Spinitectus mixtecoensis sp. nov. (Nematoda: Cystidicolidae), from the Oaxaca killifish Profundulus punctatus (Osteichthyes: Profundulidae) from Mexico, with comments on the distribution of Spinitectus humbertoi in the genera Profundulus and Tlaloc

Juan José Barrios-Gutiérrez a, Ana Santacruz b, Emilio Martínez-Ramírez c, Miguel Rubio-Godoy d, Carlos Daniel Pinacho-Pinacho e, *

a Universidad de la Sierra Sur, Guillermo Rojas Mijangos s/n, Ciudad Universitaria, 70800 Miahuatlán de Porfirio Díaz, Oaxaca, Mexico

b Posgrado en Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Apartado Postal 70-153, Ciudad Universitaria, 04510 Ciudad de México, Mexico

c Área de Acuacultura, Centro Interdisciplinario de Investigación para el Desarrollo Integral Regional, Unidad Oaxaca, Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Hornos Núm. 1003, Col. Noche Buena, 71230 Santa Cruz Xoxocotlán, Oaxaca, Mexico

d Red de Biología Evolutiva, Instituto de Ecología, A.C., Km 2.5 Ant. Carretera a Coatepec, 91070 Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico

e Cátedras Conacyt, Red de Estudios Moleculares Avanzados, Instituto de Ecología, A.C., Km 2.5 Ant. Carretera a Coatepec, 91070 Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico

*Corresponding author: carlos.pinacho@inecol.mx (C.D. Pinacho-Pinacho)

Abstract

Spinitectus mixtecoensis sp. nov. was isolated from the intestine of Profundulus punctatus from the rivers Apoala and Los Sabinos, Oaxaca, Mexico. The new species is described based on morphological and metric analyses, scanning electron microscopy, and partial sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase 1 (cox 1) gene. Spinitectus mixtecoensis sp. nov. is characterized by possessing 7 rings and few spines per ring, between 22-28 in both sexes and 5-8 spines per sector. The new species most closely resembles Spinitectus humbertoi, a parasite of Profundulus and Tlaloc from Central America. Specimens of Spinitectus mixtecoensis sp. nov. (n = 3) and S. humbertoi (n = 2) were sequenced for the cox 1 gene, and the sequences were aligned with other nematode sequences available in GenBank. Maximum likelihood and Bayesian inference analyses indicated that this new species forms an independent, well-supported clade with high posterior probability (pp). Spinitectus mixtecoensis sp. nov. is the third species of Spinitectus recorded in profundulid fish from Central America.

Keywords:

New species; Central America; Taxonomy; Cox 1

© 2019 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. Este es un artículo Open Access bajo la licencia CC BY-NC-ND

Spinitectus mixtecoensis sp. nov. (Nematoda: Cystidicolidae), del escamudo oaxaqueño Profundulus punctatus (Osteichthyes:Profundulidae) en México, con comentarios sobre la distribución de Spinitectus humbertoi en los géneros Profundulus y Tlaloc

Resumen

Spinitectus mixtecoensis sp. nov. se aisló del intestino de Profundulus punctatus capturados en los ríos Apoala y Los Sabinos, Oaxaca, México. La especie nueva se describe con base en análisis morfológicos y métricos, microscopía electrónica de barrido y secuencias parciales del gen mitocondrial citocromo c oxidasa 1 (cox 1). Spinitectus mixtecoensis sp. nov. se caracteriza por tener 7 anillos y pocas espinas por anillo, entre 22-28 en ambos sexos y de 5-8 espinas por sector. La nueva especie se parece a Spinitectus humbertoi, parásito de Profundulus y Tlaloc en Centroamérica. Ejemplares de Spinitectus mixtecoensis sp. nov. (n = 3) y S. humbertoi (n = 2) fueron secuenciados para el gen cox 1, y las secuencias se alinearon con otras disponibles en GenBank para nemátodos. Los análisis de máxima verosimilitud e inferencia bayesiana indicaron que esta nueva especie forma un clado independiente y bien sustentado con valores de probabilidades posteriores. Spinitectus mixtecoensis sp. nov. es la tercera especie de Spinitectus registrada en peces profundúlidos de Centroamérica.

© 2019 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license

Palabras clave:

Especies nuevas; Centroamérica; Taxonomía; Cox 1

Introduction

The genus Spinitectus Fourment, 1883 includes a large number of species infecting freshwater and marine fishes, some amphibians, and one species is known from a mammal (Boomker, 1993; Moravec et al., 2002, 2009, 2010). Sixteen species of Spinitectus have been reported from freshwater fishes in the New World (Spinitectus acipenseri Choudhury and Dick, 1992; S. agonostomi Moravec and Baruš, 1971; S. asperus Travassos, Artigas and Pereira, 1928; S. carolini Holl, 1928; S. gracilis Ward and Magath, 1917; S. humbertoi Caspeta-Mandujano and Moravec, 2000; S. mariaisabelae Caspeta-Mandujano, Cabañas-Carranza and Salgado-Maldonado, 2007; S. mexicanus Caspeta-Mandujano, Moravec and Salgado-Maldonado, 2000; S. micracanthus Christian, 1972; S. multipapillatus Petter, 1987; S. osorioi Choudhury and Pérez-Ponce de León, 2001; S. pachyuri Petter, 1984; S. rodolphiheringi Vaz and Pereira, 1934; S. tabascoensis Moravec, Salgado-Maldonado, Caspeta-Mandujano and González-Solís, 2009; S. yorkei Travassos, Artigas and Pereira, 1928 and S. aguapeiensis Acosta, González-Solís and da Silva, 2017 (Moravec, 1998; Caspeta-Mandujano et al., 2007; Moravec et al., 2009, 2010; Caspeta-Mandujano, 2010; Acosta et al., 2017). Of those, 6 species have been reported from Mexico: S. agonostomi, S. humbertoi, S. mariaisabelae, S. mexicanus, S. osorioi, and S. tabascoensis (Caspeta-Mandujano, 2010). Spinitectus humbertoi and S. mariaisabelae represent the core helminth fauna of profundulid fishes in Middle America and are not shared with other fish species (Pinacho-Pinacho et al., 2015).

In the freshwater fish family Profundulidae distributed in Central America, Profundulus Hubbs, 1924 is the most species-rich genus, containing 6 valid species, and Tlaloc (Morcillo, Ornelas-García, Alcatraz, Matamoros and Doadrio, 2016) contains 4 species (Jamangapé et al., 2016; Morcillo et al., 2016; Ornelas-García et al., 2015). The helminth fauna of Profundulus and Tlaloc consists in digenea, monogenea, cestodea, and nematoda (García-Vásquez et al., 2018; Pinacho-Pinacho et al., 2015). During a study of helminth parasites of freshwater fish from the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Biosphere Reserve in Oaxaca, Mexico (Barrios-Gutiérrez et al., 2018), we found nematodes of a new species of Spinitectus in the intestine of Profundulus punctatus Günther, 1866. Parasites were subjected to morphological and metric analyses, observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and characterized molecularly.

Materials and methods

Fifty-four specimens of P. punctatus were collected in the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Biosphere Reserve, Oaxaca, Mexico in October-November 2015. Seven localities were sampled: 1) Manantial de Santa María Ixcatlán (17°51’4.7” N, 97°11’57.5” W); 2) Río El Sabino, Santa María Ixcatlán (17°50’11.4” N, 97°10’46.5” W); 3) Río Los Sabinos, San Pedro Nodón, Santa María Ixcatlán (17°47’59.1” N, 97°8’11.3” W); 4) Río Los Sabinos, San Miguel Huautla (17°44’28.9” N, 97°8’17.8” W); 5) Río Apoala, Santiago Apoala (17°38’57.2” N, 97°8’12.1” W); 6) Puente de la entrada a Santa María Texcatitlán (17°42’44.3” N, 97°3’9” W), and 7) Río de Santa Catarina Tlaxila, San Juan Bautista Cuicatlán (17°33’38.3” N, 96°51’11.3” W). Fish were captured by electrofishing, transported alive to the laboratory and studied for helminths a few hours after their capture; individual hosts were killed by spinal severance (pithing) following AVMA (2013) guidelines and all internal organs were examined for parasites under a dissecting microscope. Nematodes isolated from the intestine were fixed in hot 4% formaldehyde and cleared with glycerin (Caspeta-Mandujano, 2010).

Illustrations of the specimens were made with the aid of a drawing tube. Specimens were examined using a bright field Leica DM 1000 LED microscope and the measurements were acquired using the Leica Application Suite microscope software, and are presented in millimeters (mm), with the range followed by the mean values in parentheses. After examination, the specimens were stored in 70% ethanol. For SEM observations, 5 specimens of the new species and 2 specimens of S. humbertoi were dehydrated through an ethanol series, critical point dried, sputter-coated with gold and examined at 15 kV in a Hitachi Stereoscan Model SU1510 SEM (Hitachi Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at the Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). The holotype, allotype and paratypes were deposited in the Colección Nacional de Helmintos (CNHE), Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. For morphological comparisons, type-specimens of the following species were examined: S. humbertoi (CNHE 4028, 4030) and S. mariaisabelae (CNHE 5781, 5782, 5783). Voucher specimens of S. humbertoi (CNHE 9443, 9639, 9638) were also examined.

DNA extraction was obtained from individual nematodes, preserving anterior and posterior ends of the worms as vouchers (hologenophore) from 3 individual nematodes of the new species and 2 of S. humbertoi. The samples were digested overnight at 56 °C in a solution containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH = 7.6), 20 mM NaCl, 100 mM Na2 EDTA (pH = 8.0), 1% Sarkosyl and 0.1 mg/ml proteinase K. Following digestion, DNA was isolated from the supernatant using the DNAzol reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A partial fragment of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox 1) gene was amplified with the forward primer (507) 5′-AGTTCTAATCATAA(R)GATAT(Y)GG and the reverse primer (HCO2198) 5′- TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA (Folmer et al., 1994; Nadler et al., 2006). PCR reactions (25 μl) consisted of 10 mM of each primer, 2.5 μl of buffer 10×, 50 mM MgCl2, 0. 5 μl of dNTPS mixture (10mM), 0.125 μl of Taq DNA polymerase (1 U/μl) (Vivantis Technologies Sdn Bhd, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia) and 2 μl of DNA. Thermocycling conditions included denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, annealing at 48 °C for 1 min, and extension at 72 °C for 2 min, followed by a post-amplification incubation at 72 °C for 7 min. PCR amplicons were enzymatically purified with ExoSAP-IT (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and sequenced in both directions; sequencing reactions were performed using ABI Big Dye (Applied Biosystems, Boston, Massachusetts) terminator sequencing chemistry, and reaction products were separated and detected using an ABI 3730 capillary DNA sequencer. Contiguous sequences were assembled, and base-calling differences resolved using Codoncode Aligner version 5.0.2 (Codoncode Corporation, Dedham, Massachusetts) and submitted to GenBank.

Partial sequences obtained from the cox 1 gene were aligned with sequences of Spirocerca sp. (KJ605484, KJ605487); Onchocerca dewittei Bain, Ramachandran, Petter and Mak, 1977 (AB518689, AB518690); Onchocerca skrjabini Rukhlyadev, 1964 (AM749269, AM749270); Dirofilaria repens Railliet and Henry, 1911 (AM749232, AM749234); Gongylonema pulchrum Molin, 1857 (LC026041); Rhabdochona lichtenfelsi Sánchez-Alvarez, García-Prieto and Pérez-Ponce de León, 1998 (DQ990982, DQ990974) and Rhabdochona mexicana Caspeta-Mandujano, Moravec and Salgado-Maldonado, 2000 (DQ991010) available in the GenBank database, using ClustalW with default parameters implemented in MEGA version 7.0 (Kumar et al., 2016). Sequences were trimmed after final alignment. The best-fitting nucleotide substitution models (cox 1: GTR+G) were estimated with the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) implemented in MEGA version 7.0 (Kumar et al., 2016). Phylogenetic trees were reconstructed by maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) analyses. For ML analyses, the program RAxML v7.0.4 (Stamatakis, 2006) was used. A GTRGAMMAI substitution model was used for ML analyses, and 10,000 bootstrap replicates were run to assess nodal support. The phylogenetic analyses were run under Bayesian inference (BI) criteria, employing the nucleotide substitution model identified for AIC. BI trees were generated using MrBayes v3.2 (Ronquist et al., 2012), running 2 independent MC3 runs of 4 chains for 5 million generations and sampling tree topologies every 1,000 generations. ‘Burn-in’ periods were set to 1 million of generations according to the standard deviation of split frequencies values (˂ 0.01). Posterior probabilities of clades were obtained from 50% majority rule consensus of sample trees after excluding the initial 20% as ‘burn-in’. The numbers of variable sites in the sequences of the new species and the genetic divergence among species of Spinitectus were estimated using uncorrected “p” distances with the program MEGA version 7.0 (Kumar et al., 2016).

Description

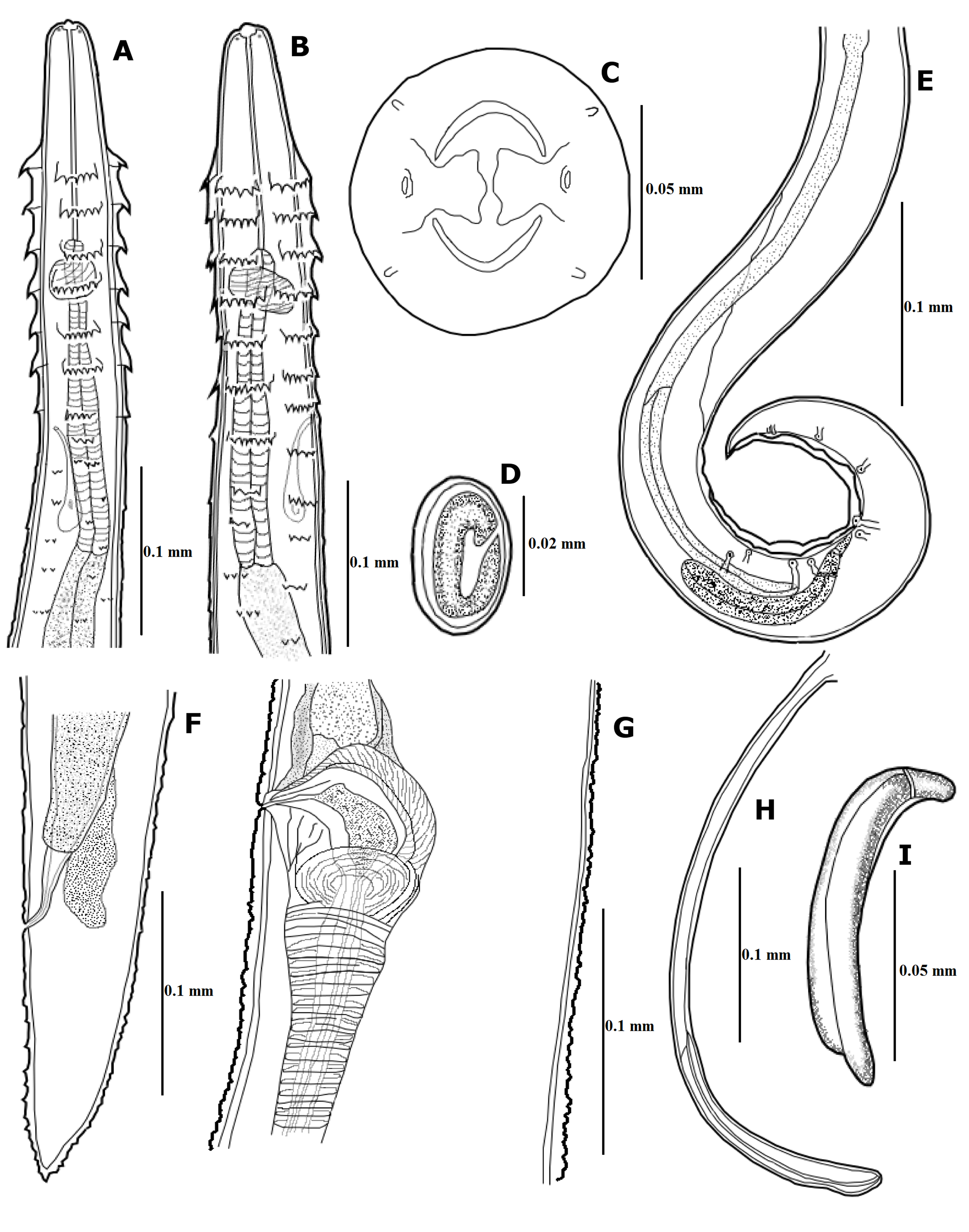

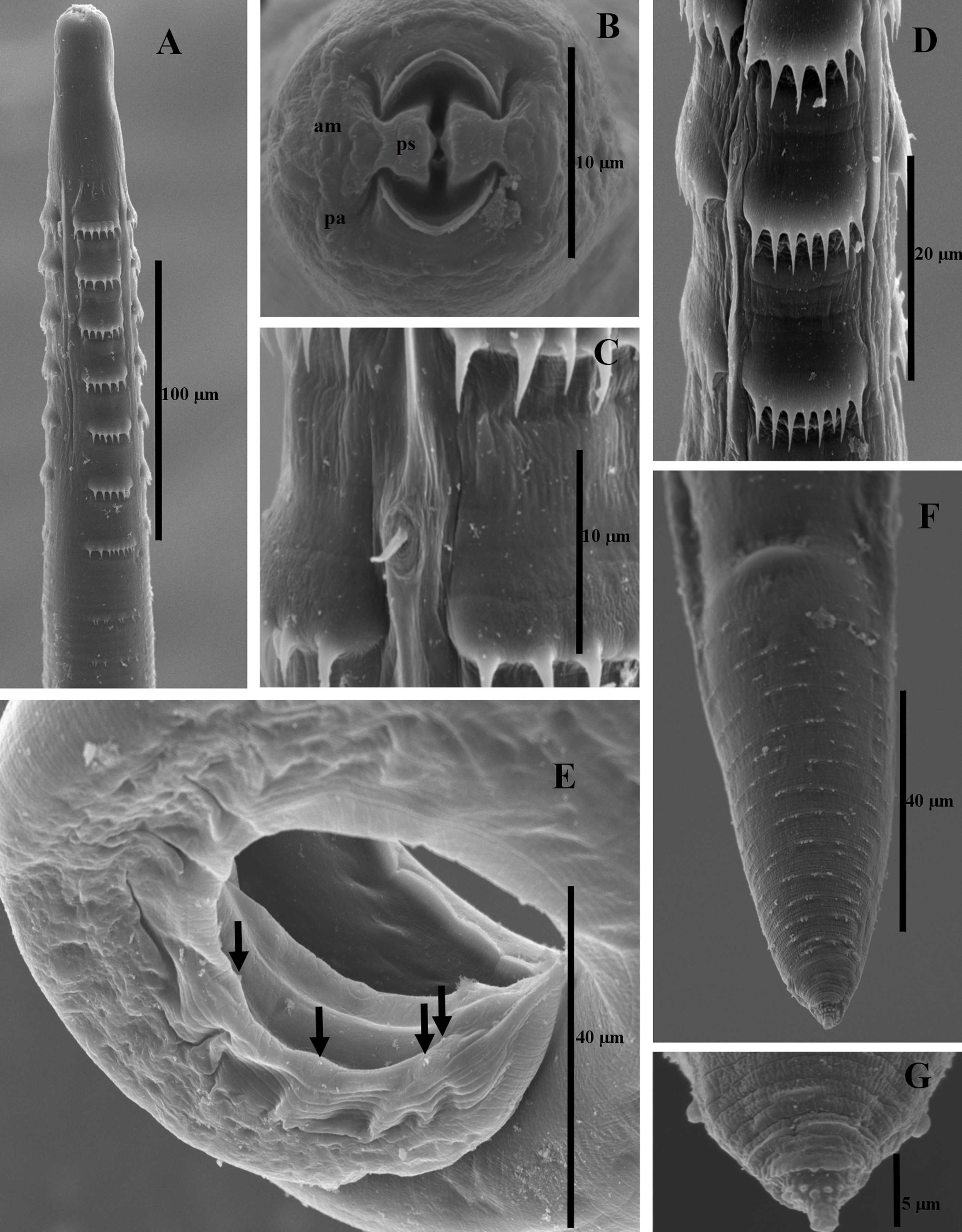

Spinitectus mixtecoensis sp. nov. (Figs. 1A-I, 2A-G)

Family Cystidicolidae Skrjabin, 1946

General: medium sized nematodes with rather thick cuticle bearing rings of spines, these being divided at anterior end of body into 4 distinctly-separated dorsolateral and ventrolateral sectors (Figs. 1A, B; 2A, D). First ring usually somewhat anterior to or at level of end of vestibule (stoma) (Figs. 1A, B; 2A). Seven anterior rings of well-developed spines, first 6 rings with 5 to 8 spines of similar size; ring number 7 with 9 spines, but of smaller size; rings are more or less regularly spaced (Fig. 2A, D). First ring of spines consisting of 22 spines in males (5-7 per sector) and 28 spines in females (6-8 per sector) (Figs. 1A, B; 2A, D). Small and simple deirids situated between first and second ring of spines (Fig. 2C). Cephalic end rounded, mouth encircled by 2 pseudolabia, 4 papillae and 2 amphids (Figs. 1C; 2B). Vestibule rather long, its anterior end dilated to form funnel shaped prostom. Excretory pore just posterior to the seventh ring of spines (Fig. 1A, B).

Male (based on 11 specimens). Body length 3.29-4.49 (3.79), maximum width 0.06-0.12 (0.08). Length of vestibule, muscular oesophagus and glandular oesophagus 0.10-0.12 (0.11), 0.15-0.19 (0.17) and 0.46-0.68 (0.54), respectively. Length ratio of muscular to glandular oesophagus 1:2.61-3.71 (3.17). Distance from anterior extremity: first ring of spines 0.07-0.08 (0.08), deirids 0.09-0.10 (0.09), and nerve ring 0.12-0.14 (0.13). Posterior end of body spirally coiled, with caudal alae. Caudal papillae: 4 pairs of preanal papillae and 6 pairs of postanal papillae arranged in 4 groups, 2 groups of 2 pairs and 2 groups of 1 pair (Figs. 1E; 2E). Rugged area well developed, formed by a few longitudinal cuticular ridges. Larger (left) spicule slender, 0.34-0.42 (0.38) mm long, with distal end; length of its shaft 0.19-0.25 (0.22), representing 56.73-63.56 % (57.22%) of spicule length (Fig. 1H). Small (right) spicule longer than wide, 0.07-0.09 (0.08) long (Fig. 1I). Length ratio of spicules 1:4.14-5.35 (1:3.72). Tail conical, 0.11-0.13 (0.12) long (Fig. 1E).

Female (based on 11 gravid specimens): length 3.91-5.80 (4.84), maximum width 0.09-0.16 (0.12). Length of vestibule, muscular oesophagus and glandular oesophagus 0.10-0.12 (0.11), 0.17-0.22 (0.19) and 0.56-0.85 (0.66), respectively. Length ratio of muscular to glandular oesophagus 1:2.94-3.86 (1:3.87). Distance from anterior extremity: first ring of spines 0.08-0.10 (0.09), deirids 0.10-0.11 (0.10), nerve ring 0.14-0.16 (0.15). Vulva pre-equatorial, situated 1.62-2.38 (2.04) from anterior extremity (Fig. 1G). Fully mature eggs oval, smooth, larvated; size of eggs 0.03-0.03 × 0.01 (0.03 × 0.01) (Fig. 1D). Tail conical, bearing small spines irregularly spaced 0.11-0.16 (0.13) (0.12) long. Tail tip bearing small spike-like processes; a pair of small papillae (phasmids) present laterally not far from the distal end (Figs. 1F, 2F, G).

Taxonomic summary

Type host: Profundulus punctatus (Günther) (Osteichthyes:Profundulidae).

Site of infection: intestine.

Type locality: Río Apoala, Santiago Apoala, Oaxaca, México (17°38’57.2” N, 97°8’12.1” W).

Additional locality: Río Los Sabinos, San Pedro Nodón, Santa María Ixcatlán, Oaxaca, México (17°47’59.1” N, 97°8’11.3” W).

Infection parameters: Río Apoala: prevalence 60%, abundance 11.8 ± 11.1, and mean intensity 19.67 ± 3.21. Río Los Sabinos: prevalence 10%, abundance 0.7 ± 2.21, and mean intensity 7.

Deposition of types: holotype, allotype and paratypes in Colección Nacional de Helmintos, CNHE, Institute of Biology, UNAM, Mexico (CNHE 10909, 10910, 10911, respectively).

Sequences: sequences obtained from 3 specimens of the new species and 2 sequences from S. humbertoi were deposited in GenBank (accession Nos. MK024431-MK024435).

Remarks

Spinitectus mixtecoensis sp. nov. presents all the characteristics of the genus Spinitectus according to Moravec (1998), such as a cuticle provided with transverse rows of spines, 2 pseudolabia, a relatively long vestibule and caudal alae supported by pedunculate papillae. To date, 6 congeneric species of Spinitectus have been recorded from Mexico (Caspeta-Mandujano, 2010): S. agonostomi from Agonostomus monticola (Bancroft), S. humbertoi from Profundulus labialis (Günther), S. mariaisabelae from Profundulus punctatus (Günther), S. mexicanus from Pseudoxiphophorus bimaculatus (Heckel), S. osorioi from Chirostoma attenuatum (Meek) and C. estor (Jordan), and S. tabascoensis from Ictalurus furcatus (Valenciennes). Of these, S. humbertoi and S. mariaisabelae were described from the same host as the new species described here, Profundulus punctatus. Spinitectus mariaisabelae differs from S. mixtecoensis sp. nov. in having smaller body length (males: 6.56-8.28 mm vs. 3.29-4.49 mm; females: 11.82-14.58 mm vs. 3.91-5.80 mm), higher number of rings (8 vs. 7), and higher number of spines per row and sector [males: 52-60 (13-15 per sector) vs. 22-28 (5-8 per sector); females: 64-72 vs. 22-28 (5-8 per sector)]. Spinitectus humbertoi is more similar to the new species, but can likewise be distinguished for its longer body (males: 2.96-3.20 mm vs. 3.29-4.49 mm; females: 3.67-4.29 mm vs. 3.91-5.80 mm), higher number of rings (8 vs. 7), and higher number of spines per row and sector (males and females: 36-38 (8-10 per sector) vs. 22-28 (5-8 per sector)).

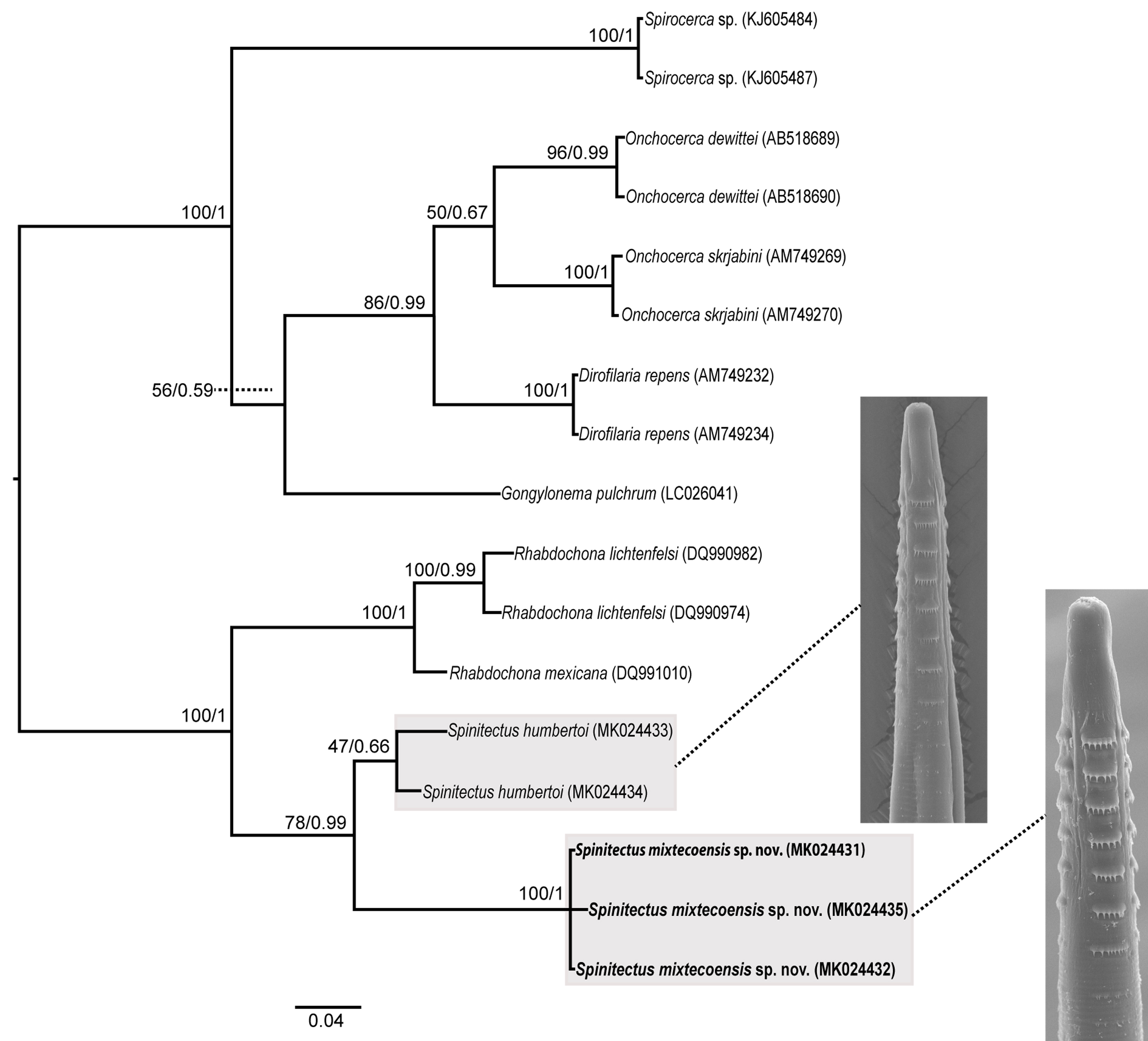

Partial sequences of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox 1) gene were obtained from 3 specimens of S. mixtecoensis sp. nov. and from 2 specimens of S. humbertoi. Phylogenetic analyses of the cox 1 dataset (441 bp long) included 3 haplotypes of S. mixtecoensis sp. nov., 2 haplotypes of S. humbertoi and 12 sequences retrieved from GenBank, including Spirocerca sp., Onchocerca spp., Dirofilaria repens, Gongylonema pulchrum and Rhabdochona spp. Phylogenetic analyses yielded trees with similar topologies among the analyzed species, all with well-supported nodes. The ML analysis resulted in one tree (not shown) with a value of likelihood = -1746.931856. Spinitectus mixtecoensis sp. nov. was found to be reciprocally monophyletic in all analyses, with strong nodal support of bootstrap and posterior probabilities values (100/1). Haplotypes of S. mixtecoensis sp. nov. and S. humbertoi, both found in Profundulus fishes formed a clade with very high branch support (78/0.99 of bootstrap/pp) (Fig. 3). Genetic divergence among the new species and S. humbertoi ranged from 6.6 to 7.5%. Values of nucleotide intra-specific variation in S. mixtecoensis sp. nov. and S. humbertoi were of 0 to 0.6% and 0 to 2.5%, respectively.

Discussion

In this study, we describe 1 new species of Spinitectus, thus contributing to the characterization of the helminth fauna of Profundulidae, a freshwater fish family endemic to Middle America (Morcillo et al., 2016). Currently, the helminth fauna of Profundulidae consists of 11 trematodes, 4 monogeneans, 1 adult cestode and 6 nematodes (García-Vásquez et al., 2018; Pinacho-Pinacho et al., 2015). Two species of Spinitectus are known from Profundulus, S. humbertoi and S. mariaisabelae (Caspeta-Mandujano & Moravec, 2000; Caspeta-Mandujano et al., 2007); Spinitectus mixtecoensis sp. nov. represents the third species recorded in profundulids from Mexico.

Freshwater fishes from the genera Profundulus and Tlaloc inhabit environments with sandy substrate, silt, mud, gravel, rocks and boulders; and have an omnivorous habit, consuming mainly arthropods, clams, snails, free-living nematodes, algae and debris. Both genera probably get infected with helminths when feeding on arthropods (Miller, 2005). Species of Spinitectus normally use arthropods as intermediate hosts and fish may act as paratenic hosts (Anderson, 2000). Members of the genera Profundulus and Tlaloc can be considered definitive hosts for Spinitectus spp.

Spinitectus mixtecoensis sp. nov. is easy to distinguish from the other 2 species parasitizing Profundulus fishes: it has a smaller number of rings of spines and a different number of spines per ring and sector (see Remarks section). Compared with other species of Spinitectus recorded in North and Central America, the new species can be differentiated by having smaller body length, i.e., S. micracanthus (males: 7.6-8.2 mm), S. gracilis (males: 8-10; females: 10-15 mm), S. beaveri (males: 4.83-6.04; females: 5.85-7.04 mm), S. macrospinosus (males: 5.50-8.00; females: 8.70-12.65 mm), S. tabascoensis (males: 9.49-11.98; females: 14.39-15.74 mm) (Choudhury & Perryman, 2003; Frederick, 1972; Moravec et al., 2009; Overstreet, 1970). Spinitectus agonostomi, S. mexicanus, S. osorioi, and S. acipenseri possess different arrangements in the rings and different number of spines per ring (Caspeta-Mandujano et al., 2000; Choudhury & Dick, 1992; Choudhury & Pérez-Ponce de León, 2001).

In South America, 5 species of Spinitectus have been described; i.e., S. asperus, S. multipapillatus, S. pachyuri, S. rodolphiheringi, and S. yorkei (Moravec, 1998; Petter, 1984, 1987; Travassos et al., 1928; Vaz & Pereira, 1934). Spinitectus asperus and S. rodolphiheringi differ from S. mixtecoensis sp. nov. in having a higher number of spines per row (60-90 and 30-40, respectively vs. 22-28). However, Moravec (1998) considers that the species S. multipapillatus and S. yorkei could be the conspecific due to their inadequate description. Recently, Acosta et al. (2017) described a fourth species of Spinitectus from Pimelodella spp. and the sixth species in South America.

Maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) analyses for the partial sequences of the cox 1 gene show that Spinitectus mixtecoensis sp. nov. represents an independent clade, possessing a high nodal support and exhibiting high genetic divergence values in comparison with S. humbertoi (p distance from 6.6 to 7.5%); these are the first sequences reported for the cox 1 gene for both the new species and S. humbertoi. The species S. humbertoi is the most widely distributed of the known parasites of Profundulus and Tlaloc from Central America.

Pinacho- Pinacho et al. (2015) reported this species in 20 localities from Profundulus balsanus Ahl, 1935; P. punctatus (Günter, 1866); P. guatemalensis (Günter, 1866); P. kreiseri Matamoros, Schaefer, Hernández and Chakrabarty, 2012; P. candalarius Hubbs, 1924; Tlaloc labialis (Günter, 1866), and T. portillorum Matamoros and Schaefer, 2010. The same authors recently published a checklist of the helminth parasites of Profundulidae from Mesoamerica; however, they did not find specimens of S. mariaisabelae (Pinacho-Pinacho et al., 2015). In that previous work, specimens of S. humbertoi were sequenced from 2 localities separated by a distance of approximately 800 km: Río Santa María Huatulco (15°50’14.2″ N, 96°19’30.8″ W) in Mexico, and Puente Sansare (14°44’52” N, 90°06’33” W) in Guatemala, and parasite specimens from these populations showed values of intra-specific nucleotide variation of 2.5%.

The description of the biodiversity of Spinitectus of Mexico is fundamental for future studies and will contribute to a better understanding of the historical biogeography, evolutionary history, and host-parasite associations of this particular group. Pérez-Ponce de León and Choudhury (2010) suggest that molecular data are fundamental to better understand the biodiversity patterns of groups of parasites, and stress that these are also important for establishing relationships between species described already and those new to science. The integrative taxonomy data that we generated in this study will hopefully contribute to the knowledge on the evolution and biogeography of Spinitectus infecting freshwater fishes from Central America.

Acknowledgments

To Eufemia Cruz Arenas and her work group from CIDIIR-Oaxaca, for helping during field work. To Martín García Varela and Gerardo Pérez Ponce de León, for the space, materials and all facilities provided in their laboratories; Luis García Prieto, for the loan of specimens from the Colección Nacional de Helmintos (México City) and his help in the deposition of types in the same collection; Berenit Mendoza Garfias for the technical assistance with the SEM; and to David Osorio Sarabia for his help in the observation of specimens —all of the latter from Instituto de Biología, UNAM.

References

Acosta, A. A., González-Solís, D., & Da Silva, R. J. (2017). Spinitectus aguapeiensis n. sp. (Nematoda: Cystidicolidae) from Pimelodella avanhandavae Eigenmann (Siluriformes: Heptapteridae) in the River Aguapeí, Upper Paraná River Basin, Brazil. Systematic Parasitology, 94, 649–656.

Anderson, R. C. (2000). Nematode parasites of vertebrates: their development and transmission. New York: CABI Publishing.

AVMA (American Veterinary Medical Association). (2013). Guidelines for the euthanasia of animals, 2013 edition. Schaumburg, Illinois: American Veterinary Medical Association.

Barrios-Gutiérrez, J. J., Martínez-Ramírez, E., Gómez-Ugalde, R. M., García-Varela, M., & Pinacho-Pinacho, C. D. (2018). Helmintos parásitos de los peces dulceacuícolas de la Reserva de la Biosfera Tehuacán-Cuicatlán, región Oaxaca. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 89, 29–38.

Boomker, J. (1993). Parasites of South African freshwater fish. V. Description of two new species of the genus Spinitectus Fourment, 1883 (Nematoda: Cystidicolidae). Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research, 60, 139–145.

Caspeta-Mandujano, J. M. (2010). Nematodos parásitos de peces de agua dulce de México. México D.F.: AGT.

Caspeta-Mandujano, J. M., Cabañas-Carranza, G., & Salgado-Maldonado, G. (2007). Spinitectus mariaisabelae n. sp. (Nematoda: Cystidicolidae) from the intestine of the freshwater fish Profundulus punctatus (Cyprinodontiformes) in Mexico. Helminthologia, 44, 103–106.

Caspeta-Mandujano, J. M., & Moravec, F. (2000). Two new intestinal nematodes of Profundulus labialis (Pisces, Cyprinodontidae) from freshwaters in Mexico. Acta Parasitologica, 45, 332–339.

Caspeta-Mandujano, J. M., Moravec, F., & Salgado-Maldonado, G. (2000). Spinitectus mexicanus n. sp. (Nematoda: Cystidicolidae) from the intestine of the freshwater fish Heterandria bimaculata in Mexico. Journal of Parasitology, 86, 83–88.

Choudhury, A., & Dick T. A. (1992). Spinitectus acipenseri n. sp. (Nematoda: Cystidicolidae) from the lake sturgeon Acipenser fulvescens (Rafinesque) in Canada. Systematic Parasitology, 22, 131–140.

Choudhury, A., & Pérez-Ponce de León, G. (2001). Spinitectus osorioi n. sp. (Nematoda: Cystidicolidae) from Chirostoma spp. (Osteichthyes: Atherinidae) in Lake Pátzcuaro, Michoacán, México. Journal of Parasitology, 87, 648–655.

Choudhury, A., & Perryman, B. J. (2003). Spinitectus macrospinosus n. sp. (Nematoda: Cystidicolidae) from the channel catfish Ictalurus punctatus in southern Manitoba and its distribution in other Ictalurus spp. Journal of Parasitology, 89, 782–791.

Folmer, O., Black, M., Hoeh, W., Lutz, R., &Vrijenhoek, R. (1994). DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Molecular Marine Biology and Biotechnology, 3, 294–299.

Frederick, A. C. (1972). Spinitectus micracanthus sp. n. (Nematoda: Rhabdochonidae) from the Bluegill, Lepomis macrochirus Rafinesque, in Ohio. The Helminthological Society of Washington, 39, 51–54.

García-Vásquez, A., Pinacho-Pinacho, C. D., Martínez-Ramírez, E., & Rubio-Godoy, M. (2018). Two new species of Gyrodactylus von Nordmann, 1832 from Profundulus oaxacae (Pisces: Profundulidae) from Oaxaca, Mexico, studied by morphology and molecular analyses. Parasitology International, 67, 517–527.

Jamangapé, O. J. A., Velázquez-Velázquez, E., Martínez-Ramírez, E., Anzueto-Calvo, M. J., Gómez, E. L., Domínguez-Cisneros, S. E. et al. (2016). Validity and Redescription of Profundulus balsanus Ahl, 1935 (Cyprinodontiformes: Profundulidae). Zootaxa, 4173, 55–65.

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., & Tamura, K. (2016). MEGA 7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 33, 1870–1874.

Miller, R. R. (2005). Freshwater fishes of Mexico. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Moravec, F. (1998). Nematodes of freshwater fishes of the Neotropical Region. Praha: Academia.

Moravec, F., García-Magaña, L., & Salgado-Maldonado, G. (2002). Spinitectus tabascoensis sp. nov. (Nematoda, Cystidicolidae) from Ictalurus furcatus (Pisces) in southeastern Mexico. Acta Parasitologica, 47, 224–227.

Moravec, F., Salgado-Maldonado, G., & Caspeta-Mandujano, J. M. (2010). Spinitectus osorioi (Nematoda: Cystidicolidae) in the Mexican endemic fish Atherinella alvarezi (Atherinopsidae) from the Atlantic river drainage system in Chiapas, southern Mexico. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, 105, 52–56.

Moravec, F., Salgado-Maldonado, G., Caspeta-Mandujano, J. M., & González-Solís, D. (2009). Redescription of Spinitectus tabascoensis (Nematoda: Cystidicolidae) from fishes of the Lacandon rain forest in Chiapas, southern Mexico, with remarks on Spinitectus macrospinosus and S. osorioi. Folia Parasitologica, 56, 305–312.

Morcillo, F., Ornelas-García, C. P., Alcaraz, L., Matamoros, W. A., & Doadrio, I. (2016). Phylogenetic relationships and evolutionary endemic freshwater fish family Profundulidae (Cyprinodontiformes: Actinopterygii). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 94, 242–251.

Nadler, S. A., Bolotin, E., & Stock, S. P. (2006). Phylogenetic relationships of Steinernema Travassos, 1927 (Nematoda: Cephalobina: Steinernematidae) based on nuclear, mitochondrial and morphological data. Systematic Parasitology, 63, 159–179.

Ornelas-García, C. P., Martínez-Ramírez, E., & Doadrio-Villarejo, I. (2015). A new species of killifish of the family Profundulidae from the highlands of the Mixteca region, Mexico. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 86, 926–933.

Overstreet, R. M. (1970). Spinitectus beaveri sp. n. (Nematoda: Spiruroidea) from the Bonefish, Albula vulpes (Linnaeus), in Florida. Journal of Parasitology, 56, 128–130.

Pérez-Ponce de León, G., & Choudhury, A. (2010). Parasite inventories and DNA-based taxonomy: lessons from helminths of freshwater fishes in a megadiverse country. Journal of Parasitology, 96, 236–244.

Petter, A. J. (1984). Nematodes de poissons du Paraguay II. Habronematoidea (Spirurida) description de 4 espéces nouvelles de la famille des Cystidicolidae. Revue Suisse de Zoologie, 9, 935–952.

Petter, A. J. (1987). Nematodes des poissons de l’Equateur. Revue Suisse de Zoologie, 94, 61–76.

Pinacho-Pinacho, C. D., García-Varela, M., Hernández-Ortis, J., Mendoza-Palmero, C. A., Sereno-Uribe, A. L., Martínez-Ramírez, E. et al. (2015). Checklist of the helminth parasites of the genus Profundulus Hubbs, 1924 (Cyprinodontiformes, Profundulidae), an endemic family of freshwater fishes in Middle-America. Zookeys, 523, 1–30.

Ronquist, F., Teslenko, M., Van der Mark, P., Ayres, D., Darling, A., Höhna, S. et al. (2012). MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Systematic Biology, 61, 539–542.

Stamatakis, A. (2006). RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics, 22, 2688–2690.

Travassos, L., Artigas, P., & Pereira, C. (1928). Fauna helminthologica dos peixes de água doce do Brasil. Arquivos do Instituto Biológico de São Paulo, 1, 5–68

Vaz, Z., & Pereira, C. (1934). Contribuicão ao conhecimento dos nematóides de peixes fluviais do Brasil. Arquivos do Instituto Biológico de São Paulo, 5, 87–103.