: A1 = anterior lateral internal tooth, A2 = anterior lateral tooth, A3 = anterior lateral external tooth, C2 (a, b) = internal cardinal tooth, C3 = cardinal tooth, C4 = external cardinal tooth, P1 = posterior lateral internal tooth, P2 = posterior lateral tooth, P3 = posterior lateral external tooth.

Results

Class Bivalvia

Order Venerida

Superfamily Cyrenoidea Gray, 1840

Family Cyrenidae Gray, 1840

Genus Corbicula Megerle von Mühlfeld, 1811

Type species: Tellina fluminalis O. F. Müller, 1774

Corbicula fluminea (O. F. Müller, 1774) (invasive species)

(Fig. 3A)

Taxonomic summary

Description. The shell is oval to triangular in adult specimens, heavy, with concentric sulcations; hinge plate with 3 cardinal teeth (C2a, C2b, C4, Fig. 3A); lateral teeth straight to slightly curved and serrated; left valve has 2 long and thin lateral teeth, serrated on both sides (Fig. 3A); right valve with 2 pair of long lateral teeth, inner laterals more prominently serrated on medial surfaces than outer laterals.

Material examined: > 150 specimens (UJMC 450).

Table 1

Sampling sites in the Sabinas and Álamos River with coordinates.

|

Locality |

Coordinates |

|

|

1. Sabinas River, Ejido Nacimiento de los Mascogos II |

28°00’25’’ N |

101°42’46’’ W |

|

2. Sabinas River, Ejido Santa María |

27°58’37’’ N |

101°25’16’’ W |

|

3. Sabinas River, Ejido Sauceda del Naranjo |

27°57’24’’ N |

101°22’04’’ W |

|

4. Sabinas River, Ejido San Juan de Sabinas |

27°55’06’’ N |

101°17’54’’ W |

|

5. Álamos River, Ejido Paso del Coyote |

27°56’45’’ N |

101°15’19’’ W |

|

6. Sabinas River, Las Adjuntas (Rancho San Carlos) |

27°53’33’’ N |

101°11’41’’ W |

|

7. Sabinas River, Sabinas (Agua Prieta) |

27°49’38’’ N |

101°06’06’’ W |

|

8. Sabinas River, Las Cazuelas |

24°47’42’’ N |

101°03’14’’ W |

|

9. Sabinas River, La Vega |

27°41’35’’ N |

100°57’10’’ W |

Conservation status: N5.

Remarks. Unlike other bivalves from Sabinas River, C. fluminea occurs in many types of substrates such as mud, sand and gravel, albeit with different abundances (but prefers seemingly coarse sands and gravel substrate at the base of cobbles). Although the species is known from many sites in Coahuila (López-Altarriba et al., 2019), this is the first record of C. fluminea in the Sabinas River.

Order Sphaeriida Lemer, Bieler & Giribet, 2019

Superfamily Sphaerioidea Deshayes, 1855 (Rafinesque, 1820)

Family Sphaeriidae Deshayes, 1855 (Rafinesque, 1820)

Genus Pisidium C. Pfeiffer, 1821

Type species: Tellina amnica Müller, 1774 by subsequent designation (Gray, 1847)

Pisidium nitidum Jenyns, 1832

(Fig. 3B, C)

Taxonomic summary

Description. Shell oval in shape, all hinge teeth well developed, C3 slightly curved (Fig. 3C) and somewhat enlarged at posterior end, parallel with hinge, C2 and C4 fairly straight and near parallel, subequal in length, C2 longer (Fig. 3B), C4 thin; lateral teeth A1 and A2 large, P1 thin and straight, P3 and A3 shorter. The characteristic “peculiar striae…across the umbones”, stressed in the original description of Jenyns (1832, p. 305), are well visible only in juvenile specimens.

Material examined: 18 specimens (UJMC 451).

Conservation status: N5.

Remarks. Shells of this species are extremely variable in morphology so its taxonomy is therefore not well-defined (Kuiper et al., 1989). However, the hinge structure and especially the cardinal teeth are a useful diagnostic distinguishing feature. Euglesa casertana (Poli, 1791) (former Pisidium casertanum) and P. milium Held, 1836, show similar C3 tooth but, unlike P. nitidum, their respective C2 teeth are shorter than their C4. Molecular studies pointed out that P. nitidum and P. milium are sister species (Lee & Ó Foighil, 2003) which explains the mentioned similarities in the hinge structure.

Genus Euglesa Jenyns, 1832

Type species: Tellina pusilla Gmelin, 1791

Euglesa compressa (Prime, 1852)

(Fig. 3D)

Taxonomic summary

Description. Triangular in shape; hinge of the left valve long and curved, laterals short, C2 stump-like, resembling an inverted D, low, C4 short and thin, very slightly curved, directed toward cusp of P2, A2 high and strong, P2 less high, both with blunt, central cusps (Mackie & Huggins, 1983).

Material examined: 2 specimens (UJMC 452).

Conservation status: N4-N5.

Remarks. Herrington (1962) and Mackie and Huggins (1983) mentioned that Pisidium compressum (=Euglesa compressa) and P. ultramontanum have almost the same hinge characteristics. However, the last species, endemic to northeastern California and south-central Oregon, is rounded in outline, while shells of E. compressa are, according to the original description, more triangular (Prime, 1852, p. 219, Plate VI). There are few reports of this species in Mexico, but information about the exact location is lacking (Contreras-Arquieta, 2000). Fossil and sub-recent records have shown that this species had a wide and highly dense distribution in the region (Czaja, Estrada-Rodríguez et al., 2014; Czaja, Estrada-Rodríguez, Romero-Méndez & Orona-Espino, 2017).

Genus Eupera Bourguignat, 1854

Type species: Pisidium moquinianum Bourguignat, 1854

Eupera cubensis (Prime, 1865)

(Fig. 3E-G)

Taxonomic summary

Description: Shell oval to trapezoidal; lateral tooth P2 long and almost straight, C2 very short and high; A2 straight and half as long as P2 (Fig. 3E); P1 and P3 long and straight, C3 low, short and stump-like, A1 short, slightly curved (Fig. 3F); A3 low and short; inner faces of all laterals in right valve with numerous brown dots (Mackie & Huggins, 1983).

Material examined: 17 specimens (UJMC 453).

Conservation status: N4.

Remarks. The mottled fingernail clam is well characterized by the general rhomboidal form (Fig. 3G), delicate shells, 1 cardinal tooth in each valve and especially by the blackish-brown cluster of dots (Fig. 3E, F), notorious on the drawing of the original description by Prime (1865, p. 58. fig. 60). Contreras-Arquieta (2000) reported the occurrence of Eupera insignis Pilsbry (1925) (= synonym of E. cubensis) in Mexico but without any information on the exact location. According to our observations, this species seems to be common at least in northern Mexico (Coahuila, Durango, Chihuahua).

Class Gastropoda

Order Caenogastropoda (temporary name)

Superfamily Cerithioidea J. Fleming, 1822

Family Thiaridae Gill, 1871 (1823)

Genus Melanoides Olivier, 1804

Type species: Melanoides tuberculata (O. F. Müller, 1774)

Melanoides tuberculata (O. F. Müller, 1774) (Invasive species)

(Fig. 4A)

Taxonomic summary

Description. Shells turreted, dark brown with numerous reddish-brown streaks, exhibit great morphological variation related to size and, specifically, sculptures and ornaments; protoconch smooth; teleoconch with spiral grooves (Fig. 4A), some specimens with axial undulating ribs; with 6-10 slightly rounded whorls; aperture oval, operculum paucispiral with the nucleus near the base.

Material examined: > 400 specimens (UJMC 454).

Conservation status: N5.

Remarks. The first report of established populations of the invasive Red-Rim Melania in the Sabinas River is from 1994 (Contreras-Arquieta, 1998). The author described 3 sites on the Sabinas River (near the city of Múzquiz), where the density of M. tuberculata increased downstream. This increase is interpreted as a consequence of increasing eutrophic conditions downstream, caused by the pollution of the river by agriculture and mining.

Currently, the Red-Rim Melania is present in all sampled localities but especially abundant in sites 6-9. Although there is much evidence that this species can outcompete populations of native snails (Karatayev et al., 2009; Pointer, 1993), this has never been proven empirically. Our observations from the last 6 years in northern Mexico indicate decreases in native snail population. Especially, communities with hydrobid and cochliopid snails belong to the most affected groups by the presence of Melanoides (Czaja, Covich et al., 2019; personal unpublished data).

Order Littorinimorpha Golikov & Starobogatov, 1975

Superfamily Truncatelloidea Gray, 1840

Family Lithoglyphidae Tryon, 1866

Genus Phreatomascogos Czaja & Estrada-Rodríguez, 2019

Type species: Phreatomascogos gregoi Czaja & Estrada-Rodríguez, 2019

Phreatomascogos gregoi Czaja & Estrada-Rodríguez, 2019

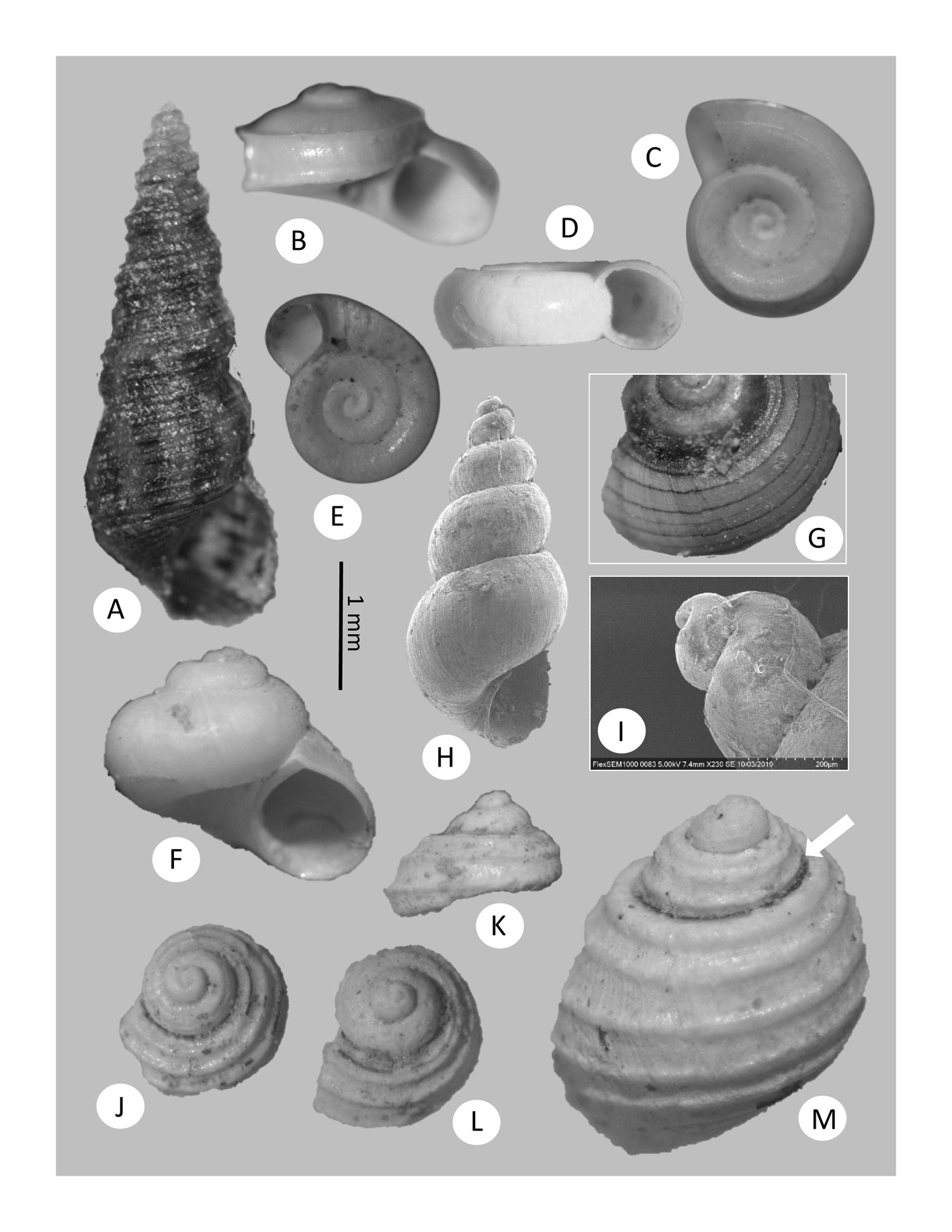

(Fig. 4B)

Taxonomic summary

Description. Shell small, valvatiform, varying in shape from (mostly) flat-trochoid to (rarely) low conical, height 0.65-0.99 mm, width 1.22-1.54 mm; umbilicus almost completely covered by a basal keel of the body whorl; protoconch smooth; teleoconch with 3¼ or fewer rounded whorls with less prominent axial growth lines, the border between protoconch and teleoconch approximately after 1.5 whorls (Czaja, Cardoza-Martínez et al., 2019, p. 93).

Material examined: 56 specimens (UJMC 400-407, UJMC 455).

Conservation status: N2.

Remarks. This recently described endemic species likely inhabits the interstitial space within the water-saturated underground gravel layer of the hyporheic zone (Czaja, Cardoza-Martínez et al., 2019).

Family Cochliopidae Tryon, 1866

Genus Balconorbis Hershler & Longley, 1986

Type species: Balconorbis uvaldensis Hershler & Longley, 1986

Balconorbis sabinasensis Czaja, Cardoza-Martínez & Estrada-Rodríguez, 2019

(Fig. 4C, D)

Taxonomic summary

Description. Shell minute, planispiral, width 1.51-1.81 mm, height 0.42-0.61 mm, with 3¼-3¾ whorls; protoconch smooth to slightly pitted, hidden in ventral view, has 1¼ whorls, first teleoconch whorl with strong and elevated axial growth lines which cross the spiral lines producing a square pattern, about 80 elevated spiral lines are present on the body whorl, body whorl with 1 or 2 keels, 1 keel usually stronger; aperture rounded to ovate (Czaja, Cardoza-Martínez et al., 2019, p. 95-96).

Material examined: 31 specimens (UJMC 410, 411, UJMC 456).

Conservation status: N2.

Remarks. The genus has 2 species distributed in Texas (Edwards Aquifer) and the Sabinas River (Coahuila), respectively. Both species have shells with a characteristic spiral structure that is unique among all other subterranean snails.

Genus Coahuilix Taylor, 1966

Type species: Coahuilix hubbsi Taylor, 1966

Coahuilix parrasense Czaja, Estrada-Rodríguez, Romero-Méndez, Ávila-Rodríguez,

Meza-Sánchez & Covich, 2017

(Fig. 4E)

Taxonomic summary

Description. Shell small, planispiral, 1.33-1.57 mm wide and 0.38-0.49 mm high, with 3-3¼ whorls, protoconch smooth to slightly pitted, hidden in apertural view, has 1¼ whorls, first teleoconch whorl with strong and elevated growth lines, subsequent whorls with fine growth lines, aperture rounded to ovate, apertural plane highly inclined (> 60°) relative to shell axis well inside the aperture 1 or (mostly) 2 tooth-like bulges (Czaja, Estrada-Rodríguez, Romero-Méndez, Ávila-Rodríguez et al., 2017, p. 230).

Material examined: 2 specimens (UJMC 416, 417).

Conservation status: N2.

Remarks. Coahuilix parrasense was described originally as a sub-fossil species from a dried-up stream near Parras de la Fuente, Coahuila. Posteriorly, this species was found in the Sabinas River, Coahuila and Nazas River, Durango (Czaja, Cardoza-Martínez et al., 2019; Czaja, Estrada-Rodríguez, Romero-Méndez & Orona-Espino, 2017).

Genus Cochliopina Morrison, 1946

Type species: Cochliopa riograndensis Pilsbry & Ferriss, 1906

Cochliopina riograndensis Pilsbry & Ferriss, 1906

(Fig. 4F, G)

Taxonomic summary

Description. Shell valvatiform, small, broadly heliciform, slightly olive to nearly transparent, up to 3.42 mm in width, openly umbilicate; with 4-4½ whorls, apical whorl with pitted structure; teleoconch nearly smooth or with spiral threads on the body whorl, 1 thread at the shoulder usually more prominent, with up to 10 dark brown pigmented bands (Fig. 4G), bands well visible especially on the threads, whorls moderately convex with deep sutures; the aperture is roundly ovate and angled toward the apex; peristome thin, inner lip partly fused to the penultimate whorl.

Material examined: 132 specimens (UJMC 457).

Conservation status: N3.

Remarks. Cochliopina riograndensis has been reported mostly as an epigean species but Alvear et al. (2020) mentioned that in Texas this snail also potentially occupies aquifer and hyporheic habitats. We found evidence also in the Sabinas River that C. riograndensis occurs in both interstitial and epigean environments. We suppose that this snail occurs in the area of study generally with 2 different ecophenotypic populations: 1) specimens with large shells with multiple brown pigmented bands, and 2) small shells without such distinctive spiral threads and nearly transparent.

Genus Juturnia Hershler, Liu & Stockwell, 2002

Type species: Durangonella coahuilae Taylor, 1966

Juturnia coahuilae (Taylor, 1966)

(Fig. 4H, I)

Taxonomic summary

Description. Shell 2.5-3.3 mm long, 1.2-1.4 mm wide, smooth, slender and turriform, protoconch smooth, teleoconch with 5½-6 strongly convex and smooth whorls, teleoconch sculpture with closely spaced growth lines, aperture nearly circular or rounded, inner lip thin to slightly thickened.

Material examined: 6 specimens (UJMC 458).

Conservation status: N2N3.

Remarks. Morphologically, the shells from the Sabinas River (Figs. 4H, I) are identical to those described by Taylor (1966, p. 184) and Hershler (1985, p. 83) from the type locality of this species and to Pleistocene material described from Coahuila (Czaja, Covich et al., 2019; Czaja, Palacios-Fest et al., 2014). Six transparent specimens of J. coahuilae were found in muddy sediments at the site 6 (Las Adjuntas). The fine and closely spaced growth lines on the teleoconch is characteristic feature of this species, which previously was known only as endemic to the spring complex of the Cuatro Ciénegas basin, Coahuila.

Genus Mexithauma Taylor, 1966

Type species: Mexithauma quadripaludium Taylor, 1966

Mexithauma cf. quadripaludium Taylor, 1966

(Fig. 4J, K)

Taxonomic summary

Description. Shell fragment with protoconch and following 3 whorls (without body whorl); protoconch smooth; teleoconch with 3 strong spiral cords, first cord beginning after approximately 1½ whorls (Fig. 4J), with remains of brownish periostracum bands above the first cord.

Material examined: 1 specimen, fragment (UJMC 459).

Conservation status: N2.

Remarks. Although only a fragment of the apex without body whorl was found, the general features and details of the shell are so characteristic that there is little doubt about the generic assignment of this fragment. We found various striking similar shell fragments at the Poza Azul, Cuatro Ciénegas basin (Fig. 4L). It seems that similar fragments arise because of (fish) predation, where the shells frequently break off exactly at the same point (Fig. 4J, L, M with arrow) between the body whorl and the second whorl. The preserved remains of brown bands on the shell fragment indicate that it is not a fossil but a recent specimen. Since they are made of organic material (thin periostracum), these bands are microbially degraded shortly after the death of the snail and thus are rarely preserved in the fossil record (own observations in Cuatro Ciénegas).

Since Mexithauma is a monotypic genus, the Sabinas shell fragment belongs most likely to this endemic form from Cuatro Ciénegas basin (M. quadripaludium Taylor). However, this cannot be concluded with complete certainty from the fragment itself, thus we considered it as not sufficient for an exact specific assignment. Pending further findings of living specimens, we tentatively assigned this species with a N2 rank.

Genus Pyrgophorus Ancey, 1888

Type species: Pyrgulopsis spinosus Call & Pilsbry, 1886

Pyrgophorus parvulus (Guilding, 1828)

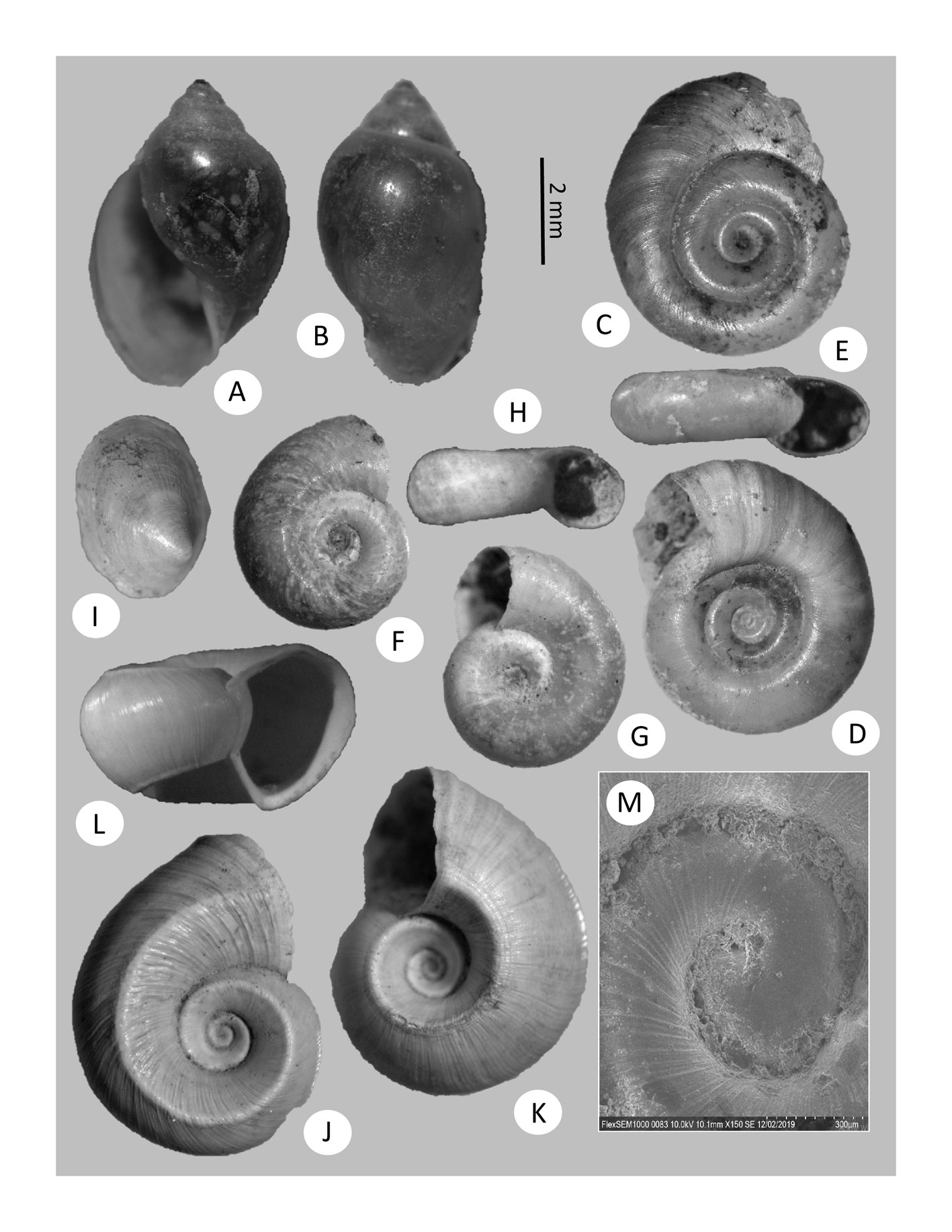

(Fig. 5A, B)

Taxonomic summary

Description. Shell with carinae modified to conical spines (Fig. 5A), spines darker than teleoconch, with 4-6 ½ whorls, first 2 whorls rounded and without spines on carinae, suture not deep; the lower part of the teleoconch with spiral striae which are visible on the penultimate and body whorl (Fig. 5B), body whorl large; of light green color, nearly white on apex; aperture roundly ovate, peristome not continuous, sharp.

Material examined: 28 specimens (UJMC 460).

Conservation status: N4.

Remarks. More than 30 nominal species were described from North, Central and South America based on shell-morphology and caused a taxonomic chaos in this genus (Hershler & Thompson, 1992). We have compared our material from Coahuila directly with shells of Pyrgophorus from many sites in Mexico, including Quintana Roo (approximately 2,500 km SE), and we did not detect any significant differences. Only P. cenoticus Grego, Angyal & Beltrán, 2019, a stygobiont species endemic to the Cenote Xoch in Yucatán, Mexico, has a distinguishable morphology of the shell (Grego et al., 2019). We agree with Hershler & Thompson (1992, with a list of synonyms) and considered that all other described Pyrgophorus forms belong (at least morphologically) to one polymorphic and wide distributed species. The first shells of such spinose morphology were collected in Jamaica and described as Paludina parvulus Guilding (1828). This designation seems to be the oldest name for such shells and, therefore, should be used.

Family Amnicolidae Tryon, 1863

Genus Lyogyrus Gill, 1863

Type species: Valvata pupoidea Gould, 1839

Lyogyrus sp.

(Fig. 5C-G)

Taxonomic summary

Description. Shell small, 1.62 mm in height and 1.14 mm in width, umbilicate, with faint growth lines; apex obtuse, protoconch depressed and flat (Figs. 5D, E), protoconch microsculpture of fine fimbriations (Fig. 5G); teleoconch with 4 extremely convex whorls (Fig. 5C-E), apical whorls flattened, body whorl slightly detached from the proceeding whorls, whorls sculptured with growth striations crossed by weak spiral lines on the lower part of the body whorl (Fig. 5E), with deeply impressed sutures, aperture small, almost perfectly rounded, 0.75 mm in diameter.

Material examined: 1 specimen (UJMC 461).

Conservation status: N2.

Remarks. Although only a single specimen was found, this shell from Sabinas provides congruent morphological evidence that it belongs to one of the genera in the family Amnicolidae. The general shape and details of the characteristic shell protoconch and teleoconch structure, visible on the SEM micrographs, show clearly that the specimen belongs to the genus Lyogyrus, probably a new species. Snails of the others members of the family in North America (Amnicola, Dasyscia, Colligyrus) have different shaped shells with larger apertures and less convex whorls.

The genus Lyogyrus has been little studied taxonomically and currently 9 species are recognized, differentiated merely by shell features. Only from L. pupoides, distributed in northern Atlantic Coastal drainage, and from Lyogyrus sp. (masked duskysnail, northwestern USA) exists DNA sequences (Liu et al., 2016). Our shell from the Sabinas River is similar to both shells of L. walkeri from Waubasacan Lake, Michigan, and Lyogyrus sp. Upsata Lake, Montana, illustrated by Liu et al. (2016, fig. 7A- C). However, there are detectable differences; the shell from Coahuila is approximately a third smaller in length and has other peristome features compared to those from USA. In the original description of L. walker (Pilsbry, 1898), Pilsbry especially emphasizes the “very convex” whorls and the “rather small” aperture. Both shell features apply exactly to our specimen. However, there are no molecular data of L. walker and, despite anatomical and molecular investigations, also the taxonomic status of the western masked duskysnail and its relation to L. walkeri have not been resolved (Liu et al., 2016). The authors recommend treating such snails as Lyogyrus sp., and we follow this recommendation for our shell from Sabinas until living specimens can be found. This is the first record of a member of the family Amnicolidae in Mexico.

Family Hydrobiidae Troschel, 1857

Genus Cincinnatia Pilsbry, 1891

Type species: Paludina integra Say, 1821

Cincinnatia integra (Say, 1821)

(Fig. 5H)

Taxonomic summary

Description. Shell sub-globose to ovate-conic, height 3.9-4.8 mm, with 4½ strongly inflated whorls, with pronounced shoulder, suture deeply impressed, apex acute, slightly convex, protoconch dome-like and smooth, aperture large and oval (detailed shell and opercula description by Hershler et al. [2011] and sub-fossil shells by Czaja, Estrada-Rodríguez, Romero-Méndez, Estrada-Arellano et al. [2017]).

Material examined: 10 specimens (UJMC 462).

Conservation status: N2N3.

Remarks. In USA, C. integra is a common species but its occurrence in the Sabinas River represents the second report from Mexico. Morphologically, our material from the Sabinas River is identical to shells from Rio La Ciénega, Veinte de Noviembre, San Luis Potosi, the other locality recorded for this species. Many fossil records shown that C. integra can be considered in Mexico as a Pleistocene relict (Czaja, Estrada-Rodríguez, Romero-Méndez, Estrada-Arellano et al., 2017).

Superorder Hygrophila Férussac, 1822

Superfamily Lymnaeoidea Rafinesque, 1815

Family Lymnaeidae Rafinesque, 1815

Genus Galba Schrank, 1803

Galba sp. (G. humilis species complex sensu Alda et al., 2019)

(Fig. 5I-K)

Taxonomic summary

Description. Shells up to 4.32 mm in height, protoconch and first whorl smooth, without visible microsculpture; teleoconch sculpture with many coarse and wavy growth lines (Figs. 5J, K) beginning after the first whorl; with 4-4½ whorls, whorls rounded and slightly shouldered, last whorl about half the length of the shell; aperture elongated and shouldered at its junction with body whorl.

Material examined: 12 specimens (UJMC 463).

Conservation status: N5.

Remarks. In their recent molecular revision of the genus, Alda et al. (2019) proposed that the genus Galba comprises 5 species (or species complexes) and that only Galba cousini from South America can be determined using shell morphology and internal anatomy. Since all the 5 species have shells morphologically indistinguishable from each other, we attributed our material tentatively to the G. humilis species complex sensu Alda et al. (2019).

Family Physidae Fitzinger, 1833

Genus Physella Haldeman, 1842

Physella acuta (Draparnaud, 1805)

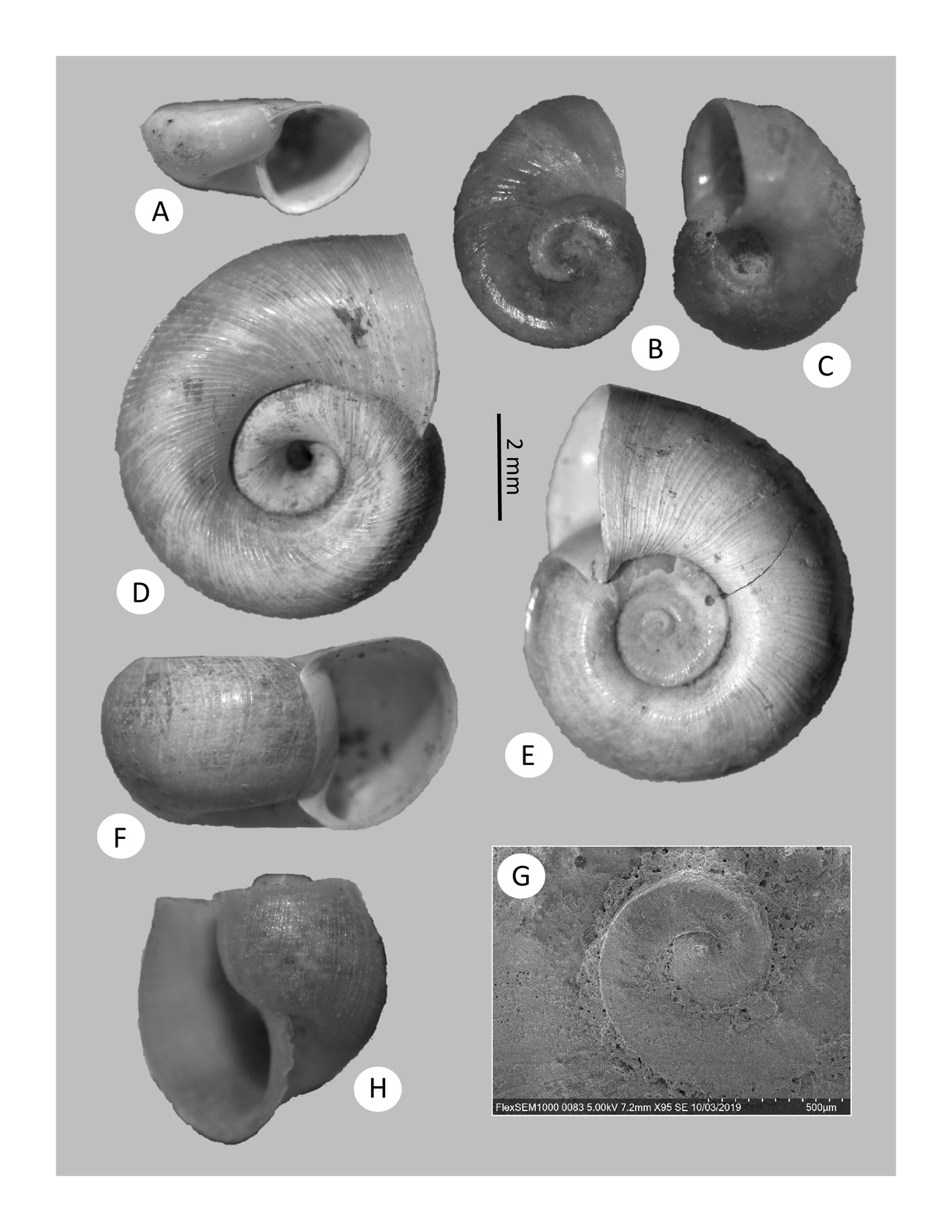

(Fig. 6A, B)

Taxonomic summary

Description. Shells up to 12.2 mm long but mainly smaller (4-6 mm), elongate-ovate; protoconch smooth, without visible sculpture, rounded; with 4-5 whorls, teleoconch with faint spiral growth lines, spire short with first whorls minute, the body whorl very large, suture slightly deep, body whorl approximately 85% of shell length; aperture large, ear-shaped, outer lip thin, inner lip closely appressed to the columellar region.

Material examined: 48 specimens (UJMC 464).

Conservation status: N5.

Remarks. Shells of Physella acuta based on topotypic specimens from France have been well-characterized by Paraense and Pointier (2003) and posteriorly, with North American specimens, by Wethington et al. (2009). Our material from the Sabinas River is identical with these shells and therefore we located it into this cosmopolitan species.

Family Planorbidae Rafinesque, 1815

Genus Biomphalaria Preston, 1910

Type species: Biomphalaria smithi Preston, 1910 (type by original designation)

Biomphalaria havanensis (L. Pfeiffer, 1839)

(Fig. 6C-E)

Taxonomic summary

Description. Shells medium sized (maximum diameter 9.07 mm), flattened, discoidal (flat spiral), ultradextral; with 3-4¾ rounded whorls, whorls increasing moderately in diameter; spire concave and flattened, umbilicus as a shallow depression (Fig. 6D); sculpture of fine lines of growth pronounced and irregular on the body whorl (Fig. 6C), whorls separated by deep sutures; aperture ovate, without apertural lamellae (Fig. 6E).

Material examined: 25 specimens (UJMC 465).

Conservation status: N5.

Remarks. The taxonomic history and systematics of the members of the genus Biomphalaria are long and confusing (DeJong et al., 2001). Similar shells to our material from Sabinas have been described from many sites in North and Central America as B. obstructa or B. havanensis. Morphologically, the 2 “species” are indistinguishable and recent molecular studies of Aguiar-Silva et al. (2014) and Rosser et al. (2016) confirmed that B. obstructa should be considered as younger synonym of B. havanensis.

Genus Gyraulus Charpentier, 1837

Type species: Planorbis albus O. F. Müller, 1774 (type by subsequent designation)

Gyraulus parvus (Say, 1817)

(Fig. 6F-H)

Taxonomic summary

Description. Shell small (up to 4.5 mm in diameter), discoidal, depressed, pale brown; with 2-3 whorls; with fine well visible growth-lines (Fig. 6E); spire flat, slightly depressed; umbilicus wide (Fig. 6F), shallow; all whorls are notorious from above and below (in contrast to Menetus dilatatus); aperture ovate, deflected below; outer and inner lip thin (Fig. 6H).

Material examined: 14 specimens (UJMC 466).

Conservation status: N4N5.

Remarks. The entire group with similar shelled forms such as G. parvus, G. deflectus and G. circumstriatus urgently needs a revision. Most similar to G. parvus is undoubtedly G. circumstriatus, but its shells have more whorls and the last one does not enlarge so rapidly like in G. parvus (Fullington, 1978).

Genus Hebetancylus Pilsbry, 1914

Type species: Ancylus moricandi Orbigny, 1837

Hebetancylus excentricus (Morelet, 1851)

(Fig. 6I)

Taxonomic summary

Description. Shell elliptical in form, apex behind the middle of the shell, distinctly to the right of the midline, blunt and smooth, without radial striations (Fig. 6I); anterior slope slightly convex, the posterior slope concave; prominent concentric growth lines (radial sculpture) below the apical region, mostly well visible but often also incomplete or missing.

Material examined: 15 specimens (UJMC 467).

Conservation status: N4N5.

Remarks. The original description of Morelet (1851) is very brief and without figures. The main shell features distinguishing this species from other limpets (Ferrissia, Laevapex) seem to be the distinctly right of the midline located apex (called by Morelet “lateralis”), and the clearly defined radial sculpture.

Genus Helisoma Swainson, 1840

Type species: Planorbis bicarinatus Say, 1819

Helisoma anceps (Menke, 1830)

(Fig. 6J-M)

Taxonomic summary

Description. Shell of moderate size, 8.2 mm in diameter, dextral, pale brown, 3¾ whorls, whorls carinated (2 prominent ridges) above and below (Fig. 6J, K) and rapidly enlarging, carinae rounded, upper carina at the center of the whorl; all whorls of the spire deeply immersed (unlike Planorbella trivolvis, see below); nucleus and the first third of the protoconch smooth (Fig. 6M), rest of protoconch with fine growth lines; umbilicus deep and narrow (Fig. 6K); teleoconch with regular, more or less radial riblets, which are, especially below the carina on the body whorl, crossed by wavy spiral threads (Fig. 6J); aperture ear-shaped, suddenly expanded (Fig. 6L).

Material examined: 6 specimens (UJMC 468).

Conservation status: N5.

Remarks. Shells of the Two-ridge Ramshorn snail are well differentiated from the following 2 planorbiid species by having 2 ridges (1 of each side) and a very deeply immersed spire and umbilicus and the above mentioned shell structure details. Helisoma ancept is a more northern species of cooler climate, very common throughout eastern USA (Fullington, 1978).

Genus Menetus H. Adams & A. Adams, 1855

Type species: Planorbis dilatatus Gould, 1841

Menetus dilatatus (A. Gould, 1841)

(Fig. 7A-C)

Taxonomic summary

Description. Shell small, ultradextral, flattened, discoidal (flat spiral), with few rapidly enlarging whorls; body whorl with less well-developed carina (keel), placed just above the center of the body; with 3 whorls, whorls rapidly increasing in size, sculpture of fine lines of growth; umbilicus deep (7C), all whorls visible only from above; aperture large, expanded; lips slightly thickened.

Material examined: 11 specimens (UJMC 469).

Conservation status: N3N4.

Remarks. In the present-day Menetus dilatatus has a broad distribution across the USA from Florida and Texas into Canada (Baker, 1945; Burch, 1989). Published records from Mexico are still known only from 2 sites in Zacatecas and Puebla (Albrecht et al., 2007; Thompson, 2011) and from streams of Coahuila (Nazas River) and Durango (Peñón Blanco River) (Czaja et al., 2020 and personal observations).

Genus Planorbella Haldeman, 1843

Type species: Planorbis campanulatus Say, 1821

Planorbella cf. trivolvis (Say, 1817)

(Fig. 7D-G)

Taxonomic summary

Description. Shell of medium size, brown, 11-15 mm in diameter, height about half of the diameter; spire deeply immersed but nucleus and first whorl slightly elevated (Fig. 7G, H), nucleus of protoconch smooth to slightly pitted (Fig. 7G), the remaining part of the protoconch with axial stripes; teleoconch with 4-4½ whorls, rapidly enlarging, inner 3 whorls nearly flat and, in contrast to H. anceps, not deeply immersed (Fig. 7E), right side deeply umbilicate so that only 2 whorls are visible (Fig. 7D), with 1 poorly developed carinae (Fig. 7E); aperture is angular above and rounded below, lower margin of aperture advanced beyond upper margin.

Material examined: 7 specimens (UJMC 470).

Conservation status: N5.

Remarks. Some species of the genus Planorbella such as P. duryi and P. trivolvis, are conchologically difficult to separate and the whole complex urgently needs a revision. The original description of Planorbis trivolvis of Say (1817) is very brief, so we also used the original description of 2 synonyms: Planorbis lentus Say, 1834 and Planorbis intertextus Sowerby, 1878. We described our material tentatively as P. cf. trivolvis due to the fact that the majority of the shell properties coincide with the descriptions (and figures) of the mentioned synonyms (in Say, 1834 as Planorbis lentus Say, 1834). It seems that this species differs from the similar shelled P. duryi in having characteristic regular radial riblets that reach almost to the nucleus (Fig. 7G) while the complete protoconch of P. duryi is almost smooth. If this is a sure diagnostic difference, it should to be shown in further studies.

Planorbella scalaris (Jay, 1839)

(Fig. 7H)

Taxonomic summary

Description. Shell small, height 3.02 mm, wide 2.83 mm, spire slightly raised above the body whorl when viewed from lateral (Fig. 7H), flat-topped; nucleus of protoconch smooth to slightly pitted, 160 µm in diameter, rest of the protoconch with fine growth lines; teleoconch with strong growth lines crossed by spiral lines; deeply umbilicated; lower margin of aperture not advanced beyond upper margin.

Material examined: 2 specimens (UJMC 471).

Conservation status: N4.

Remarks. The 2 shells from the Sabinas River resemble in all details shells of Planorbella scalaris, described originally as Paludina scalaris from the Everglades (Florida, USA) by Jay (1839, Plate 1, Figs. 8, 9). Similar shells have also been described frequently as P. duryi forma seminole but without any taxonomic legitimacy. Therefore, we considered that such shells should be denominated P. scalaris, unless the affiliation with P. duryi can be proved. Fossil scalaris-like Planorbella shells were already described from the late Pleistocene Paleolake Irritila, Coahuila, approximately 150 km southern of the area of study, by Czaja, Estrada-Rodríguez et al. (2014). The Mesa Rams-horn was described originally as endemic to Florida marshes and lakes in the central and southern part of the peninsula, particularly from the Everglades, South Florida (Baker, 1945; Burch, 1989; Thompson, 1999). Nevertheless, the abundance of fossil records from the region shows that this species can be considered as a native form in the Sabinas River (Czaja, Palacios-Fest et al., 2014).

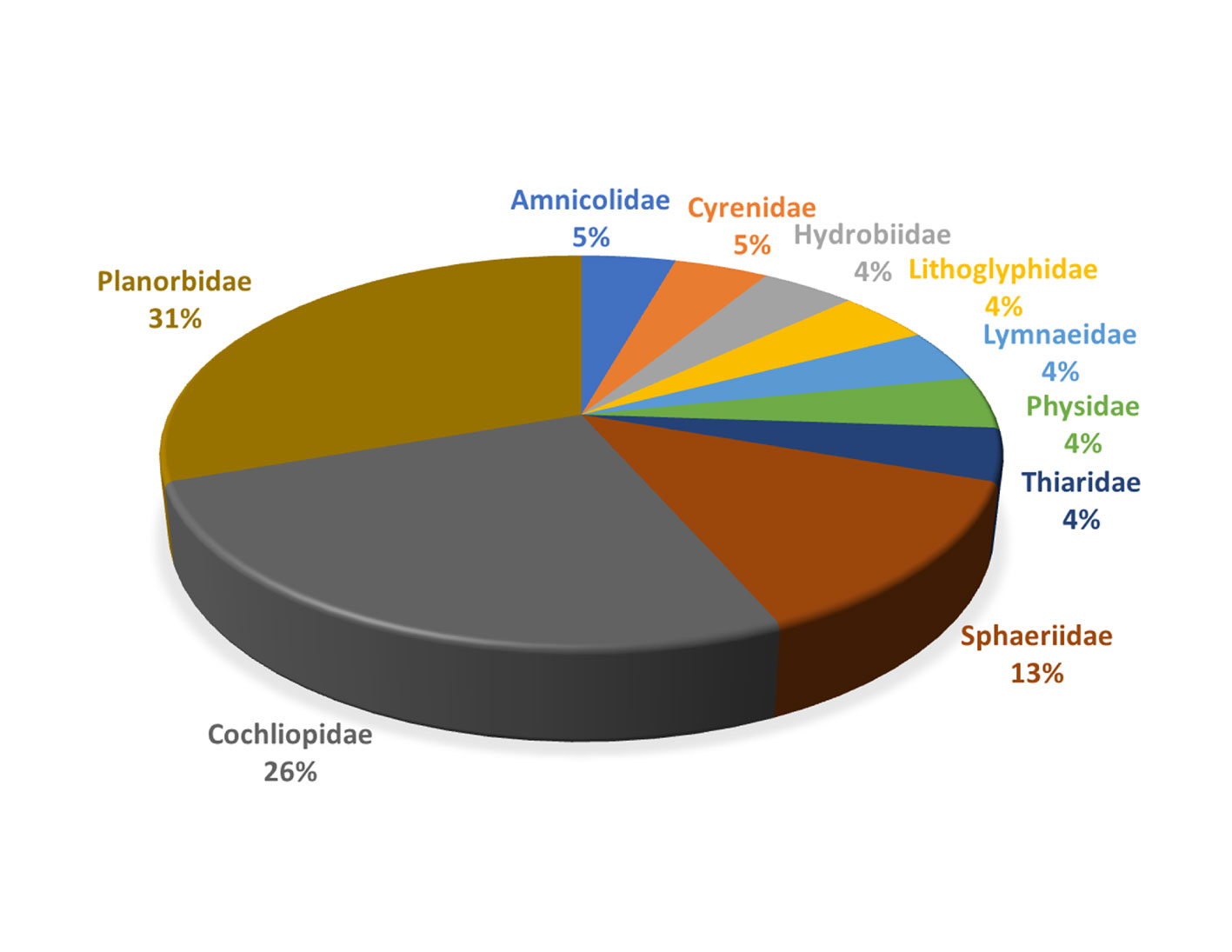

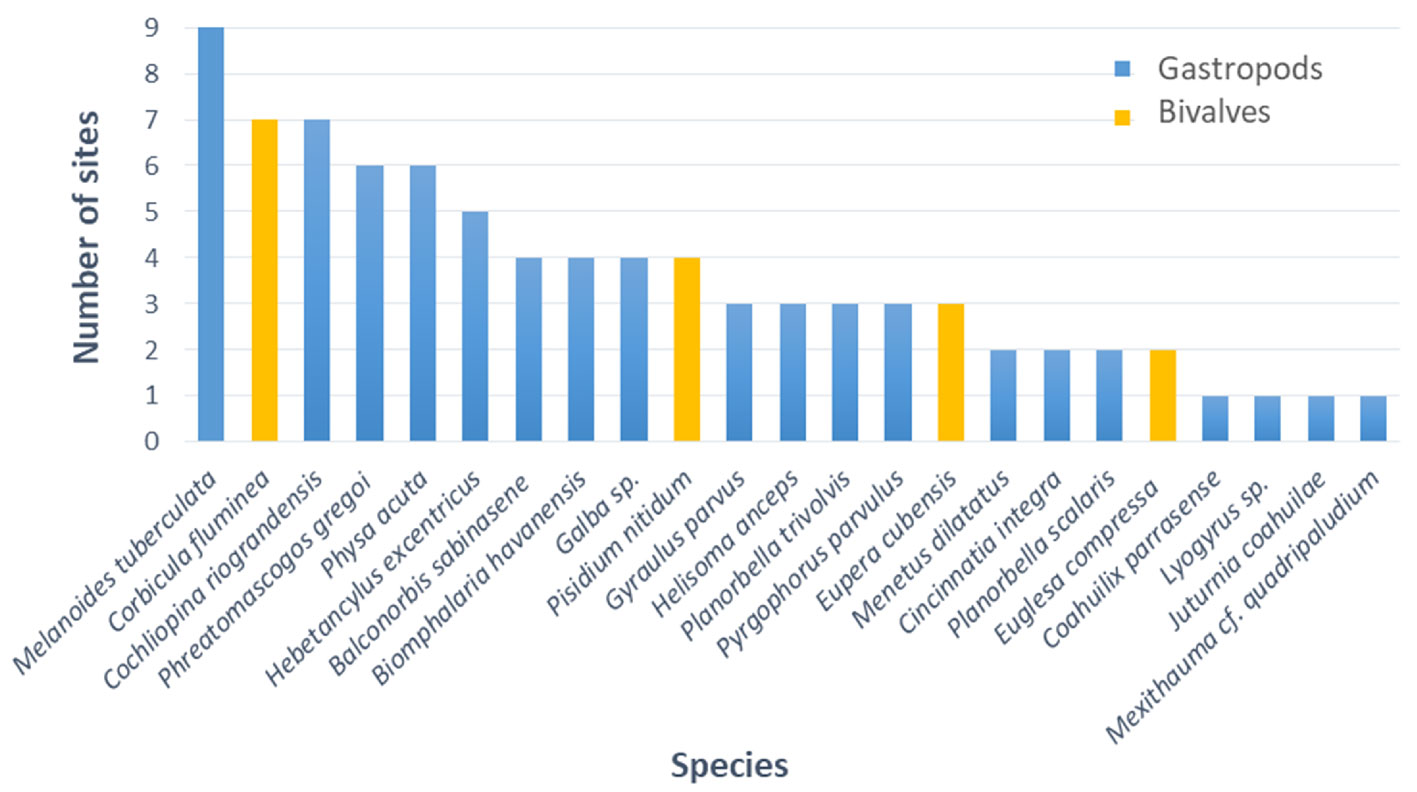

Molluscan diversity and species richness. From 9 sites, the occurrence of 23 (19 gastropods and 4 bivalves) species are reported (Table 2). Of the 14 mollusc families present in Mexico, 10 occur in the area of study. Planorbidae is the most diverse family with 7 species, followed by Cochliopidae (6) and Sphaeriidae (3) (Fig. 8). In total, 22 genera are present where Planorbidae and Cochliopidae dominate each with 6 genera, followed by Sphaeriidae (3). The malacofauna contains 1 endemic genus (Phreatomascogos) and 2 endemic species belong to cochliopiid and lithoglyphiid families. Lyogyrus sp. (possibly a new species) is the first member of the Amnicolidae family found in Mexico. Finally, 2 invasive species were found (Melanoides tuberculata and C. fluminea).

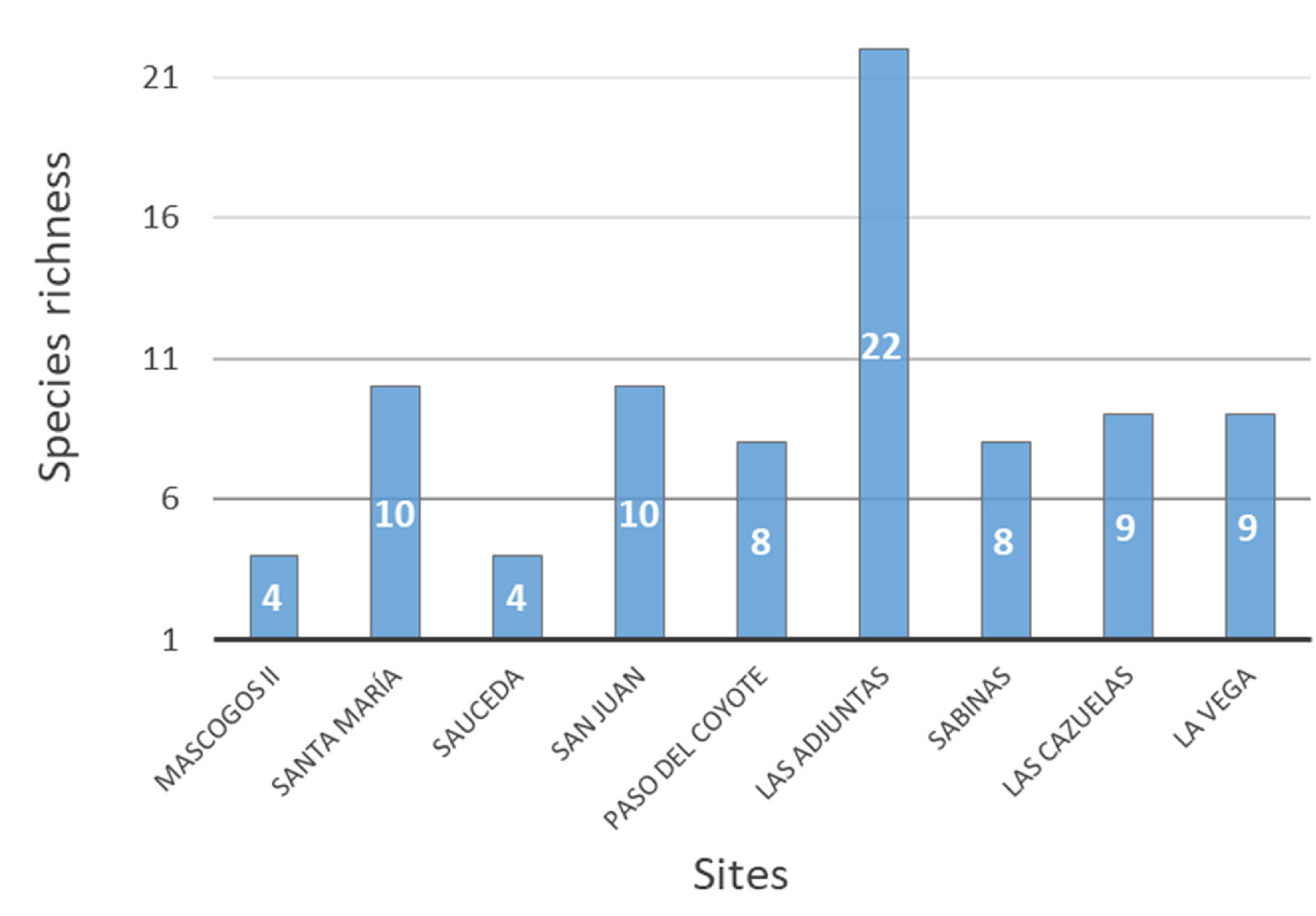

Species richness per site (Fig. 9) ranged from 4 to 22 and was greatest at site 6 (Las Adjuntas), where 22 of the 23 species were found. At other sites the diversity is relatively low (4-10 species). Melanoides tuberculata is the most abundant gastropod and was present at all 9 sites, followed by C. riograndensis (7 sites), P. gregoi (6) and H. excentricus (5) (Fig. 10). Coahuilix parrasense, J. coahuilae, Lyogyrus sp. and M. cf. quadripaludium were found only at 1 site, and the last 2 species with a single specimen. Corbicula fluminea is by far the most common bivalve present at 7 sites followed by P. nitidum (4).

Table 2

List of molluscan species from Sabinas River basin with their conservation rank and site of occurence. E = Endemic, ECC = endemic in Cuatro Ciénegas; NatureServe-Rank-Conservation status: N1 = critically imperiled, N2 = imperiled, N3 = vulnerable, N4 = apparently secure, N5 = secure; 1-9 = number of the studied sites (see Table 1).

|

Family |

Species |

Endemic |

N-Rank |

Site |

|

Cyrenidae |

Corbicula fluminea (O. F. Müller, 1774) |

─ |

N5 |

3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 |

|

Sphaeriidae |

Pisidium nitidum Jenyns, 1832 |

─ |

N5 |

2, 3, 6, 8 |

|

Sphaeriidae |

Euglesa compressa (Prime, 1852) |

─ |

N4N5 |

2, 6 |

|

Sphaeriidae |

Eupera cubensis (Prime, 1865) |

─ |

N3 |

4, 6, 8 |

|

Thiaridae |

Melanoides tuberculata (O. F. Müller, 1774) |

─ |

N5 |

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 |

|

Lithoglyphidae |

Phreatomascogos gregoi Czaja & Estrada-Rodríguez, 2019 |

E |

N2 |

1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 9 |

|

Cochliopidae |

Balconorbis sabinasensis Czaja, Cardoza-Mart. & Estrada-Rodríg., 2019 |

E |

N2 |

2, 5, 6, 9 |

|

Cochliopidae |

Coahuilix parrasense Czaja et al. 2017 |

E |

N2 |

6 |

|

Cochliopidae |

Cochliopina riograndensis Pilsbry and Ferriss, 1906 |

─ |

N3 |

2,4,5,6,7,8,9 |

|

Cochliopidae |

Juturnia coahuilae (Taylor, 1966) |

(ECC) |

N2 |

6 |

|

Cochliopidae |

Mexithauma cf. quadripaludium Taylor, 1966 |

(ECC) |

N2 |

5 |

|

Cochliopidae |

Pyrgophorus parvulus (Guilding, 1828) |

─ |

N4 |

6, 7, 8, 9 |

|

Amnicolidae |

Lyogyrus sp. |

─ |

N2 |

6 |

|

Hydrobiidae |

Cincinnatia integra (Say, 1821) |

─ |

N2N3 |

2, 4 |

|

Lymnaeidae |

Galba sp. |

─ |

N5 |

4, 6, 7, 9 |

|

Physidae |

Physella acuta (Draparnaud, 1805) |

─ |

N5 |

2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 9 |

|

Planorbidae |

Biomphalaria havenensis (L. Pfeiffer, 1839) |

─ |

N5 |

1, 2, 6, 8 |

|

Planorbidae |

Gyraulus parvus (Say, 1817) |

─ |

N4N5 |

2, 4, 6, 8 |

|

Planorbidae |

Hebentancylus excentricus (Morelet, 1851) |

─ |

N5 |

1, 4, 5, 6. 7 |

|

Planorbidae |

Helisoma anceps (Menke, 1830) |

─ |

N5 |

2, 4, 6 |

|

Planorbidae |

Menetus dilatatus (Gould, 1841) |

─ |

N3N4 |

4, 6, 8 |

|

Planorbidae |

Planorbella cf. trivolvis (Say, 1817) |

─ |

N5 |

6, 7, 9 |

|

Planorbidae |

Planorbella scalaris (Jay, 1839) |

─ |

N4 |

2, 9 |

As an important result of our study, we consider the new records of members of the genera Coahuilix, Juturnia and Mexithauma. Previously, these gastropods had been known as endemic species exclusively from the Cuatro Ciénegas basin. Other, extremely rare species in Mexico, such as C. integra, C. riograndensis and the clam E. cubensis have their habitat in the Sabinas River.

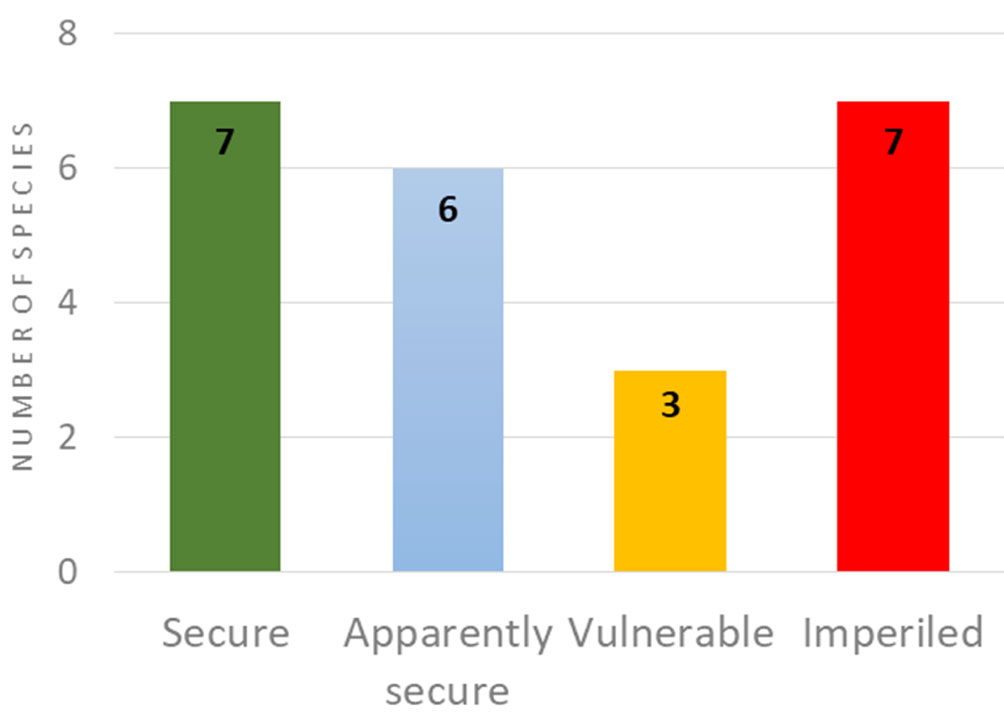

Conservation status. We assessed the new records of J. coahuilae, Lyogyrus sp. and M. cf. quadripaludium tentatively as (at least) imperiled because these species were found with few specimens and only at 1 site. According to our assignation, none of the species present at the Sabinas River are critically imperiled, but 7 (31.8%) are imperiled, 3 (13.1%) are vulnerable and only 13 (56.1%) are currently stable (Fig. 11; Table 2). This means, that 44% of the species from the Sabinas River are in some status of imperilment. It is noteworthy that all 7 imperiled gastropods are hydrobioid species (Cochliopidae, Hydrobiidae and Amnicolidae) and all endemics belong to this imperiled group. This indicates clearly that the hydrobioid snails should be in a special focus of conservation efforts. However, to date only 2 species (M. quadripaludium and J. coahuilae) are listed as endangered by the Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Mexican Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources) (Semarnat, 2010). The locality with the highest number of imperiled species is site 6 (Las Adjuntas), where 5 of the 7 endangered gastropods occur.

Discussion

Although, so far, only a small part of the Sabinas River and 1 site at the Álamos River were studied, the 23 species of molluscs reported is substantial. No other site in Northern Mexico has a richer record in number of species; including the well-studied Cuatro Ciénegas Basin, where 20 species occur in total. Of the 14 gastropod freshwater families reported in Mexico (Czaja et al., 2020), 8 occur in the Sabinas River, thus, this area can be considered an important refuge for rare species.

Today the Cuatro Ciénegas Basin and the Sabinas River have merely a temporary connection due to the Monclova River, which is an intermittent stream (own observations). Genetic flow between snail populations is at least temporarily limited or does not take place, so that allopatric evolutionary divergence processes in snails are very likely (2 different species of the genus Coahuilix). Some species such as P. gregoi, B. sabinasensis, C. parrasense and Lyogyrus sp. (not present in Cuatro Ciénegas Basin) developed special habitat adaptations in Sabinas River that limit their distribution to small areas in subterranean environments (Czaja, Cardoza-Martínez et al., 2019). Since it is a lotic environment, the assignment of the individual species to the particular site is fraught with uncertainty. A possible transport of the organisms must be expected.

The assigned conservation ranks imply that at least 10 species from Sabinas River are of special conservation significance (Fig. 11), especially, the recently described subterranean species P. gregoi, B. sabinasensis, C. parrasense and J. coahuilae. Stygobiont snails belong worldwide to the most vulnerable freshwater gastropods (Johnson et al., 2013; Böhm et al., 2020). Also, Lyogyrus sp., belongs most likely to the same group and we suspect that this snail lives in Sabinas River in the same subterranean habitat with the mentioned stygobionts.

There are many reports from North America about negative ecological impacts of M. tuberculata in invaded systems so that the sole presence of this species should already be an alarm signal (Contreras-Arquieta, 1998; Naranjo-García & Castillo-Rodríguez, 2017). In all study sites, especially those with sandy sediments, the invasive M. tuberculata is present. However, in more polluted habitats (sites 8 and 9) with strong agriculture activity we observed that the level of abundance increases. We observed that in such human impacted sites Melanoides is more common by simultaneous reduction, or total absence, of hydrobioid snails (Czaja, Covich et al., 2019).

Due to the limited number of samples from different habitats, we did not perform a species abundance analysis, however, in all sites Melanoides and Corbicula are by far dominant while all other species, especially the hydrobioids (except Cochliopina), are rare. Since we have no historical data, we cannot directly prove a positive relationship between the occurrence of Melanoides and low densities of the native species. Nevertheless, such a relationship in the Sabinas River is quite likely, considering the many reports from similar sites in northern Mexico (Contreras-Arquieta, 1998). The key point for the native species of the Sabinas River is probably not the sole presence of the invasive forms but the combination with the degree of pollution (eutrophication) of the sites. An aquatic ecosystem can apparently “amortize” an invasion, but with a simultaneous heavy pollution (eutrophication), the less tolerant native forms are disadvantaged.

Like Melanoides, C. fluminea is also one of the most important invasive species, whose populations underwent massive expansion in a short time, creating negative impacts on native bivalves in many aquatic ecosystems of North America and Europe (Beran, 2006; Ilarri & Sousa, 2012; Sousa et al., 2008). Characteristic of affected habitats with the presence of the Asian clam, is the lack of bivalves of the genus Sphaerium Scopoli, 1777, and large unionid mussels. Such displacements of large native bivalves are reported from many sites with C. fluminea in North America (McMahon, 2002; Sousa et al., 2008; Vaughn & Hakenkamp, 2001). Such large bivalves are seemingly missing in the Sabinas River, although they are very common in subfossil molluscan assemblages in neighboring areas (Czaja et al., 2014; own observations). So far, C. fluminea has not been detected within Cuatro Ciénegas but it does occur just outside of the basin in the Rio Salado de Nadadores (Dinger et al., 2005). Why C. fluminea has not invaded the springs of Cuatro Ciénegas is unclear.

If the heavy human impact downstream continues, we expect further expansion of both non-native species, with strong changes in the native molluscan assemblages for the Sabinas River area, especially bivalves. Because biological invasions are generally irreversible (Vander-Zanden & Olden, 2008), the implementation of management actions is urgent, such as monitoring, further research on the invasive species, identifying their undesired consequences and the determination of site vulnerability. However, the first step in this process must be the integration of the mentioned 7 imperiled species from the Sabinas River into the list of NOM-059 of the Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Mexican Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources) (Semarnat, 2010).

Acknowledgements

This investigation is part of the mega-project “Ecological restoration on the riparian vegetation of the Natural Resources Protection Area, Upper Basin of the National Irrigation District 004 Don Martín”, funded by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and implemented by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and the National Commission of Natural Protected Areas (Conanp). We thank especially Cecilio Arreola Chapa and Yabid Alexander Sanchez-Montañez for sampling and other fieldwork. We are grateful to Alan P. Covich (Georgia, USA) and Richard Dale Bledsoe (UJED, Gómez Palacio, Durango) for their help with English proof. We dedicate this article to our co-author, colleague, and friend, Dr. Ulises Romero-Méndez(†), who passed away unexpectedly during the edition of this paper. Rest in peace.

References

Aguiar-Silva, C., Mendonça, C. L., da Cunha Kellis-Pinheiro, P. H., Mesquita, S. G., Carvalho, O. & Caldeira, R. L. (2014). Evaluation and updating of the Medical Malacology Collection (Fiocruz-CMM) using molecular taxonomy. SpringerPlus, 3, 446.

Albrecht, C., Kuhn, K., & Streit, B. (2007). A molecular phylogeny of Planorboidea (Gastropoda, Pulmonata): insights from enhanced taxon sampling. Zoologica Scripta, 36, 27–39.

Alda, P., Lounnas, M., Vázquez. A. A., Ayaqui, R., Calvopiña, M., Celi-Erazo, M. et al. (2019). Systematics and geographical distribution of Galba species, a group of cryptic and worldwide freshwater snails. BioRxiv, 647867. Preprint.

Alvear, D., Diaz, P. H., Gibson, J. R., Hutchins, B., Schwartz, B., & Perez, K. E. (2020). Expanding the known ranges of the endemic, phreatic snails (Mollusca, Gastropoda) of Texas, USA. Freshwater Mollusk Biology and Conservation, 23, 1–17.

Baker, F. C. (1945). The molluscan family Planorbidae. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press.

Beran, L. (2006). Spreading expansion of Corbicula fluminea (Mollusca: Bivalvia) in the Czech Republic. Heldia, 6, 187–192.

Bieler, R., Carter, J. G., & Coan, E. V. (2010). Classification of Bivalve families. In P. Bouchet, & J. P. Rocroi (Eds.), Nomenclator of Bivalve Families (pp. 113–133). Malacologia, 52, 1–184.

Böhm, M., Dewhurst-Richman, N. I., Seddon, M., Ledger, S. E., Albrecht, C., Allen, D. et al. (2020). The conservation status of the world’s freshwater molluscs. Hydrobiologia, 2020, 1–24.

Bouchet, P., & Rocroi, J. P. (2005). Classification and Nomenclator of Gastropod Families. Malacologia, 47, 1–397.

Burch, J. B. (1989). North American freshwater snails. Hamburg, Michigan: Malacological Publications.

Contreras-Arquieta, A. (1998). New records of the snail Melanoides tuberculata (Müller, 1774) (Gastropoda: Thiaridae) in the Cuatro Ciénegas basin, and its distribution in the state of Coahuila, Mexico. The Southwestern Naturalist, 43, 283–286.

Contreras-Arquieta, A. (2000). Bibliografía y lista taxonómica de las especies de moluscos dulceacuícolas en México. Mexicoa, 2, 40–53.

Czaja, A., Cardoza-Martínez, G. F., Meza‑Sánchez, I. G., Estrada-Rodríguez, J. L., Sáenz‑Mata, J., Becerra-López, J. L. et al. (2019). New genus, two new species and new records of subterranean freshwater snails (Caenogastropoda; Cochliopidae and Lithoglyphidae) from Coahuila and Durango, Northern Mexico. Subterranean Biology, 29, 89–102. https://doi.org/10.3897/subtbiol.29.34123

Czaja, A., Covich, A. P., Estrada-Rodríguez, J. L., Romero-Méndez, U., Sáenz-Mata, J., Meza-Sánchez, I. G. et al. (2019). Fossil freshwater gastropods from northern Mexico – A case of a “silent” local extirpation, with the description of a new species. Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 71, 609–629. https://doi.org/10.18268/bsgm2019v71n3a2

Czaja, A., Estrada-Rodríguez, J. L., & Romero-Méndez, U. (2014). Freshwater mollusks of the Valley of Sobaco, Coahuila, Northeastern Mexico – a subfossil ecosystem similar to Cuatrociénegas. Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 66, 459–469. https://doi.org/10.18268/bsgm2014v66n3a4

Czaja, A., Estrada-Rodríguez, J. L., Romero-Méndez, U., Ávila-Rodríguez, V., Meza-Sánchez, I. G., & Covich, A. P. (2017). New species and records of phreatic snails (Caenogastropoda: Cochliopidae) from the Holocene of Coahuila, Mexico. Archiv für Molluskenkunde, 146, 227–232. https://doi.org/10.1127/arch.moll/146/227-232

Czaja, A., Estrada-Rodríguez, J. L., Romero-Méndez, U., Estrada-Arellano, J. R., & González-Zamora, A. (2017). Primer registro fósil del gasterópodo Cincinnatia (Hydrobiidae: Nymphophilinae) en México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 88, 912–917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmb.2017.10.025

Czaja, A., Estrada-Rodríguez, J. L., Romero-Méndez, U., & Orona-Espino, A. (2017). Two new subfossil species of springsnails (Hydrobiidae: Pyrgulopsis) from north Mexico and their relation with extant species from Cuatrociénegas. Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 69, 199–208. https://doi.org/10.18268/bsgm2017v69n1a9

Czaja, A., Meza-Sánchez, I. G., Estrada-Rodríguez, J. L., Romero-Méndez, U., Sáenz‑Mata, J., Ávila-Rodríguez, V. et al. (2020). The freshwater snails (Mollusca: Gastropoda) of Mexico: updated checklist, endemicity hotspots, threats and conservation status. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 91, 1–22. e912909 https://doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2020.91.2909

Czaja, A., Palacios-Fest, M. R., Estrada-Rodríguez, J. L., Romero-Méndez, U., & Alba-Ávila, J. A. (2014). Inland Dunes mollusks fauna from the Paleolake Irritila in the Comarca Lagunera, Coahuila, Northern Mexico. Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 66, 541–551. https://doi.org/10.18268/bsgm2014v66n3a9

DeJong, R. J., Morgan, J. A. T., Paraense, W. L., Pointier, J. P., Amarista, M., Ayeh-Kumi, P. F. et al. (2001). Evolutionary relationships and biogeography of Biomphalaria (Gastropoda: Planorbidae) with implications regarding its role as host of the human bloodfluke, Schistosoma mansoni. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 18, 2225–2239. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals

Dinger, E. C., Cohen, A. C., Hendrickson, D. A., & Marks J. C. (2005). Aquatic invertebrates of Cuatro Ciénegas, Coahuila, México: natives and exotics. Southwestern Naturalist, 50, 237–246.

Dudgeon, D. (2020). Freshwater biodiversity. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Fullington, R. W. (1978). The recent and fossil freshwater gastropod fauna of Texas (PhD. Dissertation). North Texas State University, Denton, Texas.

Georgiev, D. (2013). Catalogue of the stygobiotic and troglophilous freshwater snails (Gastropoda: Rissooidea: Hydrobiidae) of Bulgaria with descriptions of 5 new species. Ruthenica, 23, 59–67.

Glöer, P., Grego, J., Erőss, Z. P., & Fehér, Z. (2015). New records of subterranean and spring molluscs (Gastropoda: Hydrobiidae) from Montenegro and Albania with the description of 5 new species. Ecologica Montenegrina, 4, 70–82.

Grego, J., Angyal, D., & Liévano-Beltrán, L. A. (2019). First record of subterranean freshwater gastropods (Mollusca, Gastropoda, Cochliopidae) from the cenotes of Yucatán state. Subterranean Biology, 29, 79–88. https://doi.org/10.3897/subtbiol.29.32779

Grego, J., Glöer, P., Erőss, Z. P., & Fehér, Z. (2017). Six new subterranean freshwater gastropod species from northern Albania and some new records from Albania and Kosovo (Mollusca, Gastropoda, Moitessieriidae and Hydrobiidae). Subterranean Biology, 23, 85–107. https://doi.org/10.3897/subtbiol.23.14930

Herrington, H. B. (1962). A revision of the Sphaeriidae of North America (Mollusca: Pelecypoda). Ann Arbor, Michigan: Miscellaneous publications, Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan.

Hershler, R. (1985). Systematic revision of the Hydrobiidae (Gastropoda: Rissoacea) of the Cuatro Cienegas Basin, Coahuila, Mexico. Malacologia, 26, 31–123.

Hershler, R. (1994). A review of the North American freshwater snail genus Pyrgulopsis (Hydrobiidae). Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology, 554, 1–115.

Hershler, R., & Thompson, F. G. (1992). A review of the aquatic gastropod subfamily Cochliopinae (Prosobranchia: Hydrobiidae). Malacological Review, (Suppl. 5), 1–140.

Hershler, R., Thompson, F. G., & Liu, H. P. (2011). A large range extension and molecular phylogenetic analysis of the monotypic North American aquatic gastropod genus Cincinnatia (Hydrobiidae). Journal of Molluscan Studies, 77, 232–240.

Ilarri, M., & Sousa, R. (2012). Corbicula fluminea Müller (Asian Clam). In Francis, R. A. (Ed.), A handbook of global freshwater invasive species (pp. 173–183). London: Earthscan.

Jay, J. C. (1839). A catalogue of shells, arranged according to the Lamarckian system; together with descriptions of new or rare species, contained in the collection of John C. Jay, M.D. New York: Wiley & Putnam.

Jenyns, L. (1832). A monograph on the British species of Cyclas and Pisidium. Cambridge, U.K.: Transactions of the Cambridge Philosophical Society.

Johnson, P. D., Bogan, A. E., Brown, K. M., Burkhead, N. M., Cordeiro, J. R., Garner, J. T. et al. (2013). Conservation status of freshwater gastropods of Canada and the United States: Fisheries, 38, 247–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/03632415.2013.785396

Karatayev, A. Y., Burlakova, L. E., Karatayev, V. A., & Padilla, D. K. (2009). Introduction, distribution, spread, and impacts of exotic freshwater gastropods in Texas. Hydrobiologia, 619, 181–194.

Kuiper, J. G. J., Økland, K. A., Knudsen, J., Koli, L., von Proschwitz, T., & Valovirta, I. (1989). Geographical distribution of the small mussels (Sphaeriidae) in North Europe (Denmark, Faroes, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden). Annales Zoologici Fennici, 26, 73–101.

Lee, T., & Ó Foighil, D. (2003). Phylogenetic structure of the Sphaeriinae, a global clade of freshwater bivalve molluscs, inferred from nuclear (ITS-1) and mitochondrial (16S) ribosomal gene sequences. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 137, 245–260.

Liu, H. P., Marceau, D., & Hershler, R. (2016). Taxonomic identity of two amnicolid gastropods of conservation concern in lakes of the Pacific Northwest of the USA. Journal of Molluscan Studies, 82, 464–471.

López-Altarriba, E., Garrido-Olvera, L., Benavides-González, F., Blanco-Martínez, Z., Pérez-Castañeda, R., Sánchez-Martínez, J. G. et al. (2019). New records of invasive mollusks Corbicula fluminea (Müller, 1774), Melanoides tuberculata (Müller, 1774) and Tarebia granifera (Lamarck, 1816) in the Vicente Guerrero reservoir, Mexico. Bioinvasions Records, 8, 640–652. https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2019.8.3.21

Mackie, G. L. & Huggins, D. G. (1983). Sphaeriacean clams of Kansas. Lawrence, Kansas: Technical Publications of the State Biological Survey of Kansas, University of Kansas.

Master, L. L., Faber-Langendoen, D., Bittman, R., Hammerson, G. A., Heidel, B., Ramsay, L. et al. (2012). NatureServe conservation status assessments: factors for evaluating species and ecosystem risk. Arlington, VA: NatureServe.

McMahon, R. F. (2002). Evolutionary and physiological adaptations of aquatic invasive animals: r selection versus resistance. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 59, 1235–1244.

Modesto, V., Ilarri, M., Souza, A. T., Lopes-Lima, M., Douda, K., Clavero, K. et al. (2017). Fish and mussels: importance of fish for freshwater mussel conservation. Fish and Fisheries, 19, 144–159. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12252

MolluscaBase, (2019). Accessed 07 Jun, 2020 from: http://www.molluscabase.org

Morelet, A. (1851). Testacea novissima insulae Cubanae et Americae Centralis, II. Baillière, Paris: Libraire de L’Académie Nationale de Médecines.

Naranjo-García, E., & Castillo-Rodríguez, Z. G. (2017). First inventory of the introduced and invasive mollusks in Mexico. Nautilus, 131, 107–126.

Paraense, W. L., & Pointier, J. P. (2003). Physa acuta Draparnaud, 1805 (Gastropoda: Physidae): a study of topotypic specimens. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz (in Rio de Janeiro), 98, 513–517.

Perez, K. E., & Minton, R. L. (2008). Practical applications for systematics and taxonomy in North American freshwater gastropod conservation. Journal of the North American Benthological Society, 27, 472–483.

Pointer, J. P. (1993). The introduction of Melanoides tuberculata (Mollusca: Thiaridae) to the island of Saint Lucia (West Indies) and its role in the decline of Biomphalaria glabrata, the snail intermediate host of Schistosoma mansoni. Acta Tropica, 54, 13–18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0001-706X(93)90064-I

Prime, T. (1852). Descriptions of two new species of fresh water shells. Annals of the Lyceum of Natural History of New York, 5, 218–219.

Prime, T. (1865). Monograph of American Corbiculadae. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, 7, 1–80.

Rosser, T. G., Alberson, N., R., Khoo, L. H., Woodyard, E. T., Wise, D. J., Pote. L. M. et al. (2016). Biomphalaria havanensis is a natural first intermediate host for the trematode Bolbophorus damnificus in commercial catfish production in Mississippi. North American Journal of Aquaculture, 78, 189–192. http://doi:10.1080/15222055.2016.1150922

Semarnat (Secretaría del Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales), (2010). Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010. Protección ambiental – Especies nativas de México de flora y fauna silvestres – Categorías de riesgo y especificaciones para su inclusión, exclusión o cambio – Lista de especies en riesgo. Diario Oficial de la Federación. 30 de diciembre de 2010, Segunda Sección, México.

Sousa, R., Antunes, C., & Guilhermino, L. (2008). Ecology of the invasive Asian claim Corbicula fluminea (Müller, 1774) in aquatic ecosystems: an overview. Annales de Limnologie – International Journal of Limnology, 44, 85–94.

Strong, E. E., Gargominy, O., Ponder, W. F., & Bouchet, P. (2008). Global diversity of gastropods (Gastropoda; Mollusca) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia, 595, 149–166.

Taylor, D. W. (1966). A remarkable snail fauna from Coahuila, Mexico. The Veliger, 9, 152–228.

Thompson, F. G. (1999). An identification manual for the freshwater snails of Florida. Walkerana, 10, 1–96.

Thompson, F. G. (2011). An annotated checklist and bibliography of the land and freshwater snails of Mexico and Central America. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History, 50, 1–299.

Vander-Zanden, M. J., & Olden, J. D. (2008). A management framework for preventing the secondary spread of aquatic invasive species. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 65, 1512–1522.

Vaughn, C. C., & Hakenkamp, C. C. (2001). The functional role of burrowing bivalves in freshwater ecosystems. Freshwater Biology, 46, 1431–1446.

Vinarski, M. V. (2018). The species question in freshwater malacology: from Linnaeus to the present day. Folia Malacologica, 26, 39–52.

Wethington, A. R, Wise, J., & Dillon, R. T. (2009). Genetic and morphological characterization of the Physidae of South Carolina (Gastropoda: Pulmonata: Basommatophora), with description of a new species. The Nautilus, 123, 282–292.